A Year of Two Halves

By gofb-adm on Saturday, August 20th, 2022 in Issue 2 - 2022, Cover Story No Comments

By gofb-adm on Saturday, August 20th, 2022 in Issue 2 - 2022, Cover Story No Comments

When China’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, H.E. Wang Yi, paid an official visit to Malaysia in July 2022, he gave the assurance that his country would buy more palm oil. It was welcome news, given the significant drop in China’s imports over the first half (1H) of 2022.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, May 1st, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Cover Story No Comments

Like many other commodities, palm oil experienced high prices throughout 2021. Prices more than doubled over the past 18 months to a record high of US$1,213.85 a tonne in October 2021. In November and December, however, prices dipped and weighed on 2021’s average pricing to US$1,000 per tonne.

The high prices can be arguably attributed to lower palm oil output. For most of 2020 and throughout 2021, Covid-19 pandemic-led border closures had starved Malaysia’s oil palm estates of many foreign workers who had returned home and could not re-enter the country.

The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) also sees structural changes in the global palm oil supply due to a slowdown in new plantings throughout Indonesia and Malaysia since 2015. With the ageing tree profile across both countries, the replanting programme will also temporarily limit palm oil supply in the short to medium term.

As agricultural land becomes limited, oil palm replanting is key to boosting palm oil yield across Indonesia and Malaysia. It is important to replant to sustain supply because these countries produce about 85% of the world’s palm oil needs. LMC International highlights that the global palm oil supply will only see minimal growth in the 2019-22 period due to year-end floods and the labour shortage in Malaysia.

On the other side of the globe, severe drought at Canada’s farmlands in 2021 resulted in its smallest rapeseed harvest in 13 years. The lower-than-expected supply of soft oils induced the sharp rise in other vegetable oil prices to a 10-year high, which then had a spillover effect onto palm oil pricing. The limited supply of vegetable oils all over the world is likely to continue into the first half of this year.

Production outlook

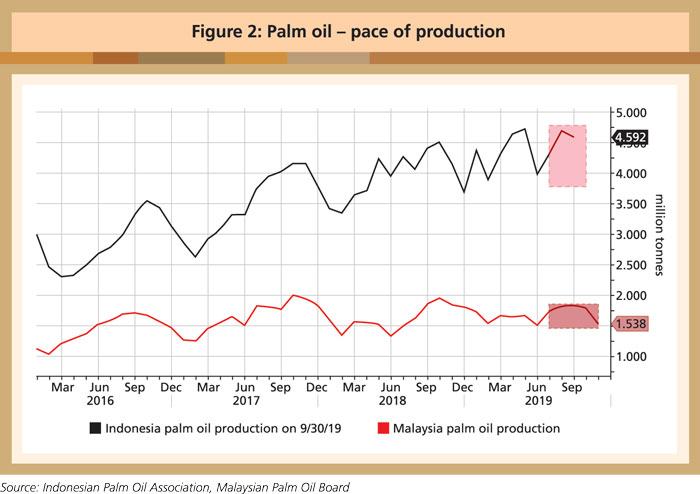

Palm oil production in Indonesia was 6.7% higher in the second quarter of 2021, gathering pace from the 1.5% growth in the first quarter and spurred by better rainfall in 2020. Output in the third quarter of 2021, however, was slightly curbed by floods in Kalimantan, which disrupted oil palm fruit harvesting. In the fourth quarter, the Indonesian Palm Oil Association (GAPKI) announced that production had fallen further. Its initial forecast of a better harvest in the second half of 2021 than the first, did not materialise. So, for the full year, GAPKI has revised its palm oil output forecast to 46.6 million tonnes, down 0.9% from 2020.

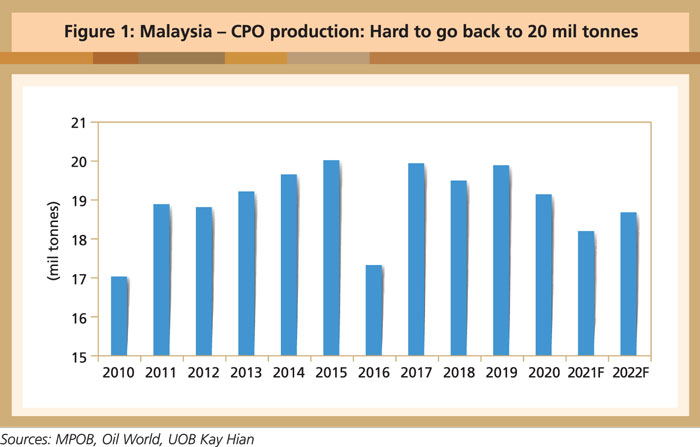

The Malaysian Palm Oil Board estimates that Malaysia’s 2021 palm oil output will drop to 18.3 million tonnes from 19.2 million tonnes in 2020. Palm oil ending stocks are expected to stay at below-average levels of 4 million tonnes in Indonesia and 2.1 million tonnes in Malaysia.

This year, Indonesian palm oil output is expected to recover due to good estate management and no halt of operations, supported by the absence of a La Nina impact. This, however, is not the case for Malaysia. Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, foreign workers who account for about 75% of the 500,000 harvesters employed on Malaysian oil palm estates have not been able to return due to border restrictions. Analysts forecast that Malaysia’s plan to bring in 32,000 foreign workers will only likely materialise towards March. The signing in December 2021 of a five-year memorandum of understanding between the governments of Malaysia and Bangladesh to hire more workers is a step in the right direction.

The second challenge is the high cost of fertiliser. Small farmers are expected to reduce fertiliser applications due to sharply increased prices, potentially reducing future output. Fertiliser and pesticide prices have surged significantly due to supply chain disruptions, higher demand, rising freight charges and input costs. The price of fertilisers, such as nitrogen and phosphate, has risen by 50-80% since mid-2021, while the price of herbicides, such as glyphosate and glufosinate, has more than doubled due to supply chain disruptions and more expensive raw materials.

It is also becoming difficult to obtain supplies. Thus, the oil palm sector may again suffer from low fertiliser applications this year. The cost of fertiliser is a major component after labour for oil palm growers, making up about 30-35% of the ex-mill costs. Companies will continue to feed oil palm trees this nutrient despite the high price, but may not receive the volume ordered due to supply constraints and uncertain shipment arrangements. Planters are highly dependent on imported fertilisers, but those in Indonesia have an advantage as local urea production is sufficient to meet domestic demand.

Based on industry sources, the estimated fertiliser imports for 2021 are 60-65% of the usual annual requirements. As the logistics bottleneck is unlikely to ease any time soon, 2022 could see even lower fertiliser imports. Smallholders may again be tempted to give less fertiliser to trees. The impact of reduced fertiliser usage in 2018 and 2019 still shows today, as yield recovery is weaker than normal. As a result, Indonesia and Malaysia may not be able to deliver much output growth in 2022.

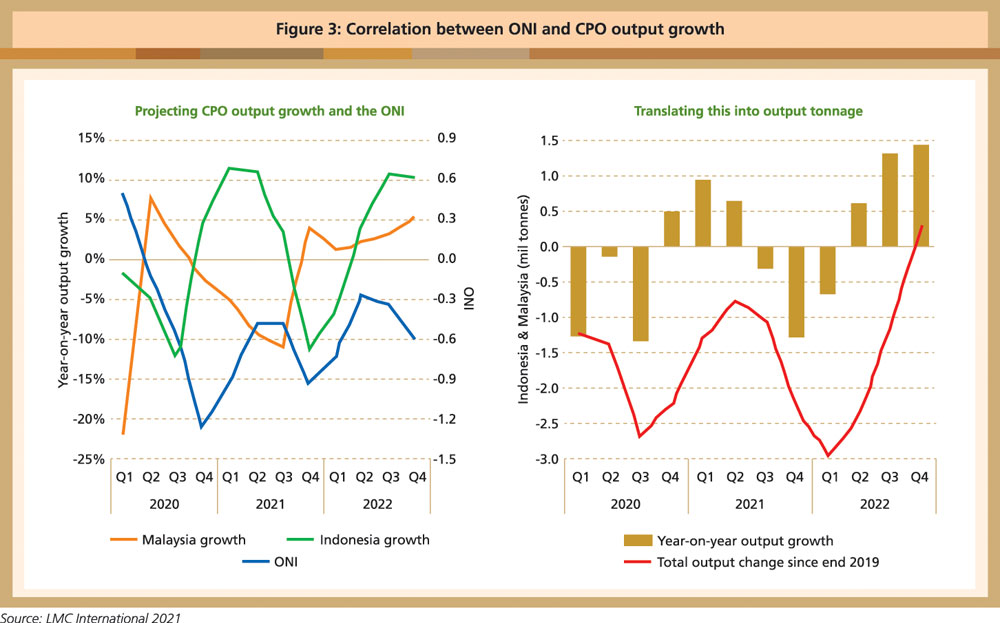

LMC International reports that Indonesia and Malaysia are in a long La Nina period in which the Oceanic Nino Index (ONI) is more negative than -0.5. The pattern of the ONI curve since 2020 echoes that of 2010-11, with La Nina weakening and then returning. If 2012 is taken as a guide, La Nina should end in 2022. A rising ONI is correlated with rising output growth, and a falling ONI is linked to slowing output growth. This is especially true for Indonesian production.

El Nino is a phenomenon of dry conditions for harvesting with the benefit of the previous year’s rains. With La Nina, there will be twin blows from heavy rainfall at estates and El Nino drought in the following years. In view of the apparent link between the ONI and output growth, in Indonesia, LMC International predicts that there will not be much palm oil production growth in 2022. The US National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration predicts a 95% chance of a weak La Nina lasting through February 2022.

