Malaysia’s Private Sector Palm Oil Association Launch Responsible Employment Charter

By gofb-adm on Thursday, December 23rd, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, News No Comments

By gofb-adm on Thursday, December 23rd, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, News No Comments

The Malaysian Palm Oil Association (MPOA) has announced a new Responsible Employment Charter that commits all members of MPOA to a binding set of commitments on labour rights.

The Charter can be read in full here and includes:

The Chairman of MPOA, Dato’ Lee Yeow Chor, made the following statement:

“The Malaysian oil palm industry, which has a heritage dating from the European management days, has a long history of respecting labour rights and adopting good labour practices. This Charter represents the commitment of the industry to follow international best practice on labour policies and practices”.

MPOA’s membership of palm oil growers takes very seriously the forced labour allegations made in the United States and in Europe – and are taking concrete steps to address those allegations, and make the necessary reforms.

Read the full statement by MPOA below.

****

Malaysian Palm Oil Association Launches Responsible Employment Charter

Malaysian Palm Oil Association (MPOA) today announced the launch of its Responsible Employment Charter.

The Charter affirms the commitment of its members to respect labour rights, adopt responsible recruitment practices and provide good working and living conditions for their workers.

The commitments in the Charter are based on several international guidelines and frameworks, namely –

MPOA members also commit to comply with all Malaysian labour laws and Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) Principles & Criteria relating to labour rights and practices.

Dato’ Lee Yeow Chor, Chairman of MPOA said:

“The Malaysian oil palm industry, which has a heritage dating from the European management days, has a long history of respecting labour rights and adopting good labour practices. This Charter represents the commitment of the industry to follow international best practice on labour policies and practices”.

MPOA believes this Charter will complement the effort of the Malaysian government in introducing the National Action Plan on Forced Labour 2021-2025 and committing to ratify the ILO Protocol to Forced Labour Convention.

About the Malaysian Palm Oil Association

MPOA is the national association recognized by the Malaysian government as representing the interests of oil palm growers in the country. Its members represent a broad spectrum ranging from the big (more than 300,000 planted hectares) to small (less than 120 planted hectares) companies involved in the cultivation of oil palm and other plantation crops such as rubber and coconut. Established in 1999, MPOA has more than 120 members representing about 1.8 million hectares of planted land in Malaysia.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Environment No Comments

In March 2021, the World Resources Institute (WRI), a global research non-profit organisation operating since 1982, issued its annual ‘Global Forest Review’. They found that 12.2 million ha of tree cover was lost in 2020 – a 12% increase from 2019.

Sadly, nearly one-third of that loss occurred within tropical primary forests which are crucial to storing carbon and maintaining biodiversity – these are among the world’s best chances of mitigating climate change.

For the second year in a row, Brazil topped the list of nations that experienced staggering primary forest loss. The country lost nearly 1.7 million ha to fires and clear-cutting. Not only was this loss a 25% increase from 2019, but it was also three times higher than the second country on the list: the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Although most of the primary forest loss in Brazil occurred in the Amazon, the Pantanal – the world’s largest tropical wetlands – experienced 16 times more primary forest loss, as land was cleared for development projects, agriculture and cattle pastures.

The WRI data, provided by scientists at the Global Land Analysis and Discovery laboratory at the University of Maryland in the US, clearly denotes that key targets were missed in 2020 and that deforestation rates are climbing to new highs. Now, more than ever, we must reimagine our policies and economies in a way that protects forests.

Against this backdrop, though, the declining national deforestation rate in Southeast Asian nations like Malaysia and Indonesia provided a rare glimpse of hope for the world’s forests.

While Brazil’s deforestation increased dramatically, Malaysia’s forest loss was reduced – its rate fell from sixth-highest on the list to ninth in just one year. This was the steepest drop registered by any nation on the list, and followed a trend that Malaysia has been setting for four years.

According to the report, government actions are in part to be credited for this downward trend. In 2019, Malaysia began a five-year cap on plantations, as well as increased the fines and jail terms for illegal logging, in accordance with stringent adherence to forestry laws.

Corporate commitments from the pulp, paper and palm oil sectors also played a substantial part in the rollback of forest loss. Currently, 83% of palm oil refining capacity in Malaysia and Indonesia come under the No Deforestation, No Peat and No Exploitation commitments, all of which have helped the producer nations decrease deforestation.

The progress in Malaysia has also specifically coincided with the implementation of the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification scheme. Under this programme, a moratorium on oil palm expansion has been enforced to protect 50% of forest cover, while ensuring that all palm oil is 100% sustainable.

In this context, disinformation that discredits palm oil, or policy-decisions like that of the EU – to phase palm oil out of the bloc’s biofuels market by 2030 – must be rejected, especially as they appear to overlook the progress and efforts that developing nations like Malaysia have put into keeping forests healthy and commodity-production sustainable.

Blanket restrictions unacceptable

Only a few days before the WRI report was launched, researchers from the Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden and the University of Louvain in Belgium conducted a robust analysis of more than a thousand proposals on curbing imported deforestation.

These proposals originated from open consultations and workshops, where the EU gathered ideas from companies, interest groups and think tanks, to put together the most potent and politically feasible policy framework that can effectively address issues of imported deforestation.

The findings of the study, titled ‘Eighty-Six EU Policy Options for Reducing Imported Deforestation’, cautioned against imposing blanket restrictions on commodities. Instead, the researchers recommended that importers be held accountable and responsible by requiring them to carry out and prove due diligence throughout the product’s supply chain.

The study also encouraged conducting multi-stakeholder forums, which includes companies, politicians and civil society groups, for decision making pertinent to the removal of a supply chain, commodity or area of deforestation. Including more affected parties would lead to wider acceptance of policies.

The researchers also proposed measures to balance the trade-off between the proposed policy’s effect and its feasibility. For instance, they recommended pairing trade regulations – that tend to hit poorest countries the hardest – with provision of aid, so that nations can pursue sustainable production.

