EU Trade Deals and Deforestation

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Comment No Comments

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Comment No Comments

A new World Wildlife Fund report, released around the same time as a sharp acceleration in Amazon deforestation, concludes that the rampant destruction of nature led to the Covid-19 pandemic – a view reinforced by the UN and WHO.

It also warns that future deforestation could unleash new global crises – from climate change to pandemics and biodiversity collapse.

That is why putting an end to deforestation once and for all must now be an urgent priority. The evidence confirms that relentless industrial expansion is consistently breaching the planetary boundaries necessary to maintain what scientists call a ‘safe operating space’ for humanity.

Thankfully, the EU’s trade balance gives it some leverage to tackle deforestation in a post-Covid world reeling from economic turmoil.

But merely boycotting problematic commodities implicated in deforestation won’t work – and often leads to the exports of those same commodities being redirected to regions with far lower environmental standards.

Indeed, the European Union (EU) has quietly conceded that its previous approach to stopping deforestation due to palm oil is unlikely to work.

A paper published by the European Parliament’s Directorate General for External Policies of the Union cites recent scientific studies on ‘deforestation linked to palm-oil production’ showing that solely reducing Europe’s own imports of palm oil is environmentally ineffective.

Instead, the paper concludes that ‘it is more effective and less costly if Malaysia and Indonesia’ – the world’s largest palm oil producers – ‘implement a moratorium on deforestation (targeting deforested areas)’.

This is because a palm oil boycott tends to simply switch demand to less efficient vegetable oils which use up more land, potentially driving greater rates of deforestation. It also signals to producer countries that adopting sustainable production methods is pointless because Europe doesn’t want to buy their palm oil anyway.

The question, of course, is how to incentivise developing nations to implement verifiable and effective forest conversation policies. A recent call in a report by the EU’s Agricultural Committee for new inclusive trade partnerships with the Global South attempts to address this issue.

The Committee warns that only mandatory, legally enforceable environmental standards can stop deforestation. But it also notes that such standards cannot be imposed unilaterally, and require buy-in from producer nations.

‘Stick and carrot’ approach

The big question missing from the EU’s ruminations so far is how to achieve this buy-in. There is one way: Working in partnership with the global south will mean adopting an aggressive ‘stick and carrot’ approach to trade deals.

Nations that meet environmental standards can be put on track for Free Trade Agreements. Those that refuse to do so would fall outside the negotiating table. That would be a huge step in spurring a global green economic revolution.

In Malaysia, there is now ample precedent for this process. The Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) standard is [a] national, government-mandated palm oil certification scheme enforceable by law.

Unlike voluntary schemes, like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil – catering for big corporate producers – the scheme is obligatory for all palm oil producers, more accessible to smallholder farmers, and enforced with fines for those who refuse to comply.

Unfortunately, the EU is still playing catch-up. The Directorate General report cites outdated research from last year to claim that in Malaysia and Indonesia, ‘attempts to limit palm oil-driven deforestation… fall short of their stated goals: less than one-third of palm oil production is certified, and often, certified areas overlap’.

But this is untrue. Since [the decision to make] the MSPO scheme mandatory, [ 71.1%] of oil palm plantations became certified as at the end of 2019. And Malaysia is aiming to certify 100% of its palm oil by the end of this year.

Further new research suggests that, in contrast to the Amazon where deforestation is accelerating, the MSPO scheme is working.

The World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch this month released new data showing that for three consecutive years, Malaysia’s rate of deforestation has slowed down – a development attributed to local ‘efforts to reduce deforestation’.

All this points to an unfortunate gap between EU perceptions and facts-on-the-ground, suggesting that the EU had rushed through its well-intended deforestation policies too haphazardly, without attention to key facts, and lacking sufficient engagement with countries who appear to be making real progress.

To be sure, we must not be sanguine. Rates of deforestation remain out of control, and if we do not act now, the Covid-19 crisis teaches us that human civilisation itself is in peril.

But the MSPO is one scheme showing that there is a path forward, one that might be scaled to other regions facing the scourge of deforestation. That is all the more reason the EU should find ways to work more closely with developing nations to support, rather than alienate, nationally-mandated conservation efforts.

This could help usher in a new global cooperative architecture that can cultivate trade in sustainable goods and services while using the full force of law to put an end to deforestation once and for all.

That may well avert the next global crisis.

Fazlun Khalid

Founder,

Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Sciences,

Birmingham, England

This is a slightly edited version of the article posted on July 10, 2020, at:

https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/opinion/eus-trade-deals-can-put-an-end-to-deforestation/

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Cover Story No Comments

The Hon. Dato’ Dr Khairuddin Aman Razali was appointed Malaysia’s Minister of Plantation Industries and Commodities in March, following the takeover of the government by Perikatan Nasional (PN) in February. In an interview, he highlights strategies to cope with ongoing issues in the palm oil sector, including challenges being thrown up by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Covid-19 has caused widespread suffering for oil palm smallholders, whose income has fallen due to the lower price of palm oil. How is your Ministry helping them?

Dato’ Dr Khairuddin Aman Razali: Smallholders have always been an important stakeholder in our palm oil industry. Over the years, the government has introduced various initiatives to help them succeed and improve their livelihood. To ease the impact of poor returns due to Covid-19, the government has allocated RM350 million in microcredit financing via Agrobank, at an interest rate of 3.5%, to help agropreneurs. This serves as another option for smallholders to finance plantation activities.

Currently, the Oil Palm Smallholder Replanting Financing Scheme and Oil Palm Smallholder Agricultural Input Scheme already assist smallholders with replanting old and unproductive oil palm trees with high yielding seedlings; in the long term, this will improve the yield and generate higher income.

Apart from that, the government is actively encouraging smallholders to participate in the Sustainable Oil Palm Planters Cooperative (KPSM). This aims to increase income through higher productivity via the implementation of Good Agricultural Practices and auxiliary activities. The main activity of the KPSM is the establishment of weighing centres to purchase fresh fruit bunches (FFB) from smallholders.

Under the 11th Malaysia Plan, the government has provided an incentive of RM200,000 per KPSM to build weighing centres. To strengthen capacity in FFB trading, the government – through the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) – has created a revolving fund for selected high performing KPSM. This serves as working capital support to offer a better price for FFB than that offered by middlemen dealers.

Through the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry, and working with MPOB, the government has launched the Cash Crop Programme for independent oil palm smallholders in the B40 [low-income] category; each participant gets RM3,000 to plant bananas and RM7,000 to plant pineapples. Additionally, an incentive scheme helps smallholders to venture into rearing livestock, such as cattle and goats, for extra income especially during a downturn in palm oil prices.

One main issue in the industry is the shortage of plantation workers. How do you see this impacting the industry, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic?

The labour shortage has affected productivity in all sectors. In the oil palm industry, there are vacancies in harvesting operations for about 36,000 people around the country. It is disheartening that some are reluctant to work in estates, and we have had no choice but to get in foreign workers. The problem was felt more acutely during the Covid-19 lockdown period earlier this year.

However, I look at this from a positive angle. The pandemic has made us realise how much we have been dependent on foreign workers. We need to woo more Malaysians to join the plantation sector. With many being laid off due to the economic impact of Covid-19, it would be good for them to seek employment in the plantation sector. We have implemented a minimum wage as stipulated by law. Some main industry players are currently paying double the amount, in addition to providing free accommodation and other perks. This information needs to be promoted more effectively to attract locals.

In trying to draw in the best workers, my Ministry has set up a special task force on plantation labour to see how best we can assist unemployed locals and match them with specific needs in the industry. The MPOB, meanwhile, remains very active in research and development to mechanise plantation activities. I truly believe that, through sheer determination and cooperation with all involved, Malaysia can address the shortage of workers. Further information can be obtained from MPOA and MPOB.

Since the PN took over the government, diplomatic ties with India have improved. Does this warmer relationship have any bearing on India’s intake of Malaysian palm oil?

I am glad that diplomatic ties between India and Malaysia have improved. The Right Honourable Prime Minister himself met with the Indian Envoy stationed in Kuala Lumpur. The improvement is evident in the increase in bilateral trade. We in the Ministry have also worked hard toward this.

