Uzbekistan is Central Asia’s biggest market both in terms of the economy and population. It is strategically located in the heart of the region, with a land border of more than 6,893 km with Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. Despite being a double-landlocked country, Uzbekistan has the unique advantage of being connected to all neighbouring states. This makes it a trade hub for the region.

Uzbekistan covers an area of 447,400 sq km and has a population of over 33 million. About 50% of the people live in urban areas like the cities of Tashkent, Samarkand, Namangan, Andijan and Navoi. The rate of urbanisation has slowed in recent years, while the rural population has been growing at a faster pace. Population growth rate has been maintained at 1.5% for the past few years; it is estimated that, at this rate, the population will exceed 41 million by 2050.

In September 2017, the government launched an ambitious economic reform plan which included unifying the exchange rate; liberalising the foreign exchange market; developing Free Economic Zones (FEZs); reducing tax rates and import duties; and simplifying business registration and operating procedures to attract foreign investors.

These measures are helping to address major issues that have restricted the growth of the private sector. Positive results are being seen in the key economic indicators. There has been a noticeable surge in investments and consumption, leading to a rise in the real GDP from 4.5% in 2017 to 5.1% in 2018 and a projected 5.3% in 2019.

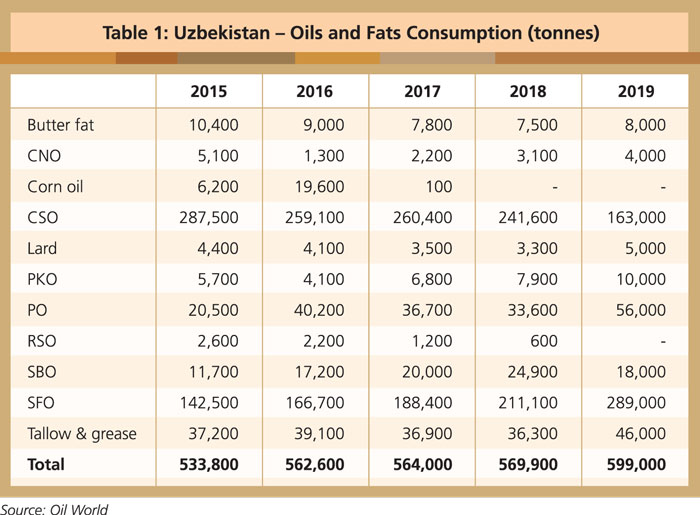

Uzbekistan has the largest edible oils market among the Central Asian Republics (CAR), both in terms of consumption and imports. Consumption stood at 599,000 tonnes in 2019 (Table 1), of which 56% was supplied locally. Demand has registered a steady average growth of 2.4% over the last five years. Per capita consumption of oils and fats now stands at 18kg.

Domestic production of edible oils and oilseeds recorded 339,000 tonnes in 2019, which was 2.5% lower than in 2018. Cottonseed oil, a by-product of the textile industry, was the largest oilseed crop, holding 53.3% of total production.

However, the government is placing less emphasis on the textile industry. Cottonseed oil consumption has therefore declined from 287,500 tonnes in 2015 to 163,000 tonnes in 2019. This reduction – as well as the rise in overall consumption of edible oils – will widen the gap between supply and demand and open the door to imports.

Sunflower oil is the most-consumed edible oil with a share of 48% of total consumption. Mainly used as a household premium cooking oil, it is largely imported from Russia, Kazakhstan and other Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Palm oil imports

Palm oil is the second-largest imported edible oil and is fast becoming a key ingredient in the confectionery and food industries. Imports have registered an impressive growth of 173% over the last five years, indicating its popularity in the food sector especially. The sector has seen double-digit growth over the last three years. Palm oil and its fractions are mainly used in the production of margarine, confectionery and ice cream.

Palm oil distribution in Uzbekistan is controlled by a few importers. They bring in supplies from Malaysia, Ukraine and Russia for local distribution. Direct purchases were previously restricted by the relatively small quantities required per month, as well as limited access to foreign currency. Since the 2017 economic reforms, more industry members are showing interest in buying directly from suppliers to get a better price, consistent quality and after-sales support.