This could also help reduce the risk of unsustainably produced goods being exported to regions other than the EU. For instance, China, which is the world’s second-largest palm oil importer, recently gave investors access to the palm oil trade with no stipulations for sustainability. This is dangerous and will result in creating what is known as a ‘leakage market’, which could end up derailing efforts like the MSPO.

The reality of our food cycle is that the world is highly dependent on palm oil. It contributes, for example, to the diet of half of humanity and provides a livelihood for millions of smallholder farmers.

The oil palm is the most efficient of vegetable oil crops – yielding the most oil while using the least amount of land. This is why it is important to work with palm oil producers to balance growing demand with innovation that safeguards the natural world.

But we must acknowledge existing flaws. While Southeast Asian states have raised hopes in the fight against deforestation, the global trend paints a grim picture. Total carbon emissions resulting from forest loss in 2020 alone equaled 2.64 Gt – equivalent to the annual emission of 570 million cars, more than double the number of vehicles currently on US roads.

These realities are a stark reminder that efforts by Malaysia and Indonesia, while commendable, will only succeed when the comity of nations comes together. National policies will continue to have the most impact on forests – but, without global cooperation, the impact may remain limited in the face of climate change.

The Centre for Palm Oil Studies

This is an edited version of the article available at: https://thecspo.org/southeast-asian-countries-provide-hope-for-global-forests-world-resources-institute/

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Sustainability No Comments

Musim Mas has partnered with Nestlé and AAK to address deforestation in Aceh, Indonesia. Such multi-stakeholder collaborations are essential for achieving the transformational change necessary to foster a deforestation-free supply chain.

Creating meaningful change will require Musim Mas to navigate some of the challenges that come with a vast supply base. But doing so will unveil best practices that can be shared with peers – furthering industry-wide efforts to make sustainable palm oil the norm.

Efforts are being made to engage independent smallholders in this process. They join private sector actors, NGOs, suppliers, financial institutions and the local government in playing a key role in supporting a forest-positive future.

About 40% of Indonesia’s palm oil is produced by smallholders. As the biggest and fastest growing group of producers, they are expected to occupy more than 60% of the cultivated area by 2030. Therefore, achieving ambitious deforestation and sustainability goals would be impossible without engaging them.

To further its own traceability efforts, Musim Mas has prioritised collaboration with smallholders, who provide 40% of its production volume. It is estimated that up to one million farmers currently participate in the company’s supply chain.

The Musim Mas Sustainability Policy – which lies at the heart of its endeavours – was updated in September 2020 to reflect a strict stance on the 2025 targets of NDPE – No Deforestation, No Peat and No Exploitation. The policy also lays out a renewed social commitment to improve the livelihood of smallholders and their communities.

Above all, palm oil production is a people business. Implementing the Supplier NDPE Roadmap has already facilitated engagement with more than 32,000 independent smallholders, with more to take place in the coming years. Prioritising multi-stakeholder collaboration in the Aceh-Leuser Ecosystem, Siak and Pelalawan regions, Musim Mas is supporting smallholders and their livelihood, while targeting a more sustainable palm oil future.

However, there are several obstacles to overcome. Most smallholders have inaccurate land titles or lack them altogether. Because they are not bound by contracts or they do not have a permanent relationship with continuous sales to mills, data collection on this group has proven to be a challenge.

Smallholders are farmers with less than 25 ha of planted oil palm. In Indonesia, they only manage 2 ha per household on average, often relying on family to fulfil labour demands. While scheme smallholders are bound by contracts and don’t have the autonomy to work with a mill operator or agent of their choice, they do have a high level of access to assistance from government agencies, businesses or cooperative societies.

This level of access to assistance schemes is uncommon for independent smallholders. They are also associated with smaller yields and less regulatory adherence to certification schemes like those of the RSPO and ISPO. Without government or organisational assistance, they face a lack of access to technical advice and market data. All these factors compromise productivity and sustainability efforts.

Perhaps most importantly, independent smallholders face difficulty in securing loans or capital. With such resources not readily available, smallholders are less likely to achieve – or even want to achieve – sustainability certification. Musim Mas has recognised that it is best to focus efforts on livelihood and people, so that sustainability improvements may follow.

Solutions to problems

With productivity rates as much as 45% below company production levels and their distance from supply chain sustainability efforts, smallholders require much support when it comes to sustainable palm oil production.

When they face concurrent issues like poverty, gender inequality, limited education and a lack of resources, sustainability isn’t often a top priority for smallholders. As such, Musim Mas’ solutions are oriented around independent smallholder success, with the understanding that this forms a basis for improvements to come.

Partnership with IFC

This understanding was the catalyst for Musim Mas’ partnership with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group. Following a 2013 diagnostic study on smallholders, a pilot programme was launched in 2015.

The project initially engaged smallholders who supply the company’s mills, assisting them to overcome issues faced in their journey towards sustainable palm oil production. Centred on the pillars of environmental, business management and social support, the programme has provided smallholders with invaluable knowledge and has taught them new ways to secure financial assistance.

The success of the pilot programme led to a modified version being implemented in several mills and supplier mills in Riau, one of the top supplier provinces with 23% of total crude palm oil procurement. The company has since extended the programme to include independent smallholders in the neighbouring areas of Aceh and South Sumatra.

Priority landscapes

Musim Mas has further identified four priority landscapes, where projects have been implemented to support the intersections between biodiversity, food security, livelihood and forest well-being.

In Aceh, Riau, South Sumatra and West Kalimantan, support is being provided to smallholders who do not have the resources and capacity to make sustainability improvements. This includes those who have limited access to knowledge, are uncertain of land legality, and are unable to access government support.

