Brazil Agriculture Seeks Remedies…

By gofb-adm on Sunday, May 1st, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Markets No Comments

By gofb-adm on Sunday, May 1st, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Markets No Comments

Brazil is a powerhouse agricultural producer, ranking among the top three global exporters for a host of commodities. To support its massive agribusiness sector, Brazil relies on imported inputs, including fertilisers. Annually, Brazil imports over 80% of its total fertiliser needs. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has substantially elevated the risk of disruption to the global fertiliser trade. In Brazil, there is rising concern that growers may not be able to expand the crop planted area in the 2022/23 season.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, May 1st, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Environment No Comments

2021 was a significant year in terms of climate change. Extreme weather patterns, floods and droughts alike shook the world. A ground-breaking report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) moved the United Nations Secretary General to describe the year as “a code red for humanity”.

We saw world leaders coming together to address climate change with the US joining the all-important Paris Agreement; the environment ministers of G7 countries renewing their climate agreement; and NATO, the world’s most powerful defence alliance, discussing climate change for the first time at its Leaders’ Summit.

These efforts resulted in major commitments being made towards protecting wildlife and the environment, including a ban on the use of plastic; steps against the use of fossil fuels; and intentions expressed to achieve net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) as soon as possible and by 2050 at the latest.

Despite moves in the right direction, the G20’s 2021 Climate Transparency Report published in October told another story altogether. It stated that the world’s richest nations, responsible for around 75% of global GHG emissions, are still not on track to limit global warming, despite raising ambitions.

EU ambitions

The European Union (EU), a significant contributor to carbon emissions and an important global player in the fight against climate change, rolled out ambitious plans in 2021. In June, it issued the European Climate Law, as part of the European Green Deal, for Europe to become climate neutral by 2050.

Under this, intermediate targets were set to reduce net GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030 – this is known as the ‘Fit for 55’ package and includes provisions for a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

Also released as part of the package was the revised Renewable Energy Directive, which bans the use of palm oil and talks about using sunflower oil as an alternate biofuel which is produced in Europe. The reason stated for the ban on palm oil is that it ‘contributes to extensive deforestation in Indonesia and Malaysia’.

The initiative, though, ignores the impact on vulnerable communities in developing countries. The upcoming ban on palm oil will affect the livelihood of thousands of smallholders, who make up a substantial percentage of producers.

It also disregards the high productivity of the oil palm, which produces more oil per hectare than other vegetable oil crops. As per the 2018 study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the oil palm produces up to nine times more oil per unit area than other major oil crops. Palm oil, the report says, produces 36% of food oil globally on just 8.6% of the land dedicated to food oil production. Rapeseed produces four to 10 times less oil than palm oil per unit of land and requires the use of more fertilisers and pesticides. More than that, it stores less CO2 than palm oil.

The answer to finding a balance between the needs of palm oil producers and the protection of forests may lie in a proposal by the European Commission. Published in November 2021, the ‘Proposal for a regulation on deforestation-free products’ acknowledges for the first time that voluntary schemes have been ineffective in achieving the required outcomes; it also strongly supports legally-binding certification of commodity crops as an effective policy measure to curb deforestation.

Both pre-regulation impact assessment and public consultations – which received nearly 1.2 million responses from stakeholders – showed clear support for legally-binding measures, including mandatory public certification schemes.

Malaysia is already ahead of the game in this regard. In 2015, it launched the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) standard, a national certification scheme that is enforced by the government for sustainable oil palm cultivation and palm oil production. It has since been made mandatory.

The MSPO has achieved commendable outcomes in guaranteeing that the palm oil produced is sustainable across the supply chain, with 93% of all the sector having achieved certification to date. In addition, Malaysia has reduced deforestation levels for four consecutive years. But the question remains: When will the EU pay heed to this?

Deforestation and global food systems

Another area that received attention in 2021 was deforestation and global food systems. At the end of 2021, the IPCC Working Group I report, ‘Climate Change 2021: the Physical Science Basis’ was published; it highlights that global temperatures will likely rise 1.5 degrees Celsius by around 2030.

The UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) was held in Glasgow from October to November 2021, with a worldwide focus on the same goals and priorities. Leaders from 110 nations signed a pledge to eliminate deforestation by 2030.

It also focused on the need to limit investments in contributing projects, and to implement restrictions against tree removal to make room for animal grazing and growing of crops like soybean, cocoa and oil palm.

The Forest, Agriculture and Commodity Trade Dialogue, held ahead of COP26, brought together the largest producers and consumers of internationally traded agricultural commodities (such as palm oil, soybean, cocoa, beef and timber) to promote trade and development, while simultaneously acting to protect forests and other ecosystems.

Additionally, global food systems – and their relationship to climate change – received a new level of attention in 2021. It became a major topic of discussion in light of several significant new government commitments at COP26. The UN Secretary- General’s Food Systems Summit, which took place during the General Assembly in September, featured food and agriculture both as a sector heavily affected by the climate crisis and as a major source of GHG emissions.

As global attention to food and climate issues grows, farmers – especially smallholders in the poorest countries – will need much more attention and support to weather the challenges they face on the front lines of the climate crisis in 2022. The battle against climate change is a global priority and would best be solved through cooperation and partnership.

Taking the pledges made at COP26 forward, increased collaboration is required between palm oil producing countries and buyers to ensure that global markets reward practices that promote sustainability and disincentivise damaging practices. The need is that the commitments made throughout 2021 are translated into legislative action within 2022-23, with transparency, accountability and involvement of indigenous peoples and local communities from the Global South particularly.

