‘EU Forced Labour Regulation Must Not Punish Progress’

By gofb-adm on Thursday, November 24th, 2022 in Comment No Comments

By gofb-adm on Thursday, November 24th, 2022 in Comment No Comments

The European Commission (EC) is preparing a new regulation to target products produced with links to forced labour. It will give the EU the power to introduce trade bans, cut off financing and apply other sanctions to those suspected of benefitting (even indirectly) from forced labour.

This is additional to current EU proposals – the Environmental Due Diligence rules published as part of the Deforestation Regulation; and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive.

The new regulation will be more aggressive and targeted at importing companies. It signals that they could face sanctions on labour or human rights related issues. However, it also strikes a fair balance between the need to eradicate forced and child labour – and the need to establish a fair legal framework that respects natural justice. Other EU institutions should support this position.

Companies and other stakeholders must have a channel for engagement before sanctions are applied: this is how real and substantive changes can be made. Taking an adversarial approach by treating the private sector as guilty by default, will not help. Practical solutions are needed; not grandstanding. The EC’s proposal broadly achieves this.

There is no perfect labour market, without risk of forced labour, either inside the EU or outside. The proposed regulation should therefore not be used as a trade barrier against exporting countries or targeted at commodities for political purposes.

The Malaysian palm oil sector recognises the need for continuous improvement, including identifying areas of potential weakness, and also enhancing monitoring and enforcement. The sector is cooperating with government entities, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), NGOs and others in this process. The EU should seek to become a cooperative partner in this process, and not produce a regulation that creates conflict instead of cooperation.

Key facts and data

Malaysian palm oil sector

In Malaysia millions of small farmers, and plantation employees work daily to collect, transport and process palm fruits. This has provided income, security and the hope of a brighter future for many in Malaysia, and elsewhere via remittances.

However, the sector is not perfect and we recognise this. Widespread claims of poor labour practices have been levelled by the US government and other parties. Some claims are grounded in facts; others are inaccurate. The labour situation in the sector is highly challenging; the palm oil supply chain is complex; unfortunately, at times, this has been open to exploitation by bad actors.

Migrant labour is a common feature of agricultural systems the world over. Whether in Europe, the US or in Malaysia, the need for labourers – who have economic and social needs – is a challenge for industries and governments.

Oil palm plantations in Malaysia are no different. They require a large labour force, due to the high productivity and high production levels of the crop. As a small, rapidly developing country, Malaysia’s domestic labour force cannot meet these needs. Migrant labour is therefore an important element for plantation companies and – especially – for the 300,000 small farmers who require assistance to work their land.

Strong governance and compliance protocols

The Malaysian palm oil sector is governed by a modern and strong regulatory framework:

Commitment to labour rights improvements

The Malaysian palm oil community understands that it must live up to global labour rights standards, if it is to continue to successfully serve customers in the Asia Pacific, India, Europe, US and Middle East, among other international markets.

This means that questions about labour rights raised by any government, must be considered as global questions. They resonate across the supply chain. The customers are global companies, with high labour rights standards that apply to all markets.

The Malaysian palm oil sector is determined to live up to this responsibility. It has in recent months instituted a series of commitments and action plans implemented by private growers and palm oil companies. These actions send a clear message to customers, governments and stakeholders that the private sector is committed to rectifying problems that exist.

Commitments implemented by the government and private sector:

The Charter affirms the commitment of members to respect labour rights, adopt responsible recruitment practices and provide good working and living conditions for workers. It commits all members to a binding set of commitments on labour rights, including:

The commitments in the Charter are based on several international guidelines and frameworks:

A key consideration must be whether issues are systemic, whether reforms are underway and ILO protocols are implemented, and whether national laws and industry policies include labour rights commitments. In Malaysia’s case, it is clear those commitments are in place.

Increasing standards and compliance protocols

The MPOCC has undertaken significant revisions to the MSPO standards; these were published at the beginning of 2022.

The standards revision process included a broader range of stakeholders than when the original standards were drafted. They included the Malaysian Trade Union Congress and the National Union of Plantation Workers. Their representation was vital to the process, and is in line with international norms on labour rights and representation, specifically a tripartite (government, union and employer) approach.

MSPO certification is mandatory for palm oil production in Malaysia. This is enforced via the criterion for organisations to be licensed under the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB), the national regulator. The revised MSPO requirements are designed to align with ILO norms on labour rights.

Importantly, the MSPO provides almost no exceptions for any participants in the supply chain, upstream or downstream. The only exception provided is for independent smallholders, i.e. those not part of an arrangement with a larger plantation company.

This is in line with the social and employment norms that are part of broader standards, such as Social Accountability standards.

Setting the record straight

Malaysia has been subject to misinformation on labour issues. It is important to correct these inaccuracies.

Multiple US government agencies have publicly released assessments, including criticism, of the labour situation related to Malaysia’s palm oil sector. These assessments are based on a variety of qualitative and quantitative sources. The sources themselves, and the data and evidence they present, deserve significant scrutiny.

Decisions are made based on these sources and their data, which affect millions of workers, as well as cost companies millions of dollars. The US government in general is transparent about much of its source material, which allows an independent assessment to be made.

The Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) has undertaken a close assessment of a number of the source materials cited by the US Department of Labour, US Department of State and the US Department of Homeland Security’s Customs & Border Protection.

This assessment of the materials reveals that much of the data provided by sources such as NGOs or petitioner organisations, are out-of-date (in some cases by almost 40 years) or are not applicable to the specific complexities of the Malaysian palm oil sector.

The US Department of Labour’s assessment of the palm oil sector relies on significantly outdated sources and datasets, and fails to take into account initiatives undertaken by the private sector in terms of preventative action.

The US State Department’s assessment similarly fails to acknowledge the work undertaken by the private sector to establish better practices and NGO collaboration, where government policies have not kept up to date with global benchmarks.