In South Sumatra, an Extension Services Programme has engaged 395 smallholders for training on Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) since December 2017. Separately, in partnership with Rainforest Alliance, a project was completed in 2019 to address sustainability issues common to independent smallholders. This in turn paved the way for a jurisdictional approach and future sustainability efforts for the regency in North Sumatra. This programme, also conducted with Rainforest Alliance, has trained 525 smallholders.

While it only makes up 5% of Musim Mas’ supply base, West Kalimantan was selected for the establishment of a Smallholder Programme in November 2019. In addition, the company facilitated a partnership with Earthqualizer on an agroforestry training project in 2021. Helping to balance forest conservation with economic development, the project has educated suppliers, smallholders and local communities on land legalisation, forest management practices and sustainable land-use business models.

Smallholder Hubs

With the awareness that smallholders are indispensable when it comes to achieving sustainable production goals, Musim Mas has built upon the partnership with IFC to establish Smallholder Hubs since 2020. To date, these have been set up in Aceh Tamiang, Aceh Singkil and Dayun, Siak. The Smallholder Hub is a platform where palm oil companies can share their expertise and resources to train independent smallholders, regardless of who they sell to, within a specific district.

Designed to address some of the constraints faced by smallholders, these hubs work to advance GAPs, facilitate sustainable plantation management, and enable access to financial and market opportunities. To date, this programme – Indonesia’s largest and most ambitious initiative – has reached more than 35,000 independent smallholders.

Due to its unique history, biodiversity and the fact that Aceh contains 87% of the Aceh-Leuser Ecosystem, the province has been prioritised for Smallholder Hubs. Ongoing deforestation has signified a high-risk landscape, further demonstrating the need for intervention. With risk comes potential for opportunity, which is why one Smallholder Hub was launched in Aceh Tamiang and another in Aceh Singkil, in collaboration with General Mills.

The Smallholder Hub in Aceh Tamiang has trained more than 73 village agriculture officers and 95 smallholders. Consistent with that of other Hubs, the curriculum covers GAPs (such as fertiliser management and integrated pest management); financial literacy; and NDPE. As part of the Inisiatif Dagang Hijau (Sustainable Trade Initiative) in Indonesia, the multi-stakeholder partnership has played a key role in the implementation of the Green Growth Plan across commodities in Aceh.

Similarly, in Aceh Singkil, the Smallholder Hub has produced 75 trained village officers and 310 smallholders. With the local government and General Mills as partners, the Hub has provided insight into the importance of land legality, and demonstrated how permits, land title certificates and Surat Tanda Daftar Budidaya (Cultivation Registration Letters) are essential for sustainable management of oil palm farms.

In spite of complications brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic, the Hub and support from the Earthworm Foundation have still been able to engage smallholders, hold multi-stakeholder workshops, and promote best practices to address deforestation as well as labour and social issues.

The third and most recent Smallholder Hub was a result of Musim Mas’ partnership with AAK and Nestlé. Funding during the first two years of the five-year project from these companies will enable about 1,000 independent oil palm smallholders to enrol in the programme and access training on sustainable agricultural practices. While helping smallholders increase their yield and earnings in existing areas of production, the programme will also reduce encroachment into protected areas.

Nestlé has committed to a deforestation-free palm oil supply chain by 2022; therefore, this partnership is essential in keeping planting within concession areas, minimising deforestation and protecting Aceh’s rainforests. Furthermore, it supplements governmental efforts to curb deforestation rates in the Leuser Ecosystem – the rate has already dropped sharply by this year, by more than 81% of the 2018/19 level.

Social and sustainability benefits

Indonesia is home to more than 2 million smallholders. The formation of cooperative societies has enabled them to benefit from support from other farmers, as well as to enhanced access to superior seeds and governmental replanting subsidies. This has pushed the best interests of the smallholders forward, while contributing to Musim Mas’ sustainability goals.

In the Aceh region alone, 100% of suppliers have an NDPE policy or have adopted the Musim Mas Sustainability Policy. Several of the UN Sustainable Development Goals are also supported in these efforts:

On the ground, these benefits are evidenced by stories like those of Heddie Munthe, a smallholder who accessed microfinancing to support her fertiliser purchases; or Lagut, a smallholder worried about seed purchases, who obtained governmental replanting subsidies.

Whether it is finding support to broker a deal with Unilever, implementing GAPs to increase yields and income, or encouraging female farmers to take on decision-making roles in a male-dominated industry, there is no shortage of successful case studies in the Musim Mas programmes.

If Musim Mas is to achieve NDPE compliance and a more sustainable palm oil supply base by 2025, it is crucial that no stakeholder group gets left behind. Efforts to engage smallholders are essential, as these bring together multiple players within a landscape – buyers, suppliers, brands, NGOs and civil society organisations. More importantly, synching industry efforts with local government initiatives ensures the best outcomes.

Ultimately, by supporting a diverse group of smallholders and their needs, Musim Mas will be one step closer to a fully traceable supply chain, while helping the industry to make sustainable palm oil production the norm.

Musim Mas

Headquartered in Singapore, Musim Mas is a privately owned, vertically integrated company involved in each point of the palm oil value chain.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Markets No Comments

The Covid-19 outbreak has had a devastating impact on the global economy over the past two years. Governments have been feverishly attempting to adapt to the rapidly changing dynamics and mitigating the impact of the pandemic. The lockdowns and movement restrictions caused 114 million people to lose their jobs in 2020, while food prices continued to rise.

The unpredictability and volatility brought on by Covid-19 have intensified discussions related to nutrition and food security. People in low- and middle-income countries generally feel the impact more severely (Table 1), because they spend a larger share of their earnings on food than those in high-income countries. Fortunately for the food sector, palm oil has been produced without interruption to meet global nutrition and food security needs in terms of edible oil.

As the pandemic began to be realised in February/March 2020 and lockdowns were imposed – first, in China and later in other countries – palm oil prices began to fall. It was speculated that, with the lockdowns, demand for palm oil by the hotels, restaurants and café (HORECA) sector would be reduced and prices would be further weakened. Producer countries projected reduced imports by buyers.