The latest figures from the Department of Statistics show an increase in the value of exports of palm oil and its products by 544% in June (valued at RM633.5 million), compared to May (RM98.3 million). In June, India imported 246,045 tonnes of palm oil, compared to 10,806 tonnes in March – a 23-fold increase. We hope the trend will continue as the year progresses. My Ministry will work hard to ensure exports rise and to explore new markets.

Recently, I had a virtual discussion with H.E Singireddy Niranjan Redy, Minister of Agricultural, Co-operation, Marketing, Food & Civil Supplies, and Consumer Affairs in Telangana, India. I conveyed our hope that the Indian government will import more palm oil and palm-based products.

Mr Redy sought Malaysia’s expertise in oil palm cultivation to expand plantations in Telangana. I told him that the Malaysian government is willing to provide such expertise and that I hope India will provide sandalwood seedlings in exchange. Telangana is also impressed by our enthusiasm for the bamboo sector and has requested collaboration and possible investment by Malaysian companies.

Apart from that, my Secretary-General and his entourage paid a courtesy call on the High Commissioner of India to Malaysia. Their discussions focused on further improvement to diplomatic and trade relationships, especially in the commodities sector.

The European market has been hostile to palm oil, over alleged issues of sustainability and health. This shows that we cannot rely on a particular market to sell our palm oil. What do you have in mind to address this?

Palm oil has long been targeted because it is the most efficient oil-bearing crop in terms of production, land utilisation, pricing and versatility. This explains why the European Union (EU), as a main producer of rapeseed oil, is hostile to palm oil as a competing product. I am sad to note that the EU is reluctant to take into account our efforts toward sustainable production of palm oil, as well as communication with its parliamentarians and government officials. They continue to treat palm oil unfairly, so Malaysia has had no option but to seek action by the World Trade Organisation.

I agree that we cannot put all our eggs in one basket. We can target markets in the Middle East, Africa and Central Asia. They have a lot of potential that we can capitalise on, such as rising consumption from a growth in population.

Other than the Covid-19 pandemic, what factors have affected the demand for and price of Malaysian palm oil this year?

Firstly, many regard the trade war between the US and China as detrimental to the global economy due to the uncertainties created. When China agreed to buy more agricultural products from the US as part of their first trade deal signed in January, we anticipated that Chinese demand for Malaysian palm oil would be badly hit because of direct competition from soybean oil.

Indeed, our exports to China decreased by almost 16% in the first quarter of 2020, compared to the same period a year before. However, as tensions escalated between the two superpowers, we saw higher Chinese imports of our palm oil in the second quarter. It is hard to predict how the trade war will play out. We will monitor the situation closely and assess its impact on palm oil from time to time.

Secondly, restrictions on global and local travel to curtail Covid-19 have impacted the demand for biodiesel. Malaysia has delayed the implementation of its B20 programme until September for Sarawak and early next year for Sabah. As countries start to open their borders, I expect the demand for biodiesel to improve.

Thirdly, the breach in diplomatic ties between Malaysia and India did not help the palm oil industry. We lost quite a bit of exports during that period because India is our biggest buyer. But I believe we have mended this, as mentioned earlier.

Fourthly, we face continuous competition with other palm oil producers that could offer discounted prices. In dealing with this, my Ministry and its agencies have worked hard to maintain relationships with current buyers and to promote Malaysian palm oil to new ones.

The Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification scheme is a strategic approach by the government to enhance the competitiveness and marketability of Malaysian palm oil in the global market. What is the progress of the scheme, given the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic?

I have been involved in promoting the MSPO on the ground. At the events I attended, I sensed that awareness among smallholders with regard to the scheme and the necessity to get it implemented across the board has improved. They now understand why the government is serious about the scheme and why certification is mandatory. As at Aug 25, MSPO certification had been completed for about 86% or 5.1 million ha of the oil palm planted area.

While I am of course proud of this achievement, there is still much work to be done, particularly when it comes to certifying the independent smallholders. Collectively, 293,585 oil palm smallholders have received the MSPO certification. However, the majority are organised smallholders who are managed and certified under agencies such as FELDA and FELCRA.

We have only managed to certify 24.3% of the 986,331 ha of oil palm planted by independent smallholders. We will help to get them on board the MSPO through programmes such as Sustainable Palm Oil Clusters, to meet our target of 100% compliance with the scheme.

Recently, there was discussion that bamboo will replace palm oil as Malaysia’s top commodity. Was this a misunderstanding?

The debate on this in the Parliament was wrongly interpreted. At no point did I say that bamboo would replace palm oil as our main commodity. Our intention was merely to explore the economic viability of bamboo as an alternative commodity. The preliminary studies conducted locally have indicated that bamboo has the economic potential to generate lucrative income.

I would like to assure all palm oil stakeholders that the government will protect the interests of the industry and strengthen it. Among the measures being undertaken are application of the latest technology in the upstream sector; expansion of markets; diversification of value-added products; and studies that focus on the benefits of palm oil.

Can you tell us more about the ‘Sawit Anugerah Tuhan’ (‘Palm oil is God’s gift’) slogan that you have introduced?

When I was appointed Minister, I started to learn more about palm oil. I realised that palm oil, unlike competing oils, has many good qualities that warrant its status as the world’s leading vegetable oil. For example, its semi-solid characteristic at normal room temperature provides an effective solution to trans fats. It is highly versatile for various food applications. Palm oil is also nutritious and healthful as it is rich in potent antioxidants, Vitamin E and beta-carotene.

On the sustainability front, the oil palm is the most productive of oil crops, requiring the least acreage of land and inputs to produce the same tonnage of oil. There is also abundant and uninterrupted supply of palm oil for global consumption all year round. As such, I concluded that palm oil is a gift from God.

The slogan is an epitome of a product that has many attributes. It does not demean or belittle other commodities; it is an acknowledgement that palm oil is truly special. It is found in six out of 10 food and non-food products, and displayed on supermarket shelves in 160 countries. Can other commodities top that?

Finally, what are your wishes for Malaysian palm oil and the industry going forward?

Malaysia is one of the few net exporters of oils and fats. Therefore, it has a big role to play in helping to meet global food security. However, palm oil production is being linked to deforestation, carbon emissions, destruction of wildlife habitats, forced labour, violations of the rights of indigenous peoples, and food contamination. These claims are detrimental to the industry and can disrupt the global market access of palm oil.

Moving forward, I would like to see these issues being resolved for the benefit of all stakeholders. Here, we are addressing them through implementation of the MSPO standard; improved on-the-ground practices; and to some extent, branding. We also need to be more aggressive and effective in communications, and to work with concerned parties toward a common objective – the acceptance of sustainably produced palm oil.

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Markets No Comments

Uzbekistan is Central Asia’s biggest market both in terms of the economy and population. It is strategically located in the heart of the region, with a land border of more than 6,893 km with Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. Despite being a double-landlocked country, Uzbekistan has the unique advantage of being connected to all neighbouring states. This makes it a trade hub for the region.

Uzbekistan covers an area of 447,400 sq km and has a population of over 33 million. About 50% of the people live in urban areas like the cities of Tashkent, Samarkand, Namangan, Andijan and Navoi. The rate of urbanisation has slowed in recent years, while the rural population has been growing at a faster pace. Population growth rate has been maintained at 1.5% for the past few years; it is estimated that, at this rate, the population will exceed 41 million by 2050.

In September 2017, the government launched an ambitious economic reform plan which included unifying the exchange rate; liberalising the foreign exchange market; developing Free Economic Zones (FEZs); reducing tax rates and import duties; and simplifying business registration and operating procedures to attract foreign investors.

These measures are helping to address major issues that have restricted the growth of the private sector. Positive results are being seen in the key economic indicators. There has been a noticeable surge in investments and consumption, leading to a rise in the real GDP from 4.5% in 2017 to 5.1% in 2018 and a projected 5.3% in 2019.

