The Pollination Story, Part 1

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Publication No Comments

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Publication No Comments

The Libuk Durian massacre was certainly the bloodiest event in the early history of Tungud. However the saddest incident, which took place the following year, must surely be the story of Suppiah and Leena.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Markets No Comments

Global oilseeds production for 2020/21 is forecast at 596 million tonnes, 750,000 tonnes above February. Higher Brazil soybean production, coupled with greater Australia and European Union (EU) rapeseed production, have more than offset lower palm kernel, cottonseed and sunflower seed production forecasts.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Markets No Comments

With a population of 211 million, Brazil is the largest country in South America and the largest economy in Latin America. Brazil is a leading oilseeds producer globally and one of the world’s largest producers of soybean oil. Strong international demand for its agricultural exports has been supported by the devaluation of the Real. This has also discouraged dollar-denominated imports and, in turn, stimulated demand for domestic agricultural products.

In 2019, Brazil’s production of oils and fats amounted to 11.4 million tonnes. Soybean oil made up 77% of this. Most of the oils and fats are consumed locally. According to Oil World, consumption of oils and fats in 2019 amounted to 10.9 million tonnes. Despite an economic slowdown as a result of the widespread effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, Brazil’s agricultural sector thrives, having entered new markets and set export records in recent months.

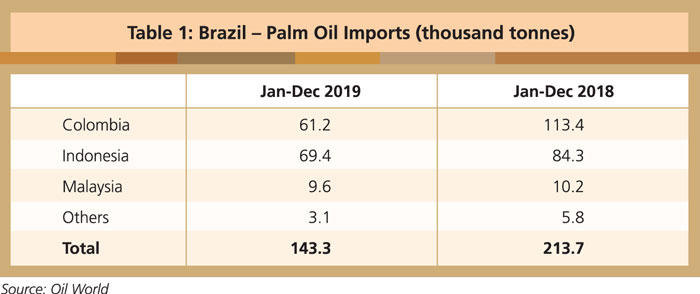

Brazil is a net importer of palm oil. National production of palm oil is insufficient to fulfill domestic consumption which reached 620,000 tonnes last year. In 2019, Brazil imported 143,000 tonnes of palm oil, mainly from Colombia and Indonesia (Table 1). Last year, Brazil was Malaysia’s sixth-largest export destination in the Americas region. Malaysia’s palm oil exports to Brazil consists mainly of RBD palm oil and RBD palm olein.

Palm oil is considered an economical alternative to other edible oils such as soybean oil and sunflower oil. Higher acceptance among food processors is expected to boost palm oil demand growth in Brazil.

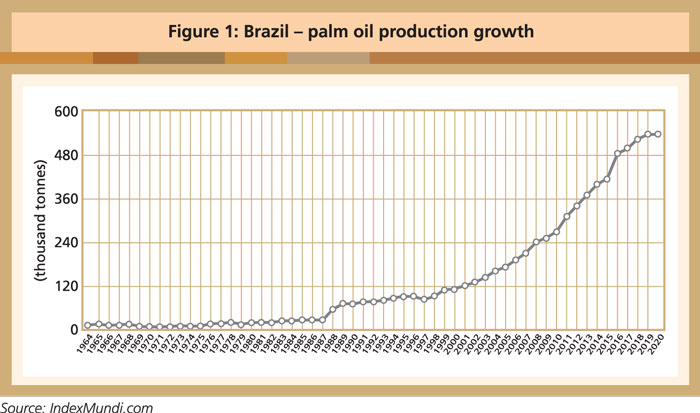

Over the last five years, palm oil production has grown marginally in Brazil. According to Oil World data, it amounted to about 470,000 tonnes in 2019, or roughly 4% of total oils and fats production. However, IndexMundi, a data portal that gathers facts and statistics from multiple sources, projected a higher production volume of palm oil in Brazil (Figure 1).

Brazil’s goals

The country began focusing aggressively on oil palm expansion initiatives in 2004. With 31 million ha of degraded land, Brazil is thought to be on track in achieving its objective of establishing itself as a major producer of palm oil. According to a report by Abrapalma, the body which represents palm oil producers in Brazil, the land area dedicated to oil palm doubled between 2004 and 2010. This is projected to double again between now and 2025.

Palm oil production is mostly limited to the Amazonian state of Pará, which offers an ideal climate throughout the year, as well as lower land prices. Despite industry growth of over 200% since its inception, oil palm cultivation only covered about 219,000 ha by 2014, or less than 1% of the more than 31 million ha of cleared land that is considered to be potentially available for this purpose.

One main reason for the slow expansion appears to be the inability of the plantations to produce palm oil at a competitive price. Brazil’s lack of an adequate transportation infrastructure is another setback.

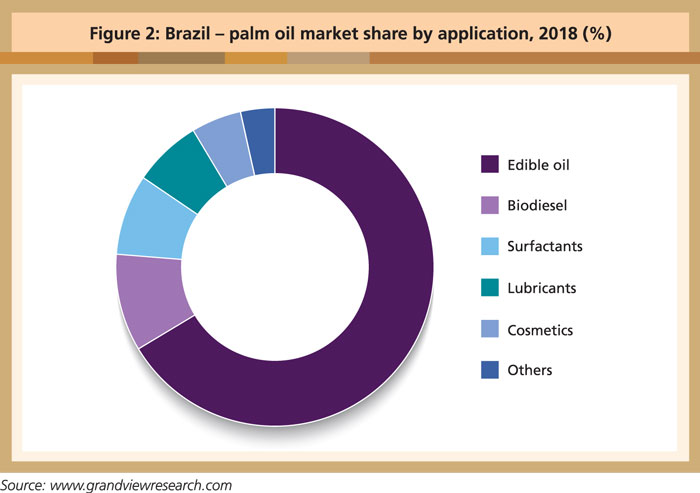

A recent report by the business intelligence firm Expert Market Research indicates that Brazil’s palm oil market was valued at US$938.4 million in 2019; it is projected to grow at a CAGR of 14.3% during the forecast period of 2020-25. The palm oil market size is expected to reach US$2.2 billion by 2025. The edible oils market segment accounted for the largest share of revenue, and is expected to continue its dominance in the coming years.