The main development to monitor in 2022 will be IPCC’s sixth assessment cycle with its three reports – these will contain the most up-to-date scientific assessment on the impacts of climate change and its potential solutions. Its results will deeply influence and help shape the global climate conversation toward COP27.

While 2021 was full of studies, reports, policies and promises around climate change, not all were fulfilled or paid heed to. Progress in 2022 will, among other things, depend on greater North-South collaboration and sincere partnerships.

Centre for Sustainable Palm Oil Studies

This is an edited version of the article which is available at:

https://thecspo.org/2021-in-review-global-environmental-developments-future-of-palm-oil/

By gofb-adm on Sunday, May 1st, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Sustainability No Comments

The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) has developed and launched the Global Framework Principles of Sustainable Palm Oil (GFP-SPO), which aims to provide a common language across different certification schemes being applied to palm oil production. It is anchored in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as its base.

The framework can also be used to value the contribution of palm oil toward achieving sustainable development in all producing countries, and to lay the foundations for the establishment of sustainability of a vegetable oils platform. This important document was adopted and approved by Ministers of CPOPC member-countries at their 9th Ministerial Meeting on Dec 4, 2021.

The GFP-SPO was officially launched on Feb 16, 2022, via a webinar. In attendance were representatives of CPOPC member-countries and observer countries – Indonesia, Malaysia, Colombia, Thailand, Ghana, Honduras, the Philippines, Sierra Leone and Papua New Guinea – as well as stakeholders in palm oil sustainability schemes.

At the launch, CPOPC Executive Director Tan Sri Dr Yusof Basiron asserted that palm oil contributes to the SDGs: “CPOPC believes that palm oil is a sustainable alternative to other vegetable oils such as soybean, rapeseed and sunflower across all the three SDG focus areas – social, economic and environmental.

“Therefore, the GFP will be used as a reference because its principles will draw and expand upon the current sustainable palm oil certification schemes, such the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) and Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil, and provide guidance to future ones.”

Indonesia’s Deputy Minister for Food and Agribusiness, Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs, Dr Musdhalifah Machmud, emphasised: “In collaboration and support of the current certification schemes, the GFP-SPO can provide a common language across systems and benchmarks. It is worth noting that this framework is voluntary and is not intended to be a new palm oil certification scheme but rather, a critical reference applicable to existing and future schemes.”

Malaysian Ministry of Plantation Industries and Commodities Secretary-General Datuk Ravi Muthayah said: “The GFP-SPO is important in ensuring that palm oil is able to meet world demand in a sustainable and productive way by adhering to the SDG principles. The principles are global in nature and universally applicable, taking into account different national realities and levels of development.”

Platform for producers

Presenting an overview of the global demand of palm oil and the framework, Sustainability Consultant Ziv Ragowsky reaffirmed that the GFP-SPO is a platform of collaboration among the producers of vegetable oils.

The idea of having the framework is to have discussions between palm oil producing countries, other stakeholders and the UN; and to have a positive discourse that avoids difficulties and frictions in pitting one stakeholder against another, he said.

Team Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil Secretariat Coordinator Dr Herdradjat Natawidjaja connected the GFP-SPO and ISPO in covering the 7 Principles towards achieving the global SDGs.

The principles are compliance with regulations; implementation of good agricultural practices; management of the environment, natural resources and biodiversity; responsibility to workers; social responsibility and community economic empowerment; application of transparency; and sustainable business improvement.

Malaysian Palm Oil Certification Council representative, System Management Department Senior Manager Simon Selvaraj, shared that the framework would be useful in coordinating Indonesian and Malaysian sustainability efforts from the economic, environmental and social aspects.

The framework has elevated the bar in sustainability requirements because it is able to holistically measure the UN SDGs, he noted, adding that the GFP-SPO would play a wider role in addressing sustainability issues with early adoption. This will significantly help everyone in the supply chain.

CPOPC Deputy Executive Director Dupito Simamora concluded the webinar by affirming the continued efforts of palm oil producing countries to attain a sustainable supply chain, “Palm oil has led by examples to continuously improve the sustainability framework, which should be emulated by producers of other vegetable oils. International support would be required from other palm oil producing countries, relevant organisations, as well as UN bodies for the framework to be extrapolated to all oils,” he said.

Co-creating solutions

The second introductory webinar on March 4, 2022, was well attended by participants from palm oil producing countries in the Asia Pacific, Latin America and Africa; UN agencies; the private sector; associations of smallholders; scientists; producers of other major vegetable oils; media; national and international NGOs; and major palm oil consuming countries.

The main focus was the visible progress recorded by the palm oil industry on sustainability. As it is not meant to be a certification scheme, the framework is to act as the primary reference for the palm oil sector, led by the CPOPC.

Another important aspect highlighted steps to make this framework a basis for better governance of the palm oil sector; a foundation for transformative dialogue on sustainability for all vegetable oils; and collaboration needed at regional and global levels.

UNDP Indonesia’s Senior Management Advisor/Head of Environment Unit Dr Agus Prabowo emphasised the contribution of sustainable palm oil in transforming the food system. He observed that the framework reflects the excellent work of CPOPC as an example of the transformation that the world needs to improve the state of the food system.

He recalled the message of the UN World Food Summit – ‘making our food system more sustainable’ – and said the framework is a powerful way to change course and make progress towards all 17 SDGs. He added that this distinctive approach and perspective in specifically addressing the SDGs is greatly appreciated.