The presence of child labour in Malaysian oil palm plantations has been confirmed by the government; yet the incidence is relatively small, largely isolated to the states of Sabah and Sarawak. For the most part, it involves unpaid family members assisting parents and children in legal employment exposed to suboptimal conditions; there is no evidence of widespread or systematic or institutional forced labour of children.

The claims ignore two things:

Many of the claims against the industry regard unethical recruitment of workers – the industry has taken steps against this and is continuing to seek workable solutions.

There is a significant conflation of Indonesia and Malaysia in many of the source documents and data, which betrays a lack of understanding of the significant differences between the countries themselves, and their palm oil sectors.

Child labour appears to have greater weight than migrant labour. This is in line with both emotive campaign tactics and the priorities of government policies around the world in attempting to eradicate child labour (but does not align with the focus on Malaysia, where there is no evidence of widespread forced child labour).

There is reliance in several instances on reports by campaigning organisations that are explicitly opposed to palm oil cultivation in the region. Using such reports as source documentation is not serious public policy, given the pre-existing bias. This approach weakens the claim that actions taken are independent and evidence-based, and undermines the goal of rooting out forced labour.

It is apparent that many NGO reports used as ‘evidence’ in building a case against Malaysia are largely based on recycled claims or claims that are relevant to the palm oil industry across ASEAN, or different industry sectors in Malaysia.

Only 10 of the reports – spanning more than a decade – used informant interviews. The use of informants is common, but when reports are based on old claims and recycled information, the use of informants is not serious.

The bulk of the reports simply repeated claims from other sources. While this is not a suggestion that these non-primary reports are not credible, there are instances where reports that would be considered ‘high profile’ – such as those by Liberty Shared and EIA – are closer to advocacy documents rather than investigative or analytical documents.

MPOC

By gofb-adm on Sunday, May 1st, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Comment No Comments

The European Union (EU) has long been at the forefront of regulatory advancement and innovative policies on trade and sustainable development, as well as the formulation of rules of commerce that directly affect third countries. The sheer breadth and depth of EU regulation are not comparable with most other regulatory environments, and often lead the way for other countries to follow suit.

To date, much of its attention has been directed at the palm oil industry – be it the increasing regulation of process contaminants like 3-MCPD; the detailed limits on nutrition and health claims, as well as food labelling; or policies to protect forests and prevent deforestation.

The conditions of market access for palm oil to the EU have further been influenced by unfounded campaigns in some member-states. These have created negative sentiments about the use of palm oil in food products and as a feedstock for biofuels, and exerted pressure for strict legislative controls.

New regulatory and legislative initiatives are now pending in the context of the European Green Deal, which sets out efforts for the EU to become the world’s first climate-neutral continent. The Farm to Fork Strategy aims for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system, while the Fit for 55 package targets policies in relation to climate, energy, land use, transport and taxation to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030. These are all set to apply to palm oil as well.

There are two key reasons why the Malaysian palm oil industry should take heed of these developments, and work within this environment to protect its trade interests.

Firstly, the EU has become an incredibly important ‘laboratory’ for new policies and novel regulatory approaches. It may be argued that it develops these complex measures unilaterally, but there is little doubt that its initiatives eventually do have an impact on the global trade environment.

Secondly, Malaysia’s palm oil industry – and the many people depending on it for their livelihood – continue to rely strongly on exports to the lucrative EU market. From 2010 to 2020, the EU ranged between second and third ranking as a destination for Malaysian Palm Oil. In 2020, it represented Malaysia’s second-most valuable export market for palm oil and palm-based products, with a value of around RM11.27 billion (EUR 2.35 billion).

Even the anticipated decline in EU demand for palm oil used for biofuel production and for oil palm crop-based biofuel will not see the commodity being immediately replaced. It will certainly not be offset by demand in other major markets, such as India and China, which offer relatively little additional room for expansion of their palm oil imports from Malaysia.

In addition, competition from other palm oil producing countries, as well as other vegetable oil producers, will reduce the possibility of new markets being found. Therefore, if only from a purely commercial perspective, the EU remains an important export destination for Malaysian Palm Oil.

Legislation on supply chains

In the coming months, the EU is expected to unveil a proposal for a new legal instrument that looks poised to affect supply chains around the world. Given that it will apply along entire supply chains, the proposed legislation will not only affect direct trade between the EU and a third country, but all countries along the supply and value chains.

In December 2021, the European Commission (EC) presented its proposal for an EU Directive on Sustainable Corporate Governance. This is expected to put forth detailed due diligence obligations related to social (labour) and environmental standards in corporate supply chains, as well as obligations for corporate directors to integrate mandatory sustainability criteria into their decision-making processes.

Similarly, in the context of the legislative initiative on deforestation and forest degradation – to reduce the impact of products placed on the EU market – the EC intends to ‘promote the consumption of products from deforestation-free supply chains in the EU’.

These initiatives will have implications for economic operators around the world – implications that many businesses may not yet fully realise, assess or appreciate until the rules are in place.

The impact may not be felt until, for instance, a food processing company in India requests its Malaysian Palm Oil supplier to comply with detailed social and environmental obligations, so that the Indian company’s products can be purchased by a European business that is required to comply with the new due diligence obligations.

Should Malaysia’s palm oil exporters decide to ship crude palm oil to India, for example, in order to avoid certain EU regulations, the strategy will be short-lived if the processed products containing Malaysian Palm Oil are then exported from India to the EU.

The rules on increased supply chain due diligence will mean that products exported to the EU from anywhere in the world and containing Malaysian Palm Oil would still be required to fulfil a certain number of criteria related to social and environmental standards.