However, the palm oil industry in Indonesia and Malaysia was allowed to continue operating during the lockdowns. As a result, production continued to increase in 2020 and 2021 in Indonesia. Malaysian production was affected by labour shortage, as workers could not be hired back by the plantation companies due to travel restrictions. But overall, palm oil was sufficiently and sustainably produced to provide added food security for the world (Table 2).

The initial fall in the price of palm oil was attributed to China’s inability to import the commodity, as the lockdowns disrupted logistics in the supply chain. China had to use its existing stocks while waiting to import palm oil again. The price recovered after June 2020, as China began importing its monthly requirement (Figure 1).

Since then, palm oil prices have remained relatively high compared to historical levels, reflecting strong demand. This has some interesting implications as it may indicate new challenges and opportunities for the oil palm industry going forward.

On hindsight, continued palm oil production was a good thing for the consuming countries in terms of enhancing their food security. For the producer countries, the much-needed revenue supported weakened economies. Demand for palm oil remained robust, as low consumption in the HORECA sector was offset by increased use in home cooking and takeaway food services, arising from ‘stay at home’ and ‘work from home’ policies to curb the spread of Covid-19.

Market-related aspects

The long-term, post-pandemic outlook for the palm oil industry remains bright. Since the last quarter of 2019, palm oil supply and demand are back in balance, while stocks are declining. Prices have been relatively high for most of 2020 and 2021.

The increased revenue has been very welcome to producer countries. Oil palm farmers have received good prices for fresh fruit bunches. Also, they have not been as badly affected as workers in other sectors who have been subjected to lockdowns, pay cuts and job losses.

Consumers, however, have been affected by the high prices of oil and fats. The lower supply of rapeseed and sunflower oil, as well as strong demand for soybean and its oil, have led to the recent high price of soybean oil. But the lower price of palm oil relative to soybean oil has benefitted consumers, especially those whose incomes have been affected by the economic slowdown due to the pandemic.

The current trend of a long period of high prices experienced by palm oil – and other oils and fats – may be part of a new long-term shift in the supply and demand balance of these commodities.

While demand for oils and fats has grown due to the expanding global population, palm oil supply may not be growing at as high a rate as in the past. The moratorium on new land expansion for oil palm cultivation in Indonesia and similar lack of new land in Malaysia have limited the growth rate of palm oil production in recent years and in the long term.

As other oils and fats have been growing at a lower rate than palm oil, it is unlikely that the next major crop – such as soybean – will grow at a super-high rate to compensate for the lack of rapid expansion in palm oil production. Therefore, the future supply of oils and fats has to experience a slowing growth relative to demand. Prices have to rise to reflect this new supply and demand balance. If this outlook holds true, palm oil producers will see good returns.

Maximising the production of palm oil will have to be pursued by improving yield through better agronomic practices. If the industry can seize the opportunity to improve the yield by 50% – as with other oilseed crops – more than 35 million tonnes of palm oil can be additionally produced per year, without any land area expansion. This represents an opportunity for a huge increase in revenue for producers, given the projected high prices in the near future.

Proven benefits of palm oil

Palm oil plays a crucial role in providing the world with food oil as a source of consumers’ oils and fats requirement. Better affordability and availability compared to other oils imply that palm oil offers consumers the opportunity for assured food security. The main challenge is to enhance awareness of the nutritional properties of palm oil for better acceptance.

Numerous studies have suggested that palm oil provides beneficial health effects as a dietary oil. The proven evidence is embodied in a clinical study in the US on the cholesterol ratio effect of palm oil when blended with soybean oil or rapeseed oil as part of the diet. Consuming palm oil in such blended form helps improve the good HDL to the bad LDL ratio. The blended palm oil products have been commercially marketed in the US with success, and carry a FDA-approved label which says ‘patented blend to help improve cholesterol ratio’.

It is also known that, depending on the type of refining, palm oil is the richest source of beta-carotene, a natural source of pro-Vitamin A, and a great source of tocotrienols or Vitamin E. For refined red palm oil, the pro-Vitamin A carotene content is up to 15 times more than in carrots. Opportunities to supply consumers with a nutritionally beneficial blend based on red palm oil containing high levels of pro-Vitamin A beta-carotene and a potent level of antioxidant tocopherols and tocotrienols can only be offered by palm oil.

An estimated 80% of palm oil is used for food consumption. The CPOPC fully supports the importance of food security, adopting the global view that ‘no food means no human beings’. With high population growth, static agricultural land growth, and long-term effects of the pandemic, how will we secure the basic need of nutritious food for the world’s 10 billion human beings by 2050?

Addressing this challenge will require efficient and sustainable agri-food systems that are able to produce safe and adequate nutrients for everyone. No one should be left behind in accessing the fundamental right to food and to be free from hunger.

Opportunity to achieve UN goals

The oil palm is simple to grow because it is more efficient, uses less land, and needs less pesticides and fertilisers than other oilseed crops (Figure 2).

Palm oil is the best crop for cultivation in producer countries as it can be their vehicle to attain most of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 (Figure 3). Palm oil can help achieve13 of the 17 SDGs. As 40% of palm oil production is by smallholders, attaining the SDGs will also directly improve their economic and social welfare.

The attainment of the SDGs poses the challenge that palm oil production must itself be done sustainably. In this regard, producer countries are way ahead in organising the certified sustainable production of palm oil, compared to the non-existent or minimal capability for certified sustainable production of competing oils. Malaysia and Indonesia have each imposed mandatory certification of palm oil production, via the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) and Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) standard respectively.

At the time of writing, Malaysia had achieved 96% certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) production (Figure 4). This is reinforced by other certification schemes, giving buyers the option to choose what they prefer. In Indonesia, almost 6 million ha of plantations have been certified, including most of the large and state-owned plantations managed by companies.