Solidaridad Managing Director Dr Shatadru Chattopadhayay expressed strong support for the framework. He suggested two pathways for the common framework to go further, by taking the government to government and business to business approach respectively.

He underscored that it is important to have a level playing field for all oils and fats industries and oleochemicals in Asia, to prevent discrimination against palm oil. In this respect, the framework could provide a platform for dialogue with India, China, the European Union, Africa and South America.

The CPOPC Secretariat will continue to strive for the ultimate goal of the GFP-SPO – to start a collaboration with relevant stakeholders, including other producers of vegetable oils, to make sustainability the norm.

The way forward is to co-create solutions by strengthening sustainability standards for the palm oil sector and other vegetable oils in a spirit of partnership, while rejecting any unilateral decision on what is considered sustainable or not.

As the framework is centred in the UN SDGs, there is a clear need to introduce it to all relevant UN bodies and agencies, and to forge further dialogue with all parties to realise a global standard for all oils.

CPOPC

Jakarta, Indonesia

This edited version was compiled from reports posted at:

– https://www.cpopc.org/the-launching-of-global-framework-principles-of-sustainable-palm-oil/

– https://www.cpopc.org/category/pressroom/

By gofb-adm on Sunday, May 1st, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Comment No Comments

The European Union (EU) has long been at the forefront of regulatory advancement and innovative policies on trade and sustainable development, as well as the formulation of rules of commerce that directly affect third countries. The sheer breadth and depth of EU regulation are not comparable with most other regulatory environments, and often lead the way for other countries to follow suit.

To date, much of its attention has been directed at the palm oil industry – be it the increasing regulation of process contaminants like 3-MCPD; the detailed limits on nutrition and health claims, as well as food labelling; or policies to protect forests and prevent deforestation.

The conditions of market access for palm oil to the EU have further been influenced by unfounded campaigns in some member-states. These have created negative sentiments about the use of palm oil in food products and as a feedstock for biofuels, and exerted pressure for strict legislative controls.

New regulatory and legislative initiatives are now pending in the context of the European Green Deal, which sets out efforts for the EU to become the world’s first climate-neutral continent. The Farm to Fork Strategy aims for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system, while the Fit for 55 package targets policies in relation to climate, energy, land use, transport and taxation to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030. These are all set to apply to palm oil as well.

There are two key reasons why the Malaysian palm oil industry should take heed of these developments, and work within this environment to protect its trade interests.

Firstly, the EU has become an incredibly important ‘laboratory’ for new policies and novel regulatory approaches. It may be argued that it develops these complex measures unilaterally, but there is little doubt that its initiatives eventually do have an impact on the global trade environment.

Secondly, Malaysia’s palm oil industry – and the many people depending on it for their livelihood – continue to rely strongly on exports to the lucrative EU market. From 2010 to 2020, the EU ranged between second and third ranking as a destination for Malaysian Palm Oil. In 2020, it represented Malaysia’s second-most valuable export market for palm oil and palm-based products, with a value of around RM11.27 billion (EUR 2.35 billion).

Even the anticipated decline in EU demand for palm oil used for biofuel production and for oil palm crop-based biofuel will not see the commodity being immediately replaced. It will certainly not be offset by demand in other major markets, such as India and China, which offer relatively little additional room for expansion of their palm oil imports from Malaysia.

In addition, competition from other palm oil producing countries, as well as other vegetable oil producers, will reduce the possibility of new markets being found. Therefore, if only from a purely commercial perspective, the EU remains an important export destination for Malaysian Palm Oil.

Legislation on supply chains

In the coming months, the EU is expected to unveil a proposal for a new legal instrument that looks poised to affect supply chains around the world. Given that it will apply along entire supply chains, the proposed legislation will not only affect direct trade between the EU and a third country, but all countries along the supply and value chains.

In December 2021, the European Commission (EC) presented its proposal for an EU Directive on Sustainable Corporate Governance. This is expected to put forth detailed due diligence obligations related to social (labour) and environmental standards in corporate supply chains, as well as obligations for corporate directors to integrate mandatory sustainability criteria into their decision-making processes.

Similarly, in the context of the legislative initiative on deforestation and forest degradation – to reduce the impact of products placed on the EU market – the EC intends to ‘promote the consumption of products from deforestation-free supply chains in the EU’.

These initiatives will have implications for economic operators around the world – implications that many businesses may not yet fully realise, assess or appreciate until the rules are in place.

The impact may not be felt until, for instance, a food processing company in India requests its Malaysian Palm Oil supplier to comply with detailed social and environmental obligations, so that the Indian company’s products can be purchased by a European business that is required to comply with the new due diligence obligations.

Should Malaysia’s palm oil exporters decide to ship crude palm oil to India, for example, in order to avoid certain EU regulations, the strategy will be short-lived if the processed products containing Malaysian Palm Oil are then exported from India to the EU.

The rules on increased supply chain due diligence will mean that products exported to the EU from anywhere in the world and containing Malaysian Palm Oil would still be required to fulfil a certain number of criteria related to social and environmental standards.

In the context of the EU’s initiative on deforestation and forest degradation, additional due diligence rules that aim at ensuring that no deforestation has occurred, can also be expected. Given the ‘score’ accorded to palm oil in the EU’s previous elaborate calculation of the indirect land use change risk, it is likely that similar rules will also apply to palm oil for uses other than biofuel production.

Circumventing such rules by exporting to other markets will not be a sustainable option, as third markets would need to align themselves to EU standards and regulations in order to preserve their own trade opportunities.