A significant increase in palm oil consumption – owing to the lower price and rising awareness of its health benefits – is expected to drive market growth. The food industry is a huge and fast-growing segment in Brazil. Its growth trend alone is expected to trigger demand for edible oils, including palm oil.

A report by Grand View Research highlights that CPO dominated Brazil’s palm oil market with a share of 56.5% in 2018 (Figure 2). The rising demand is closely associated with the demand growth from the food and beverage, personal car, cosmetics, detergent and biodiesel sectors.

Brazil’s palm oil industry is poised to continue its expansion. With strong government support, coupled with demand growth from the food and non-food sectors, Brazil is moving toward self-sufficiency within the next few years.

Zainuddin Hassan

MPOC USA

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Markets No Comments

The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic (Covid-19) at the beginning of 2020 had pushed China’s first-quarter GDP into its first decline in decades, contracting 6.8% year-on-year. However, the economy recovered from the second quarter, ending the year with a 2.3% year-on-year growth.

This bodes well for China’s oleochemicals industry which was affected by supply chain disruptions, price fluctuations of raw materials and lower profitability in 2020. The output of major oleochemicals – fatty acid, fatty alcohol, fatty amine and glycerin – amounted to 2.5 million tonnes in 2019. Fatty acid accounted for 72.7% of the total production volume in 2020, followed by fatty alcohol (11.6%), glycerin (10.2%) and fatty amine (5.6%).

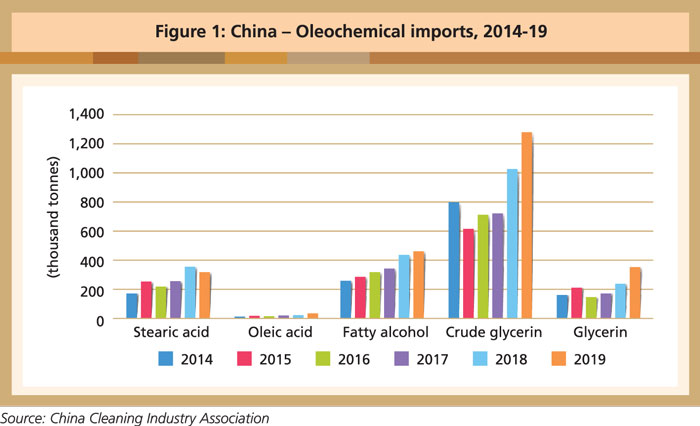

To meet rising demand, China imported 454,600 tonnes of fatty alcohol, 354,080 tonnes of fatty acid and 352,200 tonnes of glycerin in 2019. Favourable tax treatment for oleochemicals from ASEAN countries also encouraged imports (Figure 1).

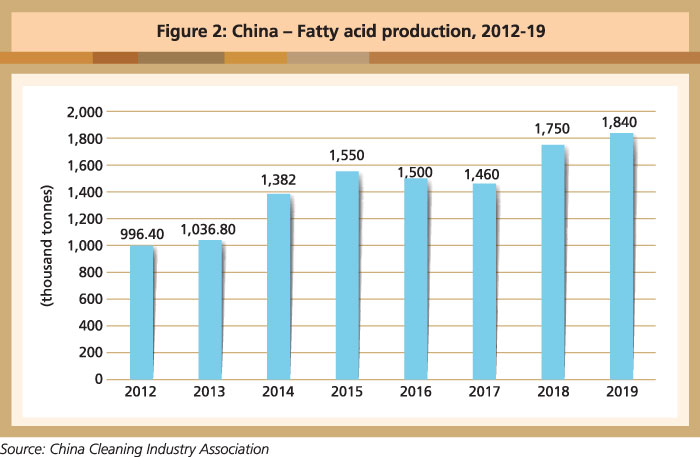

Fatty acid production recorded 1.8 million tonnes in 2019 (Figure 2), to which stearic acid contributed about 1 million tonnes with 276,500 tonnes of soap noodles and 300,000 tonnes of oleic acid being produced. China imported 319,000 tonnes of stearic acid in 2019, with Indonesia (260,000 tonnes) and Malaysia (57,000 tonnes) being the major suppliers. Oleic acid imports rose to 35,000 tonnes, or by 45%, to meet demand at a time when domestic production was flat.

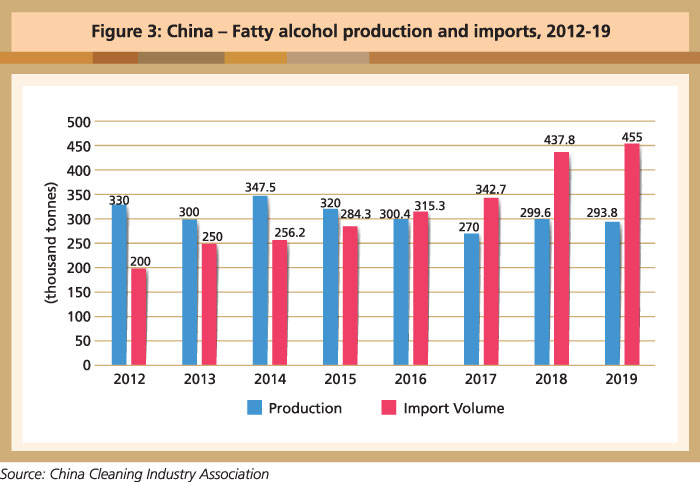

Fatty alcohol production was led by six domestic suppliers. However, capacity fell from 685,000 tonnes in 2015 to 655,000 tonnes in 2019. Output fell to 293,800 tonnes (by 1.9%) in 2019, from 299,600 tonnes in 2018. Against this scenario, demand went up steadily from 520,000 tonnes in 2015 to 650,000 tonnes in 2019.

