Future of Palm Oil: From Confrontation to Collaboration?

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019 in Issue 3 -2019, Special Report No Comments

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019 in Issue 3 -2019, Special Report No Comments

Sir Jonathan Porritt

Founder Director, Forum for the Future

The oil palm industry in Southeast Asia has found itself under constant pressure over the last 15 years from environmental and development non-governmental organisations (NGOs), based predominantly in Europe and the US. Opinions vary as to the effectiveness of that campaigning pressure, but few would deny that the industry has significantly transformed both its policies and its practices to reduce its environmental and social impacts on the ground. There is a clear case to be made that it has moved further and faster than other globally-traded commodities during the same period of time, and many question why those other industries have not been exposed to the same intensity of campaigning – on deforestation and land use issues, in particular.

Growers in Southeast Asia and elsewhere are angry and mystified; consumers in Europe and the US (largely ignorant as they are of the critically important contribution the oil palm industry makes to both GDP and the lives of millions of people in Southeast Asia) are confused and easily persuaded that adopting a ‘No palm oil’ position is the most ‘responsible’ way forward. Building on the revised Principles & Criteria from the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, the author will explore opportunities for reconciling some of today’s seemingly intractable confrontations.

This Keynote Lecture was presented at the 9th International Planters Conference of the Incorporated Society of Planters held in July in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Back in 2012, I was invited by Sime Darby Bhd to contribute to its Prestigious Lecture Series. I was honoured and intrigued, though more than a little ignorant about the oil palm industry at that time. It was certainly not my intention to spend the next seven years of my life becoming more preoccupied with this sector of the global economy than any other! I’m significantly less ignorant than I was, but still learning.

It has been an extraordinary privilege, and it remains a privilege to act as the Independent Sustainability Advisor to the Board of Sime Darby Plantation Bhd. My passion in life is sustainable development. Not the environment per se, but the interplay between the environment, the economy, society, individual responsibility, and what it is that allows all of us to make sense of our brief span of time on this beautiful planet of ours.

When the Brundtland Report – ‘Our Common Future’ (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987) – came out, I had already been actively involved for more than a decade in advocating for more sustainable ways of creating wealth. But the definition of sustainable development that it advanced at the time (‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’) has provided a useful hook ever since. Not least because it obliges all of us to think about what is known as ‘intergenerational justice’ – what is it that one generation owes all those generations to come, in terms of the legacy we leave them?

And the oil palm industry is undoubtedly one of those sectors where the practice of sustainable development (rather than the theory) has had to be pioneered and worked through in enormous detail. In September 2015, the UN General Assembly signed off on a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to be delivered by 2030. Of the 17 Goals, 10 are directly relevant to the industry:

| Goal 1: | End poverty in all its forms everywhere. |

| Goal 2: | End hunger, achieve food security and improve nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture. |

| Goal 3: | Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. |

| Goal 8: | Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all. |

| Goal 9: | Build resilient infrastructure, promote sustainable industrialisation, and foster innovation. |

| Goal 10: | Reduce inequality within and among countries. |

| Goal 12: | Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. |

| Goal 13: | Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. |

| Goal 15: | Sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, halt biodiversity loss. |

| Goal 17: | Revitalise partnerships for sustainable development. |

Embracing the SDGs means taking an integrated view, seeking to optimise outcomes across all the goals rather than cherry-picking any one particular goal at the expense of others – a point to which I will return later.

It’s also true to say that no other large-scale agricultural commodity has had to take such full account of its impacts (economic, social and environmental), or to improve its overall performance so significantly in order to meet the demands of its principal customers around the world. Many involved in the industry itself see this as disproportionate scrutiny, and often ask why it is that many of their competitors (other vegetable oils, and particularly the soybean industry) merit so much less attention. On the other hand, campaigners see the focus on the industry as entirely appropriate, given the level of tropical deforestation (impacting both on climate change and concerns about biodiversity) for which it has been held responsible historically – and, to a lesser degree, currently.

The last year has provided us with the most compelling evidence as to the importance of those campaigns. In October last year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its ‘Global Warming of 1.5ºC Report’, powerfully reminding governments that although the difference between an average temperature increase of no more than 1.5ºC by the end of the century, rather than 2ºC, may not sound particularly significant, the consequences of going to the higher rather than the lower figure will be very grave indeed – for the whole of humankind – in terms of the increase in extreme weather events, impacts on food production, rising sea levels and so on.

Since then, more detailed reports from both the Arctic and the Antarctic have revealed that the melting of the ice, at both ends of the world, is gathering pace at a rate that scientists find hard to believe. The implications for rising sea levels in this century are beyond grave.

And it’s been much the same story in terms of our gathering realisation of the damage we’ve done to the web of life on which we still entirely depend. In September last year, WWF International published its biennial Living Planet Report, with the still shocking headline that 60% of the populations of all vertebrates have been lost since 1970.

