The EU mulls the proposal

October, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Markets

On May 20, 2020, the European Commission (EC), together with its Farm to Fork (F2F) Strategy ‘for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system’, published a report regarding the use of additional forms of the expression and presentation of the nutrition declaration on the Front-of-Pack (FoP) of food products. Certain FoP labelling schemes introduced in EU member-states in recent years can be considered as discriminating against particular foodstuffs or ingredients, including palm oil.

The EU’s Food Information Regulation (FIR) requires a nutrition declaration on the labelling of almost all pre-packaged foodstuffs. It demands that this label include the energy value, as well as the amounts of fat, saturates, carbohydrates, sugars, protein and salt (and, voluntarily, of mono-unsaturates, polyunsaturates, polyols, starch, fibre, and certain vitamins or minerals), expressed in tabular format (if space permits). This is to allow consumers to make informed and health-conscious choices. Prior to 2016, this nutrition declaration was voluntary, but when provided it had to adhere to a given format.

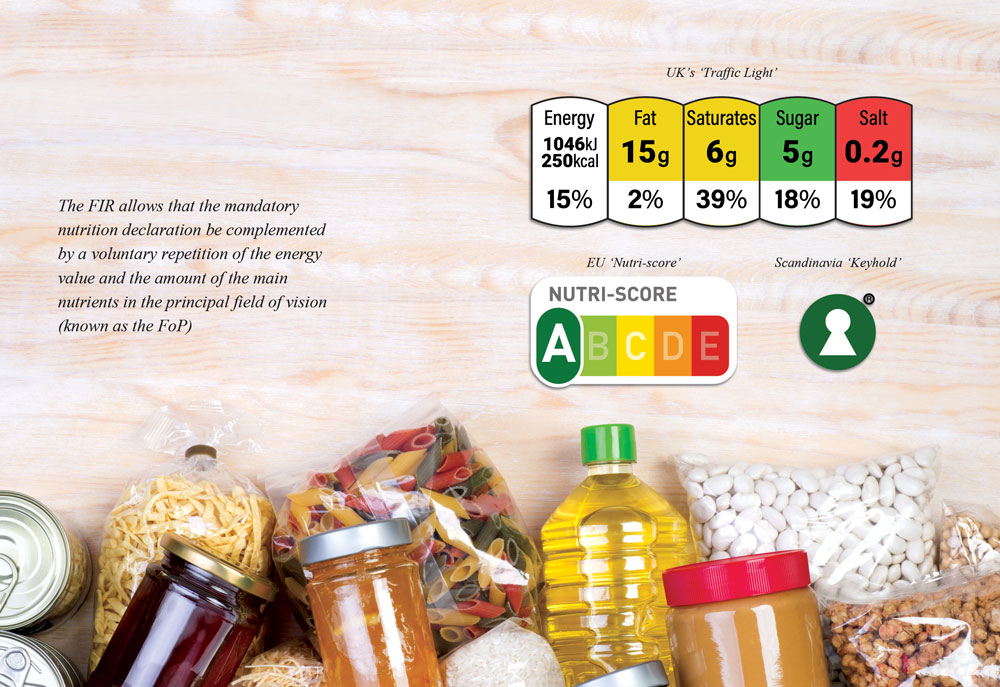

The FIR allows that the mandatory nutrition declaration be complemented by a voluntary repetition of the energy value and the amount of the main nutrients in the principal field of vision (known as the FoP), in order to help consumers see at a glance the essential nutrition information when purchasing foods. Such voluntary nutrition labelling may not be given in isolation, but must be provided in addition to the full mandatory (back-of-pack) nutrition declaration.

According to the FIR, additional forms of expression and/or presentation of the nutrition declaration may be used by operators or recommended by EU member-states, provided that they are objective, non-discriminatory and do not create obstacles to the free movement of goods. They must be based on sound and scientific research and should not mislead consumers, but aim at facilitating consumer understanding of the contribution or importance of the food product to the energy and nutrient content of a diet.

In various member-states and the UK, additional forms of FoP nutrition labels were introduced, such as the UK’s ‘traffic light’ scheme; the ‘Keyhole’ scheme developed in Scandinavian EU member-states and Norway; and the ‘Nutri-Score’ scheme in France and Belgium. Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg have also announced their decision to adopt the Nutri-Score scheme. Private operators have introduced their own schemes, such as the Reference Intakes Label, the Evolved Nutrition Label and the Healthy Choice logo.

In light of the experience gained with these additional forms of expression and/or presentation of the nutrition declaration, the FIR required the EC to adopt a report by Dec 13, 2017, on the use of FoP labels and their impact. Considering the limited experience in this area and recent developments at national level, the EC postponed the adoption of the report with a view to include the experience of recently introduced schemes.