Demand outlook

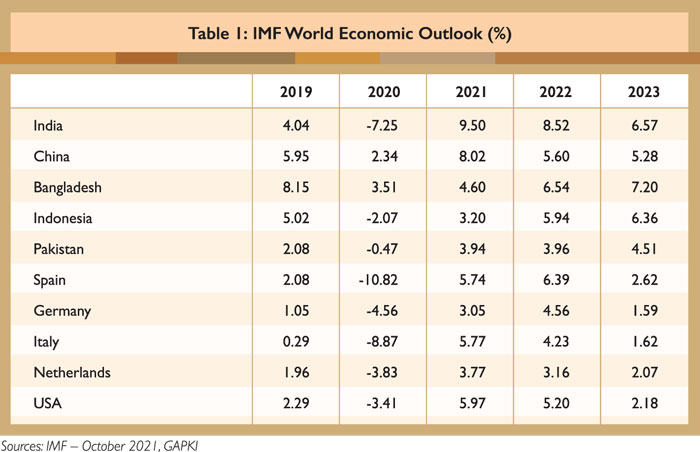

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its World Economic Outlook estimates that the global economy grew 5.9% in 2021 and will expand by 4.9% in 2022. The economic outlook will continue to be positive (Table 1).

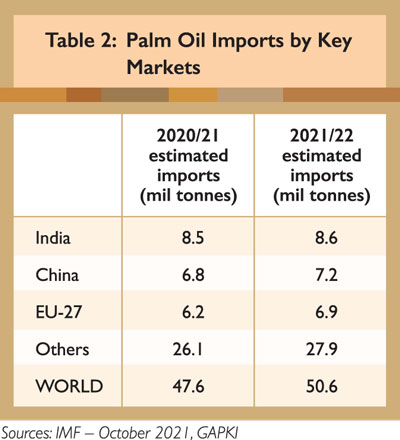

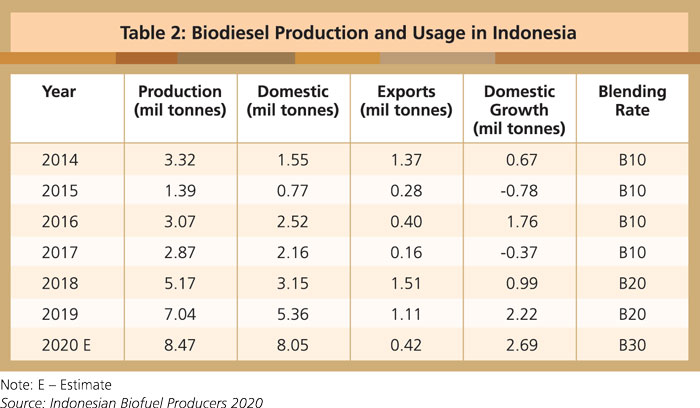

According to Refinitiv Agricultural Research, global palm oil demand for 2021/22 is forecast at 50.6 million tonnes, up 6.5 % compared to the prior season (Table 2), provided there is no large-scale demand destruction.

India’s palm oil purchases this year are estimated at 8.6 million tonnes in 2021/22. The slight increase is boosted by the reopening of business activities, multiple import tax cuts and lifting of import restrictions on RBD palm olein. However, the upside to higher palm oil imports is limited by its narrowing discount to soybean oil and sunflower oil.

Also, the Indian government implemented stock limits on edible oils in October 2021, regulating the stocks that retailers and wholesalers can carry. Despite higher domestic oilseed supplies (including soybean, rapeseed and groundnut) on the back of ample rainfall and planted area expansion, crushing activities have not kept up. So, lower domestic vegetable oil production may potentially prompt higher palm oil imports.

China is the world’s second-largest buyer of palm oil after India and imports about 6-7 million tonnes from Indonesia and Malaysia every year. This year, China’s palm oil consumption is expected to increase due to a lower supply of rapeseed oil and soybean oil. It is also seen to buy more palm oil products for animal feed.

China’s palm oil imports are expected to rise to 7.2 million tonnes in 2021/22 boosted by economic recovery. There were more shipments to China ahead of the Lunar New Year and Winter Olympics in February. However, the upside could be limited in the months ahead by recent higher soybean crushing activities amid better crushing margins, which will lead to higher domestic soybean oil supplies. Also, RBD palm olein’s discounts on soybean oil have been narrowing, thus potentially dulling consumer buying interests.

Exports to the EU are expected to be muted, partly due to unattractive palm oil prices for biodiesel blending and early implementation of the revised Renewable Energy Directive by some member-states. The European Commission’s proposed law and due diligence to require proof that agricultural imports are not linked to deforestation, could potentially dampen palm oil sentiment.

The EU-27 palm oil imports are estimated at 6.9 million tonnes in 2021/22. Although the reopening of economies and the competitive prices of palm oil versus other edible oils will likely increase overall demand in 2021/22, renewed lockdowns – following the discovery of the Omicron variant of the Covid-19 virus – have raised doubts. The impact on palm oil demand is unclear at this point.

Price outlook

Industry experts forecast a tight stock situation and higher prices to run into the first half of 2022. Key factors to watch are the pace at which foreign workers are allowed to return to Malaysia; the impact of massive floods at many oil palm estates in five states across Malaysia; high costs of fertiliser; and the impact of the Omicron variant on production recovery.

At the Indonesian Palm Oil Conference in December 2021, many market analysts forecast that palm oil prices would remain firm, supported by a limited vegetable oil supply in the first half of 2022. However, they differed as to when and how much the prices would fluctuate throughout the year.

LMC International indicates that tight supplies of palm oil, rapeseed oil and soybean oil have fueled the current high palm oil price. It cautioned that palm oil prices may be moderated by rising interest rates and hesitancy by major biodiesel users. It also predicted that there would be a small drop in the Crude Palm Oil-Brent premium until all vegetable oil output recovers in the second half of 2022. The key potential bullish factors that will keep prices higher are weather conditions until the first quarter of this year; a prolonged labour shortage at oil palm estates in Malaysia; oilseeds farmers refraining from selling; and biofuel policies.

GAPKI expects palm oil to stay above US$1,000 per tonne in the first half of 2022 and potentially for the rest of the year. It projects weaker output growth from Indonesian estates due to lack of new replanting, adverse weather and low fertiliser use. Indonesia’s palm oil stock for 2021/22 is forecast at 3.8 million tonnes, much lower than 4.9 million tonnes in 2020.

Palm oil trading trend in 2022 will depend heavily on the biodiesel mandate, which has been fueling price support. The success of the Indonesian Export Tax system provides significant insulation from further palm oil price volatility. This has also been aided by the level of vegetable oil stocks and the market’s tightness since the Covid-19 pandemic.

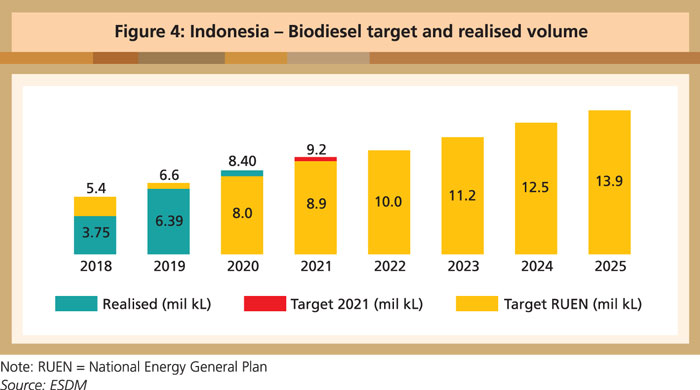

Indonesia’s B30 biodiesel mandate is likely to stay for 2022 and 2023 before the green diesel or hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) is commercially available. The government has raised the B30 biodiesel quota for 2022 to 10 million kilolitres. In 2021, Indonesia expanded its biodiesel allocation by 213,033 kilolitres to 9.4 million kilolitres. This will continue to support palm oil prices with the higher domestic demand.

Based on data from the Indonesian Palm Oil Fund Management (BPDPKS), the 2021 export levy collection is estimated at between US$4.87 billion and US$4.94 billion, of which US$3.4 billion or 70% is being used to support the B30 biodiesel programme. In 2022, BPDPKS estimates that the biodiesel mandate funding will be US$2.7 billion. Funding from the palm oil exports levy is still sufficient to support the mandate into 2022.

In 2022, Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources plans road tests on the B40 blend, in two options. The first is a 30% biodiesel and 10% HVO blend, and the second is a 30% biodiesel and 10% distillate fatty acid methyl esters combination. The government is executing a comprehensive study on the B40 blends and aims to partially implement this mandate in 2025. The biodiesel mandate and palm oil export levy collection are supportive of biodiesel production from 10 million kilolitres in 2022 to 13.9 million kilolitres in 2025.

Current developments look promising in the US. The USDA’s Economic Research Service recently projected higher soybean oil demand in 2022, while Rabobank foresees greater crush capacity beginning in 2023 as more renewable diesel facilities come online. Renewable diesel in the US has multiple government policies driving new production. The Renewable Fuel Standard generates renewable identification numbers for renewable diesel subsidy. There is also the US$1-per-gallon Biodiesel and Renewable Diesel Tax Credit that is set through 2022 but could be extended through 2026 in the Build Back Better Act.

Rabobank projects renewable diesel production to hit more than 6.1 billion gallons by 2030. That would push vegetable oil demand to about 21.4 million tonnes. To put that into perspective, Rabobank notes that the US is producing about 11-11.3 million tonnes. Basically, that requires double the volume of soybean and other vegetable oils to meet the demands of renewable diesel. Many analysts forecast continued high demand for soybean, inevitably boosting palm oil prices.