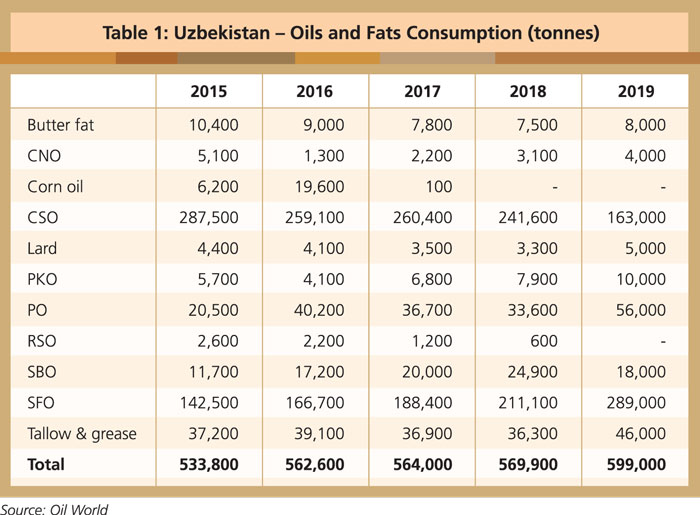

Uzbekistan has the largest edible oils market among the Central Asian Republics (CAR), both in terms of consumption and imports. Consumption stood at 599,000 tonnes in 2019 (Table 1), of which 56% was supplied locally. Demand has registered a steady average growth of 2.4% over the last five years. Per capita consumption of oils and fats now stands at 18kg.

Domestic production of edible oils and oilseeds recorded 339,000 tonnes in 2019, which was 2.5% lower than in 2018. Cottonseed oil, a by-product of the textile industry, was the largest oilseed crop, holding 53.3% of total production.

However, the government is placing less emphasis on the textile industry. Cottonseed oil consumption has therefore declined from 287,500 tonnes in 2015 to 163,000 tonnes in 2019. This reduction – as well as the rise in overall consumption of edible oils – will widen the gap between supply and demand and open the door to imports.

Sunflower oil is the most-consumed edible oil with a share of 48% of total consumption. Mainly used as a household premium cooking oil, it is largely imported from Russia, Kazakhstan and other Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Palm oil imports

Palm oil is the second-largest imported edible oil and is fast becoming a key ingredient in the confectionery and food industries. Imports have registered an impressive growth of 173% over the last five years, indicating its popularity in the food sector especially. The sector has seen double-digit growth over the last three years. Palm oil and its fractions are mainly used in the production of margarine, confectionery and ice cream.

Palm oil distribution in Uzbekistan is controlled by a few importers. They bring in supplies from Malaysia, Ukraine and Russia for local distribution. Direct purchases were previously restricted by the relatively small quantities required per month, as well as limited access to foreign currency. Since the 2017 economic reforms, more industry members are showing interest in buying directly from suppliers to get a better price, consistent quality and after-sales support.

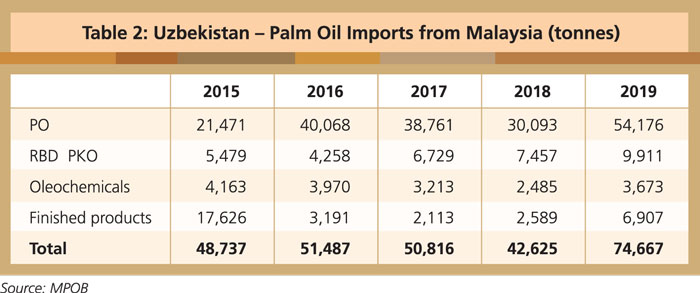

Malaysia is the largest supplier of palm oil and its fractions to Uzbekistan. Imports rose from 48,737 tonnes in 2015 to 74,667 tonnes in 2019 (Table 2).

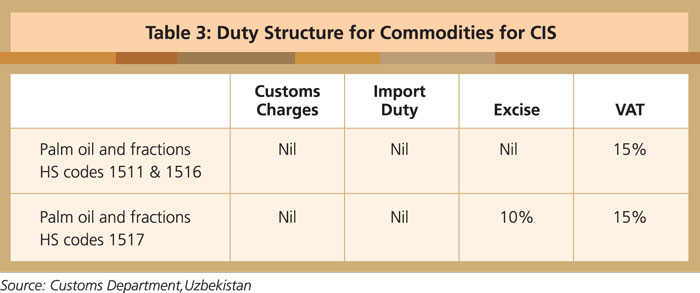

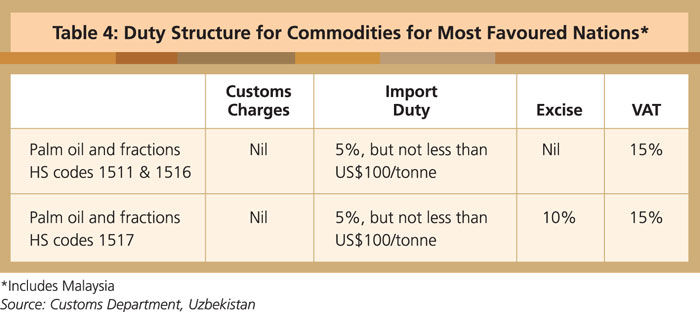

The import of palm oil had been heavily taxed, and Malaysian suppliers had to compete with suppliers in the CIS region who enjoyed a lower tax rate. In 2019, as part of the reduction of import duties on essential items, the government removed the import duty of 5% on palm oil fractions under HS code 1516 (hydrogenated oils). This resulted in a spike in the import of palm oil from Malaysia, from 42,625 tonnes in 2018 to 74,667 tonnes in 2019, or by 75%.

But this attracted a negative campaign by the region’s anti-palm oil lobbies, which was also picked up by some in the Uzbekistan government. In January 2020, the government again revised the duty structure on the import of oils and fats. All fractions of palm oil are now subject to 5% duty plus other applicable taxes.

Malaysian palm oil imports from January to June this year dropped to 29,474 tonnes compared to 31,031 tonnes over the same period in 2019, or by 5%. This was primarily because of the Covid-19 lockdown in all major cities of Uzbekistan.

Investment prospects

Uzbekistan holds strong potential for Malaysian palm oil in the CAR. With a long-term investment approach, it could become a hub for Malaysian palm oil exports to the entire CAR and CIS.

The government has developed seven special FEZs, with a wide range of tax breaks for investors. The FEZs offer exemptions from taxes (income tax and VAT), customs duties and taxes for goods imported for production and manufacturing needs, for a period of three to 10 years, depending on the quantum of investments. The government is encouraging foreign companies to establish processing plants to take advantage of tax breaks.

Malaysian palm oil industry players should capitalise on the investment opportunities, particularly in the downstream sector. The food industry, the primary user of palm oil, has shown consistent growth. Further growth can be achieved in the home cooking oil segment, which is currently dominated by sunflower oil.

Faisal Iqbal,

Deputy Director,

Marketing & Market Development; and

MPOC Pakistan

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Markets No Comments

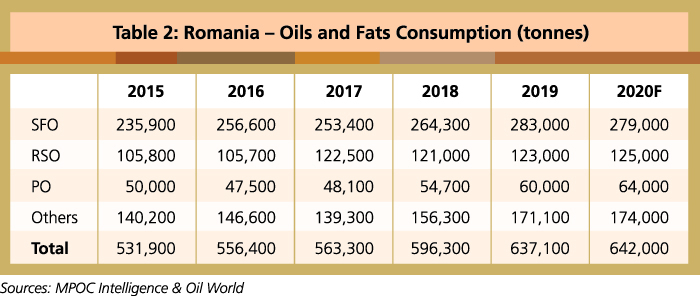

With a land area of almost 240,000 square km, Romania is the biggest country in the Balkans. It has become very much an industrial country since 2007, when the country joined the European Union (EU).