Goal No. 12 of the SDGs highlights the need for sustainable production and consumption of food or edible oils and fats. CSPO supplies will deliver such benefits. In addition, trade in palm oil adds to economic growth, employment, food security and other SDG objectives in consuming countries. Thus, both producing and consuming countries can share the benefits.

Beating smear campaigns

There are not many challenges facing the palm oil industry which cannot be mitigated over time. The pandemic may have started the new trend of high prices for oils and fats. In the long term, the high prices may be attributed to supply growth limitations, resulting from the lack of new land for oil palm cultivation as a result of persistent anti-palm oil campaigns by NGOs.

It follows, though, that the actions of NGOs to discourage the expansion of oil palm cultivation have affected consumers, who pay higher prices for oils and fats. Palm oil producers are not much affected as they are well compensated when the price is high.

Similarly, European Union (EU) campaigns to ban the use of palm oil in its biofuel programme will have the unintended effect of causing greater environmental damage – the vegetable oils that will replace palm oil in biofuels will require much more land for their production. Palm oil producer countries, meanwhile, have built their biodiesel production and consumption capacity so that palm oil usage remains strong.

The situation has exposed the EU protectionist policy in trade, and palm oil producing countries are right in seeking to correct such unfair trade practices through complaints to the WTO. However, environmental lobbyists and some NGOs are expected to continue pressuring governments and corporate boards of palm oil consuming countries, particularly in the EU, to issue policies and initiatives that are counter-productive to opportunities offered by palm oil.

They continue to try to discredit palm oil by standing on the argument that it should be removed from the food supply chain (via the ‘no palm oil’ label) and substituted with other crops, using the unfounded allegation that oil palm cultivation causes deforestation. This dangerous and unrealistic scenario should be discontinued because the alternative crops are actually far behind oil palm on social, economic and environmental metrics.

Since the CPOPC was established in 2015, it has persisted in countering smear campaigns against palm oil. The CPOPC is and will be working closely with its current and future member-countries to maintain a sustainable supply chain in industry. Collective efforts will be strengthened with consuming countries to eliminate the trade-off between competing policy objectives and beating the smear campaigns against palm oil.

Palm oil is truly part of the solution and not part of the problem. Why? Because having this renewable resource guarantees that the world will always have a sustainable option to not run out of oil for nutrients, food and other purposes, not only for today but also future generations.

Tan Sri Datuk Dr Yusof Basiron

Executive Director, CPOPC,

Jakarta, Indonesia

This is an abridged version of the keynote address, ‘Overview of the World Palm Oil Industry Moving Forward: Challenges and Opportunities’, presented at the 2nd Edition of the World Palm Virtual Exhibition & Conference, on Sept 7, 2021. The full speech is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oR–1iS15j4&t=15s

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Markets No Comments

India approved its ambitious National Mission on Edible Oil-Oil Palm (NMEO-OP) in August 2021 to promote oil palm cultivation and help the country achieve self-sufficiency in edible oils. The NMEO-OP will be implemented over five years, from 2021-22 to 2025-26, with a special focus on the north-eastern states and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Markets No Comments

The second edition of MPOC’s Palm Oil Internet Seminar from Oct 18-24 was based on the theme ‘Determining Price Direction Amidst Market Uncertainties’. Among the topics covered by a panel of experts were CPO price forecasts; the global oil and fats supply outlook in 2021; palm oil supply and demand; the edible oils market in China and India; and opportunities for palm oil in Asia. A summary of three presentations follows.

‘Opportunities for Palm Products in Japan’s Renewable Energy Sector’

Hiroaki Goto

General Manager, EREX Singapore Limited

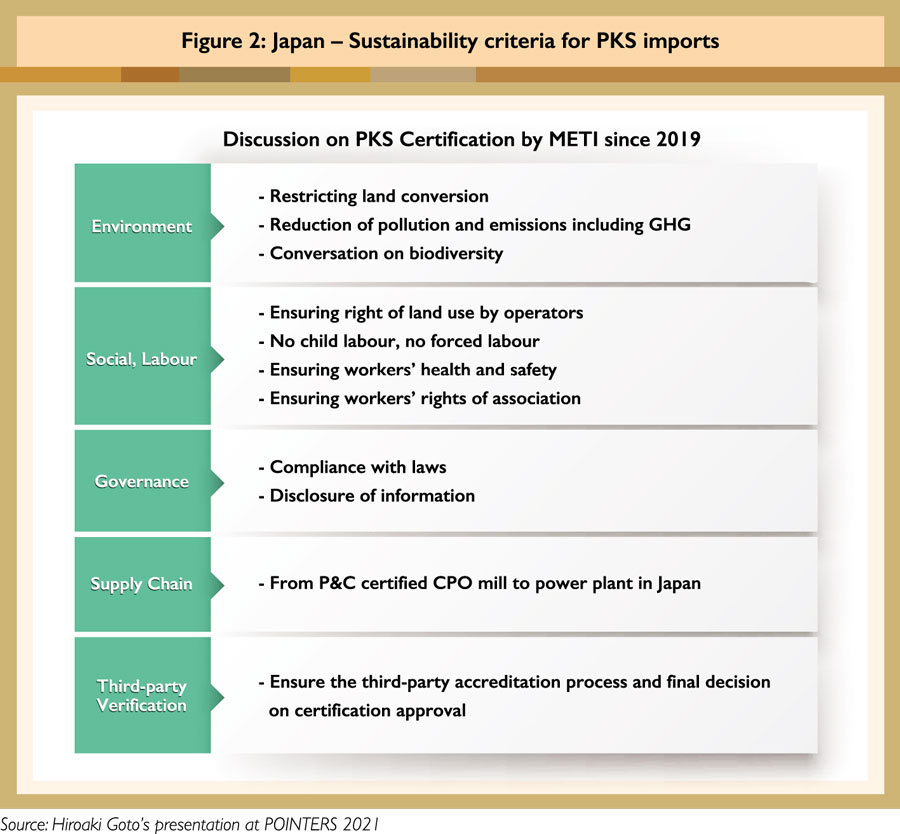

Following the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster in 2011, biomass has been increasingly used as a fuel source in Japan’s power plants. Palm kernel shell (PKS) is the preferred biomass, due to its narrow price gap with coal.