Staying ahead of the curve

As the examples of the imminent due diligence obligations indicate, EU rules often affect other regulatory environments. This may, in turn, cause other countries to consider similar rules to harmonise requirements and thereby facilitate trade.

In simple terms, Malaysia and its palm oil industry should closely monitor and ‘police’ the EU market and regulatory initiatives, so as to always remain abreast of developments vis-à-vis global regulation. This is a prerequisite to preserving market access opportunities in the EU, and defending Malaysia’s rights within the international trading system should the need arise.

This would allow economic operators in Malaysia to understand in which direction the world is moving in terms of regulation – and therefore assess, influence and/or align with the standards-setting process in the EU and, ultimately, globally.

Without such coordinated and constant engagement, Malaysia will not only progressively lose the important EU market, but also be unable to understand, adapt or influence such initiatives in the EU or elsewhere. If anything, keeping up with developments in the EU would allow Malaysia to anticipate commercial and regulatory trends, and thereby remain competitive and attractive.

Merely directing its palm oil exports to other destinations may provisionally and partly compensate for losing the EU market, but will not fully relieve the Malaysian industry from complying with certain EU rules.

Therefore, Malaysia should not give up on the EU market, but rather increase its engagement in a way that allows European stakeholders to better understand Malaysia’s commitments to social and environmental standards. Such involvement will also allow Malaysia to contribute to the shaping of fairer EU rules.

Malaysia and its palm oil industry already have a long history of sophisticated engagement with EU regulators through the efforts of government agencies and industry stakeholders. Such efforts should continue and be even better coordinated and deployed.

Wan Aishah Wan Hamid

CEO, MPOC

By gofb-adm on Sunday, May 1st, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Markets No Comments

On Nov 17, 2021, the European Commission (EC) published its proposal to regulate commodities and products available in – or exported from – the European Union (EU) market, if these are associated with deforestation and forest degradation. As it stands, the scope will apply to palm oil and its products.

The EC first expressed this intention in its 2019 ‘Communication on Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests’. The European Green Deal, as well as the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the Farm to Fork Strategy, have since confirmed this commitment.

Additionally in the EU, there is an overall trend towards requiring business operators to establish and implement greater due diligence procedures. As such, the EC is also working on a directive on such measures that would apply to the broader supply chain, to ensure compliance with social and environmental standards.

Currently, when it comes to forests and timber, the EU legislative framework focuses on addressing illegal logging and associated trade, but does not address deforestation and forest degradation directly. The two main legal instruments in force are the Timber Regulation and the Regulation establishing a Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) licensing scheme for imports of timber into the EU.

Under FLEGT, the EU negotiates Voluntary Partnership Agreements with producer countries, to ensure that timber and timber products exported to the EU come from legal sources. Once a consignment is FLEGT-certified, this indicates the legality of the timber and relieves the exporter of further due diligence.

However, evaluation of the Timber Regulation and FLEGT has revealed that, while there has been a positive impact on forest governance, two main objectives have not been met – to curb illegal logging and related trade; and to reduce the consumption of illegally harvested timber in the EU. The evaluation concluded that only focusing on the legality of timber was not sufficient and that the Timber Regulation should be amended. The proposed Regulation will therefore repeal the Timber Regulation, while FLEGT will remain in place.

Six commodities selected

The EC argues that the proposed Regulation should cover those commodities whose consumption in the EU is the most relevant in terms of contributing to global deforestation and forest degradation.

As part of the study supporting the Impact Assessment for the proposed Regulation, an extensive review of scientific literature was carried out. This process delivered a first list of eight commodities, which was then reduced by comparing the estimated area of deforestation linked to EU consumption for each commodity with its average value of EU imports.

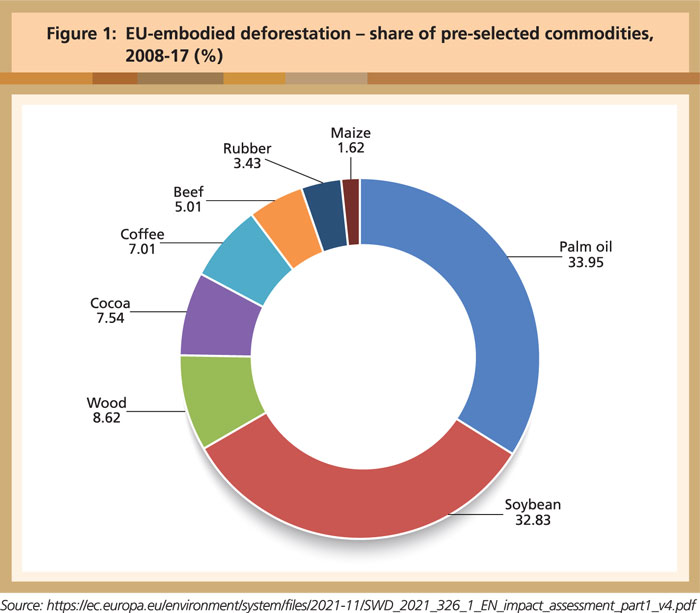

The EC concluded that six commodities represent the largest share of EU-driven deforestation among the eight analysed – palm oil, soybean, wood, cocoa, coffee and beef, as well as maize and rubber (Figure 1).

The EC said maize and rubber account for the smallest fractions of the commodities analysed, but that their trade volumes are very large. Therefore, it concluded that including the two commodities in the scope of the future Regulation would require a very large effort and significant financial and administrative burden, with limited return in terms of reducing deforestation driven by EU consumption.