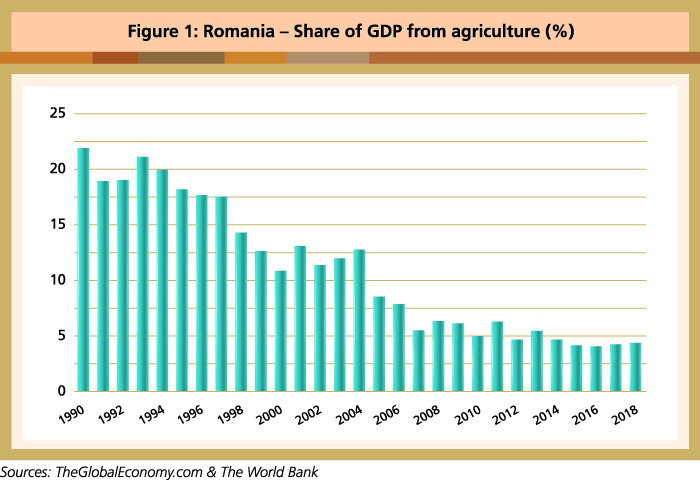

Of its agricultural land capacity of close to 15 million ha, only 10 million ha have been used as arable land. Agriculture contributed about 20% to the GDP in the 1990s (Figure 1), but this fell to 12.6% in 2004 and then to 4.3% in 2019. According to the Romanian Country Economic Memorandum (2020), income per capita increased from 26% of the EU-28 average in 2000 to 63% in 2017.

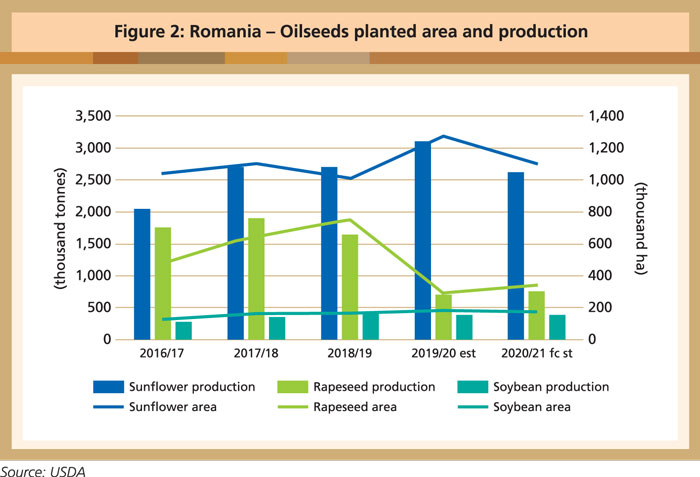

The planting of oilseeds utilises about 25% of the cultivated area, with sunflower accounting for the largest share, followed by rapeseed and soybean (Figure 2). Based on USDA data, the oilseed acreage is forecast to be lower by 7% this year due to a decline in sunflower planting. Year-on-year total oilseed production is forecast to fall by 10.7%.

Romania is the EU’s largest producer of sunflower seed, with the volume expanding by 26% in 2019/20. However, production is projected to contract by 13% in 2020/21 due to the lower profit margin and crop rotation. Exports are therefore expected to fall by 20%. Most of the sunflower seed will go to EU markets, with only about 15% bound for other destinations.

It is estimated that 400,000 ha were planted with rapeseed in the autumn of 2019 during exceedingly dry conditions. Of this, only about 340,000 ha remain under rapeseed, with the other 60,000 ha being diverted to spring crops. Drought over the winter and spring, as well as a damaging mid-March frost this year, could lead to a 7% decline in yield compared to 2019. Despite the lower planted area, rapeseed production is forecast at 750,000 tonnes, a 9.3% increase year-on-year.

Oils and fats market

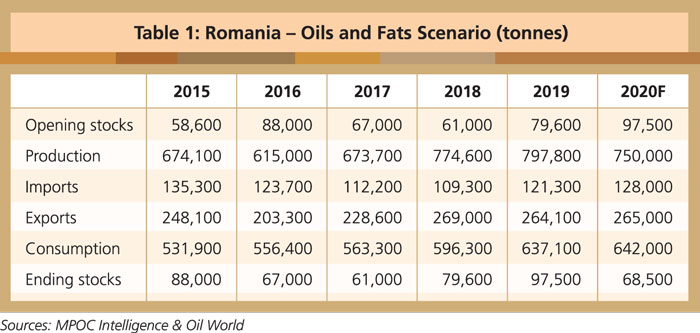

Romania is self-sufficient in terms of oils and fats production, and is even a net exporter. Annually it produces more than 700,000 tonnes of oils and fats, of which sunflower oil makes up 500,000 tonnes or 65% of total production. About 90% is exported to countries within the EU. Domestic consumption is recorded at 650,000 tonnes, mainly comprising sunflower and rapeseed oils at a combined 400,000 tonnes or 62% of the total.

The domestic market is pressed by low margins. Large players such as Prutul, Bunge, Ulerom, Ultex and Expur have invested in, or announced plans to invest, in biodiesel production as they expect the market to expand. The most significant players are Bunge, Argus, Cargill and Agricover.

Bunge has a share of about 36% in the edible oils market and operates two factories, Interoil Oradea and Unirea Iasi. Argus is the second-biggest player, holding about 20% of the market. Cargill, which has acquired Topway’s oil business including the Bunica brand, is currently ranked third but aims to take top spot in the industry.

Palm oil imports

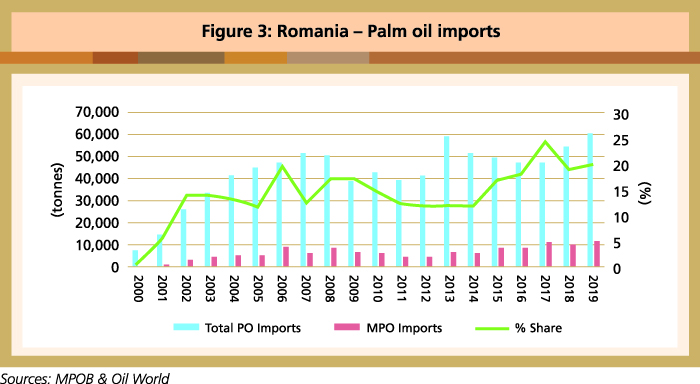

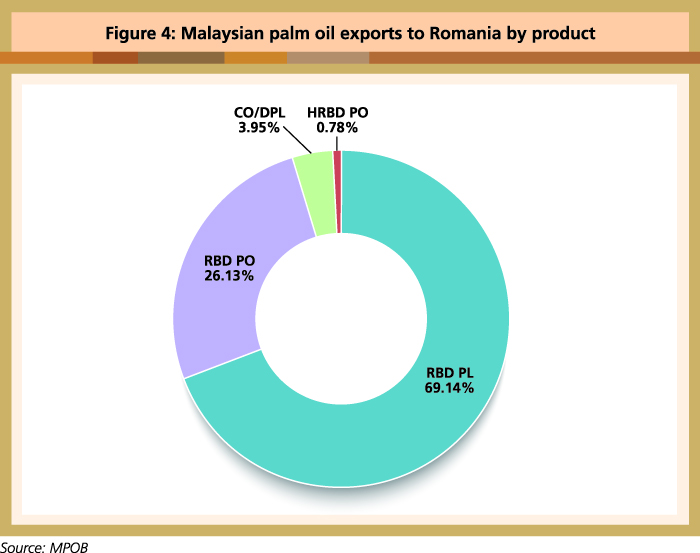

Romania imports more than 110,000 tonnes of oils and fats annually. Palm oil is the main product at close to 60,000 tonnes, or slightly more than 50% of total imports. It is also the third-most consumed vegetable oil behind sunflower oil and rapeseed oil. About 80% of the palm oil imports arrive via the Netherlands. Malaysia’s market-share stood at about 20% in 2019 (Figure 3).

Industrial users are the largest consumers of palm oil. Sectors like food manufacturing, chemicals, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals are all important in Romania’s economy and are potential customers for palm oil. Some large manufacturers already use palm oil in their production processes, as do restaurants and bread producers, among others in the food industry.

Almost all of the palm oil is consumed and there are no carryover stocks. With limited storage facilities within the country, users tend to purchase only what is needed. In 2019, Malaysia exported 12,104 tonnes of palm oil valued at RM37.1 million. RBD palm olein was the main product, for use in the prepared food industry (Figure 4).