Japan has exponentially increased PKS imports since 2012, when biomass-generated electricity became eligible for the feed-in-tariff programme. Imports rose by 94% to record 3.3 million tonnes in 2020, up from 1.7 million tonnes in 2018. Indonesia is the main supplier of PKS, holding a market share of 73%. This was equivalent to 2.4 million tonnes in 2020.

Due to a significant increase in tax and levy by the Indonesian government, the price of PKS went up in 2020. This had a significant impact on the earnings of most of Japan’s power plants. Several buyers have since switched to Malaysian PKS or to wood pellets. Also due to the high price of PKS, plans for new power plants were cancelled or operations were postponed.

Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry has been discussing issues of the sustainability of PKS since 2019. Figure 2 illustrates the sustainability criteria that must be met for PKS to be imported. Only imports with the RSPO 2013/2018 certification and Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials certification have been accepted to date. The Japanese government is currently exploring acceptance of other certification standards, such as the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) and Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil schemes.

‘Opportunities for Certified Sustainable Malaysian Palm Oil in the Asian Market’

Mohammad Hafezh

CEO, Malaysian Palm Oil Certification Council (MPOCC)

The region’s trade plays a key role in boosting demand for sustainably produced palm oil. Malaysia is committed to ensuring that its palm oil industry adopts sustainable practices and offers fair market access to every industry player, from mega-plantation companies to smallholders. Under the MPOCC’s purview, efforts have been put in place to develop and implement sustainable palm oil production through the MSPO certification scheme. As at 2021, almost 90% compliance has been achieved. The focus is being expanded towards stepping up market acceptance, to demonstrate commitment to sustainable development and climate action.

‘MSPO Trace’ was launched in 2019 to enable end-users to trace the origin of the palm oil used in products, and to ensure transparency in sustainability management. As there is stronger commitment to sustainable sourcing by importing countries and companies, MSPO certification will provide a competitive edge in the uptake of certified sustainable palm oil.

In Japan, MSPO certification was recognised as proof of sustainability for the Olympics 2020 and Summer Paralympics. South Korea, which is in transition to a low-carbon economy, has set an ambitious target to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 37% by 2023, from the business-as-usual emission level. India and China, the two largest importers of palm oil, are moving towards sustainable palm oil trade with their own standards, such as the Indian Palm Oil Sustainability Framework.

At the same time, rapid economic growth and higher disposable income have led to changes in food consumption patterns in Vietnam and the Philippines; this has contributed to higher palm oil imports by the two countries.

‘Growth of Palm Oil Demand in the ASEAN Region in 2022 and Beyond’

Dr Julian McGill

Head of South East Asia, LMC International

ASEAN is one of the world’s most dynamic economic regions, with its member-states having experienced substantial GDP growth in recent years. Food consumption habits have changed with the availability of higher disposable income, as well as the rapid rate of urbanisation.

Consumption of vegetable oils has gone up in the region, particularly with the popularity of fast foods, snacks and processed foods. However, several countries, such as Cambodia and Laos, still have low levels of income; this translates to low vegetable oil calorie disappearance.

Palm oil dominates the consumption of oils and fats in the region (Figure 5), especially in Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, which are also major producers of the commodity.

Thailand and Vietnam have crushing facilities for soybean. As such, soybean oil is the main competitor of palm oil in these countries. Myanmar is the only country in the region that produces peanut oil. However, output is insufficient to meet the country’s oils and fats requirements.

Although the Philippines is the world’s largest coconut oil producer, palm oil dominates the share of oils and fats consumption in the country. Since 2005, coconut oil has been replaced by palm oil due to the wide price gap between both oils. Although the price gap between coconut oil and palm olein has narrowed to below US$100 since 2018, the volume of palm oil imports has remained consistent. This is attributed to consumer preference.

For the Philippines, coconut oil has become an export commodity due to its high market price compared to other edible oils. Additionally, the cyclical typhoon phenomenon disrupts the country’s supply of coconut oil; this has helped maintain the stability of palm oil imports.

The volume of palm oil imports by ASEAN member-states is expected to go up steadily due to the region’s growing population, increase in middle-class consumers and outstanding growth of the tourism sector.

Rina Mariati Gustam

& Nuradibah Mohd Razali

MPOC

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Markets No Comments

The second edition of MPOC’s Palm Oil Internet Seminar was held from Oct 18-24,2021. A panel of experts provided Oct 18-24, 2021. A panel of experts provided updated assesments on the global edible oils market, and reviewed the CPO price trend up to Q3 2021. They also shared insights into focus that may influence the price trend in Q4.

CPO prices rose sharply over Q1 and Q2 2021, spurred by the recovery of global edible oils demand. The palm oil industry benefitted from higher consumption, particularly by the hotel, restaurant and café sector worldwide; this had been drastically affected by the prolonged lockdown to curb the Covid-19 pandemic.

Strong demand was recorded from major palm oil importers like India, Iran, Turkey and Kenya, where stocks required replenishment. Demand also increased in Malaysia, due to celebration of the Muslim festival of Eid; a higher uptake of processed foods; and the soft reopening of industrial and business operations as the country emerged gradually from the lockdown.

In Q2, sentiments were affected by expectations of higher sunflower production in Ukraine and soybean output in the US. Another factor that contributed to price consolidation was speculation that Indonesia would cut its levy on CPO exports, which could lead to a larger outflow. Concerns over low stocks of CPO in Malaysia further influenced the trend of edible oil prices – in June, the stock level was below 1.7 million tonnes.