Falling local production and rising demand led to a surge in imports (Figure 3). In 2019, China’s fatty alcohol imports stood at 455,000 tonnes, or 17,200 tonnes (3.9%) more than in 2018 (Figure 3). Indonesia (70%), Malaysia (25%), Thailand (4%), the Philippines and India were the main suppliers.

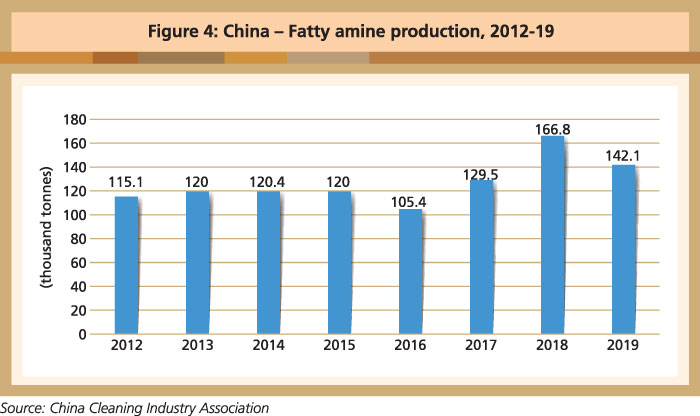

The China Cleaning Industry Association (CCIA) reported that 142,100 tonnes of fatty amine were produced in 2019 (Figure 4). Of this, primary fatty amine accounted for 49,400 tonnes (34.8%).

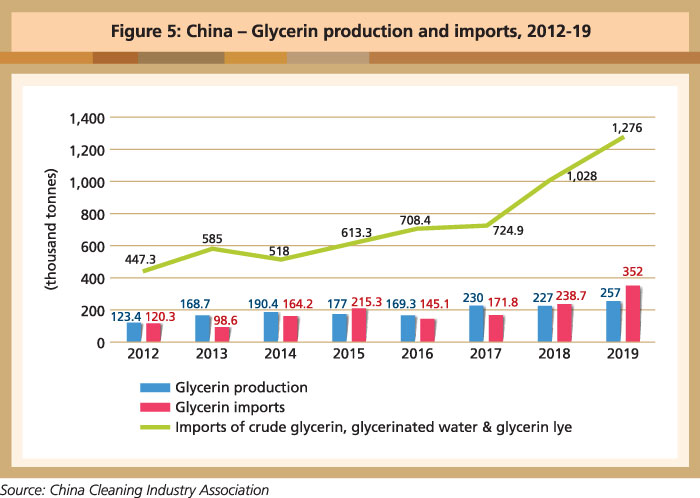

Domestic glycerin output for industrial and medical use and for special oils and fats registered 257,300 tonnes in 2019 (Figure 5), up by 13.6% against 2018. Imports reached 352,200 tonnes in 2019, or higher by 47.5%. Crude glycerin, glycerinated water and glycerin lye imports amounted to 1.3 million tonnes, up by 24% over the same period. Crude glycerin from Indonesia, Brazil, Argentina and Malaysia made up 74% of this.

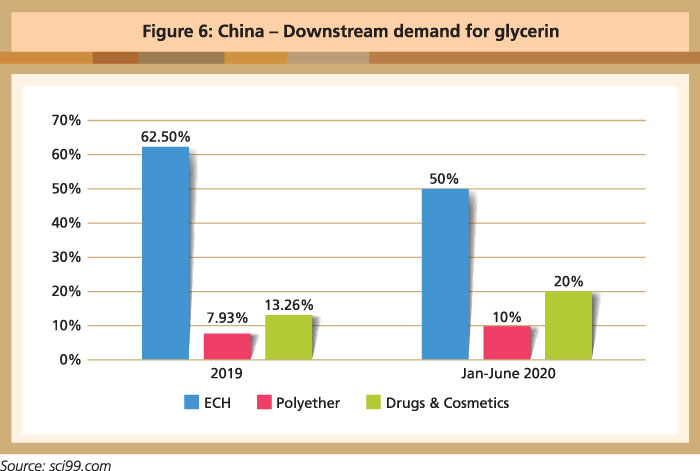

Three downstream sectors – Epichlorohydrin (ECH, at 62.5%), polyether (7.9%) and drugs and cosmetics (13.3%) – absorbed more than 80% of the glycerin volume in 2019. In the first six months of 2020, these sectors respectively accounted for 50%, 10% and 20% of glycerin demand (Figure 6).

In relation to the oleochemicals sector, China imported 11.5 million tonnes of edible oils and 1.2 million tonnes of oils for industrial non-food use in 2019. According to the China National Grain & Oils Information Centre, vegetable oil consumption is expected to decline by 810,000 tonnes in 2019/20 for the first time in recent years, due to the impact of Covid-19.