In view of possible lower crushing of edible oilseeds, it is likely that Romania will import up to 300,000 tonnes of vegetable oils this year. Since the common EU foreign policy now applies for Romania, there are opportunities for Malaysian exporters who could consider exporting direct, rather than via a third country.

Storage capacity

Practically every farmer in Romania sells the oilseed crop at harvest time, as they lack adequate storage facilities. Even when storage is available, they cannot sufficiently control the self-heating phenomenon that affects oilseeds. Commercial storage capacity is limited and the prices are high. This is attributed to the quality of services provided and the regional monopoly that operators exert over competitors.

Oil factories also have limited storage facilities, and so they cap operations to a month at a time. Under long-term contracts, the operators get the silos – or send representatives to silos – to purchase sunflower seeds at harvest time. They pay for the seeds in the shortest time possible.

Port facilities and logistics

The Port of Constanta, located on the western coast of the Black Sea, is Romania’s main port. It occupies more than 3,900 ha and contains 156 berths, of which 140 are operational with a handling capacity of 100 million tonnes per year.

The facilities are comparable to those offered by most European and international ports, accommodating tankers with a capacity of up to 165,000 dwt and bulk carriers of up to 220,000 dwt. Several projects are underway to build facilities for cargo handling and to improve the transport connections between Constanta Port and its hinterland. These projects are mainly located at the southern end of the port.

Import procedures

As a member-state of the EU, Romania applies the standard procedures to the process of importing food-based products. The country’s food laws and regulations are also harmonised with EU legislation. Specific agencies are responsible for clearing shipments, depending on the category of products.

In respect of food and agricultural products, the agencies include the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development; Ministry of Environment; National Sanitary Veterinary and Food Safety Authority; Ministry of Health; and the National Authority for Consumer Protection.

Romania adopts the EU-level customs regime through Regulation 2013/952 of the European Parliament. Import duties are determined by the tariff classification of goods and by the Customs value. Other taxes applicable to agricultural and food products are the value added tax (VAT) and excises. Romania applies a reduced VAT rate of 9% to food products and agricultural inputs such as fertilisers and pesticides, and a standard VAT rate of 19% to other items.

Izham Hassan,

Manager,

Marketing & Market Development, MPOC

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Markets No Comments

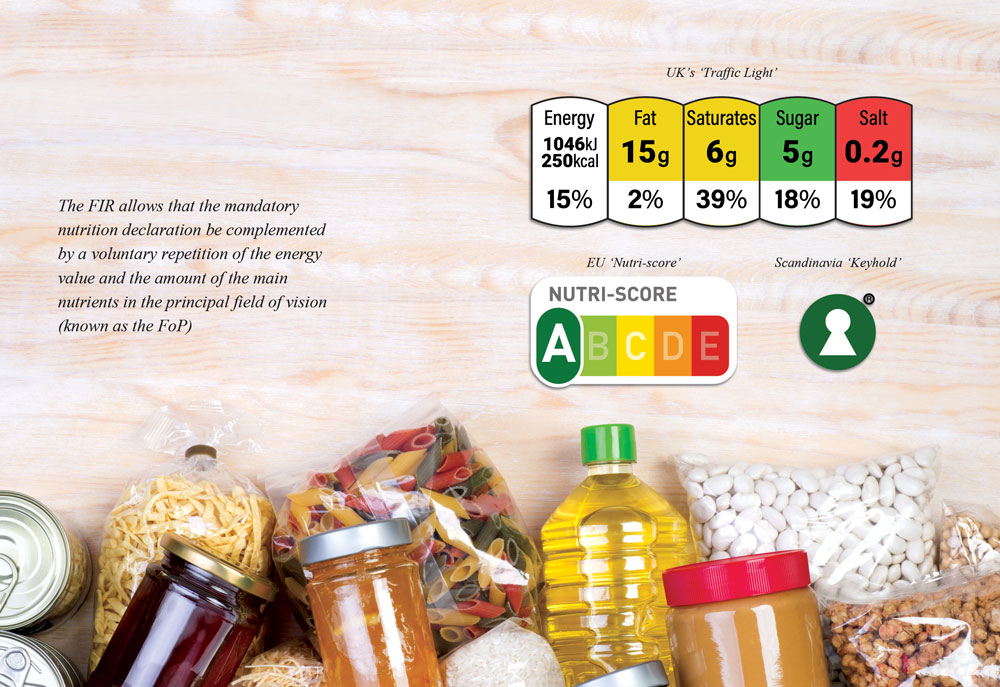

On May 20, 2020, the European Commission (EC), together with its Farm to Fork (F2F) Strategy ‘for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system’, published a report regarding the use of additional forms of the expression and presentation of the nutrition declaration on the Front-of-Pack (FoP) of food products. Certain FoP labelling schemes introduced in EU member-states in recent years can be considered as discriminating against particular foodstuffs or ingredients, including palm oil.

The EU’s Food Information Regulation (FIR) requires a nutrition declaration on the labelling of almost all pre-packaged foodstuffs. It demands that this label include the energy value, as well as the amounts of fat, saturates, carbohydrates, sugars, protein and salt (and, voluntarily, of mono-unsaturates, polyunsaturates, polyols, starch, fibre, and certain vitamins or minerals), expressed in tabular format (if space permits). This is to allow consumers to make informed and health-conscious choices. Prior to 2016, this nutrition declaration was voluntary, but when provided it had to adhere to a given format.

The FIR allows that the mandatory nutrition declaration be complemented by a voluntary repetition of the energy value and the amount of the main nutrients in the principal field of vision (known as the FoP), in order to help consumers see at a glance the essential nutrition information when purchasing foods. Such voluntary nutrition labelling may not be given in isolation, but must be provided in addition to the full mandatory (back-of-pack) nutrition declaration.

According to the FIR, additional forms of expression and/or presentation of the nutrition declaration may be used by operators or recommended by EU member-states, provided that they are objective, non-discriminatory and do not create obstacles to the free movement of goods. They must be based on sound and scientific research and should not mislead consumers, but aim at facilitating consumer understanding of the contribution or importance of the food product to the energy and nutrient content of a diet.

In various member-states and the UK, additional forms of FoP nutrition labels were introduced, such as the UK’s ‘traffic light’ scheme; the ‘Keyhole’ scheme developed in Scandinavian EU member-states and Norway; and the ‘Nutri-Score’ scheme in France and Belgium. Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg have also announced their decision to adopt the Nutri-Score scheme. Private operators have introduced their own schemes, such as the Reference Intakes Label, the Evolved Nutrition Label and the Healthy Choice logo.

In light of the experience gained with these additional forms of expression and/or presentation of the nutrition declaration, the FIR required the EC to adopt a report by Dec 13, 2017, on the use of FoP labels and their impact. Considering the limited experience in this area and recent developments at national level, the EC postponed the adoption of the report with a view to include the experience of recently introduced schemes.

Most importantly, and perhaps surprisingly, the EC’s report on FoP nutrition labelling goes beyond the scope of the FIR, which refers only to additional forms of expression and/or presentation, repeating the information provided in the nutrition declaration, and includes also ‘schemes that are providing information on the FoP on the overall nutritional quality of foods, since such a differentiation would not be pertinent from a consumer’s perspective’.

The EC notes in the report, that ‘some FoP schemes developed by member-states or food business operators do not repeat information provided in the nutrition declaration as such but provide information on the overall nutritional quality of the food (e.g. through a symbol or letter)’. On the basis of Article 36 of the FIR, the EC considers such schemes ‘as ‘voluntary information’ which shall nevertheless not mislead the consumer, not be ambiguous or confusing for the consumer and shall, where appropriate, be based on the relevant scientific data’.

Importantly, the EC notes that ‘at the same time, when such a scheme attributes an overall positive message (for example through a green colour), it also fulfils the legal definition of a ‘nutrition claim’ as it provides information on the beneficial nutritional quality of a food as defined in Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods’ (i.e. the EU’s Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation).

According to this regulation, claims are to be based on scientific evidence, must not be misleading, and are only permitted if the average consumer can be expected to understand the beneficial effects expressed by the claim. These requirements also apply to overall positive messages, such as green colours.