CPOPC is of the view that palm oil output will remain constrained with limited upside potentials, and that prices will likely continue to trade in the bullish range of US$1,000 per tonne. However, the palm oil price rally forecast in 2022 could be dampened by higher soybean oil output in Brazil.

In 2021/22, Brazil and Argentina’s soybean production is estimated at 147.9 and 45.8 million tonnes respectively. Record high soybean production is expected in the 2021/22 season unless adverse weather conditions amid La Nina significantly deteriorate growing conditions. The upside potential of soybean yields could also be limited by concerns over lower or delayed input applications, following soaring fertiliser and pesticide prices.

While these factors support bullish vegetable oils prices in 2022, there are worries over the recurrence of Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns due to the emergence of the Omicron variant, thereby slowing global economic recovery.

CPOPC

Jakarta, Indonesia

This is an edited version of the article which is available at

https://www.cpopc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CPOPC-OUTLOOK-2022.pdf

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Cover Story No Comments

MPOC sat down with Malaysia’s new Plantation Industries and Commodities Minister, the Hon. Zuraida Kamaruddin, to discuss the state of the palm oil sector; opportunities for market expansion in Asia; ongoing global regulatory threats; and claims of forced and child labour on plantations.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Wednesday, September 29th, 2021 in Issue 3 - 2021, Cover Story No Comments

In recent years, EU stakeholders have been considering the introduction of a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM). The idea is that, since the EU is heavily investing in a greener economy – which will raise production costs for its manufacturers – companies could be faced with less ‘green’ but more competitive ‘like products’ from outside the EU, where environmental regulation may be less strict and production less costly. Therefore, the EU is considering a mechanism that would penalise imports of carbon-intensive goods in order to level the playing field.

In the EU, certain emissions are currently regulated through its Emission Trading System (ETS). This is based on the ‘cap-trade system’ principle, where a limit is set on the amount of certain greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that may be emitted by defined industry sectors. Within the cap, companies can receive or buy allowances that can be traded with other companies.

The cap is then linearly reduced over time so that the total emissions decrease. The ETS covers the electricity and heat generation industry; commercial aviation within the European Economic Area; aluminium production; and certain energy-intensive industrial sectors like cement, glass and oil refineries. It does not apply to the agricultural sector.

A proposal for review of the ETS was published on July 14, 2021, as part of the EU’s ‘Fit for 55’ legislative package. The proposal extends its scope to the maritime sector and foresees the establishment of a separate self-standing ETS from 2025 for road transport, as well as for energy efficiency of buildings.

A main criticism of the ETS concerns the free allocation of allowances, which is used to safeguard ‘the international competitiveness of industrial sectors at risk of carbon leakage’. Carbon leakage refers to the situation in which EU production moves to non-EU countries that have less ambitious emission rules and lower production costs, due to less burdensome climate policies. Industries that receive free allowances are not obliged to reduce emissions at the same pace as industries that do not receive free allowances.

A 2020 report by the European Court of Auditors noted that industries receiving free allowances continue to represent 94% of EU industrial carbon emissions. In order for the EU to reach its target of zero emissions by 2050, free allowances would need to be reduced to zero. Therefore, the EU considers the CBAM as a key tool to address carbon leakage with a mechanism that seeks to ‘equalise’ GHG costs of imports with those of domestic production.

Last year, the European Commission (EC) invited the public to submit feedback on the legislative Roadmap on the CBAM, which is aimed at ensuring ‘that the price of imports reflects more accurately their carbon content’. The EC is also to design a new policy to reduce EU carbon emissions, addressing ‘carbon leakage’ and incentivising other countries to join emission reduction efforts.

The legislative Roadmap listed four options for the CBAM:

Until now, there has been no clarity on the design of the EC’s legislative proposal and on how the CBAM could work in practice. At the time of writing, a public consultation is being conducted, with submissions to be accepted up to Sept 10.

European Parliament’s stance

On March 10, 2021, the European Parliament adopted its position on the CBAM through a Resolution on ‘A WTO-compatible EU carbon border adjustment mechanism’. This position is to be taken into account by the EC, as it works towards the publication of its legislative proposal.

The Resolution underlines that the European Parliament supports the introduction of a CBAM ‘provided that it is compatible with WTO rules and EU free trade agreements by not being discriminatory or constituting a disguised restriction on international trade’; and that a CBAM ‘should be exclusively designed to advance climate objectives and not to be misused as a tool of protectionism, unjustifiable discrimination or restriction’.

Indeed, this should be the objective, but it remains to be seen if the EU will actually deliver on this or if the CBAM will protect EU businesses rather than the environment.

While the European Parliament assessed the four options being considered by the EC, the Resolution focuses on options 1 (import tax), 3 (which mirrors the ETS) and 4 (a ‘carbon tax’).

Most notably, the Resolution encourages the EC to pursue option 3 and to propose a CBAM based on the ETS. According to the European Parliament, while complying with WTO rules, the CBAM would need ‘to charge the carbon content of imports in a way that mirrors the carbon costs paid by EU producers’.

It should be noted that the option favoured by the European Parliament would not immediately affect the agricultural sector. In fact, under this option, the mechanism would mirror the ETS and its current coverage of sectors. The other options would not strictly follow the ETS sectors, which could mean that those options would cover a broader range of sectors, possibly including agriculture.

In its Resolution, the European Parliament recognised that products not falling under the ETS should be considered and that, in order to achieve the objectives of the European Green Deal, the CBAM mechanism should be accompanied by ‘necessary measures in non-ETS sectors’. Such measures could affect palm oil, as agriculture is a non-ETS sector.

The Resolution highlights that the option of an excise duty (option 4) on the carbon content of all consumed products – domestic and imported – would not ‘fully address the risk of carbon leakage’. It notes that this would be ‘technically challenging given the complexity of tracing carbon in global value chains and might place a significant burden on consumers’.

The Resolution further acknowledges that a fixed duty or tax on imports (option 1) could be a simple tool and would provide ‘a strong and stable environmental price signal for imported carbon’, but that – if the CBAM were to be of a fiscal nature – unanimity would be required in the Council of the EU.

Importantly, the Resolution ‘stresses that the CBAM should ensure that importers from third countries are not charged twice for the carbon content of their products’ and that ‘Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States should be given special treatment’.

Legal uncertainties

While the objectives of the CBAM are clear, many legal uncertainties remain. Consequently, the legal viability of the concept has yet to be determined. The EU should strive to develop a mechanism that complies with relevant WTO disciplines. How the EU designs and applies the CBAM will be crucial in determining its consistency with WTO rules, especially if the EU were to apply a border measure that only targets imports.

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) prohibits WTO Members from imposing tariffs and charges in excess of the levels committed in their respective Schedule of Concessions. In addition, the GATT prohibits levying internal taxes or charges in excess of those applied to ‘like’ domestic products.

The European Parliament proposes a CBAM based on the ETS so as to ensure that both domestic producers and importers pay the same carbon price. Notably, a difficulty arises when assessing whether the charge levied by a WTO Member on an imported product is equivalent to that applied to the domestic product – for example, where the importing country does not maintain a simple tax scheme, but a more complex scheme, such as the ETS.

With respect to the issue of ‘likeness’ under Article III of the GATT on ‘National Treatment on Internal Taxation and Regulation’, processing methods cannot currently be used to classify two products as different (or not ‘like’). EU policies that discriminate against imported products vis-à-vis ‘like’ domestic products, based on how they are produced, risk being incompatible with WTO rules, notably with the non-discrimination principle. Therefore, a CBAM would run the risk of being inconsistent with WTO rules.

Article XX of the GATT on ‘General Exceptions’ does allow WTO Members to adopt certain (otherwise discriminatory) measures, for instance when they are justified in order to protect human, animal or plant life or health, or when they relate to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources. Both exceptions are subject to strict requirements and, over the years, in the majority of disputes, WTO Members have failed to successfully justify their environment-related measures under Article XX.

In particular, the exception for measures to protect human, animal or plant life or health would need to pass the necessity test; this would determine whether such measures are ‘necessary’ to achieve the policy objectives being pursued.

To consider a measure ‘necessary’, a WTO panel would need to assess the extent of the measure’s contribution to the achievement of its objective; and its trade restrictiveness in light of the importance of the interests or values at stake.

Concerns expressed

While the EU may be pursuing legitimate objectives with its environmental policies that drive up its costs, such regulatory requirements should not be detrimental to businesses around the world which are already subject to domestic requirements.

Countries like Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan and Singapore have already expressed concern, indicating that they perceive the CBAM as a unilaterally imposed and potentially protectionist measure that would be discriminatory and negatively affect trade.

They point out that countries in Asia and the Pacific region have been developing or already have their own carbon pricing approaches, which the EU might not be taking into account. Therefore, these countries have asked the EU to create a CBAM that would take their measures and mechanisms into consideration.

More specifically, certain Asian countries and in particular Indonesia and Malaysia, have called on the EU to work with third countries and not to take a unilateral decision that would cause a situation comparable to the discrimination of palm oil under the EU’s revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED II). Additionally, several countries have said that the EU should use the revenues generated by a CBAM to help developing countries in their decarbonisation efforts.

Any CBAM introduced by the EU must be implemented in the least trade-restrictive manner possible. However, it can already be expected that any such mechanism, regardless of its design, will be challenged by other WTO Members.

Given existing EU policies, such as the RED II, it should also be clearly advocated that the CBAM should not apply to agricultural products, including palm oil.

On April 26, 2021, EC Executive Vice-President and Commissioner for Trade Valdis Dombrovskis stated that the proposal on the CBAM was only the beginning of the discussion.