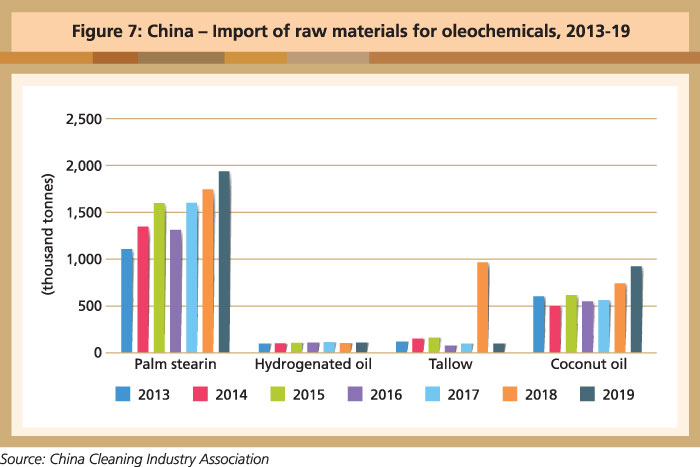

Demand is projected to fall by 180,000 tonnes for direct edible oils, and by 630,000 tonnes for non-food industry use. Imports of palm stearin, palm kernel oil and coconut oil experienced growth in 2019, compared to 2018 (Figure 7). Palm kernel oil saw the largest increase of 24.9% among the raw materials for oleochemicals, due to stable output in Indonesia and Malaysia.

Price trends

Stearic acid

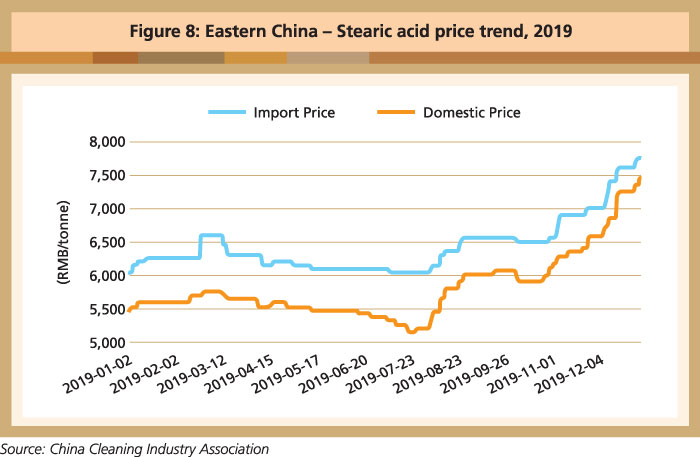

In eastern China, the price of imported stearic acid peaked at RMB7,750/tonne over the course of 2019. The highest price for domestic first-grade stearic acid price was RMB7,500/tonne (Figure 8).

Fatty alcohol

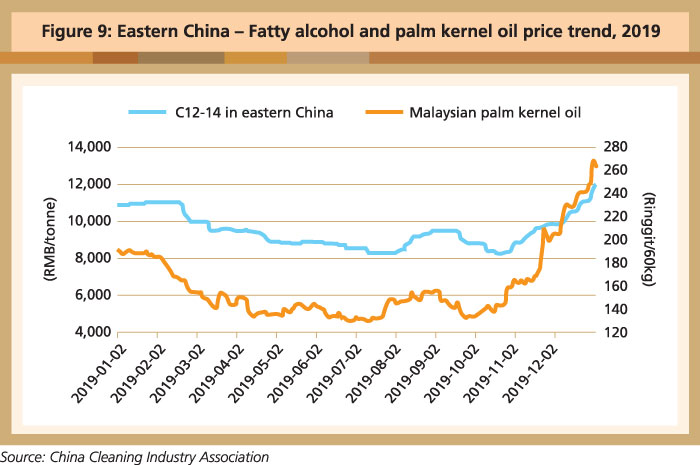

The C12-14 fatty alcohol price trend mirrored that of its raw material – palm kernel oil – in 2019 (Figure 9). The fatty alcohol price fell from March and bottomed out at RMB8,200/tonne in July. Subsequently, the traditional peak season for detergent and cosmetics production supported the price from August. It went up to RMB12,000/tonne in eastern China by the end of 2019.

Fatty amine

The price of fatty amine trended downwards in 2019. Dodecyl tertiary amine and tetradecyl amine stood at RMB19,000/tonne at the beginning of 2019, falling by 24% to RMB14,500/tonne at the end of July. Over the next four months, the price stabilised at RMB14,000/tonne, and then went up to RMB15,000/tonne by the end of 2019.

The average price of dodecyl tertiary amine and tetradecyl amine was RMB15,300/tonne in 2019, down by 26.4% against 2018 – it was the largest decline in recent years. The price of fatty primary amine was about RMB14,000/tonne for the first seven months. It fell to RMB13,500/tonne in August and rebounded to RMB14,650/tonne at the end of 2019.

Glycerin

Crude glycerin and refined glycerin are the two main products in this category. Crude glycerin, as a by-product of fatty acid, contributes an annual output of 300,000 tonnes in China. The supply of refined glycerin is almost entirely dependent on imports, and is refined from crude glycerin.

The price of refined glycerin registered RMB3,400/tonne in eastern China by the end of 2019, down by 15% from the beginning of the year. The price fell to its lowest at RMB2,900/tonne from the end of June and into the middle of July. The highest price of RMB4,150/tonne was recorded in January and February.