In the context of the EU’s initiative on deforestation and forest degradation, additional due diligence rules that aim at ensuring that no deforestation has occurred, can also be expected. Given the ‘score’ accorded to palm oil in the EU’s previous elaborate calculation of the indirect land use change risk, it is likely that similar rules will also apply to palm oil for uses other than biofuel production.

Circumventing such rules by exporting to other markets will not be a sustainable option, as third markets would need to align themselves to EU standards and regulations in order to preserve their own trade opportunities.

Staying ahead of the curve

As the examples of the imminent due diligence obligations indicate, EU rules often affect other regulatory environments. This may, in turn, cause other countries to consider similar rules to harmonise requirements and thereby facilitate trade.

In simple terms, Malaysia and its palm oil industry should closely monitor and ‘police’ the EU market and regulatory initiatives, so as to always remain abreast of developments vis-à-vis global regulation. This is a prerequisite to preserving market access opportunities in the EU, and defending Malaysia’s rights within the international trading system should the need arise.

This would allow economic operators in Malaysia to understand in which direction the world is moving in terms of regulation – and therefore assess, influence and/or align with the standards-setting process in the EU and, ultimately, globally.

Without such coordinated and constant engagement, Malaysia will not only progressively lose the important EU market, but also be unable to understand, adapt or influence such initiatives in the EU or elsewhere. If anything, keeping up with developments in the EU would allow Malaysia to anticipate commercial and regulatory trends, and thereby remain competitive and attractive.

Merely directing its palm oil exports to other destinations may provisionally and partly compensate for losing the EU market, but will not fully relieve the Malaysian industry from complying with certain EU rules.

Therefore, Malaysia should not give up on the EU market, but rather increase its engagement in a way that allows European stakeholders to better understand Malaysia’s commitments to social and environmental standards. Such involvement will also allow Malaysia to contribute to the shaping of fairer EU rules.

Malaysia and its palm oil industry already have a long history of sophisticated engagement with EU regulators through the efforts of government agencies and industry stakeholders. Such efforts should continue and be even better coordinated and deployed.

Wan Aishah Wan Hamid

CEO, MPOC

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Comment No Comments

The European Union (EU), under its commitment to transparency, has improved avenues for stakeholders – both citizens and foreigners – to participate in its legislative and policy-making processes.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Comment No Comments

On July 16, 2021, the European Commission (EC) adopted its Communication on the New EU Forest Strategy (Forest Strategy) for 2030. The initiative is linked to the European Green Deal and builds on the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030.

The Forest Strategy recognises the central role of forests and the contribution of foresters and the entire forest-based value chain for achieving a sustainable and climate neutral economy by 2050. It reconfirms the EC’s commitment to forest management and deforestation-free supply chains, as set out in its 2019 Communication on Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests.

In the Biodiversity Strategy, which is the EU’s ‘comprehensive, ambitious and long-term plan to protect nature and reverse the degradation of ecosystems’, the EC notes that biodiversity loss and climate change require urgent action. On this basis, the EC set out to work on the Forest Strategy.

The Forest Strategy is also linked to the European Green Deal, which is characterised as a ‘growth strategy to transform the EU into a fairer and more prosperous society, with a modern, competitive, climate neutral and circular economy’.

Earlier in 2021, the EC held a public consultation on the Forest Strategy which, according to the relevant Roadmap, will focus on setting a policy framework to address ‘effective afforestation, forest preservation and restoration in Europe’.

While the Forest Strategy does not specifically refer to any implications for third countries, it makes reference to the EC’s Communication on Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests. This states: ‘EU consumption of food and feed products is among the main drivers of environmental impacts, creating high pressure on forests in non-EU countries and accelerating deforestation. Therefore, the consumption of products from deforestation-free supply chains in the EU should be encouraged both via regulatory and non-regulatory measures as appropriate.’

The core objective of the Forest Strategy is to help the EU to achieve:

The Forest Strategy recognises the central role of forests and the contribution of the forest-based value chain in achieving a sustainable and climate neutral economy by 2050. It sets out a policy framework aimed at delivering growing, healthy, diverse and resilient EU forests, which is intended to contribute significantly to the biodiversity ambition; secure livelihoods in rural areas and beyond; and support a sustainable forest bio-economy that relies on most sustainable forest management practices.

According to the Forest Strategy, forest management practices will be built ‘on a recognised and internationally agreed dynamic sustainable forest management concept that takes into account the multi-functionality, the variety of forests and the three inter-dependent pillars of sustainability’. Additionally, its annex provides for a Roadmap of action to plant 3 billion trees by 2030 in the EU.

Upcoming EU legislation

While the Forest Strategy focuses on EU forests, it reaffirms the EC’s commitment – made in its Communication to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests – to adopt legislation aimed at minimising the EU’s contribution to deforestation and forest degradation worldwide; and to promote the consumption of products from deforestation-free supply chains in the EU.

In 2020, the EC had published its Inception Impact Assessment for a legislative initiative on deforestation and forest degradation, and interested stakeholders provided initial feedback. A more detailed public consultation was held at the end of 2020.

The legislative proposal was published on Nov 17, 2021. Already in its Inception Impact Assessment, the EC had stated that one objective of the initiative is to promote the consumption of products from deforestation-free supply chains. The EC aims at introducing a due diligence system that would require businesses to ensure that their products, which are to be placed on the EU market, have not contributed to deforestation or forest degradation.

The legislative proposal on deforestation and forest degradation categorises countries as having a low, standard or high risk of deforestation and forest degradation. The categorisation will determine the respective due diligence obligations for companies selling products in the EU that originate in those countries.

In general terms, ‘simplified due diligence duties’ will apply to low-risk countries, while ‘enhanced scrutiny’ will be required for high-risk countries. However, the specific criteria for the classification remain unclear. In its proposal, the EC is limiting the scope of the requirements to six commodities – cattle, cocoa, coffee, oil palm, soybean and wood.