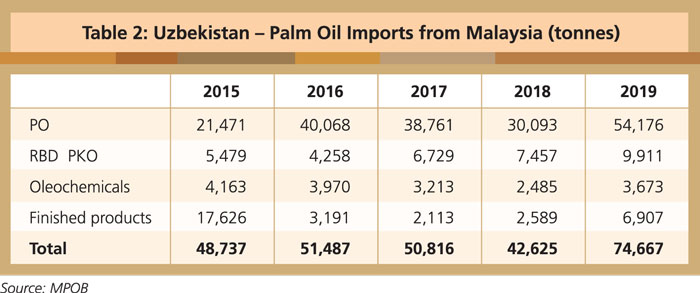

Malaysia is the largest supplier of palm oil and its fractions to Uzbekistan. Imports rose from 48,737 tonnes in 2015 to 74,667 tonnes in 2019 (Table 2).

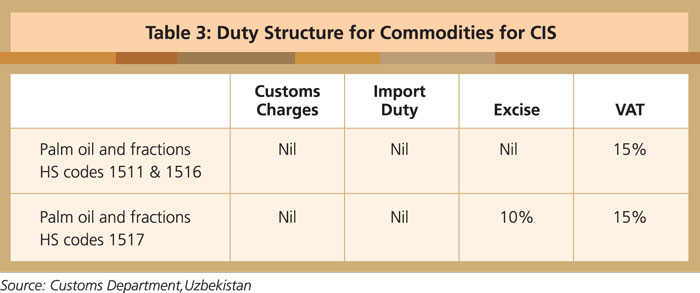

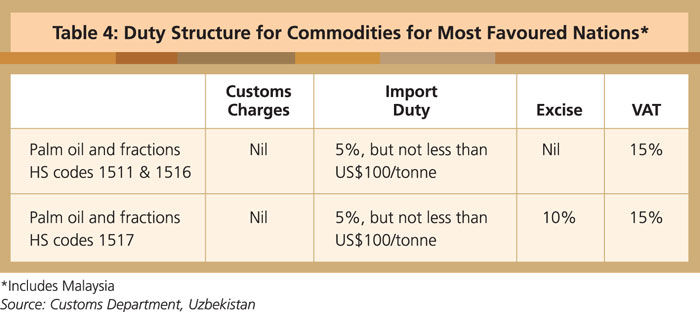

The import of palm oil had been heavily taxed, and Malaysian suppliers had to compete with suppliers in the CIS region who enjoyed a lower tax rate. In 2019, as part of the reduction of import duties on essential items, the government removed the import duty of 5% on palm oil fractions under HS code 1516 (hydrogenated oils). This resulted in a spike in the import of palm oil from Malaysia, from 42,625 tonnes in 2018 to 74,667 tonnes in 2019, or by 75%.

But this attracted a negative campaign by the region’s anti-palm oil lobbies, which was also picked up by some in the Uzbekistan government. In January 2020, the government again revised the duty structure on the import of oils and fats. All fractions of palm oil are now subject to 5% duty plus other applicable taxes.

Malaysian palm oil imports from January to June this year dropped to 29,474 tonnes compared to 31,031 tonnes over the same period in 2019, or by 5%. This was primarily because of the Covid-19 lockdown in all major cities of Uzbekistan.

Investment prospects

Uzbekistan holds strong potential for Malaysian palm oil in the CAR. With a long-term investment approach, it could become a hub for Malaysian palm oil exports to the entire CAR and CIS.

The government has developed seven special FEZs, with a wide range of tax breaks for investors. The FEZs offer exemptions from taxes (income tax and VAT), customs duties and taxes for goods imported for production and manufacturing needs, for a period of three to 10 years, depending on the quantum of investments. The government is encouraging foreign companies to establish processing plants to take advantage of tax breaks.

Malaysian palm oil industry players should capitalise on the investment opportunities, particularly in the downstream sector. The food industry, the primary user of palm oil, has shown consistent growth. Further growth can be achieved in the home cooking oil segment, which is currently dominated by sunflower oil.

Faisal Iqbal,

Deputy Director,

Marketing & Market Development; and

MPOC Pakistan