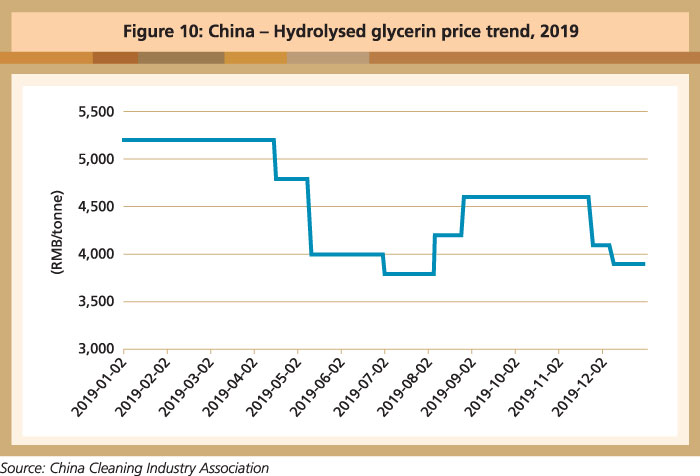

The price of 99.5% hydrolysed glycerin decreased 26% from RMB5,200/tonne at the beginning of 2019 to RMB3,900/tonne at the end of the year (Figure 10).

Outlook for China’s oleochemicals industry

Covid-19 lockdowns have generally had a serious impact on the global economy. While China has reported a better- than-expected performance since the second quarter of 2020, some uncertainties remain in its oleochemicals industry. Development of the sector will depend on both the internal and external environment, encompassing policy implementation, downstream demand, imports and effective control of the pandemic.

The implementation of biodiesel mandates in Southeast Asia and South America will have an impact on China’s glycerin output. The price of palm oil will influence the progress of biodiesel programmes in Southeast Asia, as well as the import and export of glycerin products. The palm oil market itself will be affected by the weather and any natural disasters.

China has raised its imports of refined glycerin, mainly from South America, despite oversupply in the domestic market. Imports increased by 29% to 177,080 tonnes over the first five months of 2020, compared to 136,930 tonnes in 2019. This has squeezed the domestic refined glycerin market and put pressure on the overall glycerin price.

The ECH, daily chemical and paint sectors are major downstream consumers of glycerin in China. The newly-enlarged capacity in domestic glycerin production will largely be absorbed by the ECH sector, thanks to its good profit margin and because it is environment-friendly. The annual production capacity of ECH will stay at 600,000 tonnes.

There is increasing demand for alcohol-based hand sanitisers to control the spread of Covid-19, thereby enhancing demand for glycerin as well. Meanwhile, glycerin consumption in the paint sector is likely to decline due to reduced construction of buildings during the pandemic.

The fatty alcohol sector will be affected by the macro-economic situation, palm oil market and downstream demand, but there is room for optimism with the return to economic growth in China.

Fatty alcohol use is split between higher alcohols, medium alcohols and lower alcohols. Demand for higher alcohols is limited as it is mainly applied in textiles, creams and lotions, all of which have taken a big hit from the pandemic. There is weak demand for lower alcohols as well. However, the downstream sectors of medium alcohols are the cleaning industry and tertiary amine sector, which contribute significantly to controlling the spread of Covid-19.

Desmond Ng

Regional Manager

MPOC China

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Markets No Comments

Egypt’s geographical and cultural proximity to its main export markets – including the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and European countries – facilitates business operations and trade. Egypt further has the advantage of a strategic location at the crossroads of MENA, Europe and Asia, making it the centre of trade and business in the Middle East.

It is also party to several preferential trade agreements that offer tariff reductions and rules of origin for products. Notably, it has access to Europe, Arab countries and Sub-Saharan Africa through the Egypt-European Union Partnership Agreement; the Greater Arab Free Trade Area; and the Common Market Eastern and Southern Africa Agreement (COMESA).

To boost trade with its neighbours, Egypt is building a rail link between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea ports as an alternate route to the Suez Canal. Apart from cutting down transportation time, the link could serve as the nucleus of an aspiring rail connection between North Africa and the Arab Peninsula. This project is under development until 2021.

The Adabiya port is the only one in Egypt that can receive bulk palm oil and coconut oil shipments. Storage tanks are equipped with heaters to suit tropical oils and maintain their quality. Availability of storage tanks is affected, though, by growing demand for palm oil and the port’s role as a redistribution hub.

The port currently has 91 tanks and 207,200 tonnes of storage capacity. All the tanks are either owned or held under a long-term lease. The biggest owners are Integrated Oil Industries with 33,000 tonnes of capacity; United Oil Processing Company (26,000 tonnes); and Afia International (22,500 tonnes). However, several companies are willing to rent out part of their facilities to new entrants.

DP World Sokhna port was established under the build-operate-transfer system, near the entrance to the Suez Canal. Its position on the Red Sea in Egypt allows it to handle cargo transiting through one of the world’s busiest commercial waterways.

An established road and rail network makes the port perfectly placed to reach Cairo’s 18 million consumers. Roads have been constructed through the port area. Specific conveyor systems help minimise the cost of logistics and reduce the environmental impact. Utility supplies like water, electricity, telecommunications and IT facilities are provided.

Current facilities include a container terminal, general cargo/Ro-Ro terminal, bulk terminal and a livestock terminal. However, the port is not ready to receive liquid bulk palm oil as there are no storage tanks with heating facilities. Construction of a second basin, together with a jetty and liquid bulk facilities, is well underway. Specialist warehousing is also being built to support industries located outside the port.

Market-related challenges

A consumer population of about 196 million in North Africa – covering Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco – has created a large market for oils and fats. Adequate infrastructure, a higher standard of living and rising vegetable oil consumption will improve palm oil uptake.

In 2020, the consumption of vegetable oils and fats registered 2.4 million tonnes in Egypt; just over 1 million tonnes in Algeria; 0.8 million tonnes in Morocco; and 0.4 million tonnes in Tunisia. However, domestic production can only supply up to 34% of needs. While imports are required to satisfy demand, Malaysian Palm Oil (MPO) will have to address several challenges to improve its market share.