Public debate rarely makes a difference between sustainable and unsustainable palm oil production. More importantly, the oil palm is by far not the only agricultural commodity that should be considered in terms of the global environmental footprint – soybean, rapeseed, sunflower, canola, maize, sugar, beef and dairy production are arguably worse offenders and only some of those are covered by the EU’s proposal.

A report by the World Resources Institute states that deforestation on land used for oil palm cultivation has been decreasing since 2000; and that land use for cocoa and coffee has increased, while there has almost been no change for cattle farming.

As the EC itself has acknowledged, ‘deforestation and forest degradation are driven by many different factors’. This includes increased demand for food from a growing global population, feed, bioenergy and other commodities, ‘combined with low productivity and low resource efficiency’.

Partnership with producer countries?

Oil palm cultivation and its supply chain activities are extremely important for the economic and social well-being of Malaysia. The government remains committed to preserving its rich tropical forest coverage, as well as to sustainable cultivation of oil palm and the production of palm oil.

In 2019, the government capped the expansion of the oil palm cultivated area at 6.5 million ha, which effectively corresponds to a ban on new planting. Currently, the planted area covers 5.9 million ha. In addition, steps have been taken to ensure the sustainability of the oil palm sector, including implementation of mandatory certification for cultivators and palm oil producers under the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil standard.

At the same time, Malaysia has been stepping up action to protect forests and peatlands by further improving related laws and enforcement. Today, its forested area is estimated at almost 53% of the land area.

The New EU Forestry Strategy reaffirms the EC’s commitment to work ‘in close partnership with its global partners on forest protection, restoration and sustainable forest management’.

This commitment is also part of the Communication on Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests. In line with its development-cooperation principles, the EU intends to work in partnership with producer countries to fight deforestation and forest degradation.

It appears that the EU intends to achieve true partnerships with third countries, without any unilateral imposition of specific actions or measures, particularly those that do not appear to be scientifically justified, and which are proportionate and the least trade restrictive.

However, this is clearly not the case when it comes to biofuel feedstocks, where the EU has developed a trade-restrictive approach on indirect land use change. It also does not appear to be the case with the forthcoming legislative proposal on deforestation-free supply chains and related due diligence obligations.

Deforestation is a global issue that requires cooperation and multilateral solutions. More can be achieved through bilateral, plurilateral and/or multilateral cooperation than unilateral action, even if it is masked as ‘work in partnership’.

Malaysia’s commitment towards sustainability and forest conservation must be recognised and factored in when trade-related policies are defined and actions are taken by the EU. There needs to be effective partnership with Malaysia to define and adopt bilateral, plurilateral or multilateral standards and solutions for sustainable forestry and agricultural production compliance.

Malaysia and its palm oil industry should also be prepared to take a stand on the EU legislative proposal on deforestation and forest degradation. Engaging with the EU to define the scheme and conformity assessment procedures to certify Malaysia’s palm oil products as ‘deforestation-free’ would deliver comparative advantages vis-à-vis competitors, as well as eradicate the unfortunate image that the sector has endured in Europe.

The objective will require strategic thinking and planning; technical, commercial, scientific and diplomatic advocacy; and the commitment of human and financial resources on Malaysia’s part. It will also require the EU to truly engage in bilateral or multilateral negotiations.

The hope is that reason will prevail and that negotiated solutions can replace unilateral measures, trade irritants, dispute settlement proceedings and ineffective or partial solutions to the urgent problems of climate change mitigation, environmental protection and sustainability.

FratiniVergano

European Lawyers

By gofb-adm on Wednesday, September 29th, 2021 in Issue 3 - 2021, Comment No Comments

The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) urges the European Union (EU) to revise its approach on vegetable oils in biofuels under the framework of the revised Renewable Energy Directive; as well as the European Commission’s (EC’s) approaching deadline for adopting rules on certifying low indirect land-use change (ILUC)-risk biofuels and updating the list of high ILUC-risk feedstocks.

The CPOPC reiterates its opposition to the criteria laid down in a Delegated Act from March 2019, where palm oil is the only crop yielding a high ILUC-risk and is thus subjected to a freeze and phase-out from the EU’s renewable energy programme.

The use of ILUC as a policy tool has been fraught with methodological problems and biases from the beginning. Therefore, a new approach, which treats all sustainable vegetable oils equally – based on verified production practices and not on the type of commodity – is urgently needed. After all, commodities in themselves are not responsible for deforestation – it is the practices that matter.

Palm oil was singled out as ‘damaging to the environment’ based on a comparison study that used 2008-16 as a gauge for ILUC. This timeline discriminates against countries that were late in development as their growth during that period affected the most Land Use Change (LUC).

The CPOPC argues that a proper timeline to determine the sustainability of vegetable oils for renewable energy should be 1960-2016. This provides an equitable comparison where the dynamic contribution of palm oil to the sustainable development of Indonesia and Malaysia in post-colonial times can be highlighted against global LUC.

This further allows the consideration of new data on LUC which was not available to the EC at the time of its consideration of ILUC. A study by Nature tracked LUC from 1960-2019 and identified 43 million sq km from the Global North to the South. Estimates on palm oil cultivation globally put it at a mere 250,000 sq km.

The global ambition to decarbonise is one of supreme urgency. The recent decision by G7 countries to back off ambitions for electric vehicles is a clear signal that biofuels are a needed tool in fighting climate change without disrupting global economies.

The EU’s bias against palm oil threatens its own ability to decarbonise its transport and energy sectors. Clear evidence of its bias can be seen in its analysis of Annual Net Increase of Harvested Area 2008-16, which highlighted palm oil as the highest at 4%. This puts palm oil at the highest risk of ILUC if one only looks at the percentage.

It must be noted that the same analysis showed considerably larger land footprints of other vegetable oils. Palm oil started at a base point of 15.369 kha, while rapeseed and soybean started at 30.093 kha and 96.380 kha respectively. The EU analysis granted rapeseed an annual net increase of 1%.

