UK's proposed law will raise cost of doing business in Europe, in the midst of a global pandemic

October, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Comment

As countries across the globe continue to grapple with the impact of the pandemic, and struggle to meet their economic and social obligations, the UK government has proposed a new law that will put further pressure on businesses.

New requirements recently announced in the UK could increase the cost of doing business, at a time when most economies are still trying to get COVID-19 under control, and putting in place measures to address the economic damage to many sectors and businesses.

The UK government, on 25th August, announced plans to introduce a new law to ensure that the supply chains of companies, and the products they sell, are free from illegal deforestation.

This is to ensure that consumer countries allow only legal commodities into their markets.

The proposal would prohibit larger businesses operating in the UK from using products grown on land that was deforested illegally.

This means companies will be responsible to ensure that their products were produced in line with local laws protecting forests and other natural ecosystems, as outlined by the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA).

To achieve this, businesses would be required to carry out due diligence on their supply chains, and publish information to show where the key commodities – such as cocoa, rubber, soy and palm oil – came from, and that they were produced in line with these local laws.

Seven key commodities have been identified under the proposal – beef and leather, cocoa, palm oil, pulp and paper, rubber, soya and timber.

Businesses that fail to comply would face fines, with the amount to be determined later.

The UK government has begun a 6-week online consultation to seek views from stakeholders on whether it should introduce the new law.

According to DEFRA the proposed law would:

Larger businesses will be targeted, as they are considered to be influential, and able to send a positive signal to producers.

Elena Polisano, forests campaigner at Greenpeace UK, said: “DEFRA’s proposal to make it ‘illegal for larger businesses to use products unless they comply with local laws to protect natural areas’ is seriously flawed.

“We will never solve this problem without tackling demand. Companies like Tesco, which sells more meat and dairy, and so use more soya for animal feed than any other UK retailer, know what they need to do to reduce the impact they are having on deforestation in the Amazon and other crucial forests”. (Ecologist, 25 August 2020)

“They must reduce the amount of meat and dairy they sell, and drop forest destroyers from their supply chains immediately.”

The new proposed law comes after the Global Resource Initiative (GRI) – the Government’s independent taskforce – was set up last year to see how the UK could ‘green’ international supply chains and reduce the footprint on the global environment by slowing the loss of forests.

The taskforce’s report stated that supply chain transformations were required for the UK’s own imports and consumption of seven key commodities – beef and leather, cocoa, palm oil, pulp and paper, rubber, soya and timber.

It called on the UK to take urgent action to ensure that the production, trade and consumption of agricultural and forestry products have a positive impact on people and the planet by:

Sir Ian Cheshire, chair of the independent taskforce, said that every day, British consumers buy food and other products which contribute to the loss of the world’s most precious forests.

He said the UK needs to find ways of reducing this impact if the country wants to tackle climate change, reduce the risks of pandemics, and protect the livelihoods of some of the world’s poorest people. (The Grocer, 25 Aug 2020)

In the past, similar measures were seen in the timber sector, under the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Action Plan, the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR), which came into effect in March 2013. The EUTR prohibits illegal timber and paper products from entering the European market, also via a due diligence system.

EU plans to introduce mandatory supply chain due diligence

As part of the European Commission’s (EC) 2021 work plan and the European Green Deal, the EU plans to also introduce legislation on mandatory supply chain due diligence for EU companies – as announced by the European Commissioner for Justice, Didier Reynders . This is to ensure that sustainability is embedded into the corporate governance framework.

This announcement followed a study commissioned by the EC, examining due diligence requirements through the supply chain.

The study concluded that the introduction of mandatory due diligence requirements would yield the greatest positive impact. A key finding of the study was that any new law should be cross-sectoral and applicable to all businesses, regardless of size.

The mandatory due diligence requirement would involve a legal mechanism, which imposes a “legal standard of care”. This means the due diligence carried out by a business should be objectively

sufficient in order to discharge its duty.

In other words, the proposal is “outcome-based”, rather than a procedural approach. No liability would be imposed if the business can show it undertook reasonable due diligence.

This development will require businesses to reinforce their compliance programmes and apply greater focus on these areas, including in the context of supply chain and other business relationships, and M&A and financing arrangements. (EC Study on due diligence requirements through the supply chain).

To mitigate reputational risks and meet the higher standards requested by consumers and investors, businesses have been taking their own initiatives to prevent or minimise their human rights or environmental impact by conducting training, having contractual clauses, codes of conduct and/or audits.

Even though companies have been voluntarily reporting requirements on due diligence, there is a push for a legal landscape as opposed to corporate reporting, owing to concerns over the quality of these due diligence processes.

Corporate reporting is considered insufficient to gauge actual practices carried out by the companies, as there are claims that these could be merely reactive responses to external pressure from NGOs or media campaigns.