Indonesia’s palm oil price discount has severely affected MPO imports. In 2020, Egypt imported over 1 million tonnes of palm oil, with 85% of this from Indonesia. The main buyers, who bring in more than 80% of the palm oil products, are ARMA, SAVOLA, IFFCO, United Oil, Gulf Arabian, El Safwa, PIL and Wilmar.

Egypt is a highly price-sensitive market. MPO exporters should therefore strategise by forming joint ventures with local oils and fats manufacturers to reduce operational costs; utilise available market networks and distribution channels; and leverage on trade agreements to which Egypt is party.

Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco now levy high import duty and value added tax (VAT) on direct imports from Malaysia (Tables 1-3). This hampers trade, as the MPO price is much higher than that of other soft oils.

Advantages of trade agreements

Egypt has strong potential as a hub for commercial activities in Africa and the Middle East, due to the favourable duty-free structure for imports of palm oil products, including semi-refined and fully refined oils. Trade agreements provide Egypt with another edge in penetrating the market in neighbouring countries.

In 2020, the palm oil market share in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia was only 14%, 6% and 25% respectively. Hence, there is much room for expansion. These countries could potentially import an additional 744,000 tonnes of palm oil, which could then attain a market share of 52% as in Egypt; and an extra 332,000 tonnes for a 30% share (Table 4). With the population increase and heightened awareness of palm oil, demand could penetrate neighbouring countries as well. However, a better effort will be required to grasp the opportunities.

Agadir Free Trade Agreement

This has established a free trade area between Jordan, Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia and other Arab countries of the Mediterranean area. It is also part of the free trade Euro-Mediterranean area as foreseen by the Barcelona Declaration.

The Agreement deals with important issues such as customs systems, rules of origin, government procurements, financial transactions, safeguard measures, new industries, subsidy and dumping, intellectual property, standards and specifications, and establishing a dispute settlement mechanism.

Rules of origin constitute an essential article, since this will increase the prospective European Market Access for products from party states. In turn, this will encourage investments and increase inter-country cooperation. Under the Agreement, all industrial and agriculture products are exempted from most of the tariff and non-tariff measures.

Pan Arab Free Trade Agreement (PAFTA)

PAFTA covers trade for Egypt, Bahrain, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Syria, Sudan, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen. Member-states of the Arab League that have not yet completed the entry procedures are Djibouti, Comoros Islands, Mauritania and Somalia.

PAFTA was established by the Arab League’s Economic Council to favour economic and trade relations between the Arab states and the rest of the world. It is the first concrete step towards creating an Arab economic bloc that creates value to the world.

COMESA

COMESA involves Angola, Burundi, Comoros Islands, DR Congo, Sudan, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia, Rwanda, Seychelles, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Egypt signed the Agreement in 1998. It grants full customs exemptions for exchanged imports, provided that certificates of origin accompany the products.

The EU-North Africa trade agreements

The trade agreements between the European Union and Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco are part of a broader effort to cover the North Africa market. However, economic growth in the four countries has been relatively slow, volatile and challenged by fiscal imbalances for the last 10 years.

Mohamad Suhaili

Market Analyst, MPOC

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Markets No Comments

The struggle to survive the Covid-19 pandemic shows how the world is just one big village. We share different values, cultures and political views and we also draw political boundaries to separate one country from another.

But the pandemic has shown us that what we do as a community will affect others. Thus, quoting [Indonesian] Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi’s remarks at the Annual Press Statement [on Jan 6], we need to recover stronger together to achieve a global recovery.

The European Union’s (EU’s) discriminatory policies and regulations on palm oil have hurt economic and political ties between the bloc and ASEAN’s palm oil producing countries. Considering the importance of these ties toward mutual recovery, it is imperative that the two sides come to the negotiation table with clean slates and an honest intent to work hand-in-hand.

The EU, for its part, must acknowledge the credible and scientifically proven claims that palm oil is one of the best choices available. Productivity is just one example. On the other hand, palm oil producing countries in ASEAN need to take into account the EU’s concern about the loss of tropical wetlands and forests in Southeast Asia.

Thus, the formation of a joint working group (JWG) on vegetable oils that came about from the EU-ASEAN Ministerial Meeting [in December 2020] is a fresh opportunity to have mutual contributions and find solutions to the global village’s challenges.

The loss of forests in the tropics over the past three decades cannot be denied, as developing countries strode toward development and self-reliance. What is clearly deniable are arguments that blame the deforestation on the palm oil industry. Furthermore, oil palm plantations have been [linked] to forest fires and the extinction of orang utan.

As the palm oil industry matured over the past decade, the focus has been placed on protecting the overall landscape, not just for palm oil but for all forest products. In fact, Indonesia is the eighth-largest contributor of the world’s tree canopies and a prominent actor behind the initiatives to protect high conservation value (HCV) or high carbon stock areas to preserve the endemic fauna and flora.

The palm oil industry has shown remarkable achievements. It, for example, has elevated millions of people from poverty, created jobs and generated revenue that has improved development. All that happened without land expansion. The fact that the Indonesian government has enforced a land expansion moratorium for oil palm plantations deserves applause.

Global norm?

The EU has long been viewed as an antagonist by palm oil producing countries. It is essential for the EU to acknowledge that countries like Indonesia have made efforts to produce sustainable palm oil, as evident in the sustainable certification known as ISPO [Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil]. It is also noteworthy that the Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries intends to start a study on principles of sustainable palm oil that could form a framework to cover all vegetable oils.

The fact that the EU is the most eco-conscious market and is willing to pay premium prices for sustainable vegetable oil needs to be taken into account, and there is no better venue for this to happen than at the JWG. The rhetoric that has painted palm oil black will therefore be cleared once the EU acknowledges the capability of ASEAN palm oil producing countries in fostering sustainable development and fulfilling the premium market.