Stakeholders, including those in Malaysia, should therefore ensure that their perspectives and positions are heard, in order to achieve a balanced and non-discriminatory mechanism – ideally one that is based on multilateral approaches and not on unilateral obligations.

Dato’ Dr Wan Zawawi Wan Ismail

CEO, MPOC

By gofb-adm on Saturday, July 17th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Cover Story No Comments

The Centre for Sustainable Palm Oil Studies (CSPO) has partnered with EU Parliament Magazine to produce a supplement highlighting efforts to promote the use of sustainable palm oil. The supplement, titled ‘Sustainability First: The prospects of sustainable palm oil certification and consumer action to tackle deforestation’, underscores the CSPO’s mission, achievements and ‘Sustainability First’ campaign.

Published in print as well as posted online, the supplement features insights from CSPO board members, researchers and stakeholders. The authors cover a variety of relevant issues pertaining to palm oil, deforestation and sustainability, using the unique opportunity to highlight possible new partnerships on palm oil instead of a ban.

Introducing the supplement, CSPO Advisory Board Chairman Dr Ibrahim Özdemir, a world-renowned ecologist and UNEP consultant, renews calls for Europe to use its Green Deal to work with international partners to confront the threat of climate change and deforestation in order to build a sustainable future.

Özdemir warns that there is often conflict between the EU’s perceptions and the realities of sustainability. The case of palm oil exemplifies this conflict. As a ‘forest-risk commodity’, palm oil is often blamed for deforestation; yet, policy makers ignore the positive developments in supply chain transparency and renewed international collaboration, such as the EU-ASEAN Joint Working Group on Palm Oil.

Malaysia – the world’s second-biggest producer of palm oil – has witnessed a yearly decrease in deforestation since 2016. This milestone is partly attributable to the nationally mandated Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification scheme. Importantly, the success of MSPO can be used as a vital template for harmful forest-risk commodities like soybean or beef.

The ‘Sustainability First’ campaign, which collates palm oil research, expertise and analyses to inspire fact-based conversations pertaining to sustainable palm oil, hopes to enable a new generation of ethical consumers. By breaking misconceptions surrounding palm oil, the accomplishments of the MSPO can leverage the opinions and choices of European consumers. If consumers and the successes of the MSPO are used to influence policy, new sustainable consumption patterns could shape environmental sustainability.

Therefore, the time is now for policy makers to embrace practical global solutions for sustainable consumption, trade and production.

Contextualising deforestation drivers

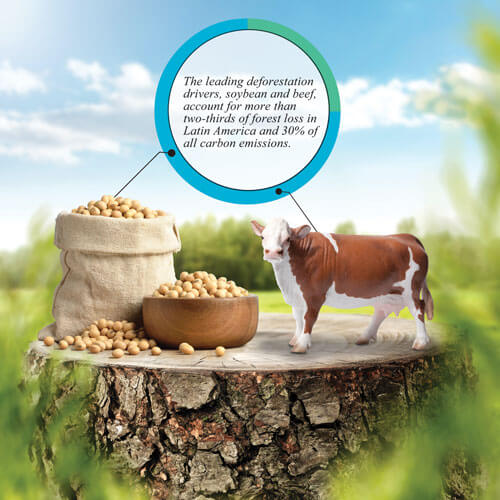

In providing a broader picture of deforestation, environmental activist and food ethics researcher Isabel Schatzschneider writes about forest-risk commodities. According to a study by non-profit organisation CDP, agriculture and forestry contribute to more than 80% of global deforestation. The leading deforestation drivers, soybean and beef, account for more than two-thirds of forest loss in Latin America and 30% of all carbon emissions.

The palm oil industry now faces a 2030 ban for biofuels use in Europe, but the beef and soybean industries encounter little scrutiny, underscoring the hypocrisy in how palm oil is treated by EU policy makers.

While the palm oil industry has made leaps and bounds in addressing deforestation, the beef and soybean industries are failing. They both lack sustainable certification schemes and operate under notoriously opaque supply chains. Consequently, in Brazil, deforestation has reached a 12-year high.

Malaysia designed the MSPO with the EU in mind; and yet, the bloc is ignoring its ability to reduce deforestation, missing a vital opportunity to collaborate with and improve such systems. If the EU is serious about addressing deforestation, it must recognise the progress made in sustainable palm oil production as well as consider the environmental impacts of the other commodities.

Dr Nafeez Ahmed, the executive director of the System Shift Lab and research fellow at the Shumacher Institute for Sustainable Systems, writes that the EU’s de facto ban on palm oil will have unintended and far-reaching consequences.

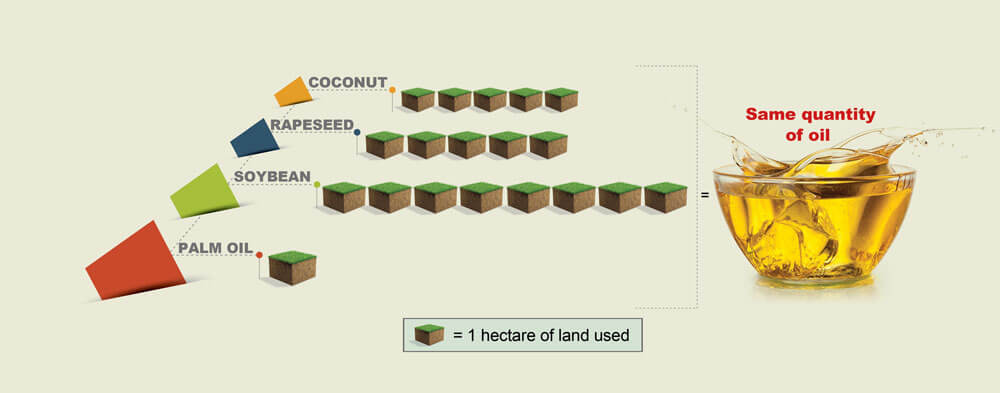

Nafeez reminds readers that the ban will increase the production of less sustainable biofuels and displace the effects of deforestation. Alternative oilseeds such as soybean, rapeseed, coconut or sunflower all require more land, water and fertiliser. Palm oil, which produces 35% of the world’s vegetable oil supply on less than 10% of the allotted land, is incredibly efficient – all other alternatives would require four to 10 times more land to produce the same amount of oil.

Also, the palm oil ban does not consider how it could reverse all progress. For instance, if the EU ostracises Malaysian Palm Oil, it is effectively telling smallholders that their efforts to produce sustainable palm oil has been for nothing.

Not only would this disincentivise sustainable production, but it could also lead to producers selling palm oil to ready markets with fewer environmental restrictions. For example, both India and China care less about sustainably produced palm oil; therefore, there would be less reason for smallholders to invest in sustainable measures.

Overall, the EU’s palm oil ban does not consider the negative effects of a one-dimensional boycott. More so, it verges on European protectionism as all of its alternatives are domestically cultivated crops. In summary, the EU will contribute to a rise in domestic deforestation, possibly curb sustainable progress, and place palm oil at a competitive disadvantage.

Robert Hii, the editor of CSPO Watch and commentator on sustainability and nature conservation, lauds the success of the MSPO. He believes it has successfully addressed many palm oil-related concerns, and states that progress should be rewarded with trade agreements which foster continued development.

The MSPO’s leading approach is defined by its ability to use tough law enforcement to tackle deforestation and human rights abuses, and commit to wildlife protection and biodiversity. The scheme also offers protection for endangered species such as the pygmy elephant and Bornean orang utan. Its ability to create a model for sustainable development has not gone unnoticed, and brands such as Unilever and Nestle have pledged support.

Part and parcel of the MSPO’s success comes from its innate ability to connect all the stakeholders involved in palm oil production, including smallholders (see Box). This inclusivity is something the EU should aspire to. If it could partner with Malaysia and lend its guidance to strengthen MSPO, then the palm oil supply chain would continue to transform and benefit those involved.

Sustainable innovation consultant and founder of sustainable streetwear brand KinArmat, Mariam Harutyunyan, highlights how the Covid-19 pandemic has inspired consumers to make more environmentally- conscious purchases.

Consumers, in turn, are demanding transparent and traceable supply chains, proving they have increasing power when it comes to effecting policy change. As palm oil is found in almost 50% of packaged products, its role in tackling deforestation and addressing consumer needs is crucial.

Consumers have notoriously condemned palm oil in the past. They have, for instance, criticised the cosmetics industry for its association with palm oil without realising that its substitute – coconut oil – uses five times the amount of land to produce the same quantity of oil.

It is important that consumers recognise that the palm oil industry is making huge progress in regard to deforestation – 98% of oil palm companies have taken at least one measure to reduce forest loss. The MSPO continues to be a leading template of success and ingenuity.

Green trade war?

Muhammed Magassy, member of the CSPO Advisory Board, Gambian Member of Parliament and National Assembly of Gambia and the Parliament for Economic Community of West African States, expresses his belief that the EU’s impending palm oil ban will have far-reaching consequences. The planned boycott may not only reverse progress in sustainability, but also lead to a green trade war with colonialist undertones.

The EU seems to be deciding the rules of global trade without considering the world’s poorest, mainly the millions of smallholders who will be affected by the palm oil ban. Smallholders, who have relied on oil palm cultivation to lift themselves out of poverty, are increasingly worried about being excluded from the EU market, especially in light of Covid-19 which has increased economic insecurity in developing countries. Magassy is concerned that the ban will push smallholders away from sustainable production which involves economic investment.

He also views the ban as more than an example of unfair policy with unintended consequences. The ban verges on protectionism as European oil seeds would be needed to replace palm oil. Rather than punishing emerging economies and protecting domestic production, the EU should aspire to create an even playing field – one which rewards sustainable progress and pursues collaborative frameworks of production and consumption.