This is a clear distortion of facts. Had palm oil producing countries developed at the same pace as rapeseed producing countries, palm oil would have shown a 2% increase instead of 4%. The most apparent distortion of facts is in granting soybean 3% based on a start point and an annual increase of harvested area that is more than four times larger than oil palm.

Seen in this perspective, the CPOPC argues further that the energy yield per hectare of land used for biofuels must be properly included for fair analysis. Scientific research has shown that palm oil has an energy efficiency that is four times that of rapeseed or soybean. Once this knowledge is applied to the EU analysis on land use of vegetable oils, it would place oil palm as the most efficient crop for renewable energy.

In addition to land use, recent studies on the environmental impacts of tilling and heavy agri-chemical use for soybean and rapeseed demand that the EU includes the environmental impacts of these vegetable oils as their contribution to climate change, as this is more quantifiable than the ILUC supposition.

Confidence in producer countries

The major palm oil producing countries of Indonesia and Malaysia, both of which have interests in the EU’s biofuels programme, have shown commitment and concrete actions as to the sustainability of their production.

The Indonesian moratorium on new licenses for oil palm and Malaysia’s commitment to cap the cultivated area are just two examples of sustainable land use management. The significant decrease of wildfires and deforestation in Indonesia provide firm evidence of its commitment towards sustainable vegetable oil production.

CPOPC credits the two countries for this phenomenon, as both strive towards sustainable management of their natural resources, and the positive impact of oil palm in lifting millions of farmers out of poverty.

The implementation of national certification schemes in the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) and Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) has also been instrumental in quantifying the sustainability of production.

The CPOPC acknowledges the EU’s concerns on the efficiency of voluntary certification schemes and looks forward to proving the efficiency of mandatory national schemes in removing deforestation from EU imports.

The ISPO and MSPO are without peer in the global production of vegetable oils. The CPOPC believes that these twin certification schemes provide the right path towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for both the EU and palm oil producing countries; ultimately, this can be a global model for sustainable vegetable oils.

Palm oil producing countries look forward to the EU-ASEAN Joint Working Group on sustainable vegetable oils where a holistic and non-discriminatory approach towards vegetable oils can be developed to meet the SDGs.

CPOPC

This is a slightly edited version of an opinion piece posted on June 23, 2021 at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/opinion/cpopc-calls-on-eu-to-adopt-non-discriminatory-biofuels-policy-to-fight-climate-change/

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Comment No Comments

Malaysia will review the European Union’s (EU’s) reasoning in phasing out palm-based biofuels under the Delegated Act of the revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED II).

Plantation Industries and Commodities Minister, the Hon. Dato’ Dr Mohd Khairuddin Aman Razali, said a Malaysian government delegation had held consultations with EU representatives on March 17, via the Dispute Settlement Mechanism of the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Malaysia had filed a complaint before the WTO, according to a Ministry statement issued on Jan 15.

The country is seeking a fair judgment over the EU’s action, which will exclude palm oil as part of the EU’s biofuels mix by the end of 2030. Malaysia also wants the EU to redefine its interpretation of oil palm cultivation, which the latter has classified as ‘high-risk’.

The consultation process is among efforts to arrive at a solution over the EU’s action, which Malaysia deems to be discriminatory, the Minister said in a statement.

“Malaysia will review the feedback and clarification provided by the EU throughout the consultations. Further action will be taken accordingly, guided by the rules and procedures that have been outlined by the WTO.”

Malaysia’s representatives at the consultations comprised officials of the Attorney-General’s Chambers, International Trade and Industry Ministry, Foreign Affairs Ministry, and Water, Land and Natural Resources Ministry.

Indonesia and Colombia acted as observing countries, with both being members of the Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries.

Under RED II, the EU is moving to raise the share of renewable sources in the energy consumption mix to 32% of the total energy consumption, while phasing out the inclusion of palm-based biofuels by 2030.

The EU has claimed that oil palm cultivation contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation and indirect land-use change, and is therefore a ‘high-risk’ activity.

Indonesia’s complaint

Indonesia, the world’s biggest producer of palm oil, had filed a complaint before the WTO in December 2019, on the basis that the EU’s restrictions on palm-based biofuels are unfair.

Malaysia is a third-party observer in the case, along with countries such as Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Thailand, Australia, Brazil, the US, Costa Rica and India.

China, Canada, Singapore, Turkey, Norway, Russia, Argentina and Japan are also taking an interest in the matter.

The consultations held on Feb 19 last year had failed to settle the dispute, leading to the establishment of a panel to adjudicate the issues.

Indonesia and Malaysia are the world’s top producers of palm oil, supplying about 85% of the output.

Source: The Malaysian Reserve.com

March 19. 2021

This is an edited version of the report.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Comment No Comments

As countries roll out Covid-19 vaccines and economic reopening strategies, another crisis lurks: climate change. How governments approach economic recovery will determine how fast they bounce back from the pitfalls of 2020. Yet, it will also be a crucial indicator of how they will fare in the face of future crises. While some countries are using this as an opportunity to ‘build back better’, developing nations are struggling to keep up – a situation which will leave the world vulnerable to disaster.

Covid-19 has severely impacted our economies. Industrial nations of the North are encountering recessions greater than the 2009 financial crisis – for instance, the UK’s economy fell 9.9%, double what occurred in 2009 – and poorer countries of the South are predicted to lose a decade of development. But scientists are already looking beyond the impending recession to calculate the next calamity. If the world does not address climate change and rising carbon emissions by developing a new ecological approach, rebuilding successful economies in a post-Covid world will be fruitless.