This mutual understanding will indeed be key to the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which have guided palm oil producing countries’ commitment to sustainability. After all, a holistic approach to the environment and the SDGs is part of the ASEAN-EU consensus.

Even further, should the EU and ASEAN find agreement on this, a UN General Assembly resolution could easily make it a truly global norm for all vegetable oils. In the meantime, any earlier decisions on palm oil must be shelved as the EU and ASEAN countries look to build back better.

The devastated global economies resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic should be rehabilitated using a proper approach. The commitments made by nations and global corporations to free us from fossil fuels must be supported by a readily available solution. Palm oil’s contributions to global emissions or biodiversity loss is minor when compared to the overall emissions of developed countries.

Palm oil producing countries have repeatedly shown that they are up to the challenge of reducing the industrial impacts. From protecting HCV areas to the reduction of emissions in industry operations, no other commodity has such a high level of support from governments, civil society and environmental groups.

If banning palm oil is the EU’s option, will it be willing to accept millions of palm oil farmers as migrants? Therefore, failure is not an option. The JWG is a litmus test for the EU and ASEAN to deliver the solutions needed to the problems and to deliver them in time.

Responding to Minister Retno’s call for recovering stronger and together, producing countries must strive to make palm oil the most sustainable vegetable oil on earth. [At the same time] all vegetable oils should be given space to feed the world. One condition should be met: all oils are answerable to one standard, including reducing their ecological impact, whether it be for food or fuel.

Source: The Jakarta Post,

Jan 22, 2021

This is a slightly edited version of the article, which is available at: https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2021/01/21/global-recovery-needs-fresh-approach-to-eu-asean-relations.html

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Markets No Comments

The prestigious European think tank, the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, has published a policy paper which has direct relevance to European strategy towards palm oil and broader European Union (EU) relations with Malaysia.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Sustainability No Comments

The palm oil industry has become a major contributor to the economies of Indonesia and Malaysia over the past few years. In Indonesia alone, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics, 48.4 million tonnes of palm oil were produced in 2019, approximately 60% of the world’s supply. More than 60% of the palm oil was exported, valued at almost US$16 billion.

Further, according to the Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs, the expansion of oil palm plantations has helped lift more than 10 million Indonesians out of poverty since 2000. The industry supported the livelihoods of 23 million people in 2018, 4.6 million of whom are involved in independent smallholdings across the country.

However, along with other agricultural commodities, such as rubber, soybean, coffee and cocoa, palm oil production has been linked to legal and illegal deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss, greenhouse gas emissions, and violations of labour and community rights. Consuming countries as importers of ‘forest risk commodities’ have frequently been held responsible for driving these impacts and for importing deforestation through commodity supply chains.

Stakeholders along the supply chain have responded via various means, including through policy measures to reduce deforestation, forest degradation and associated emissions. As an example, through its second Renewable Energy Directive (RED II), the European Union (EU) plans to phase out eligibility of biofuel feedstock to EU renewable energy targets where they are assessed to be the cause of high indirect land use change.

Palm oil is currently classified in this category and since around half of the EU’s palm oil imports are for biofuel, the regulation could affect a significant proportion of palm oil exports to the EU from Indonesia. The Indonesian government is currently challenging the RED II in the World Trade Organisation.

Indeed, in recent years, importing countries, consumers and NGOs have been pressuring palm oil companies and producing countries, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, to step up their sustainability game. Many stakeholders have responded with efforts to show that a sustainable palm oil industry, which provides win-win outcomes for markets and the environment, is not only possible but also constitutes the ambition moving forward.

The Indonesian government, for example, has accelerated the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification in the past couple of years. In addition, the government has issued a national action plan for sustainable palm oil and adopted a moratorium policy banning new expansion of oil palm plantations. Based on an analysis by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Indonesia’s total deforestation fell by 20% following the launch of the moratorium policy in 2011.

Subnational jurisdictions at the forefront

In Indonesia, some subnational governments have been very active in supporting the national government’s policies on sustainable palm oil. According to the Civil Society Coalition for Improving Palm Oil Governance, up to December 2019, six provinces and eight districts have responded positively to the national government’s policies by issuing bylaws or making public commitments about the moratorium.

A few subnational governments have also been embracing the jurisdictional approach, which seeks to address palm oil and deforestation related issues at the subnational level by involving all relevant stakeholders. For example, Seruyan District in Central Kalimantan is working with the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to ensure all palm oil producers in the district comply with RSPO Principles & Criteria.

This approach is also pursued by the state of Sabah in Malaysia, which aims to be 100% RSPO certified by 2025. In East Kalimantan, the Berau District Government is collaborating with the Nature Conservancy, Climate Policy Initiative, and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit on a low-emission oil palm development programme. In North Sumatra, the South Tapanuli District Government is collaborating with the United Nations Development Programme and Conservation International Indonesia to form a multi-stakeholder forum on sustainable palm oil.

These subnational initiatives, led by the provincial/state and district-level governments, hinge on the role local governments can play given their authority and legitimacy to promulgate regulations and policies for sustainability. The subnational governments, for example, have the authority to issue certain permits on the use of land and establishment of plantations, and to monitor and enforce laws and regulations underpinning the transition of the entire jurisdiction towards sustainability.