Most importantly, and perhaps surprisingly, the EC’s report on FoP nutrition labelling goes beyond the scope of the FIR, which refers only to additional forms of expression and/or presentation, repeating the information provided in the nutrition declaration, and includes also ‘schemes that are providing information on the FoP on the overall nutritional quality of foods, since such a differentiation would not be pertinent from a consumer’s perspective’.

The EC notes in the report, that ‘some FoP schemes developed by member-states or food business operators do not repeat information provided in the nutrition declaration as such but provide information on the overall nutritional quality of the food (e.g. through a symbol or letter)’. On the basis of Article 36 of the FIR, the EC considers such schemes ‘as ‘voluntary information’ which shall nevertheless not mislead the consumer, not be ambiguous or confusing for the consumer and shall, where appropriate, be based on the relevant scientific data’.

Importantly, the EC notes that ‘at the same time, when such a scheme attributes an overall positive message (for example through a green colour), it also fulfils the legal definition of a ‘nutrition claim’ as it provides information on the beneficial nutritional quality of a food as defined in Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods’ (i.e. the EU’s Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation).

According to this regulation, claims are to be based on scientific evidence, must not be misleading, and are only permitted if the average consumer can be expected to understand the beneficial effects expressed by the claim. These requirements also apply to overall positive messages, such as green colours.

Nutri-Score scheme

In the report on FoP nutrition labelling, the EC discusses the Nutri-Score scheme in greater detail. Unlike ‘traffic light’ labels, which highlight key individual nutrients, the Nutri-Score system provides a single score for the entire product, giving consumers an overall assessment of the product at a glance. Nutri-Score gives a rating, based on algorithms, to any food (except single-ingredient foods and water) ranging from a dark green A (best) to a red E (worst), by weighing the prevalence of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ nutrients.

Some observers hoped that the EC would ‘endorse’ or ‘recommend’ the Nutri-Score scheme in its report and that it would become the ‘harmonised’ EU’s FoP nutrition labelling scheme. However, the EC remains neutral and simply states:

‘Nutri-Score, based on the UK Food Standards Agency nutrient profiling model, indicates the overall nutritional quality of a given food item. The label is represented by a scale of five colours, from dark green indicating food products with the highest nutritional quality to dark orange for products with lower nutritional quality, associated with letters from A to E. The algorithm to calculate the nutritional score considers both negative (sugars, saturated fats, salt and calories) and positive elements (protein, fibre, fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts).’

Schemes such as Nutri-Score appear to simply rank foods from ‘good’ to ‘bad’. A document of the French Ministry of Health of May 12, 2020, on frequently asked scientific and technical questions regarding Nutri-Score, describes more in detail the score calculation methods:

‘The score comprises two dimensions: positive points (corresponding to the ‘unfavourable’ components, an excess of which is considered unhealthy: calories, sugars, sodium and saturated fatty acids) and negative points (corresponding to ‘favourable’ components: fruits, vegetables, pulses, nuts and rapeseed, walnut and olive oils, protein and fibre, an adequate amount of which is considered healthy).’

The document provides a number of examples, one of which is particularly striking and applies to fried products, where the packaging indicates a fryer as a cooking method.

It is recommended that the producer informs consumers of the changes such a preparation method would cause in terms of the product’s Nutri-Score, by adding the following generic sentence:

‘When cooking in a fryer, the product’s Nutri-Score may vary by one letter if the frying oil is low in saturated fatty acids (sunflower or peanut oil), or by two letters if the frying oil used is very rich in saturated fatty acids (coconut, palm kernel or palm oil).’

Therefore, if a product has a ‘C’ Nutri-Score, if it is fried in palm oil, the consumer should attribute to it the worst outcome, notably the ‘E’ score. Thereby, Nutri-Score appears to clearly discriminate products containing saturated fats, like palm oil, which should not be discriminated per se, as they can also form part of a healthy diet, if consumed in moderation.

There are examples for the way in which Nutri-Score ‘judges’ different foods. The European Consumers Association (BEUC), in its publication ‘Five Nutri-Score myths busted’, addresses the myth that ‘Nutri-Score threatens the Mediterranean diet’, high in fruit, nuts, vegetable, legumes and cereals, low in red and processed meats and dairy products, and having olive oil as a major source of fat.

The BEUC states that this is all in line with Nutri-Score, and explicitly says that ‘with Nutri-Score, olive oil comes across as a source of good fat (‘C’) compared to butter (’E’) or saturates-rich vegetable oils such as palm oil (‘E’). Nutri-Score is helpful to make meaningful comparisons; for instance, it helps to compare various types of oils according to their saturated fat content (e.g. while butter, coconut and palm oils get an ‘E’, olive, walnut and rapeseed oils get a ‘C’)’.