For the foreseeable future we need to stimulate the receding economy while prioritising the environment. A new paper published in the peer-reviewed Global Policy Journal (GPJ) believes this can be accomplished through new trade deals and ecological pacts – crucially, a North-South ‘Green Deal’, a global environmental coalition led by the EU, which would encourage sustainable production and boost economic trade.

The UN has already encouraged all governments to view post-Covid recovery as a chance to integrate sustainability practices into economic models, overturning pre-Covid systems and building post-Covid solutions which support net-zero pledges and the Paris Agreement.

Disappointingly, the latest UN report revealed that only 18% of the US$1.9 trillion allocated for recovery from Covid-19 can be considered ‘green’. While disappointing, it is not unsurprising, given that the enduring economic model does not reward environmental collaboration or accountability. Indeed, it leaves too much room for narrow-minded solutions and paves the way for deadly mistakes.

Global coalition

Even with the lessons of Covid-19, the world keeps forgetting we are intrinsically connected. If the North succeeds in implementing its versions of the Green Deal – switching to clean industrial innovation while curbing carbon emissions – the planet will still be vulnerable as the South is forced to rely on fossil fuels and deforestation to attain economic stability. If Northern trade blocs, like the EU, truly hope to transition to a post-carbon future and meet Green Deal promises, they must realise this cannot be achieved in isolation.

This would mean reimagining the current approach. The EU has notoriously overlooked partnership opportunities with producer nations. For example, in an attempt to combat imported deforestation, the EU has banned the import of palm oil as a biofuel from 2030. However, this de facto ban has unintended consequences and, as stated in the GPJ, created a trust deficit between the EU and Asia – which believes the EU is ignoring science in lieu of its protectionist tendencies.

The oil palm, which is an incredibly efficient crop, is able to produce more oil per hectare of land than the EU’s replacements of soybean, rapeseed, coconut and sunflower. Importantly, Europe’s ban does not stop producer nations from cultivating oil palm. It is believed this ban will only force these nations to sell palm oil to China and India – meaning there will be less pressure for palm oil to meet sustainable standards. Ultimately, the EU’s boycott will cause displaced deforestation and diminish efforts in producer nations to meet sustainable goals.

What the EU seems to be overlooking is that trade is an important tool in achieving environmental protection and economic growth. Trade can be a catalyst; a prime example is a recent UK Environment Bill which reveals supply chains and curbs deforestation by forcing UK businesses to import commodities which abide by the environmental laws of producer nations. This obliges UK businesses to collaborate with manufacturers, and incentivises policies which encourage sustainable production.

If the EU can do something comparable, then they can enter a coordinated, global Green Deal which prioritises sustainable economies and guarantees prosperity for humanity and the planet. If the EU adopts this mindset, it could partner with existing mandatory regulations, like the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil certification scheme, which if guided by the EU could be better enforced and implemented.

We need a new economic approach which emphasises the environment – a global pact which values mutually beneficial relationships, and encourages the world’s finest sustainability practices across energy, agriculture, transport and health. Importantly, we must address the root causes of pandemics and economic inequality.

Global coalitions can transform national, narrow Green Deal promises into global systems of sustainable advancement and prosperity; new models which offer protection from novel diseases, impending recessions and destructive climate change – the emergencies of tomorrow.

Professor Ibrahim Ozdemir

Ecologist

Source: The CSPO.org, March 23, 2021

This is a slightly edited version of the article, which is available at:

https://commentcentral.co.uk/north-south-green-deal-best-antidote-to-looming-recession/

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Comment No Comments

A new World Wildlife Fund report, released around the same time as a sharp acceleration in Amazon deforestation, concludes that the rampant destruction of nature led to the Covid-19 pandemic – a view reinforced by the UN and WHO.

It also warns that future deforestation could unleash new global crises – from climate change to pandemics and biodiversity collapse.

That is why putting an end to deforestation once and for all must now be an urgent priority. The evidence confirms that relentless industrial expansion is consistently breaching the planetary boundaries necessary to maintain what scientists call a ‘safe operating space’ for humanity.

Thankfully, the EU’s trade balance gives it some leverage to tackle deforestation in a post-Covid world reeling from economic turmoil.

But merely boycotting problematic commodities implicated in deforestation won’t work – and often leads to the exports of those same commodities being redirected to regions with far lower environmental standards.

Indeed, the European Union (EU) has quietly conceded that its previous approach to stopping deforestation due to palm oil is unlikely to work.

A paper published by the European Parliament’s Directorate General for External Policies of the Union cites recent scientific studies on ‘deforestation linked to palm-oil production’ showing that solely reducing Europe’s own imports of palm oil is environmentally ineffective.

Instead, the paper concludes that ‘it is more effective and less costly if Malaysia and Indonesia’ – the world’s largest palm oil producers – ‘implement a moratorium on deforestation (targeting deforested areas)’.

This is because a palm oil boycott tends to simply switch demand to less efficient vegetable oils which use up more land, potentially driving greater rates of deforestation. It also signals to producer countries that adopting sustainable production methods is pointless because Europe doesn’t want to buy their palm oil anyway.

The question, of course, is how to incentivise developing nations to implement verifiable and effective forest conversation policies. A recent call in a report by the EU’s Agricultural Committee for new inclusive trade partnerships with the Global South attempts to address this issue.

The Committee warns that only mandatory, legally enforceable environmental standards can stop deforestation. But it also notes that such standards cannot be imposed unilaterally, and require buy-in from producer nations.

‘Stick and carrot’ approach

The big question missing from the EU’s ruminations so far is how to achieve this buy-in. There is one way: Working in partnership with the global south will mean adopting an aggressive ‘stick and carrot’ approach to trade deals.

Nations that meet environmental standards can be put on track for Free Trade Agreements. Those that refuse to do so would fall outside the negotiating table. That would be a huge step in spurring a global green economic revolution.

In Malaysia, there is now ample precedent for this process. The Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) standard is [a] national, government-mandated palm oil certification scheme enforceable by law.