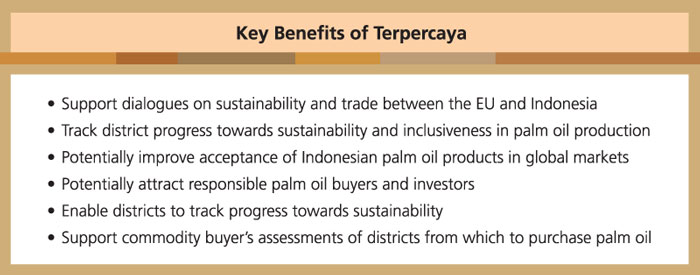

Further, the subnational initiatives can potentially bring in multiple benefits – not only by attracting palm oil buyers and investors who care about sustainability, but also by supporting national and subnational governments in making progress towards development targets and international commitments, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement.

Tracking jurisdictional sustainability

With support from the EU, the Indonesian Ministry of National Development Planning (Bappenas), which coordinates the planning and monitoring of the nation’s development and SDG implementation, is spearheading an initiative to implement a framework to monitor and measure the performance of districts in achieving national priorities and the SDGs.

The framework resulted from an initial 2018-19 study, led by the European Forest Institute (EFI) and the Indonesian NGO Inobu, which assessed the feasibility of mapping and screening Indonesian districts based on their commitment and performance regarding sustainability of forest and agricultural production, especially palm oil.

The framework, known as the Terpercaya approach, takes its name from an Indonesian word meaning ‘trustworthy’, as it aims to generate objective and transparent information and analysis. Through a collaborative process involving the multi-stakeholder Terpercaya Advisory Committee, composed of the government, private sector and civil society stakeholders, the initial Terpercaya study developed 22 indicators.

The indicators, covering environmental, social, economic and governance aspects, are based on Indonesian laws and regulations, aligned with national priorities and the SDGs, and supportive of the national policies to promote a sustainable palm oil industry, such as the ISPO standard.

By covering entire districts, the Terpercaya approach should help create a level playing field for all producers, including certified and non-certified actors, companies with and without sustainability commitments, and smallholders of all types.

The approach will be particularly advantageous to smallholders, as it provides them with the chance to better access the markets for sustainably produced palm oil. At a broader scale, the Terpercaya approach should also assist the districts’ efforts to increase competitiveness and attract sustainable, green investment.

Terpercaya data platform

In 2020, Bappenas, EFI, Inobu and several other partner organisations collected data for the 22 agreed indicators and established a national database containing information on the sustainability of Indonesian districts.

A user-friendly public Terpercaya data platform showcasing this information will be launched soon. It will monitor and measure sustainability progress against baseline data and allow users to compare district progress in various dimensions of sustainability. Linking the platform to supply chain information to help commodity buyers assess districts from which they are purchasing palm oil will also be possible.

The platform will benefit different users. At the subnational level, the platform will enable district authorities to track progress towards sustainability and inclusiveness in palm oil production. For example, it could encourage district authorities to resolve land tenure issues and accelerate ISPO certification for smallholders, thus complementing existing commodity-based certification systems.

At the same time, the central government can use the monitoring system to programme incentives and support for local governments to achieve sustainable and inclusive agricultural development and SDGs. In this context, Bappenas plans to use the Terpercaya framework to guide fiscal transfers to districts under the special allocation fund for agriculture.

Further, the Terpercaya platform could help improve acceptance of Indonesian palm oil products in global markets and ensure that civil society, consumer countries, investors and commodity buyers are well informed about the progress made by Indonesian districts. The Terpercaya platform could also serve to contribute to constructive and open dialogue.

The Terpercaya platform could additionally support the private sector in meeting their sustainability commitments. For example, international buyers of palm oil and investors could use the information presented in their sustainability due diligence assessment, to help determine with which districts to interact.

At its core, the Terpercaya approach aims to help resolve trade-offs between palm oil production and environmental protection by promoting market access for sustainable palm oil, utilising government capacity, and supporting broad-scale achievement of national priorities and internationally agreed SDGs.

The approach’s unique selling points include the objective information it showcases, the collaborative development of indicators, and its alignment with the national context, especially the existing policy and legal frameworks. In principle, such an approach could be easily implemented in countries other than Indonesia.

For now, the primary focus is to build a larger and stronger collaboration around Terpercaya, involving a broader range of stakeholders in Indonesia and beyond. This is needed to ensure that the approach reaches its maximum potential in advancing sustainability in the palm oil industry and maintaining benefits from production and trade of a valuable commodity.

In this context, the recently initiated EU-funded Keberlanjutan sAwit Malaysia dan Indonesia (KAMI) or ‘sustainability of Malaysian and Indonesian palm oil’ project aims to support policy dialogue between relevant stakeholders in the EU, Indonesia and Malaysia on the sustainable use of palm oil.

The project also encompasses support for collection and dissemination of agreed, objective information on subnational level sustainability performance to reinforce dialogue and better communicate on the production of palm oil.

Through KAMI, support for Terpercaya will continue and experience gained over past years will be built upon in developing jurisdictional indicators of sustainability performance aligned to EU policy. Through collection and dissemination of associated information, Terpercaya will transition from a national to an international approach.

Satrio Wicaksono

Forest and Land Use Governance Expert, EFI

Anang Noegroho

Director of Food and Agriculture

Ministry of National Development Planning, Indonesia

Silvia Irawan

Executive Director, Inobu

Josi Khatarina

Senior Advisor, Inobu

Jeremy Broadhead

KAMI Project Manager, EFI

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Sustainability No Comments

Malaysia has succeeded in uplifting the lives of people in rural communities through oil palm cultivation. It has also put in place legal, financial, environmental and social measures to ensure that production of its palm oil meets the principles and criteria of sustainable palm oil, under the framework of a national certification scheme.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Cover Story No Comments

Even the most well-intentioned efforts can go awry. Policies meant to accomplish one outcome, or prevent another, sometimes have unforeseen effects. The European Union (EU) is not exempt.

Read more »