However, Glenn Schatz, a member of the CSPO Advisory Board and co-founder of ECORE Ventures, sees the tide turning in EU opinion. Recent reports and opinions released by various arms of the European Parliament are urging MEPs to pursue inclusive partnerships with the Global South in order to prevent deforestation.

The UK’s new Environment Bill will force companies to prove compliance in their supply chains in accordance with local environmental laws and standards. And the Joint Working Group on Palm Oil, established last December, has pledged to increase communication between the EU and ASEAN.

This is promising. While the MSPO continues to progress and transform sustainability practices across Malaysia, the EU’s support will enforce and expand further green policies. An area of potential partnership could be through sharing satellite images which would help Malaysia identify and address areas of concern. If the EU truly cares about the climate, it must consider a trade partnership with ASEAN.

As the sustainability debate ramps up in Europe, with recent conversations around e-fuels and the carbon tax escalating, sharing the realities of sustainable palm oil has never been more important. Through the ‘Sustainability First’ campaign, the CSPO will continue contributing towards this debate and sharing pioneering developments in the industry.

The Centre for Sustainable Palm Oil Studies

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Cover Story No Comments

Even the most well-intentioned efforts can go awry. Policies meant to accomplish one outcome, or prevent another, sometimes have unforeseen effects. The European Union (EU) is not exempt.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Cover Story No Comments

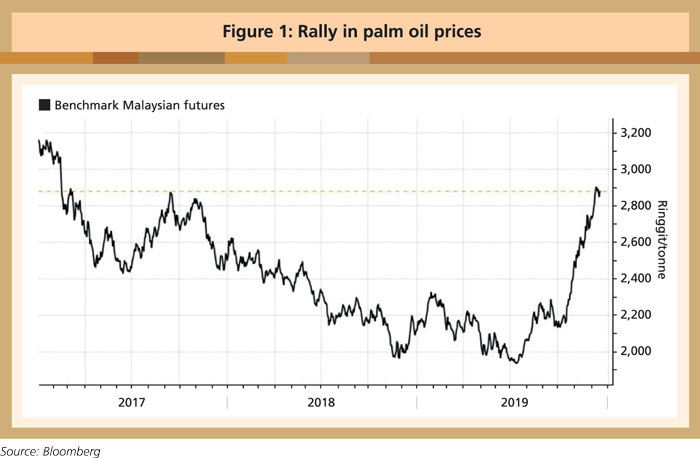

The crude palm oil (CPO) price rally since June 2020 has been driven by supply disruptions in key edible oils, as well as in palm oil producing regions. With demand outpacing supply, the Bursa Malaysia Derivatives Exchange’s third-month benchmark price passed RM3,000 to trade at RM3,064 per tonne by mid-October. This was 38% higher from a year ago. On Nov 13, it hit its highest level, reaching RM3,490 per tonne.

Palm oil output from Indonesia and Malaysia was adversely affected by drought and reduced fertiliser application in 2019. This was compounded by labour shortage and movement restrictions due to the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. Indonesia and Malaysia produce about 85% of the global palm oil supply. The lower-than-expected supply of other edible oils, particularly sunflower and rapeseed oils, had induced the sharp rise in vegetable oil prices, which then had a spillover effect onto CPO prices.

Although the Covid-related partial lockdowns imposed in many countries had curbed demand for edible oils, the reduction in palm oil exports was short-lived. By the second quarter of 2020, key importing countries had started to re-stock. Also, reduced availability of used cooking oil and animal fats due to the pandemic has led some biodiesel producers to switch their feedstocks to vegetable oils, which also boosted global demand for palm oil.

At the Virtual Palm and Lauric Oils Price Outlook Conference & Exhibition in October, most analysts concurred that CPO prices would likely trade above RM2,500-3,000 per tonne for the rest of the year. This is due to tight palm oil stocks, concerns over the La Niña impact on edible oil supplies, and labour constraints in Malaysia which will impact fresh fruit bunch (FFB) yields in the coming months.

The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) is of the view that palm oil prices are likely to stay high in the first half of 2021, amid lower soybean crushing in Argentina and rising sunflower oil prices. Another key factor to watch is the weather pattern and the severity of La Niña going forward. Ongoing La Niña heavy rainfall has started to disrupt output in Southeast Asian palm oil producing countries. This will subdue global supply until the first quarter of 2021. Towards the second half of 2021, adequate rainfall and better crop management incentivised by the current high palm prices will significantly boost production.

Oil World recently forecast that vegetable oil prices in 2021 should trade higher due to improved demand and a tighter supply of soft oils such as soybean and sunflower oils. It indicated that soybean oil would lead the way. The rally in sunflower oil due to a lower crop harvest has also made soybean oil and palm oil attractive to price-sensitive buyers. China’s edible oils re-stocking policy is expected to continue in the months ahead with fund buying. Combined with Argentina’s soybean crushing problems, this could further boost palm oil prices.

Market outlook

Covid-19 pandemic

This is unlikely to have any severe impact on vegetable oil demand, including palm oil. This is because edible oils are a daily necessity, as a kitchen staple, cleaning agent or renewable fuel, in many people’s lives throughout the world.

In fact, the rising demand for oleochemical products has sustained demand for edible oils, including palm oil. Oleochemical derivatives such as glycerine, fatty acids and methyl ester, are the raw material for sanitisers, detergents and soaps which are experiencing rising demand due to better hygiene awareness and government-mandated health protocols.

Since the start of the pandemic, there has been a shift from business-to-business channels to business-to-consumer consumption habits with many households cooking and eating at home. The benefit of this change is that consumers will be changing their vegetable oils more regularly, as companies are selling smaller packs to consumers in the light of lower demand from restaurants.

Biodiesel mandate

The Indonesian B30 mandate will help absorb the increase in palm oil supply in 2021. The wide gap between biodiesel and diesel prices has led to the accelerated drawdown of the Indonesian CPO fund. The earlier concerns about Indonesian biodiesel usage that might contract in 2020 will not happen, as the B30 biodiesel mandate will be fully implemented until the end of 2020.

However, the spread of palm oil to gas oil and low diesel price translates into expensive biodiesel mandates. As such, any revision or abandonment of biodiesel mandates would exert downward pressure on prices. In this context, it is crucial for both main producing countries to implement the biodiesel mandate, which is B30 for Indonesia and B20 for Malaysia. The use of palm oil biodiesel in the European Union could slow down if the supply of used cooking oil returns to the market with more economic activities opening up in 2021.

La Niña

The price outlook for 2021 will depend on the development of La Niña and its impact on the soybean complex in South America. Should there be a severe La Niña event, there will be lower soybean production. This, combined with a limited supply of sunflower and rapeseed oils from the Black Sea region, will result in higher vegetable oil prices in the first half of 2021. In this scenario, CPO prices will also benefit.

It is also noted that soybean crop replanting in Brazil and Argentina has been delayed due to the current dry weather conditions. If this persists, soybean yields in the coming season will be impacted. If the La Niña conditions advance into April 2021, this may also hurt soybean plantings in the US.

Oil palm replanting

The CPOPC sees structural changes in the global palm oil supply from 2021 due to a slowdown in new oil palm plantings throughout Indonesia and Malaysia since 2015. With the ageing tree profile across both countries, the replanting programme will also temporarily limit palm oil supply in the short to medium term.

As agricultural land becomes limited, oil palm replanting will be key to boosting palm oil yield across Indonesia and Malaysia. It is important to replant so as to sustain supply in the long run. Replanting is especially important for smallholders because their trees respectively account for 42% and 40% of Indonesian and Malaysian oil palm plantations.

Production outlook

There are three key drivers to the palm oil supply and growth prospects in 2021 – area expansion; oil palm tree age and yield; and weather.

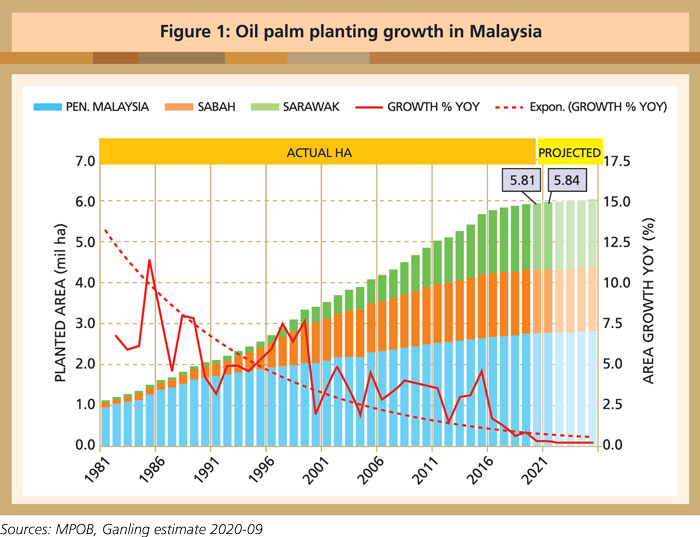

A recent Rabobank Group report highlighted that the slowdown in new plantings is due to a moratorium by the Indonesian and Malaysian governments on agricultural expansion and low commodity prices. Malaysia has capped its oil palm planted area at 6.5 million ha. To date, Indonesia has limited agricultural land availability and approved concession areas of up to 4 million ha. This structural change will impact the global palm oil supply from 2021. The replanting of 500,000 ha of oil palm by Indonesian smallholders, by the end of 2022, should sustain palm oil supply for the world.

According to Ganling Malaysia, the ongoing declining palm oil yield is due to ageing trees across Indonesia (24%) and Malaysia (30%). Any catch-up in replanting will temporarily limit the supply growth in the short to medium term. In Indonesia, replanting at an average of 1% per annum will take about 1.5 million tonnes out of the supply chain, while in Malaysia, the replanting rate average at 1.8% per annum is expected to withdraw about 1.1 million tonnes. The total withdrawal will be about 2.6 million tonnes out of the potential supply chain in 2021.