Unlike voluntary schemes, like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil – catering for big corporate producers – the scheme is obligatory for all palm oil producers, more accessible to smallholder farmers, and enforced with fines for those who refuse to comply.

Unfortunately, the EU is still playing catch-up. The Directorate General report cites outdated research from last year to claim that in Malaysia and Indonesia, ‘attempts to limit palm oil-driven deforestation… fall short of their stated goals: less than one-third of palm oil production is certified, and often, certified areas overlap’.

But this is untrue. Since [the decision to make] the MSPO scheme mandatory, [ 71.1%] of oil palm plantations became certified as at the end of 2019. And Malaysia is aiming to certify 100% of its palm oil by the end of this year.

Further new research suggests that, in contrast to the Amazon where deforestation is accelerating, the MSPO scheme is working.

The World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch this month released new data showing that for three consecutive years, Malaysia’s rate of deforestation has slowed down – a development attributed to local ‘efforts to reduce deforestation’.

All this points to an unfortunate gap between EU perceptions and facts-on-the-ground, suggesting that the EU had rushed through its well-intended deforestation policies too haphazardly, without attention to key facts, and lacking sufficient engagement with countries who appear to be making real progress.

To be sure, we must not be sanguine. Rates of deforestation remain out of control, and if we do not act now, the Covid-19 crisis teaches us that human civilisation itself is in peril.

But the MSPO is one scheme showing that there is a path forward, one that might be scaled to other regions facing the scourge of deforestation. That is all the more reason the EU should find ways to work more closely with developing nations to support, rather than alienate, nationally-mandated conservation efforts.

This could help usher in a new global cooperative architecture that can cultivate trade in sustainable goods and services while using the full force of law to put an end to deforestation once and for all.

That may well avert the next global crisis.

Fazlun Khalid

Founder,

Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Sciences,

Birmingham, England

This is a slightly edited version of the article posted on July 10, 2020, at:

https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/opinion/eus-trade-deals-can-put-an-end-to-deforestation/

By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Comment No Comments

As someone who has worked for the palm oil industry during exciting and challenging times, I must say it remains a dynamic one. However, it has continued to attract global attention for the wrong reasons.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Saturday, October 3rd, 2020 in Issue 3 - 2020, Comment No Comments

As countries across the globe continue to grapple with the impact of the pandemic, and struggle to meet their economic and social obligations, the UK government has proposed a new law that will put further pressure on businesses.

New requirements recently announced in the UK could increase the cost of doing business, at a time when most economies are still trying to get COVID-19 under control, and putting in place measures to address the economic damage to many sectors and businesses.

The UK government, on 25th August, announced plans to introduce a new law to ensure that the supply chains of companies, and the products they sell, are free from illegal deforestation.

This is to ensure that consumer countries allow only legal commodities into their markets.

The proposal would prohibit larger businesses operating in the UK from using products grown on land that was deforested illegally.

This means companies will be responsible to ensure that their products were produced in line with local laws protecting forests and other natural ecosystems, as outlined by the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA).

To achieve this, businesses would be required to carry out due diligence on their supply chains, and publish information to show where the key commodities – such as cocoa, rubber, soy and palm oil – came from, and that they were produced in line with these local laws.

Seven key commodities have been identified under the proposal – beef and leather, cocoa, palm oil, pulp and paper, rubber, soya and timber.

Businesses that fail to comply would face fines, with the amount to be determined later.

The UK government has begun a 6-week online consultation to seek views from stakeholders on whether it should introduce the new law.

According to DEFRA the proposed law would:

Larger businesses will be targeted, as they are considered to be influential, and able to send a positive signal to producers.

Elena Polisano, forests campaigner at Greenpeace UK, said: “DEFRA’s proposal to make it ‘illegal for larger businesses to use products unless they comply with local laws to protect natural areas’ is seriously flawed.

“We will never solve this problem without tackling demand. Companies like Tesco, which sells more meat and dairy, and so use more soya for animal feed than any other UK retailer, know what they need to do to reduce the impact they are having on deforestation in the Amazon and other crucial forests”. (Ecologist, 25 August 2020)

“They must reduce the amount of meat and dairy they sell, and drop forest destroyers from their supply chains immediately.”

The new proposed law comes after the Global Resource Initiative (GRI) – the Government’s independent taskforce – was set up last year to see how the UK could ‘green’ international supply chains and reduce the footprint on the global environment by slowing the loss of forests.

The taskforce’s report stated that supply chain transformations were required for the UK’s own imports and consumption of seven key commodities – beef and leather, cocoa, palm oil, pulp and paper, rubber, soya and timber.

It called on the UK to take urgent action to ensure that the production, trade and consumption of agricultural and forestry products have a positive impact on people and the planet by:

Sir Ian Cheshire, chair of the independent taskforce, said that every day, British consumers buy food and other products which contribute to the loss of the world’s most precious forests.

He said the UK needs to find ways of reducing this impact if the country wants to tackle climate change, reduce the risks of pandemics, and protect the livelihoods of some of the world’s poorest people. (The Grocer, 25 Aug 2020)

In the past, similar measures were seen in the timber sector, under the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Action Plan, the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR), which came into effect in March 2013. The EUTR prohibits illegal timber and paper products from entering the European market, also via a due diligence system.

EU plans to introduce mandatory supply chain due diligence

As part of the European Commission’s (EC) 2021 work plan and the European Green Deal, the EU plans to also introduce legislation on mandatory supply chain due diligence for EU companies – as announced by the European Commissioner for Justice, Didier Reynders . This is to ensure that sustainability is embedded into the corporate governance framework.

This announcement followed a study commissioned by the EC, examining due diligence requirements through the supply chain.