With respect to palm oil and its products, Annex I of the proposed Regulation lists the following products and related tariff lines:

The EC will undertake a first review within two years of the rules coming into force. Further reviews are to be made at regular intervals, thereby allowing for progressive amendment of the rules or for the extension of the product scope.

As part of the review, the EC is required to present a report to the European Parliament and the Council of the EU (Council), to be accompanied, if appropriate, by a legislative proposal. The report is to ‘focus in particular on an evaluation of the need and the feasibility of extending the scope of this Regulation to other ecosystems, including land with high carbon stocks and land with a high biodiversity value such as grasslands, peatlands and wetlands and further commodities’.

Global NGOs, such as Greenpeace and the World Wide Fund for Nature, have strongly criticised the exclusion of non-forest ecosystems, such as savannahs and wetlands, in the proposal. While the review and extension of the product scope may contribute to making the rules less selective and discriminatory, the reliance on EU-developed concepts like ‘land with high carbon stocks’ and ‘land with a high biodiversity value’ is questionable, as they are not supported by science and related research – and hence, no global definitions and benchmarks exist.

Due diligence approach

The EC emphasises that the selected commodities and products should not be placed or made available in – or exported from – the EU unless they are deforestation-free, and have been produced in accordance with the relevant legislation of the producer country.

Operators will therefore be required to establish and implement due diligence procedures to confirm compliance. To ensure this, the EC proposes the attachment of a due diligence statement, to confirm that no risk – or only a negligible risk – has been found. The statement is to contain detailed information on the goods and the economic operator. This approach has been followed under the Timber Regulation.

More specifically, the due diligence procedure laid out in the proposed Regulation is to include three elements:

Where a risk is identified, operators are to mitigate it to achieve no risk or a negligible risk. Once this is done, the operator will be allowed to place the relevant commodity or product on the EU market or to export it from the EU.

Third-party certification or other third-party verified schemes may be used in the risk assessment procedure, but should not substitute the operator’s responsibility in terms of due diligence. For the relevant commodities entering or leaving the EU market, the proposed Regulation tasks competent authorities with the verification of compliance via periodic checks. The reference of a due diligence statement will have to be made in the Customs declaration.

Country benchmarking system

The proposed Regulation is to combine the due diligence requirement with a benchmarking system that takes into account the producer country’s engagement in tackling deforestation and forest degradation.

The objective is to ‘incentivise countries to ensure stronger forest protection and governance, to facilitate trade and to better calibrate enforcement efforts by helping competent authorities to focus resources where they are most needed, and to reduce companies’ compliance costs’.

The countries will be placed in a low, standard or high risk category. The obligations of operators and EU authorities will vary according to the level of risk – with simplified due diligence duties for low-risk countries and enhanced scrutiny for high-risk countries. When the Regulation first takes effect, all countries will be assigned a standard level of risk, which is then subject to change.

A list of the countries that present a low or high risk will be published. The categorisation of risk will be based on the rate of deforestation and forest degradation; the rate of expansion of agriculture land for the relevant commodities; and production trends of relevant commodities and products.

The EC will further take into consideration any agreements concluded between the EU and producer countries that address deforestation or forest degradation; agreements that facilitate compliance with the proposed Regulation; and whether laws are in place in producer countries to enforce measures against deforestation and forest degradation, in particular ‘whether sanctions of sufficient severity to deprive of the benefits accruing from deforestation or forest degradation are applied’.

The proposed Regulation will now follow the EU’s ordinary legislative procedure and will have to be agreed and adopted by the European Parliament and the Council. Both institutions will develop their respective positions before entering into ‘trilogue’ negotiations with the assistance of the EC. Substantial changes to the proposed Regulation can be expected during these discussions.

While it is a welcome change that the EU has not targeted a single commodity like palm oil or timber this time around, the proposed mechanism still leaves a wide margin for discrimination of selected commodities and the countries where they are produced.

Producers of the targeted commodities should carefully assess the proposed Regulation and ensure that their positions are duly taken into account. A feedback period on the proposed Regulation will be opened soon by the EC and interested stakeholders should use this platform before the ‘trilogue’ negotiations are launched.

Uthaya Kumar

MPOC Brussels

By gofb-adm on Sunday, May 1st, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Cover Story No Comments

Like many other commodities, palm oil experienced high prices throughout 2021. Prices more than doubled over the past 18 months to a record high of US$1,213.85 a tonne in October 2021. In November and December, however, prices dipped and weighed on 2021’s average pricing to US$1,000 per tonne.

The high prices can be arguably attributed to lower palm oil output. For most of 2020 and throughout 2021, Covid-19 pandemic-led border closures had starved Malaysia’s oil palm estates of many foreign workers who had returned home and could not re-enter the country.

The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) also sees structural changes in the global palm oil supply due to a slowdown in new plantings throughout Indonesia and Malaysia since 2015. With the ageing tree profile across both countries, the replanting programme will also temporarily limit palm oil supply in the short to medium term.

As agricultural land becomes limited, oil palm replanting is key to boosting palm oil yield across Indonesia and Malaysia. It is important to replant to sustain supply because these countries produce about 85% of the world’s palm oil needs. LMC International highlights that the global palm oil supply will only see minimal growth in the 2019-22 period due to year-end floods and the labour shortage in Malaysia.

On the other side of the globe, severe drought at Canada’s farmlands in 2021 resulted in its smallest rapeseed harvest in 13 years. The lower-than-expected supply of soft oils induced the sharp rise in other vegetable oil prices to a 10-year high, which then had a spillover effect onto palm oil pricing. The limited supply of vegetable oils all over the world is likely to continue into the first half of this year.