The La Niña weather pattern, which induces higher rainfall throughout tropical Indonesia and Malaysia, should boost fruit yield and CPO output in 2021. However, higher rainfall could also lead to flooding, which could hurt output and support prices.

The Meteorological, Climatological and Geophysical Agency of Indonesia has forecast a low-to-moderate intensity La Niña in the last three months of 2020. The agency expects about 55% of Indonesia to receive higher rainfall than average. Generally, Southeast Asia, South Africa, India and Australia receive above-normal rainfall due to La Niña, while Argentina, Europe, Brazil and the southern US experience drier weather. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has also stated that there is a 75% chance that La Niña will stay for the entire winter, into early 2021.

La Niña is likely to result in a drier climate in the Eastern Pacific and South America, a major area for soybean production. Soybean yields could drop in Argentina and Brazil due to drought-like conditions, which will then support soybean oil prices. Since palm oil and soybean oil are the two most consumed vegetable oils globally, their prices are positively correlated due to easy substitution.

Due to the movement control measures amid the Covid-19 pandemic, Malaysia has banned foreign workers from entering the country. Since foreign labour accounts for 75% of Malaysia’s oil palm plantation workforce, the shortage of workers will lead to palm oil production setbacks in crop losses. A prolonged labour shortage is expected to trigger a larger-than-expected drop in CPO output this year and in 2021.

Indonesia has also enforced large-scale social distancing measures to curb Covid-19. While plantations have imposed strict hygiene measures and restricted workers’ movement, supply disruption is expected to be limited as palm oil producers have no plans to halt operations.

Demand outlook

In 2021, palm oil imports by key destinations are expected to improve slightly from 2020, with the exception of Europe, according to Refinitiv Agriculture Research, Singapore. Economic activities in key palm oil destinations are recovering more swiftly than anticipated, thanks to the resumption of business activities and financial stimuli. Palm oil demand from India and China is expected to grow in 2021.

India’s palm oil imports are expected to spike by 4.8% to 8.7 million tonnes, boosted by a gradual recovery in demand, as well as low inventories. There will be re-stocking and higher demand from bulk buyers in the hotel/restaurant/café sectors after slower demand during the Covid-19 lockdowns. While there has been a surge in palm oil exports to India, domestic crop cultivation, especially soybean, appears to have risen too. Therefore, if there are very good harvests of the rapeseed, groundnut and soybean crops in 2021, India could curtail its palm oil purchases.

China’s demand for palm oil is anticipated to edge up by 3% to 6.9 million tonnes in 2021. The market has seen strong demand for palm oil in anticipation of the Chinese New Year celebrations that typically fall in January or February, as well as due to re-stocking.

EU palm oil imports will likely decline by 8.6% to 6.4 million tonnes, partly due to its policies. Palm oil biodiesel (considered as ‘high risk’ for indirect land-use change under the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive II) usage will be gradually reduced from 2023 until 2030.

Moreover, the EU has set new food safety standards on 3-MCPDE and GE, contaminants found in refined oil products, potentially affecting palm oil demand in the food sector. As the Covid-19 pandemic leads to widespread restaurant closures and lower biodiesel use, overall consumption of palm oil is expected to be reduced in Europe.

Refinitiv also reports that Indonesia and Malaysia have continued to support the B30 and B20 biodiesel programmes respectively, despite subdued biodiesel consumption during the pandemic resulting from social distancing measures and movement control orders, as well as the high CPO premium over gas oil.

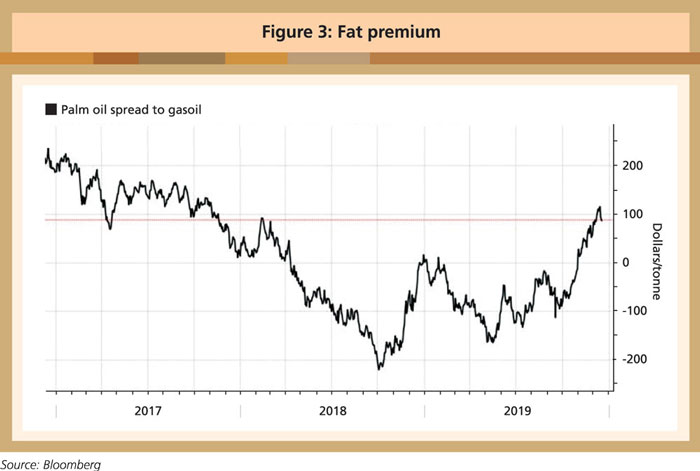

The price spread between palm oil and gas oil has been widening since the last quarter of 2019 to the peak of US$400 per tonne level. But in September 2020, it stabilised at around US$370, the highest since April 2016.

Due to the CPO premium over gas oil, the Indonesian government has allocated 2.78 trillion Rupiah to support the B30 programme for 2020.

Malaysia’s B20 mandate was restarted in Sarawak on Sept 1, 2020. It will be implemented in Sabah and Peninsular Malaysia in January and June 2021 respectively. Biodiesel mandates are anticipated to absorb around 10 million tonnes of CPO from both palm oil producing countries in 2021. This will support domestic consumption and reduce palm oil inventories.

It is projected that the palm oil market will likely trend up in the near-term in tandem with soybean prices, which is mainly supported by higher demand for soybean from China; lower global soybean stock estimates by the US Department of Agriculture; and unfavourable weather in the US Midwest and South America (namely Argentina and Brazil). One example would be Brazil’s current drought, which has delayed soybean plantings, thereby supporting soybean prices. La Niña could also limit the soybean oil yield potential.

Price and supply outlook

As at November 2020, palm oil futures on Bursa Malaysia Derivatives Market were trading above RM3,000 per tonne. If this continues for the rest of the year, palm oil prices will probably average around RM2,600-2,650, a return to the more optimistic prices of 2017.

Based on tighter supply-demand dynamics and low palm oil stocks, the CPOPC sees the momentum continuing until higher production resumes in the second half of 2021. The wider CPO price discount to other vegetable oils is also supportive of global palm oil demand. Droughts in the Black Sea region are also limiting sunflower and rapeseed production. This will result in elevated vegetable oil prices well into the first half of 2021. At the same time, the developing La Niña may cause some disruptions to soybean production in South America. If the dry weather persists, there will be more severe soybean oil disruptions in Brazil and Argentina.

Current edible oil stockpiles in China and India are also tight, keeping edible oil imports healthy. The price surge in the last quarter of 2020 reflects the rapidly recovering demand from India and China, the world’s two biggest palm oil consumers after they went through nationwide lockdowns and temporary halts on economic activities due to Covid-19. The rise in competing edible oil prices is also positive. It could encourage consumers to switch to palm oil as a cheaper alternative.

Many analysts agree that palm oil supply will improve in the second half of 2021 due to the effect of higher rainfall, which should be beneficial for FFB yields. Both Ganling Malaysia and Rabobank foresee that good weather conditions in Indonesia and Malaysia will raise global palm oil supply by 3.1 million tonnes in 2021.

There are also concerns that the current zero export tax for CPO in Malaysia may not be extended beyond Dec 31, 2020. This could negatively impact CPO exports to India, while Indonesia could raise its CPO export levy to support its B30 mandate.

On the whole, the palm oil outlook in 2021 looks favourable compared with the average prices of 2019 and 2020. However, this will depend on the development of La Niña on the soybean complex in South America and Indonesia’s B30 biodiesel mandate. The full implementation of the B30 mandate in Indonesia and the B20 mandate in Malaysia is crucial to sustain domestic consumption and absorb the anticipated palm oil supply growth. A deficit situation in global vegetable oils will lend support to CPO prices in 2021.

Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries

Jakarta, Indonesia

This is a slightly edited version of the report published in December 2020.

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Cover Story No Comments

The Hon. Dato’ Dr Khairuddin Aman Razali was appointed Malaysia’s Minister of Plantation Industries and Commodities in March, following the takeover of the government by Perikatan Nasional (PN) in February. In an interview, he highlights strategies to cope with ongoing issues in the palm oil sector, including challenges being thrown up by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Covid-19 has caused widespread suffering for oil palm smallholders, whose income has fallen due to the lower price of palm oil. How is your Ministry helping them?

Dato’ Dr Khairuddin Aman Razali: Smallholders have always been an important stakeholder in our palm oil industry. Over the years, the government has introduced various initiatives to help them succeed and improve their livelihood. To ease the impact of poor returns due to Covid-19, the government has allocated RM350 million in microcredit financing via Agrobank, at an interest rate of 3.5%, to help agropreneurs. This serves as another option for smallholders to finance plantation activities.

Currently, the Oil Palm Smallholder Replanting Financing Scheme and Oil Palm Smallholder Agricultural Input Scheme already assist smallholders with replanting old and unproductive oil palm trees with high yielding seedlings; in the long term, this will improve the yield and generate higher income.

Apart from that, the government is actively encouraging smallholders to participate in the Sustainable Oil Palm Planters Cooperative (KPSM). This aims to increase income through higher productivity via the implementation of Good Agricultural Practices and auxiliary activities. The main activity of the KPSM is the establishment of weighing centres to purchase fresh fruit bunches (FFB) from smallholders.

Under the 11th Malaysia Plan, the government has provided an incentive of RM200,000 per KPSM to build weighing centres. To strengthen capacity in FFB trading, the government – through the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) – has created a revolving fund for selected high performing KPSM. This serves as working capital support to offer a better price for FFB than that offered by middlemen dealers.