Palm oil as an ingredient leads to a bad Nutri-Score. For instance, food business operator Nestlé is also supporting Nutri-Score and is implementing it on some of its products, including its famous KitKat chocolate bar, which, in addition to cocoa mass and butter, contains vegetable fats, including palm oil, palm kernel oil, and shea.

On its website, Nestlé indicates that KitKat receives a red ‘E’ Nutri-Score, but that ‘the Nutri-Score implementation will be done in a consistent way (…) regardless of the score of the product. It is a matter of transparency with consumers’. There are other examples. Reportedly, Ferrero’s Nutella would also receive the worst category label, a red Nutri-Score ‘E’ label. However, Ferrero does not display the still voluntary Nutri-Score.

In French and Belgian supermarkets, the Nutri-Score is already being displayed frequently on products. For example, Carrefour’s noisette chocolate spread containing rapeseed oil in a higher amount than cocoa butter, prominently displays a ‘palm oil-free’ label and states on its website that it achieves ‘a better’ brown ‘D’ Nutri-Score.

The same applies to Delhaize’s Choco, which is labelled to be ‘palm oil-free’ and contains sunflower oil, cacao butter and coconut fat. A brown ‘D’ Nutri-Score appears to be the best ranking a chocolate spread may get, but a number of brands are in fact putting an effort to achieve a ‘D’ and have already replaced palm oil with a more nutritionally favourable fat under Nutri-Score.

Here lies the danger. Palm oil-containing products, because of the higher content of saturated fats, receive bad Nutri-Scores; and manufacturers and supermarkets may be replacing palm oil with other vegetable oils, be it rapeseed or sunflower oil. This may not happen with famous and established brands like Nestlé’s KitKat or Ferrero’s Nutella.

However, there is a danger that, for alleged nutritional purposes and health-related marketing instruments like Nutri-Score, operators may be tempted or even forced by market pressure to eliminate palm oil from their products to compete with other products with a better Nutri-Score. This will most likely affect other product categories than just chocolate spreads, such as ready meals, cookies, toast or products that typically contain palm oil.

Shift in stance?

In the EU and its member-states, the idea of a complementary repetition of the energy value and the amount of nutrients on the FoP appears to be shifting towards an indication of the overall nutritional quality of food as the new standard. In the context of the F2F Strategy, the EC announced that a mandatory FoP nutrition labelling scheme would be proposed by the end of 2022.

It is important that the new mandatory FoP nutrition labelling scheme be more informative than schemes like the Nutri-Score, facilitating the understanding of the nutritional properties and not communicating an over-simplified ranking.

A mainly mathematical approach, on the basis of the composition of a very limited number of nutrients in order to formulate a ranking of the food, must be avoided. Naturally, such form of expression must be transparent, objective and non-discriminatory towards all products and ingredients, including palm oil, and allow the consumer to make an informed and unbiased decision.

The EC has further announced that, by the end of 2021, it would launch initiatives to stimulate the reformulation of processed foods, facilitating the shift to healthier diets. The setting of nutrient profiles to restrict the promotion of foods high in fat, sugars and/or salt is foreseen by the end of 2022.

These forthcoming initiatives must be carefully observed since some consider the presence of palm oil in processed food to be nutritionally disadvantageous. There appears to be a risk that EU nutrient profiles could discriminate against saturated fats, which may ultimately lead producers to reformulate products containing palm oil.

The EC’s FoP report addresses some schemes developed by EU private operators, but does not explicitly refer to ‘palm oil-free’ labels, which could be interpreted as a scheme informing that the vegetable oil, used in the respective product instead of palm oil, is nutritionally the better option. Such schemes may qualify as a scheme on the overall nutritional quality of foods. As ‘voluntary information’, such schemes must not mislead, may not be ambiguous or confusing, and must be based on relevant scientific data, where appropriate.

Interestingly, the EC stated in the F2F Strategy that it would also ‘support enforcement of rules on misleading information’. Enforcement of such rules is indeed needed as observed in the last years with respect to the nutritionally and environmentally misleading ‘palm oil-free’ labels and related denigratory campaigns.

The EU’s FoP Report and the F2F Strategy announce important forthcoming developments concerning food information and food composition. The palm oil sector and producing countries must be prepared to take part in the upcoming discussions and ensure that the chosen schemes and policies are not intentionally or accidentally damaging to palm oil.

FratiniVergano

European Lawyers