Production outlook

Palm oil production in Indonesia was 6.7% higher in the second quarter of 2021, gathering pace from the 1.5% growth in the first quarter and spurred by better rainfall in 2020. Output in the third quarter of 2021, however, was slightly curbed by floods in Kalimantan, which disrupted oil palm fruit harvesting. In the fourth quarter, the Indonesian Palm Oil Association (GAPKI) announced that production had fallen further. Its initial forecast of a better harvest in the second half of 2021 than the first, did not materialise. So, for the full year, GAPKI has revised its palm oil output forecast to 46.6 million tonnes, down 0.9% from 2020.

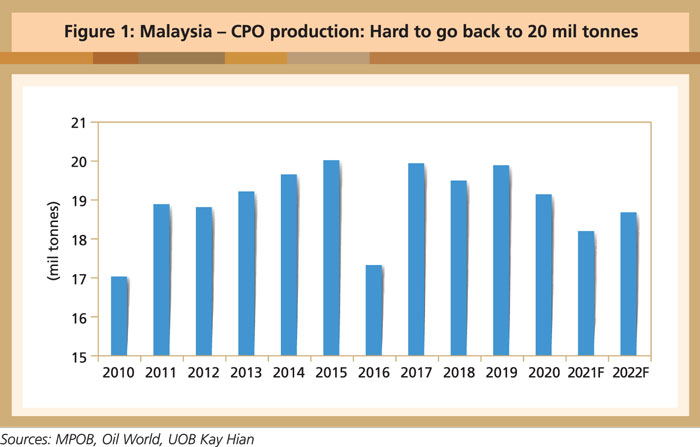

The Malaysian Palm Oil Board estimates that Malaysia’s 2021 palm oil output will drop to 18.3 million tonnes from 19.2 million tonnes in 2020. Palm oil ending stocks are expected to stay at below-average levels of 4 million tonnes in Indonesia and 2.1 million tonnes in Malaysia.

This year, Indonesian palm oil output is expected to recover due to good estate management and no halt of operations, supported by the absence of a La Nina impact. This, however, is not the case for Malaysia. Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, foreign workers who account for about 75% of the 500,000 harvesters employed on Malaysian oil palm estates have not been able to return due to border restrictions. Analysts forecast that Malaysia’s plan to bring in 32,000 foreign workers will only likely materialise towards March. The signing in December 2021 of a five-year memorandum of understanding between the governments of Malaysia and Bangladesh to hire more workers is a step in the right direction.

The second challenge is the high cost of fertiliser. Small farmers are expected to reduce fertiliser applications due to sharply increased prices, potentially reducing future output. Fertiliser and pesticide prices have surged significantly due to supply chain disruptions, higher demand, rising freight charges and input costs. The price of fertilisers, such as nitrogen and phosphate, has risen by 50-80% since mid-2021, while the price of herbicides, such as glyphosate and glufosinate, has more than doubled due to supply chain disruptions and more expensive raw materials.

It is also becoming difficult to obtain supplies. Thus, the oil palm sector may again suffer from low fertiliser applications this year. The cost of fertiliser is a major component after labour for oil palm growers, making up about 30-35% of the ex-mill costs. Companies will continue to feed oil palm trees this nutrient despite the high price, but may not receive the volume ordered due to supply constraints and uncertain shipment arrangements. Planters are highly dependent on imported fertilisers, but those in Indonesia have an advantage as local urea production is sufficient to meet domestic demand.

Based on industry sources, the estimated fertiliser imports for 2021 are 60-65% of the usual annual requirements. As the logistics bottleneck is unlikely to ease any time soon, 2022 could see even lower fertiliser imports. Smallholders may again be tempted to give less fertiliser to trees. The impact of reduced fertiliser usage in 2018 and 2019 still shows today, as yield recovery is weaker than normal. As a result, Indonesia and Malaysia may not be able to deliver much output growth in 2022.