Through the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry, and working with MPOB, the government has launched the Cash Crop Programme for independent oil palm smallholders in the B40 [low-income] category; each participant gets RM3,000 to plant bananas and RM7,000 to plant pineapples. Additionally, an incentive scheme helps smallholders to venture into rearing livestock, such as cattle and goats, for extra income especially during a downturn in palm oil prices.

One main issue in the industry is the shortage of plantation workers. How do you see this impacting the industry, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic?

The labour shortage has affected productivity in all sectors. In the oil palm industry, there are vacancies in harvesting operations for about 36,000 people around the country. It is disheartening that some are reluctant to work in estates, and we have had no choice but to get in foreign workers. The problem was felt more acutely during the Covid-19 lockdown period earlier this year.

However, I look at this from a positive angle. The pandemic has made us realise how much we have been dependent on foreign workers. We need to woo more Malaysians to join the plantation sector. With many being laid off due to the economic impact of Covid-19, it would be good for them to seek employment in the plantation sector. We have implemented a minimum wage as stipulated by law. Some main industry players are currently paying double the amount, in addition to providing free accommodation and other perks. This information needs to be promoted more effectively to attract locals.

In trying to draw in the best workers, my Ministry has set up a special task force on plantation labour to see how best we can assist unemployed locals and match them with specific needs in the industry. The MPOB, meanwhile, remains very active in research and development to mechanise plantation activities. I truly believe that, through sheer determination and cooperation with all involved, Malaysia can address the shortage of workers. Further information can be obtained from MPOA and MPOB.

Since the PN took over the government, diplomatic ties with India have improved. Does this warmer relationship have any bearing on India’s intake of Malaysian palm oil?

I am glad that diplomatic ties between India and Malaysia have improved. The Right Honourable Prime Minister himself met with the Indian Envoy stationed in Kuala Lumpur. The improvement is evident in the increase in bilateral trade. We in the Ministry have also worked hard toward this.

The latest figures from the Department of Statistics show an increase in the value of exports of palm oil and its products by 544% in June (valued at RM633.5 million), compared to May (RM98.3 million). In June, India imported 246,045 tonnes of palm oil, compared to 10,806 tonnes in March – a 23-fold increase. We hope the trend will continue as the year progresses. My Ministry will work hard to ensure exports rise and to explore new markets.

Recently, I had a virtual discussion with H.E Singireddy Niranjan Redy, Minister of Agricultural, Co-operation, Marketing, Food & Civil Supplies, and Consumer Affairs in Telangana, India. I conveyed our hope that the Indian government will import more palm oil and palm-based products.

Mr Redy sought Malaysia’s expertise in oil palm cultivation to expand plantations in Telangana. I told him that the Malaysian government is willing to provide such expertise and that I hope India will provide sandalwood seedlings in exchange. Telangana is also impressed by our enthusiasm for the bamboo sector and has requested collaboration and possible investment by Malaysian companies.

Apart from that, my Secretary-General and his entourage paid a courtesy call on the High Commissioner of India to Malaysia. Their discussions focused on further improvement to diplomatic and trade relationships, especially in the commodities sector.

The European market has been hostile to palm oil, over alleged issues of sustainability and health. This shows that we cannot rely on a particular market to sell our palm oil. What do you have in mind to address this?

Palm oil has long been targeted because it is the most efficient oil-bearing crop in terms of production, land utilisation, pricing and versatility. This explains why the European Union (EU), as a main producer of rapeseed oil, is hostile to palm oil as a competing product. I am sad to note that the EU is reluctant to take into account our efforts toward sustainable production of palm oil, as well as communication with its parliamentarians and government officials. They continue to treat palm oil unfairly, so Malaysia has had no option but to seek action by the World Trade Organisation.

I agree that we cannot put all our eggs in one basket. We can target markets in the Middle East, Africa and Central Asia. They have a lot of potential that we can capitalise on, such as rising consumption from a growth in population.

Other than the Covid-19 pandemic, what factors have affected the demand for and price of Malaysian palm oil this year?

Firstly, many regard the trade war between the US and China as detrimental to the global economy due to the uncertainties created. When China agreed to buy more agricultural products from the US as part of their first trade deal signed in January, we anticipated that Chinese demand for Malaysian palm oil would be badly hit because of direct competition from soybean oil.

Indeed, our exports to China decreased by almost 16% in the first quarter of 2020, compared to the same period a year before. However, as tensions escalated between the two superpowers, we saw higher Chinese imports of our palm oil in the second quarter. It is hard to predict how the trade war will play out. We will monitor the situation closely and assess its impact on palm oil from time to time.

Secondly, restrictions on global and local travel to curtail Covid-19 have impacted the demand for biodiesel. Malaysia has delayed the implementation of its B20 programme until September for Sarawak and early next year for Sabah. As countries start to open their borders, I expect the demand for biodiesel to improve.

Thirdly, the breach in diplomatic ties between Malaysia and India did not help the palm oil industry. We lost quite a bit of exports during that period because India is our biggest buyer. But I believe we have mended this, as mentioned earlier.

Fourthly, we face continuous competition with other palm oil producers that could offer discounted prices. In dealing with this, my Ministry and its agencies have worked hard to maintain relationships with current buyers and to promote Malaysian palm oil to new ones.

The Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification scheme is a strategic approach by the government to enhance the competitiveness and marketability of Malaysian palm oil in the global market. What is the progress of the scheme, given the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic?

I have been involved in promoting the MSPO on the ground. At the events I attended, I sensed that awareness among smallholders with regard to the scheme and the necessity to get it implemented across the board has improved. They now understand why the government is serious about the scheme and why certification is mandatory. As at Aug 25, MSPO certification had been completed for about 86% or 5.1 million ha of the oil palm planted area.

While I am of course proud of this achievement, there is still much work to be done, particularly when it comes to certifying the independent smallholders. Collectively, 293,585 oil palm smallholders have received the MSPO certification. However, the majority are organised smallholders who are managed and certified under agencies such as FELDA and FELCRA.

We have only managed to certify 24.3% of the 986,331 ha of oil palm planted by independent smallholders. We will help to get them on board the MSPO through programmes such as Sustainable Palm Oil Clusters, to meet our target of 100% compliance with the scheme.

Recently, there was discussion that bamboo will replace palm oil as Malaysia’s top commodity. Was this a misunderstanding?

The debate on this in the Parliament was wrongly interpreted. At no point did I say that bamboo would replace palm oil as our main commodity. Our intention was merely to explore the economic viability of bamboo as an alternative commodity. The preliminary studies conducted locally have indicated that bamboo has the economic potential to generate lucrative income.

I would like to assure all palm oil stakeholders that the government will protect the interests of the industry and strengthen it. Among the measures being undertaken are application of the latest technology in the upstream sector; expansion of markets; diversification of value-added products; and studies that focus on the benefits of palm oil.

Can you tell us more about the ‘Sawit Anugerah Tuhan’ (‘Palm oil is God’s gift’) slogan that you have introduced?

When I was appointed Minister, I started to learn more about palm oil. I realised that palm oil, unlike competing oils, has many good qualities that warrant its status as the world’s leading vegetable oil. For example, its semi-solid characteristic at normal room temperature provides an effective solution to trans fats. It is highly versatile for various food applications. Palm oil is also nutritious and healthful as it is rich in potent antioxidants, Vitamin E and beta-carotene.

On the sustainability front, the oil palm is the most productive of oil crops, requiring the least acreage of land and inputs to produce the same tonnage of oil. There is also abundant and uninterrupted supply of palm oil for global consumption all year round. As such, I concluded that palm oil is a gift from God.

The slogan is an epitome of a product that has many attributes. It does not demean or belittle other commodities; it is an acknowledgement that palm oil is truly special. It is found in six out of 10 food and non-food products, and displayed on supermarket shelves in 160 countries. Can other commodities top that?

Finally, what are your wishes for Malaysian palm oil and the industry going forward?

Malaysia is one of the few net exporters of oils and fats. Therefore, it has a big role to play in helping to meet global food security. However, palm oil production is being linked to deforestation, carbon emissions, destruction of wildlife habitats, forced labour, violations of the rights of indigenous peoples, and food contamination. These claims are detrimental to the industry and can disrupt the global market access of palm oil.

Moving forward, I would like to see these issues being resolved for the benefit of all stakeholders. Here, we are addressing them through implementation of the MSPO standard; improved on-the-ground practices; and to some extent, branding. We also need to be more aggressive and effective in communications, and to work with concerned parties toward a common objective – the acceptance of sustainably produced palm oil.

By gofb-adm on Wednesday, July 1st, 2020 in Issue 2 - 2020, Cover Story No Comments

The global economy will look vastly different in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic, which has claimed over 200,000 lives worldwide at the time of writing. Many countries have unveiled stimulus packages to help keep their economies afloat. Malaysia is no exception, with its US$57 billion stimulus package – a substantial sum for an economy of its size.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Friday, February 21st, 2020 in Issue 1 - 2020, Cover Story No Comments

2020 is forecast to be a good year for palm oil in terms of a remunerative price for producing countries. Indonesia and Malaysia are the two biggest producers and exporters of palm oil globally. Other major producers are Thailand, Colombia, Nigeria, Guatemala, Honduras, Ecuador, Papua New Guinea, and Ghana.

Crude palm oil (CPO) prices have been on a rallying trend since October 2019, peaking above RM2,800 per tonne on Dec 9. Palm oil prices over the first nine months of 2019 were subdued because of persistent high stock, slower demand from major importers India and China, and the European Union’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED) II, which will phase out palm oil deemed unsustainable from its biofuel market by 2030. Differences between Malaysia and India in October were projected to further dampen sales and prices.