Nutri-Score scheme

In the report on FoP nutrition labelling, the EC discusses the Nutri-Score scheme in greater detail. Unlike ‘traffic light’ labels, which highlight key individual nutrients, the Nutri-Score system provides a single score for the entire product, giving consumers an overall assessment of the product at a glance. Nutri-Score gives a rating, based on algorithms, to any food (except single-ingredient foods and water) ranging from a dark green A (best) to a red E (worst), by weighing the prevalence of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ nutrients.

Some observers hoped that the EC would ‘endorse’ or ‘recommend’ the Nutri-Score scheme in its report and that it would become the ‘harmonised’ EU’s FoP nutrition labelling scheme. However, the EC remains neutral and simply states:

‘Nutri-Score, based on the UK Food Standards Agency nutrient profiling model, indicates the overall nutritional quality of a given food item. The label is represented by a scale of five colours, from dark green indicating food products with the highest nutritional quality to dark orange for products with lower nutritional quality, associated with letters from A to E. The algorithm to calculate the nutritional score considers both negative (sugars, saturated fats, salt and calories) and positive elements (protein, fibre, fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts).’

Schemes such as Nutri-Score appear to simply rank foods from ‘good’ to ‘bad’. A document of the French Ministry of Health of May 12, 2020, on frequently asked scientific and technical questions regarding Nutri-Score, describes more in detail the score calculation methods:

‘The score comprises two dimensions: positive points (corresponding to the ‘unfavourable’ components, an excess of which is considered unhealthy: calories, sugars, sodium and saturated fatty acids) and negative points (corresponding to ‘favourable’ components: fruits, vegetables, pulses, nuts and rapeseed, walnut and olive oils, protein and fibre, an adequate amount of which is considered healthy).’

The document provides a number of examples, one of which is particularly striking and applies to fried products, where the packaging indicates a fryer as a cooking method.

It is recommended that the producer informs consumers of the changes such a preparation method would cause in terms of the product’s Nutri-Score, by adding the following generic sentence:

‘When cooking in a fryer, the product’s Nutri-Score may vary by one letter if the frying oil is low in saturated fatty acids (sunflower or peanut oil), or by two letters if the frying oil used is very rich in saturated fatty acids (coconut, palm kernel or palm oil).’

Therefore, if a product has a ‘C’ Nutri-Score, if it is fried in palm oil, the consumer should attribute to it the worst outcome, notably the ‘E’ score. Thereby, Nutri-Score appears to clearly discriminate products containing saturated fats, like palm oil, which should not be discriminated per se, as they can also form part of a healthy diet, if consumed in moderation.

There are examples for the way in which Nutri-Score ‘judges’ different foods. The European Consumers Association (BEUC), in its publication ‘Five Nutri-Score myths busted’, addresses the myth that ‘Nutri-Score threatens the Mediterranean diet’, high in fruit, nuts, vegetable, legumes and cereals, low in red and processed meats and dairy products, and having olive oil as a major source of fat.

The BEUC states that this is all in line with Nutri-Score, and explicitly says that ‘with Nutri-Score, olive oil comes across as a source of good fat (‘C’) compared to butter (’E’) or saturates-rich vegetable oils such as palm oil (‘E’). Nutri-Score is helpful to make meaningful comparisons; for instance, it helps to compare various types of oils according to their saturated fat content (e.g. while butter, coconut and palm oils get an ‘E’, olive, walnut and rapeseed oils get a ‘C’)’.

Palm oil as an ingredient leads to a bad Nutri-Score. For instance, food business operator Nestlé is also supporting Nutri-Score and is implementing it on some of its products, including its famous KitKat chocolate bar, which, in addition to cocoa mass and butter, contains vegetable fats, including palm oil, palm kernel oil, and shea.

On its website, Nestlé indicates that KitKat receives a red ‘E’ Nutri-Score, but that ‘the Nutri-Score implementation will be done in a consistent way (…) regardless of the score of the product. It is a matter of transparency with consumers’. There are other examples. Reportedly, Ferrero’s Nutella would also receive the worst category label, a red Nutri-Score ‘E’ label. However, Ferrero does not display the still voluntary Nutri-Score.

In French and Belgian supermarkets, the Nutri-Score is already being displayed frequently on products. For example, Carrefour’s noisette chocolate spread containing rapeseed oil in a higher amount than cocoa butter, prominently displays a ‘palm oil-free’ label and states on its website that it achieves ‘a better’ brown ‘D’ Nutri-Score.

The same applies to Delhaize’s Choco, which is labelled to be ‘palm oil-free’ and contains sunflower oil, cacao butter and coconut fat. A brown ‘D’ Nutri-Score appears to be the best ranking a chocolate spread may get, but a number of brands are in fact putting an effort to achieve a ‘D’ and have already replaced palm oil with a more nutritionally favourable fat under Nutri-Score.

Here lies the danger. Palm oil-containing products, because of the higher content of saturated fats, receive bad Nutri-Scores; and manufacturers and supermarkets may be replacing palm oil with other vegetable oils, be it rapeseed or sunflower oil. This may not happen with famous and established brands like Nestlé’s KitKat or Ferrero’s Nutella.

However, there is a danger that, for alleged nutritional purposes and health-related marketing instruments like Nutri-Score, operators may be tempted or even forced by market pressure to eliminate palm oil from their products to compete with other products with a better Nutri-Score. This will most likely affect other product categories than just chocolate spreads, such as ready meals, cookies, toast or products that typically contain palm oil.

Shift in stance?

In the EU and its member-states, the idea of a complementary repetition of the energy value and the amount of nutrients on the FoP appears to be shifting towards an indication of the overall nutritional quality of food as the new standard. In the context of the F2F Strategy, the EC announced that a mandatory FoP nutrition labelling scheme would be proposed by the end of 2022.

It is important that the new mandatory FoP nutrition labelling scheme be more informative than schemes like the Nutri-Score, facilitating the understanding of the nutritional properties and not communicating an over-simplified ranking.

A mainly mathematical approach, on the basis of the composition of a very limited number of nutrients in order to formulate a ranking of the food, must be avoided. Naturally, such form of expression must be transparent, objective and non-discriminatory towards all products and ingredients, including palm oil, and allow the consumer to make an informed and unbiased decision.

The EC has further announced that, by the end of 2021, it would launch initiatives to stimulate the reformulation of processed foods, facilitating the shift to healthier diets. The setting of nutrient profiles to restrict the promotion of foods high in fat, sugars and/or salt is foreseen by the end of 2022.

These forthcoming initiatives must be carefully observed since some consider the presence of palm oil in processed food to be nutritionally disadvantageous. There appears to be a risk that EU nutrient profiles could discriminate against saturated fats, which may ultimately lead producers to reformulate products containing palm oil.

The EC’s FoP report addresses some schemes developed by EU private operators, but does not explicitly refer to ‘palm oil-free’ labels, which could be interpreted as a scheme informing that the vegetable oil, used in the respective product instead of palm oil, is nutritionally the better option. Such schemes may qualify as a scheme on the overall nutritional quality of foods. As ‘voluntary information’, such schemes must not mislead, may not be ambiguous or confusing, and must be based on relevant scientific data, where appropriate.

Interestingly, the EC stated in the F2F Strategy that it would also ‘support enforcement of rules on misleading information’. Enforcement of such rules is indeed needed as observed in the last years with respect to the nutritionally and environmentally misleading ‘palm oil-free’ labels and related denigratory campaigns.

The EU’s FoP Report and the F2F Strategy announce important forthcoming developments concerning food information and food composition. The palm oil sector and producing countries must be prepared to take part in the upcoming discussions and ensure that the chosen schemes and policies are not intentionally or accidentally damaging to palm oil.

FratiniVergano

European Lawyers

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Environment No Comments

The European Union (EU) has unilaterally stepped up action to ‘protect’ forests worldwide, without first sufficiently addressing deforestation in its own backyard. This is despite the fact that its forests account for just 38% of the total land area today.