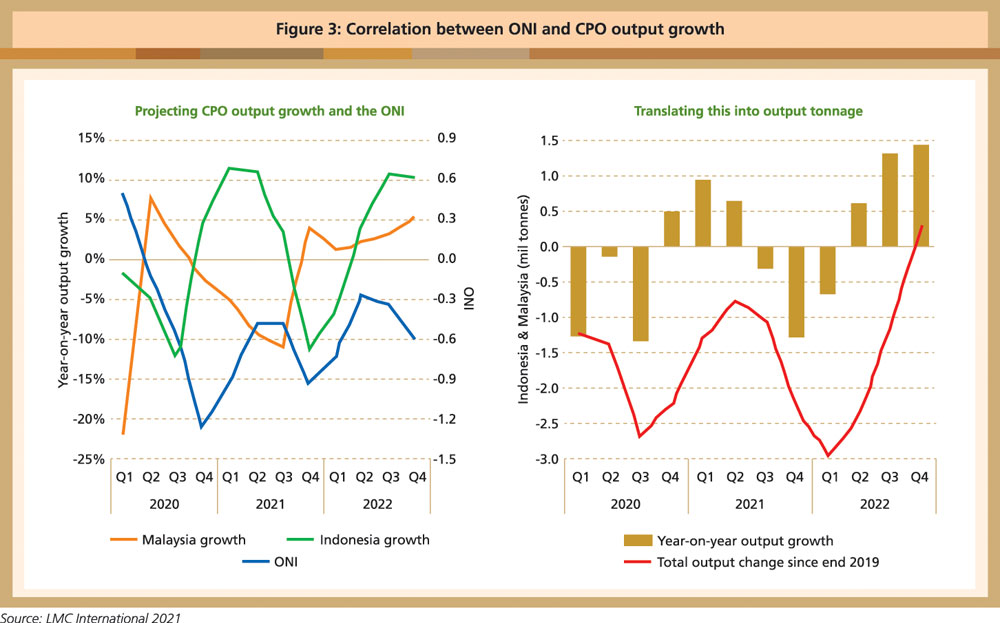

LMC International reports that Indonesia and Malaysia are in a long La Nina period in which the Oceanic Nino Index (ONI) is more negative than -0.5. The pattern of the ONI curve since 2020 echoes that of 2010-11, with La Nina weakening and then returning. If 2012 is taken as a guide, La Nina should end in 2022. A rising ONI is correlated with rising output growth, and a falling ONI is linked to slowing output growth. This is especially true for Indonesian production.

El Nino is a phenomenon of dry conditions for harvesting with the benefit of the previous year’s rains. With La Nina, there will be twin blows from heavy rainfall at estates and El Nino drought in the following years. In view of the apparent link between the ONI and output growth, in Indonesia, LMC International predicts that there will not be much palm oil production growth in 2022. The US National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration predicts a 95% chance of a weak La Nina lasting through February 2022.

Demand outlook

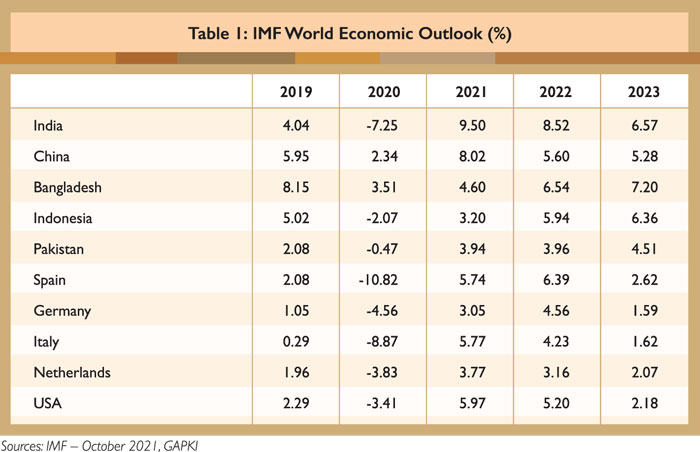

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its World Economic Outlook estimates that the global economy grew 5.9% in 2021 and will expand by 4.9% in 2022. The economic outlook will continue to be positive (Table 1).

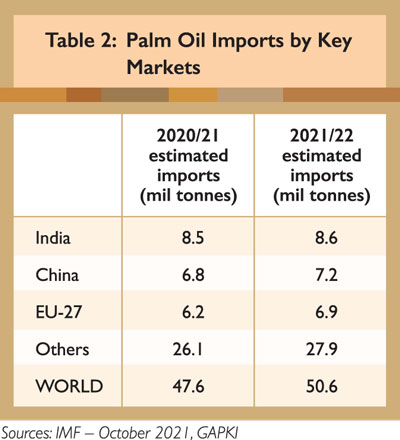

According to Refinitiv Agricultural Research, global palm oil demand for 2021/22 is forecast at 50.6 million tonnes, up 6.5 % compared to the prior season (Table 2), provided there is no large-scale demand destruction.

India’s palm oil purchases this year are estimated at 8.6 million tonnes in 2021/22. The slight increase is boosted by the reopening of business activities, multiple import tax cuts and lifting of import restrictions on RBD palm olein. However, the upside to higher palm oil imports is limited by its narrowing discount to soybean oil and sunflower oil.

Also, the Indian government implemented stock limits on edible oils in October 2021, regulating the stocks that retailers and wholesalers can carry. Despite higher domestic oilseed supplies (including soybean, rapeseed and groundnut) on the back of ample rainfall and planted area expansion, crushing activities have not kept up. So, lower domestic vegetable oil production may potentially prompt higher palm oil imports.

China is the world’s second-largest buyer of palm oil after India and imports about 6-7 million tonnes from Indonesia and Malaysia every year. This year, China’s palm oil consumption is expected to increase due to a lower supply of rapeseed oil and soybean oil. It is also seen to buy more palm oil products for animal feed.

China’s palm oil imports are expected to rise to 7.2 million tonnes in 2021/22 boosted by economic recovery. There were more shipments to China ahead of the Lunar New Year and Winter Olympics in February. However, the upside could be limited in the months ahead by recent higher soybean crushing activities amid better crushing margins, which will lead to higher domestic soybean oil supplies. Also, RBD palm olein’s discounts on soybean oil have been narrowing, thus potentially dulling consumer buying interests.

Exports to the EU are expected to be muted, partly due to unattractive palm oil prices for biodiesel blending and early implementation of the revised Renewable Energy Directive by some member-states. The European Commission’s proposed law and due diligence to require proof that agricultural imports are not linked to deforestation, could potentially dampen palm oil sentiment.

The EU-27 palm oil imports are estimated at 6.9 million tonnes in 2021/22. Although the reopening of economies and the competitive prices of palm oil versus other edible oils will likely increase overall demand in 2021/22, renewed lockdowns – following the discovery of the Omicron variant of the Covid-19 virus – have raised doubts. The impact on palm oil demand is unclear at this point.

Price outlook

Industry experts forecast a tight stock situation and higher prices to run into the first half of 2022. Key factors to watch are the pace at which foreign workers are allowed to return to Malaysia; the impact of massive floods at many oil palm estates in five states across Malaysia; high costs of fertiliser; and the impact of the Omicron variant on production recovery.