The study concluded that the introduction of mandatory due diligence requirements would yield the greatest positive impact. A key finding of the study was that any new law should be cross-sectoral and applicable to all businesses, regardless of size.

The mandatory due diligence requirement would involve a legal mechanism, which imposes a “legal standard of care”. This means the due diligence carried out by a business should be objectively

sufficient in order to discharge its duty.

In other words, the proposal is “outcome-based”, rather than a procedural approach. No liability would be imposed if the business can show it undertook reasonable due diligence.

This development will require businesses to reinforce their compliance programmes and apply greater focus on these areas, including in the context of supply chain and other business relationships, and M&A and financing arrangements. (EC Study on due diligence requirements through the supply chain).

To mitigate reputational risks and meet the higher standards requested by consumers and investors, businesses have been taking their own initiatives to prevent or minimise their human rights or environmental impact by conducting training, having contractual clauses, codes of conduct and/or audits.

Even though companies have been voluntarily reporting requirements on due diligence, there is a push for a legal landscape as opposed to corporate reporting, owing to concerns over the quality of these due diligence processes.

Corporate reporting is considered insufficient to gauge actual practices carried out by the companies, as there are claims that these could be merely reactive responses to external pressure from NGOs or media campaigns.

While audits and certification schemes are common in commodity sectors, there are concerns that this approach could be limited, as it may not address the actual identified risks and actions taken to mitigate.

Audit and certification schemes usually only provide information about whether a supplier ‘passed’ or ‘failed’ an audit against a defined standard, rather than shedding light on what risks were identified, and how these can be mitigated.

These schemes also focus on what has happened during the past year, rather than considering what could happen in the future, and how emerging risks can be addressed.

An approach that focuses on the future – rather than past – is considered to be far better in mitigating risks.

The certification approach has been used for many agricultural products, but there are claims that it fails to deal adequately with the sector’s environmental and social problems.

There is now growing interest in parts of the agricultural sector, to look at how to better link the certification of products with legislative proposals.

Other challenges include the cost of certification, which often disproportionately falls on smaller businesses and producers, such as small farmers.

Although there are certification schemes in place, such as the RSPO, ISCC, MSPO, and ISPO in the palm oil sector, NGOs have been pushing for more stringent rules as they consider the schemes to have not adequately addressed environmental and social problems.

The stringent requirements often touted by NGOs would eventually increase the cost of doing business, making it difficult for commodities to compete in the global market.

Frustration is mounting amongst commodity producers, as rules are being selectively imposed to protect local producers from competition.

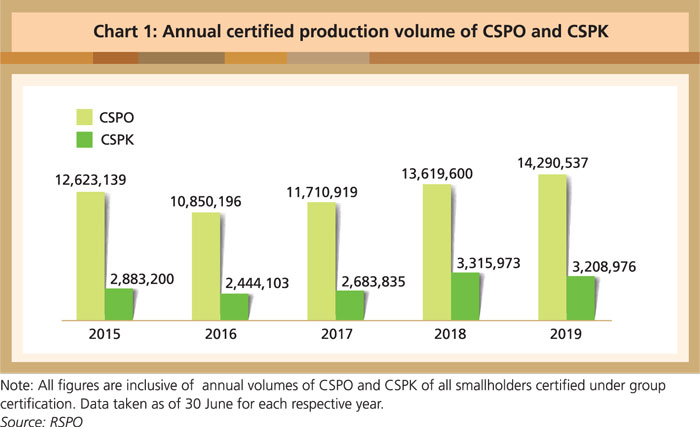

In addition, not all certified sustainable palm oil has found a market. Although there has been a healthy growth in production of certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) demand remains lukewarm.

Due to the supply and demand imbalanced, only 50% of CSPO oil is taken up. Ultimately, it makes no business sense to keep increasing production costs, due to new requirements, if this is not met with sufficient market demand.

Although it is in the interest of the commodity sector to meet market expectations, this must be compensated with sufficient profits for the time, effort and costs incurred to ensure supply chains are certified sustainable.

All sectors understand the need to sell high quality products that meet consumer demand, but only with sufficient profits, funds can be ploughed back into the business, and practices can be further improved. This is in the interest of producers, buyers, as well as consumers.

One could argue that the proposed new law is meant to ensure that companies step up their efforts to buy CSPO oil, or end up paying a heavy penalty.

However, why should, for example, palm oil producers face such scrutiny when they have kept their side of the bargain by adhering to certification requirements? It is the buyers who have not kept to their promise.

The new rules emerging from either the EU or the UK sends a strong signal to producers that Europe will continue to impose new barriers to the export of palm oil.

Sustainability clauses will likely become a norm in trade negotiations.

The EU is emerging as a global rule maker and sustainability standard setter. The rules set by the EU will eventually also be practiced globally, and will have an impact on palm oil producing countries. Once these rules or standards are endorsed, they will become global standards.

In this instance, it also looks like the UK and the EU are both competing to set global sustainability standards, which could disadvantage commodity-producing countries that have invested time and resources in ensuring that their supply chains are fully certified according to local laws.

If this continues, producer countries will lose interest in these markets as the cost of doing business increases. After all, cost remains a significant factor in any business, especially during the current challenging business environment.

Introducing a due diligence obligation puts the UK at the fore front for establishing legislation for products that they consider as a threat to forests.

But it also signals that both the UK and the EU are competing to be global trend setters for sustainability regulations.

It is imperative that Malaysia moves to ensure that the MSPO scheme meets these new requirements.

It is equally important that producers seek a long term assurance that local schemes, that have received support from small farmers, are recognised and supported.

With commodity producers going through a tough time, importing countries should find ways to strengthen local schemes to meet their requirements, rather than to keep re-inventing the wheel and adding further pressure and costs.

This is especially important for food commodity sectors, as they are essential for satisfying the increasing needs of consumers worldwide.

Belvinder Sron

Deputy CEO, MPOC