The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) organised the first Palm Oil Supply and Demand Outlook Conference (POSDOC) in Malaysia on Oct 22, 2019, to change the perspective of the market. As palm oil is a market-driven industry in many producing countries, CPOPC wanted all stakeholders to be cognizant of, and updated on, the supply, demand and price in the global market going into 2020. The market at the time was being fed with gloomy forecasts and a lack of informed data. The next few months will, therefore, be crucial for the industry to digest all the numbers and data going forward.

The focus of the conference was to develop a Supply and Demand Balancing Strategy to ensure that the market price is remunerative for the industry to remain sustainable. The industry needs to explore areas of mutual interest to work together, and to share common experiences to address problems as well as to optimise opportunities.

The conference was successful in providing a strategic platform for interaction and in-depth deliberation on three key aspects related to the palm oil industry, namely production supply, market demand and price outlook. The event enabled CPOPC to publicise the forecast supply and demand messages to sensitise the market. Palm oil prices have soared since then, and the upward trend is likely to continue as demand will increase due to a combination of factors including increased use of palm oil-based biodiesel and low production of palm oil in 2020.

The discussions at POSDOC were amplified at the International Palm Oil Conference in Bali, Indonesia, at the end of October. This gave another push to prices, extending the rally into November. Enthusiasm in the market was attributed to these factors:

1. The lengthy drought in Sumatera and Kalimantan early in 2019 resulted in many palm oil companies reducing fertiliser application, as the oil palm trees would not benefit much under extremely dry conditions. Additionally, due to persistent low palm oil prices over the year, companies decided to minimise their expenses by reducing manuring. This led to decreasing fruit production and eventually reduced palm oil supply.

2. Several analysts, including at the Globoil Conference held in Mumbai, India, in September, predicted that the palm oil price would be flat until the end of 2019 and in the first quarter of 2020. Discussions during Globoil also suggested that Indian importers would not buy palm oil from Malaysia, possibly to create an oversupply situation in Malaysia to cause a price collapse. As a result, Indian buyers started to buy from Indonesia. However, they unexpectedly lost their bargaining power in the duopoly market. Indonesia could not meet the sudden demand without raising the price. This also lifted the Malaysian price, but it was relatively lower, leading to further positive trends.

3. The bullish sentiment was also attributed to mandatory biodiesel programmes. It is well accepted that the recent price spike was due to Indonesia’s announcement to launch the 30% biodiesel blend (B30) programme in 2020. This will absorb over 9 million tonnes more CPO. Malaysia is preparing for B20 in 2020. When both volumes are combined, it will generate considerable CPO consumption. The anticipated scenario is that demand will outstrip supply, and the price will increase.

Most industry analysts have forecast that CPO prices will remain at elevated levels in 2020. Benchmark futures may average RM2,600 (US$628) a tonne, the highest in three years, according to the median of 25 estimates in a Bloomberg survey (Figure 1), versus an average of RM2,240 reported for 2019. Lower production in palm oil producing countries, increasing biodiesel mandates, and robust food demand will be the key price drivers in 2020.

Production outlook

Analysts are revising their outlook for production in Indonesia and Malaysia due to dry weather and lower fertiliser application. LMC International forecasts global palm oil stockpiles to reduce in 2020, as slow output growth coincides with a boost to biodiesel mandates. The relentless pressure from NGOs to stop oil palm planting, as well as the slowdown in new planting due to low prices earlier and a moratorium in Indonesia, will inevitably keep production growth low for the next few years.

Industry efforts to become more sustainable will become more crucial in 2020, to prevent more companies or countries restricting the use of palm oil. There are fears that the EU, which wants to phase out palm oil use in biofuel, may look to the food sector next.

CPOPC has advised producing countries that the EU’s proposed limits on 3-MCPD esters may impact palm oil use in food products and are set to be enforced legislatively to meet acceptable safety levels. CPOPC has agreed that a single maximum level of 3-MCPD at 2,500 µg/kg for all vegetable oils should be adopted, as the acceptable safety limit for consumption.

The national palm oil sustainable certification scheme in Malaysia will become mandatory for growers from 2020, even as producing countries continue working together to counter discriminatory measures. Weather calamities that affect soybean crops in the US and South America, or sunflower planting in the Black Sea countries, could also tighten supplies and support edible oil prices, including that of palm oil.

Demand outlook

The B30 biodiesel mandate in Indonesia is key to palm oil’s price direction. The policy will help increase CPO prices, improve industry competitiveness, and divert biodiesel to the domestic market. Nevertheless, biodiesel mandates in Indonesia and Malaysia are facing scrutiny, as palm oil trades at a large premium of almost US$100 a tonne to gasoil, compared to an average discount of US$54 over the past year. This will make palm oil more expensive to blend into biodiesel, and will require increased financial incentives. Indonesia has decided to re-impose export levies to fund the mandate starting from January 2020. Malaysia has announced the imposition of export duty from January 2020. Any failure to fulfil the mandate would not support palm oil prices.

The price rally has been so sudden that it threatens the traditional perception that palm oil is a ‘cheap’ vegetable oil for food and fuel. Palm oil hit parity with soybean oil for the first time since 2011, reducing its price competitiveness against other edible oils and prompting buyers to consider alternatives. While a political argument between Malaysia and India disappeared in November, the markets are still on the lookout to see whether India may increase import duties, which could affect palm oil purchases.

China, meanwhile, has increased its buying since July as African Swine Fever reduced its hog rearing industry and lowered domestic demand for soybean meal. The China National Grain and Oils Information Centre expects palm oil imports to reach a record 7 million tonnes in the year starting October to fill the gap.

Palm oil performance – Indonesia

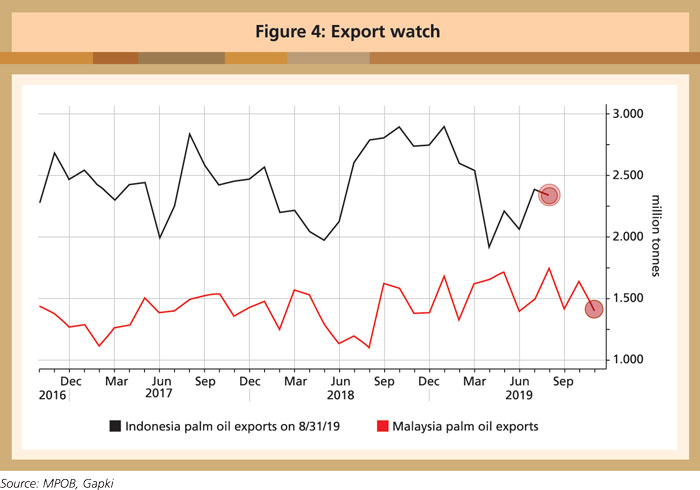

Palm oil is one of Indonesia’s top foreign exchange earners and contributes 1.5-2.5% to Gross Domestic Products (GDP). It directly and indirectly provides a livelihood for more than 16 million people. It is the second-biggest contributor to exports after coal. Palm oil contributed more than 9% to Indonesia’s total export value in 2018, lower than its contribution in 2017 of 11%. The main reason for the decline was the lower CPO price in 2018 compared to 2017. Low CPO prices continued into the first nine months of 2019.

As a consequence, Indonesia’s CPO export value declined 17.2% year-on-year (y-o-y) over the first nine months of 2019, greater than the 10.5% decrease over the same period in 2018. However, Indonesia’s CPO export volume in the January-September period grew 1.9% y-o-y, a reversal of the 1.9% contraction over the same period in 2018. This figure indicates that CPO demand remained strong in 2019, especially from China.

Indonesian palm oil faces serious challenges from its main importers, such as India and the EU. India has been reducing its dependence on the commodity and is shifting to local vegetable oils, such as rapeseed oil. The situation worsened for Indonesian palm oil when India imposed a lower import tariff for Malaysian refined palm oil up to September 2019.

The EU’s stance that Indonesian CPO is not environmentally friendly also threatens demand for the commodity from several countries. However, Trademap data show that the EU’s CPO import volume grew 8.2% y-o-y over the first seven months of 2019, despite the negative campaigns.

In order to promote sustainable palm oil and combat negative campaigns, Indonesia has maintained the moratorium on issuing permits for new oil palm plantations while enforcing sustainability standards through the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil certification programme.

Palm oil performance – Malaysia

Palm oil is still the best agri-commodity in Malaysia. The industry contributed 4.5% to the GDP and RM67.5 billion in export earnings in 2018. However, the export value declined because of the lower CPO price in 2018 compared to 2017. The low price continued into 2019. Based on the Malaysian Palm Oil Board average CPO price, the forecast for 2019 was RM2,120 per tonne, supported by a strong average of RM2,820 per tonne in December 2019.

Internally, CPO supply will likely decrease in 2020 due to lower production. The lower CPO price throughout 2019 has forced growers to reduce fertiliser applications, especially in plantations owned by smallholders whose productivity is lower than those owned by private companies. The lack of fertilisers will reduce production from the fourth quarter of 2019 up to 2021.

There was a report of drier weather and lower rainfall volume for 3-4 months in Pahang, Selangor and Perak in the first quarter of 2019 and Sabah in the third quarter. There will be fewer fresh fruit bunches (FFB) due to floral and bunch failure during the dry season; this will affect production in 2020. In November and December, several states in Peninsular Malaysia were flooded, and this may affect the harvesting and transportation of FFB.

CPO production will also be limited because there will be a small increase in the total plantation area this year. Malaysia has enforced new policies, such as the capping of the total oil palm cultivated area at 6.5 million ha; putting a stop to new planting of oil palm on peatland; banning the conversion of forest reserved areas for oil palm cultivation; and opening up oil palm plantation maps for public access.