The global forest area declined from 31.8% in 1990 to 30.8% in 2016. In contrast, Malaysia’s forests still cover about 55% of the land area. Following a decline of its forest area between 1990 and 2005, there was a laudable recovery by 2016 to the 1990 level due to action spearheaded by the government.

In July 2019, the European Commission (EC) adopted a ‘Communication on Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests’. This targets protecting and improving the health of forests, especially primeval forests, and significantly increasing sustainable, biodiverse forest cover worldwide. General priorities include:

Through its Communication, the EU has signalled its plan to ‘work in partnership’ with commodity producers in third countries to rein in deforestation and forest degradation. But does it have any intention to strive for true partnerships?

An earlier draft of the Communication had suggested the title ‘Cooperation and coordination with third countries’, adding that ‘building effective partnerships with producer countries in the tropical domain to support the uptake of sustainable agricultural and forestry practices’ should be a possible form of action.

However, the final text reads that ‘in line with EU development-cooperation principles, the EC will work in partnership with producing countries to fight deforestation and forest degradation’. The watered-down wording is indicative of a one-way approach in the plan of action.

Deforestation is a global issue that requires cooperation and multilateral solutions. Much more can be achieved through bilateral, plurilateral and/or multilateral cooperation than by unilateral action, even when masked as ‘working in partnership’.

Forest degradation in the EU

Recent examples show that the EU itself is not free of issues of deforestation and forest degradation. In 2016, the Polish government stepped up logging in the Białowieża Forest, one of Europe’s last primeval stands of woods. According to official information, 150,000 trees were felled in 2017 alone.

Operations were only halted when the European Court of Justice intervened in April 2018 because the forest is a UNESCO world heritage site. The Court found that the government had failed to fulfil its obligations to protect the forest, and ordered the immediate revocation of logging permits.

Another example is the primeval Hambach Forest in Germany, which is rich in biodiversity and home to species regarded as important for conservation purposes. Although the plan to cut down large parts of the remaining 10% of the forest for brown coal mining was suspended in 2018, the forest remains severely threatened by the expansion of the local brown coal mine.

In addition, data published in the journal Nature Research suggests that Europe has lost an immense area of forest to harvesting of timber. This significantly reduces the region’s carbon absorption capacity.

Many of the EU’s forests are managed for timber production, and thus harvested regularly. But according to satellite data, the loss of biomass (i.e. the total quantity or weight of organisms in a given area) increased by 69% from 2016-18, compared to 2011-15. Over the same period, the area of forest harvested increased by 49%.

This indicates that much more harvesting has occurred in a short period, even accounting for natural cycles and the impact of forest fires and heavy snowfall. The harvested area can normally be expected to vary by less than about 10% owing to cycles of planting and growing, and similar effects, according to the lead author of the study from the EU Joint Research Centre.

Other factors have contributed to the increase in harvesting, including higher demand for wood as a fuel and expansion of markets for timber and other wood products. The satellite data could be an early indicator of unsustainable demands on the EU’s forests. The loss of forest biomass from 2016-18 was most pronounced in Sweden, which accounted for 29% of the rise in harvesting, and Finland (22%).

There are other threats to the EU’s forests. In May this year, dramatic developments of forest damage and the threat of a ‘Forest Extinction 2.0’ were reported in Germany. This refers to a forest crisis in the 1980s, due to acid rain caused by air pollution. Notably the result of acid-forming exhaust gases, it was one of several factors behind a destructive effect on forests. The situation had prompted intense public debate – termed ‘Forest Extinction’ – across Europe.

Climate change has had a drastic impact on forests in different parts of Germany. In particular, conifer species like pine and spruce suffer because of extreme conditions such as heat, drought and storms. In Bavaria and other Federal States, more and more pine trees are dying in the deeper and warmer locations. The black pine species which, until now, had been considered heat resistant, has also been affected. About 80% of the largest black pine stand in Würzburg district has been damaged.

Where the fault lies

The Communication cites a 2016 report by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation that ‘agricultural expansion for the production of commodities (e.g. soybean, beef, palm oil, coffee, cocoa) drives about 80% of all deforestation specifically in tropical countries, while mining, urbanisation and infrastructure are responsible for less than 10% each’.

Soybean cultivation and beef production have been shown to have a far greater impact on forests, the climate and the environment than the oil palm – which has been a constant target of EU trade and environmental policies. Soybean currently covers an area that is six times larger than that under oil palm. The expansion of livestock production for beef is also a key cause of deforestation.

In Latin America, 70% of the forested land in the Amazon region has been converted to pasture. Recent reports note that up to 80% of deforestation in the Amazon can be attributed to the cattle ranching sector. In 2017, the estimated remaining forest cover in the Brazilian Amazon region was 3,316,172 sq km, or only 80.9% of the forest cover recorded in 1970. At the current rate of deforestation, by 2030, the Amazon rainforest will be reduced by as much as 40%.

Cultivation of feed crops, such as soybean, cover a large part of the remaining 30% of once-forested land in the Amazon. Brazil, the world’s largest producer of soybean, has quadrupled production over the last two decades and is expected to add to this over the next 10 years. Notably, pig farmers in the EU, the world’s largest exporter of pork, depend on Brazilian soybean for feed.

Beef production is considered the biggest driver of tropical deforestation worldwide – being responsible for more than twice that caused by the production of soybean, palm oil and wood products combined. It is estimated that the deforestation for cattle ranching alone releases 340 million tonnes of carbon to the atmosphere annually, equivalent to 3.4% of current global emissions.

The EU is, in part, responsible for the deforestation in Brazil – 20% of Brazil’s beef and soybean exports to the EU is produced on land that was illegally deforested, according to a report published in Science magazine on July 16, 2020.

The study – led by authors from Brazil, Germany and the US – used a special software to analyse 815,000 rural properties and identify areas where illegal deforestation associated with soybean and beef production is taking place in the Amazon and Cerrado – the vast tropical savanna in the centre of Brazil – and how much of these products is for the EU.

The authors also made an estimate of greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation that is linked to soybean and beef exports. They further pointed out the shared culpability of international buyers: “Between 18% and 22% – possibly more – of annual exports from Brazil to the EU are the fruit of illegal deforestation,” said lead author Raoni Rajão, a professor at Brazil’s University of Minas Gerais in Belo Horizonte.

According to official data, a record 3,700 sq km of the Amazon were deforested in the first half of this year, up 25% from the same period in 2019. The report noted ‘the responsibility of all foreign markets in this process’.

Deforestation by the Brazilian agriculture industry ‘destroys the forest to gratify the European appetite’, said the authors, adding that ‘two million [tonnes] of soy[bean] grown on illegally deforested land reaches the EU each year’.

No rhetoric – clearly, the facts speak for themselves.

Uthaya Kumar

Regional Director

MPOC Brussels

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Comment No Comments

As someone who has worked for the palm oil industry during exciting and challenging times, I must say it remains a dynamic one. However, it has continued to attract global attention for the wrong reasons.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Comment No Comments

As countries across the globe continue to grapple with the impact of the pandemic, and struggle to meet their economic and social obligations, the UK government has proposed a new law that will put further pressure on businesses.

New requirements recently announced in the UK could increase the cost of doing business, at a time when most economies are still trying to get COVID-19 under control, and putting in place measures to address the economic damage to many sectors and businesses.

The UK government, on 25th August, announced plans to introduce a new law to ensure that the supply chains of companies, and the products they sell, are free from illegal deforestation.

This is to ensure that consumer countries allow only legal commodities into their markets.

The proposal would prohibit larger businesses operating in the UK from using products grown on land that was deforested illegally.

This means companies will be responsible to ensure that their products were produced in line with local laws protecting forests and other natural ecosystems, as outlined by the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA).

To achieve this, businesses would be required to carry out due diligence on their supply chains, and publish information to show where the key commodities – such as cocoa, rubber, soy and palm oil – came from, and that they were produced in line with these local laws.

Seven key commodities have been identified under the proposal – beef and leather, cocoa, palm oil, pulp and paper, rubber, soya and timber.

Businesses that fail to comply would face fines, with the amount to be determined later.