All four major oils had a consistently high value in Q3:

The price discount of soybean oil to palm oil in Q3 was US$250/tonne, an increase of US$81/tonne against the same period last year. The palm oil price sentiment was also affected by the seasonal peak production of oil palm from August to October.

Global edible oil prices began to recover in the final quarter of the year. The prospects of improved production of edible oils, especially sunflower oil, have been a significant driver. The price sentiment further turned positive on the news of lower Malaysian Palm Oil production, a weaker Ringgit and rising Brent crude oil prices.

Q4 2021 – Bullish factors

An array of bullish factors was observed to support the prospect of higher palm oil prices and bigger imports by major buyers.

China

Continued recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic and low inventories will drive imports of edible oils, including palm oil, in Q4 2021. Traders will likely import more palm olein due to lower domestic availability of soybean oil, as the poor breeding margin in the swine sector is expected to lower China’s soybean crushing activities. MPOC projects that China’s palm oil imports for the year will be 6.8 million tonnes, or 300,000 tonnes more than in 2020.

India

The country’s recent changes in import policy and duty cuts have contributed to the current price dynamics of palm oil. The removal of the ban on RBD palm olein imports from June to December 2021, and the reduction in import duty on all edible oils, are likely to push up India’s palm oil demand in Q4. The import duty reduction was aimed at bringing down edible oil prices which had risen by 14% in February and by 35% in June. MPOC estimates that India will import 8.7 million tonnes of palm oil for the year, compared to 1.2 million tonnes previously.

Malaysia

Palm oil production experienced a setback due to a severe shortage of labour. However, this is expected to have a positive impact on CPO prices. The production of Malaysian Palm Oil from January to September was recorded at 13.3 million tonnes, falling by 1.3 million tonnes (8.8%) against the same period last year.

MPOB expects Malaysian CPO production to decline to 18 million tonnes in 2021, or by 1.1 million tonnes (6%) year-on-year. As a result, MPOB forecasts that exports will drop by 6.2% over the comparative period. However, export revenue is anticipated to go up by 29.7% due to extremely high CPO prices particularly in the second half of 2021.

Q4 2021 – Bearish factors

The panel of experts also discussed factors which may have a bearish impact on price sentiments. Based on a forecast by Oil World’s Thomas Mielke, the US will have a bumper soybean crop in 2021, with production expected to rise by 6 million tonnes to 121 million tonnes. This may directly impact the CPO price rally recorded in October.

At the same time, it will be challenging for Indonesia – the world’s largest producer of palm-based biodiesel – to achieve its targeted output of about 7 million tonnes, if the FAME and Gasoil spread goes higher than INR5,000 per litre as at October.

Another bearish factor is a decline in palm oil imports by EU member-states. Several European governments have opted for early adoption of the revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED II), which will phase out palm oil use in biofuels by 2030. Austria, France, Belgium and Germany have adopted RED II ahead of implementation due from 2023. For 2021, MPOC forecasts that the EU will import about 7.8 million tonnes of palm oil, or about 400,000 tonnes less than the 2020 imports of 8.2 million tonnes.

CPO price sentiments in Q4 2021 may be affected by higher global output of oils and fats. For the 2021/22 season, Mielke predicts that global production will increase by 8 million tonnes – the biggest volume in the last four years. With this sizeable increase, edible oil stocks too will rise and subsequently weaken the CPO price.

The bearish factors may have an impact on CPO prices in the first quarter of 2022. However, several members of the expert panel predicted that the average CPO price will remain high until the end of 2021. MPOC projects CPO to trade within a range of RM3,517- 4,745/tonne, achieving an average of RM4,131/tonne for the year. MPOB puts its estimate at an average price of RM4,100/tonne.

As for the CPO price outlook for Q4 2021, Oil World is of the view that the current high prices of palm oil and other vegetable oils are not sustainable. However, should the South American soybean production prospects deteriorate significantly, the CPO prices have potential to remain high in the current price range. The weakening of the CPO price will be moderated by lower production in Malaysia.

Lim Teck Chaii

MPOC

Details of the presentation and discussion can be viewed at: www.pointers.org.my

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Comment No Comments

The European Union (EU), under its commitment to transparency, has improved avenues for stakeholders – both citizens and foreigners – to participate in its legislative and policy-making processes.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Comment No Comments

On July 16, 2021, the European Commission (EC) adopted its Communication on the New EU Forest Strategy (Forest Strategy) for 2030. The initiative is linked to the European Green Deal and builds on the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030.

The Forest Strategy recognises the central role of forests and the contribution of foresters and the entire forest-based value chain for achieving a sustainable and climate neutral economy by 2050. It reconfirms the EC’s commitment to forest management and deforestation-free supply chains, as set out in its 2019 Communication on Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests.

In the Biodiversity Strategy, which is the EU’s ‘comprehensive, ambitious and long-term plan to protect nature and reverse the degradation of ecosystems’, the EC notes that biodiversity loss and climate change require urgent action. On this basis, the EC set out to work on the Forest Strategy.

The Forest Strategy is also linked to the European Green Deal, which is characterised as a ‘growth strategy to transform the EU into a fairer and more prosperous society, with a modern, competitive, climate neutral and circular economy’.

Earlier in 2021, the EC held a public consultation on the Forest Strategy which, according to the relevant Roadmap, will focus on setting a policy framework to address ‘effective afforestation, forest preservation and restoration in Europe’.

While the Forest Strategy does not specifically refer to any implications for third countries, it makes reference to the EC’s Communication on Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests. This states: ‘EU consumption of food and feed products is among the main drivers of environmental impacts, creating high pressure on forests in non-EU countries and accelerating deforestation. Therefore, the consumption of products from deforestation-free supply chains in the EU should be encouraged both via regulatory and non-regulatory measures as appropriate.’