While audits and certification schemes are common in commodity sectors, there are concerns that this approach could be limited, as it may not address the actual identified risks and actions taken to mitigate.

Audit and certification schemes usually only provide information about whether a supplier ‘passed’ or ‘failed’ an audit against a defined standard, rather than shedding light on what risks were identified, and how these can be mitigated.

These schemes also focus on what has happened during the past year, rather than considering what could happen in the future, and how emerging risks can be addressed.

An approach that focuses on the future – rather than past – is considered to be far better in mitigating risks.

The certification approach has been used for many agricultural products, but there are claims that it fails to deal adequately with the sector’s environmental and social problems.

There is now growing interest in parts of the agricultural sector, to look at how to better link the certification of products with legislative proposals.

Other challenges include the cost of certification, which often disproportionately falls on smaller businesses and producers, such as small farmers.

Although there are certification schemes in place, such as the RSPO, ISCC, MSPO, and ISPO in the palm oil sector, NGOs have been pushing for more stringent rules as they consider the schemes to have not adequately addressed environmental and social problems.

The stringent requirements often touted by NGOs would eventually increase the cost of doing business, making it difficult for commodities to compete in the global market.

Frustration is mounting amongst commodity producers, as rules are being selectively imposed to protect local producers from competition.

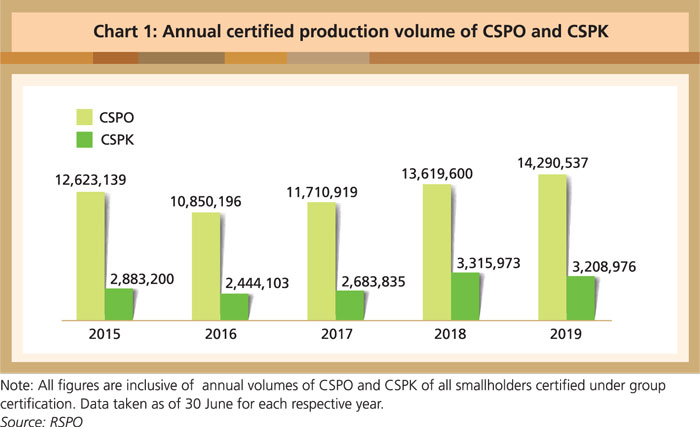

In addition, not all certified sustainable palm oil has found a market. Although there has been a healthy growth in production of certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) demand remains lukewarm.

Due to the supply and demand imbalanced, only 50% of CSPO oil is taken up. Ultimately, it makes no business sense to keep increasing production costs, due to new requirements, if this is not met with sufficient market demand.

Although it is in the interest of the commodity sector to meet market expectations, this must be compensated with sufficient profits for the time, effort and costs incurred to ensure supply chains are certified sustainable.

All sectors understand the need to sell high quality products that meet consumer demand, but only with sufficient profits, funds can be ploughed back into the business, and practices can be further improved. This is in the interest of producers, buyers, as well as consumers.

One could argue that the proposed new law is meant to ensure that companies step up their efforts to buy CSPO oil, or end up paying a heavy penalty.

However, why should, for example, palm oil producers face such scrutiny when they have kept their side of the bargain by adhering to certification requirements? It is the buyers who have not kept to their promise.

The new rules emerging from either the EU or the UK sends a strong signal to producers that Europe will continue to impose new barriers to the export of palm oil.

Sustainability clauses will likely become a norm in trade negotiations.

The EU is emerging as a global rule maker and sustainability standard setter. The rules set by the EU will eventually also be practiced globally, and will have an impact on palm oil producing countries. Once these rules or standards are endorsed, they will become global standards.

In this instance, it also looks like the UK and the EU are both competing to set global sustainability standards, which could disadvantage commodity-producing countries that have invested time and resources in ensuring that their supply chains are fully certified according to local laws.

If this continues, producer countries will lose interest in these markets as the cost of doing business increases. After all, cost remains a significant factor in any business, especially during the current challenging business environment.

Introducing a due diligence obligation puts the UK at the fore front for establishing legislation for products that they consider as a threat to forests.

But it also signals that both the UK and the EU are competing to be global trend setters for sustainability regulations.

It is imperative that Malaysia moves to ensure that the MSPO scheme meets these new requirements.

It is equally important that producers seek a long term assurance that local schemes, that have received support from small farmers, are recognised and supported.

With commodity producers going through a tough time, importing countries should find ways to strengthen local schemes to meet their requirements, rather than to keep re-inventing the wheel and adding further pressure and costs.

This is especially important for food commodity sectors, as they are essential for satisfying the increasing needs of consumers worldwide.

Belvinder Sron

Deputy CEO, MPOC