At the Indonesian Palm Oil Conference in December 2021, many market analysts forecast that palm oil prices would remain firm, supported by a limited vegetable oil supply in the first half of 2022. However, they differed as to when and how much the prices would fluctuate throughout the year.

LMC International indicates that tight supplies of palm oil, rapeseed oil and soybean oil have fueled the current high palm oil price. It cautioned that palm oil prices may be moderated by rising interest rates and hesitancy by major biodiesel users. It also predicted that there would be a small drop in the Crude Palm Oil-Brent premium until all vegetable oil output recovers in the second half of 2022. The key potential bullish factors that will keep prices higher are weather conditions until the first quarter of this year; a prolonged labour shortage at oil palm estates in Malaysia; oilseeds farmers refraining from selling; and biofuel policies.

GAPKI expects palm oil to stay above US$1,000 per tonne in the first half of 2022 and potentially for the rest of the year. It projects weaker output growth from Indonesian estates due to lack of new replanting, adverse weather and low fertiliser use. Indonesia’s palm oil stock for 2021/22 is forecast at 3.8 million tonnes, much lower than 4.9 million tonnes in 2020.

Palm oil trading trend in 2022 will depend heavily on the biodiesel mandate, which has been fueling price support. The success of the Indonesian Export Tax system provides significant insulation from further palm oil price volatility. This has also been aided by the level of vegetable oil stocks and the market’s tightness since the Covid-19 pandemic.

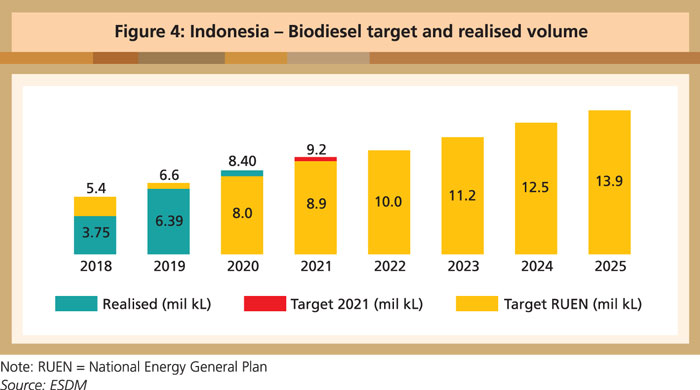

Indonesia’s B30 biodiesel mandate is likely to stay for 2022 and 2023 before the green diesel or hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) is commercially available. The government has raised the B30 biodiesel quota for 2022 to 10 million kilolitres. In 2021, Indonesia expanded its biodiesel allocation by 213,033 kilolitres to 9.4 million kilolitres. This will continue to support palm oil prices with the higher domestic demand.

Based on data from the Indonesian Palm Oil Fund Management (BPDPKS), the 2021 export levy collection is estimated at between US$4.87 billion and US$4.94 billion, of which US$3.4 billion or 70% is being used to support the B30 biodiesel programme. In 2022, BPDPKS estimates that the biodiesel mandate funding will be US$2.7 billion. Funding from the palm oil exports levy is still sufficient to support the mandate into 2022.

In 2022, Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources plans road tests on the B40 blend, in two options. The first is a 30% biodiesel and 10% HVO blend, and the second is a 30% biodiesel and 10% distillate fatty acid methyl esters combination. The government is executing a comprehensive study on the B40 blends and aims to partially implement this mandate in 2025. The biodiesel mandate and palm oil export levy collection are supportive of biodiesel production from 10 million kilolitres in 2022 to 13.9 million kilolitres in 2025.

Current developments look promising in the US. The USDA’s Economic Research Service recently projected higher soybean oil demand in 2022, while Rabobank foresees greater crush capacity beginning in 2023 as more renewable diesel facilities come online. Renewable diesel in the US has multiple government policies driving new production. The Renewable Fuel Standard generates renewable identification numbers for renewable diesel subsidy. There is also the US$1-per-gallon Biodiesel and Renewable Diesel Tax Credit that is set through 2022 but could be extended through 2026 in the Build Back Better Act.

Rabobank projects renewable diesel production to hit more than 6.1 billion gallons by 2030. That would push vegetable oil demand to about 21.4 million tonnes. To put that into perspective, Rabobank notes that the US is producing about 11-11.3 million tonnes. Basically, that requires double the volume of soybean and other vegetable oils to meet the demands of renewable diesel. Many analysts forecast continued high demand for soybean, inevitably boosting palm oil prices.

CPOPC is of the view that palm oil output will remain constrained with limited upside potentials, and that prices will likely continue to trade in the bullish range of US$1,000 per tonne. However, the palm oil price rally forecast in 2022 could be dampened by higher soybean oil output in Brazil.

In 2021/22, Brazil and Argentina’s soybean production is estimated at 147.9 and 45.8 million tonnes respectively. Record high soybean production is expected in the 2021/22 season unless adverse weather conditions amid La Nina significantly deteriorate growing conditions. The upside potential of soybean yields could also be limited by concerns over lower or delayed input applications, following soaring fertiliser and pesticide prices.

While these factors support bullish vegetable oils prices in 2022, there are worries over the recurrence of Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns due to the emergence of the Omicron variant, thereby slowing global economic recovery.

CPOPC

Jakarta, Indonesia

This is an edited version of the article which is available at

https://www.cpopc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CPOPC-OUTLOOK-2022.pdf