The core objective of the Forest Strategy is to help the EU to achieve:

The Forest Strategy recognises the central role of forests and the contribution of the forest-based value chain in achieving a sustainable and climate neutral economy by 2050. It sets out a policy framework aimed at delivering growing, healthy, diverse and resilient EU forests, which is intended to contribute significantly to the biodiversity ambition; secure livelihoods in rural areas and beyond; and support a sustainable forest bio-economy that relies on most sustainable forest management practices.

According to the Forest Strategy, forest management practices will be built ‘on a recognised and internationally agreed dynamic sustainable forest management concept that takes into account the multi-functionality, the variety of forests and the three inter-dependent pillars of sustainability’. Additionally, its annex provides for a Roadmap of action to plant 3 billion trees by 2030 in the EU.

Upcoming EU legislation

While the Forest Strategy focuses on EU forests, it reaffirms the EC’s commitment – made in its Communication to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests – to adopt legislation aimed at minimising the EU’s contribution to deforestation and forest degradation worldwide; and to promote the consumption of products from deforestation-free supply chains in the EU.

In 2020, the EC had published its Inception Impact Assessment for a legislative initiative on deforestation and forest degradation, and interested stakeholders provided initial feedback. A more detailed public consultation was held at the end of 2020.

The legislative proposal was published on Nov 17, 2021. Already in its Inception Impact Assessment, the EC had stated that one objective of the initiative is to promote the consumption of products from deforestation-free supply chains. The EC aims at introducing a due diligence system that would require businesses to ensure that their products, which are to be placed on the EU market, have not contributed to deforestation or forest degradation.

The legislative proposal on deforestation and forest degradation categorises countries as having a low, standard or high risk of deforestation and forest degradation. The categorisation will determine the respective due diligence obligations for companies selling products in the EU that originate in those countries.

In general terms, ‘simplified due diligence duties’ will apply to low-risk countries, while ‘enhanced scrutiny’ will be required for high-risk countries. However, the specific criteria for the classification remain unclear. In its proposal, the EC is limiting the scope of the requirements to six commodities – cattle, cocoa, coffee, oil palm, soybean and wood.

Public debate rarely makes a difference between sustainable and unsustainable palm oil production. More importantly, the oil palm is by far not the only agricultural commodity that should be considered in terms of the global environmental footprint – soybean, rapeseed, sunflower, canola, maize, sugar, beef and dairy production are arguably worse offenders and only some of those are covered by the EU’s proposal.

A report by the World Resources Institute states that deforestation on land used for oil palm cultivation has been decreasing since 2000; and that land use for cocoa and coffee has increased, while there has almost been no change for cattle farming.

As the EC itself has acknowledged, ‘deforestation and forest degradation are driven by many different factors’. This includes increased demand for food from a growing global population, feed, bioenergy and other commodities, ‘combined with low productivity and low resource efficiency’.

Partnership with producer countries?

Oil palm cultivation and its supply chain activities are extremely important for the economic and social well-being of Malaysia. The government remains committed to preserving its rich tropical forest coverage, as well as to sustainable cultivation of oil palm and the production of palm oil.

In 2019, the government capped the expansion of the oil palm cultivated area at 6.5 million ha, which effectively corresponds to a ban on new planting. Currently, the planted area covers 5.9 million ha. In addition, steps have been taken to ensure the sustainability of the oil palm sector, including implementation of mandatory certification for cultivators and palm oil producers under the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil standard.

At the same time, Malaysia has been stepping up action to protect forests and peatlands by further improving related laws and enforcement. Today, its forested area is estimated at almost 53% of the land area.

The New EU Forestry Strategy reaffirms the EC’s commitment to work ‘in close partnership with its global partners on forest protection, restoration and sustainable forest management’.

This commitment is also part of the Communication on Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests. In line with its development-cooperation principles, the EU intends to work in partnership with producer countries to fight deforestation and forest degradation.

It appears that the EU intends to achieve true partnerships with third countries, without any unilateral imposition of specific actions or measures, particularly those that do not appear to be scientifically justified, and which are proportionate and the least trade restrictive.

However, this is clearly not the case when it comes to biofuel feedstocks, where the EU has developed a trade-restrictive approach on indirect land use change. It also does not appear to be the case with the forthcoming legislative proposal on deforestation-free supply chains and related due diligence obligations.

Deforestation is a global issue that requires cooperation and multilateral solutions. More can be achieved through bilateral, plurilateral and/or multilateral cooperation than unilateral action, even if it is masked as ‘work in partnership’.

Malaysia’s commitment towards sustainability and forest conservation must be recognised and factored in when trade-related policies are defined and actions are taken by the EU. There needs to be effective partnership with Malaysia to define and adopt bilateral, plurilateral or multilateral standards and solutions for sustainable forestry and agricultural production compliance.

Malaysia and its palm oil industry should also be prepared to take a stand on the EU legislative proposal on deforestation and forest degradation. Engaging with the EU to define the scheme and conformity assessment procedures to certify Malaysia’s palm oil products as ‘deforestation-free’ would deliver comparative advantages vis-à-vis competitors, as well as eradicate the unfortunate image that the sector has endured in Europe.

The objective will require strategic thinking and planning; technical, commercial, scientific and diplomatic advocacy; and the commitment of human and financial resources on Malaysia’s part. It will also require the EU to truly engage in bilateral or multilateral negotiations.

The hope is that reason will prevail and that negotiated solutions can replace unilateral measures, trade irritants, dispute settlement proceedings and ineffective or partial solutions to the urgent problems of climate change mitigation, environmental protection and sustainability.

FratiniVergano

European Lawyers

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Cover Story No Comments

MPOC sat down with Malaysia’s new Plantation Industries and Commodities Minister, the Hon. Zuraida Kamaruddin, to discuss the state of the palm oil sector; opportunities for market expansion in Asia; ongoing global regulatory threats; and claims of forced and child labour on plantations.

Read more »