The UK government has begun a 6-week online consultation to seek views from stakeholders on whether it should introduce the new law.

According to DEFRA the proposed law would:

Larger businesses will be targeted, as they are considered to be influential, and able to send a positive signal to producers.

Elena Polisano, forests campaigner at Greenpeace UK, said: “DEFRA’s proposal to make it ‘illegal for larger businesses to use products unless they comply with local laws to protect natural areas’ is seriously flawed.

“We will never solve this problem without tackling demand. Companies like Tesco, which sells more meat and dairy, and so use more soya for animal feed than any other UK retailer, know what they need to do to reduce the impact they are having on deforestation in the Amazon and other crucial forests”. (Ecologist, 25 August 2020)

“They must reduce the amount of meat and dairy they sell, and drop forest destroyers from their supply chains immediately.”

The new proposed law comes after the Global Resource Initiative (GRI) – the Government’s independent taskforce – was set up last year to see how the UK could ‘green’ international supply chains and reduce the footprint on the global environment by slowing the loss of forests.

The taskforce’s report stated that supply chain transformations were required for the UK’s own imports and consumption of seven key commodities – beef and leather, cocoa, palm oil, pulp and paper, rubber, soya and timber.

It called on the UK to take urgent action to ensure that the production, trade and consumption of agricultural and forestry products have a positive impact on people and the planet by:

Sir Ian Cheshire, chair of the independent taskforce, said that every day, British consumers buy food and other products which contribute to the loss of the world’s most precious forests.

He said the UK needs to find ways of reducing this impact if the country wants to tackle climate change, reduce the risks of pandemics, and protect the livelihoods of some of the world’s poorest people. (The Grocer, 25 Aug 2020)

In the past, similar measures were seen in the timber sector, under the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Action Plan, the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR), which came into effect in March 2013. The EUTR prohibits illegal timber and paper products from entering the European market, also via a due diligence system.

EU plans to introduce mandatory supply chain due diligence

As part of the European Commission’s (EC) 2021 work plan and the European Green Deal, the EU plans to also introduce legislation on mandatory supply chain due diligence for EU companies – as announced by the European Commissioner for Justice, Didier Reynders . This is to ensure that sustainability is embedded into the corporate governance framework.

This announcement followed a study commissioned by the EC, examining due diligence requirements through the supply chain.

The study concluded that the introduction of mandatory due diligence requirements would yield the greatest positive impact. A key finding of the study was that any new law should be cross-sectoral and applicable to all businesses, regardless of size.

The mandatory due diligence requirement would involve a legal mechanism, which imposes a “legal standard of care”. This means the due diligence carried out by a business should be objectively

sufficient in order to discharge its duty.

In other words, the proposal is “outcome-based”, rather than a procedural approach. No liability would be imposed if the business can show it undertook reasonable due diligence.

This development will require businesses to reinforce their compliance programmes and apply greater focus on these areas, including in the context of supply chain and other business relationships, and M&A and financing arrangements. (EC Study on due diligence requirements through the supply chain).

To mitigate reputational risks and meet the higher standards requested by consumers and investors, businesses have been taking their own initiatives to prevent or minimise their human rights or environmental impact by conducting training, having contractual clauses, codes of conduct and/or audits.

Even though companies have been voluntarily reporting requirements on due diligence, there is a push for a legal landscape as opposed to corporate reporting, owing to concerns over the quality of these due diligence processes.

Corporate reporting is considered insufficient to gauge actual practices carried out by the companies, as there are claims that these could be merely reactive responses to external pressure from NGOs or media campaigns.

While audits and certification schemes are common in commodity sectors, there are concerns that this approach could be limited, as it may not address the actual identified risks and actions taken to mitigate.

Audit and certification schemes usually only provide information about whether a supplier ‘passed’ or ‘failed’ an audit against a defined standard, rather than shedding light on what risks were identified, and how these can be mitigated.

These schemes also focus on what has happened during the past year, rather than considering what could happen in the future, and how emerging risks can be addressed.

An approach that focuses on the future – rather than past – is considered to be far better in mitigating risks.

The certification approach has been used for many agricultural products, but there are claims that it fails to deal adequately with the sector’s environmental and social problems.

There is now growing interest in parts of the agricultural sector, to look at how to better link the certification of products with legislative proposals.

Other challenges include the cost of certification, which often disproportionately falls on smaller businesses and producers, such as small farmers.

Although there are certification schemes in place, such as the RSPO, ISCC, MSPO, and ISPO in the palm oil sector, NGOs have been pushing for more stringent rules as they consider the schemes to have not adequately addressed environmental and social problems.

The stringent requirements often touted by NGOs would eventually increase the cost of doing business, making it difficult for commodities to compete in the global market.

Frustration is mounting amongst commodity producers, as rules are being selectively imposed to protect local producers from competition.

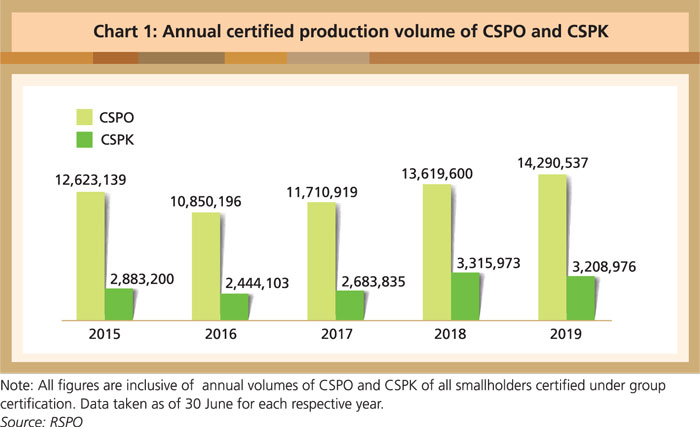

In addition, not all certified sustainable palm oil has found a market. Although there has been a healthy growth in production of certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) demand remains lukewarm.

Due to the supply and demand imbalanced, only 50% of CSPO oil is taken up. Ultimately, it makes no business sense to keep increasing production costs, due to new requirements, if this is not met with sufficient market demand.

Although it is in the interest of the commodity sector to meet market expectations, this must be compensated with sufficient profits for the time, effort and costs incurred to ensure supply chains are certified sustainable.

All sectors understand the need to sell high quality products that meet consumer demand, but only with sufficient profits, funds can be ploughed back into the business, and practices can be further improved. This is in the interest of producers, buyers, as well as consumers.

One could argue that the proposed new law is meant to ensure that companies step up their efforts to buy CSPO oil, or end up paying a heavy penalty.

However, why should, for example, palm oil producers face such scrutiny when they have kept their side of the bargain by adhering to certification requirements? It is the buyers who have not kept to their promise.

The new rules emerging from either the EU or the UK sends a strong signal to producers that Europe will continue to impose new barriers to the export of palm oil.

Sustainability clauses will likely become a norm in trade negotiations.

The EU is emerging as a global rule maker and sustainability standard setter. The rules set by the EU will eventually also be practiced globally, and will have an impact on palm oil producing countries. Once these rules or standards are endorsed, they will become global standards.

In this instance, it also looks like the UK and the EU are both competing to set global sustainability standards, which could disadvantage commodity-producing countries that have invested time and resources in ensuring that their supply chains are fully certified according to local laws.

If this continues, producer countries will lose interest in these markets as the cost of doing business increases. After all, cost remains a significant factor in any business, especially during the current challenging business environment.

Introducing a due diligence obligation puts the UK at the fore front for establishing legislation for products that they consider as a threat to forests.

But it also signals that both the UK and the EU are competing to be global trend setters for sustainability regulations.

It is imperative that Malaysia moves to ensure that the MSPO scheme meets these new requirements.

It is equally important that producers seek a long term assurance that local schemes, that have received support from small farmers, are recognised and supported.

With commodity producers going through a tough time, importing countries should find ways to strengthen local schemes to meet their requirements, rather than to keep re-inventing the wheel and adding further pressure and costs.

This is especially important for food commodity sectors, as they are essential for satisfying the increasing needs of consumers worldwide.

Belvinder Sron

Deputy CEO, MPOC