Further reports have highlighted impacts on other species, perhaps most disturbingly on populations of insects all around the world. A major study in February – ‘Worldwide Decline of the Entomofauna: A Review of its Drivers’ (Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys, 2019) – highlighted just how comprehensive and extensive the damage has been over the last 30 years, with 40% of all insect species now in rapid decline. Without insects, food webs collapse and ecosystem services fail, threatening the existence of all other species. Understandably, some have described this as ‘an insect apocalypse’.

There will be few industries more aware of the importance of pollinating insects than this one, transformed as it was by the introduction from West Africa of the pollinating weevil, Elaeidobius kamerunicus, in 1981.

Accelerating climate change and devastating biodiversity loss are two sides of the same coin. And we have left it so late that we now find ourselves in an out-and-out emergency on both counts. Awareness of this is now growing, with the powerful advocacy of superstars like David Attenborough influencing more and more people. But levels of indifference or outright ignorance remain disturbingly high.

That is true, I’m afraid, even here in Malaysia. One of the unfortunate consequences of the oil palm industry finding itself under such concerted attack for its contribution to deforestation was a defensive instinct, along the way, to disparage the science of climate change. There are still significant pockets of ‘denialism’ within the industry, intent on arguing that climate change is predominantly a natural rather than a man-made phenomenon, or that it’s nothing like as serious as mainstream scientists now recognise it to be – almost unanimously. This has been deeply unhelpful in terms of enabling the industry to thrive indefinitely into the future without any further impacts on Malaysia’s forests or peatlands, and it would greatly enhance the reputation of the industry today were it to develop a definitive position of its own on both the science and the accelerating impacts of climate change.

I would argue that this body of scientific work has to be our starting-point in any debate about the future of the oil palm industry. It tells us that we have no more than 10-15 years to do what we need to do to avoid the threat of runaway climate change. And part of the answer to that emergency is to stop clearing any more mature forest – and, indeed, to plant as much new forest as can possibly be achieved.

But I am not an absolutist when it comes to interpreting what that means in practice. For instance, I do not believe that the language associated with ‘zero deforestation’ has been particularly helpful in terms of changing behaviour on the ground. As Co-Chair of the High Carbon Stock Science Study, generously supported by Sime Darby Plantation and by many companies represented here today, (which published its Final Report in December 2015), I was keen to help people understand the important difference between ‘zero deforestation’ and ‘zero net emissions’ from land use change – or ‘no net loss’.

The Report from the Study’s Technical Committee concluded:

‘Experience over the last 20 years has taught us that no amount of high-level declarations will protect forests on the ground unless and until local people and communities can see their own economic interests and historic entitlements are better met through forests being set aside and protected for the long term, rather than cut down for short-term gain.’ (Raison et al., 2015)

It must also be clear to everyone involved in this debate that the only way to protect the world’s remaining rainforests is for relevant nation states (or regional/provincial jurisdictions) to legislate for such an outcome. However good their intentions may be, voluntary ‘no deforestation’ commitments signed up to by progressive non-state actors, from both the private sector and civil society, will only ever have a limited impact.

Progress on the part of consumer goods companies in the West has been particularly disappointing. In May this year, a report from WWF and the Zoological Society of London revealed that almost one in five RSPO Members had failed to submit proper progress reports to the RSPO, including many consumer goods manufacturers and retailers.

In March, the Global Canopy’s ‘Forest 500’ Report assessed the progress of 350 leading companies against their commitments to ensure deforestation-free supply chains, made either through the Consumer Goods Forum or the New York Declaration on Forests: ‘The most powerful companies in forest-risk supply chains do not appear to be implementing the commitments they have set to meet global deforestation targets. With just one year left to the 2020 deadline, it is clearer than ever that even companies with strong commitments will not be able to assert that their supply chains are deforestation-free by that deadline.’

Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (CSPO) accounts for about 19% of global palm oil production, but no more than 50% of this volume is actually sold as CSPO. This continuing hypocrisy on the part of so many Western companies (in effect, continuing to put ‘cheap’ before ‘sustainable’) is, in my opinion, entirely reprehensible.

Without unambiguous legislative foundations, and a determination to enforce whatever regulations are put in place, it’s difficult to see how the oil palm industry will ever be free of the kind of controversies that have flared up so frequently over the last decade or so. That’s why the current positioning of the Malaysian Government is so critical.

There are, of course, longer-term threats to the future of the industry that no government will be able to do much about. Back in 2016, I visited a huge bio-refinery in Brazil, using that country’s abundant sugar cane as feedstock to fatten up genetically modified microorganisms to produce oils identical in every way to ‘natural’ vegetable oils – apart, that is, from their price! But how long will it be before biotechnologists manage to crack that problem of high costs as well?

And then there are all the risks associated with accelerating climate change, which are already having a marked impact on the industry, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Each company in the industry should be assessing its portfolio of landholdings to determine high-risk assets, developing mitigation strategies (through improved agronomy, more efficient irrigation and so on), and ensuring that it is not left with ‘stranded assets’ on its books.

There will be many other climate-induced changes. Within the next 15 years, the European car market will have been fundamentally transformed, with the internal combustion engine progressively ousted by hybrids and pureplay electric vehicles. Demand for diesel in Europe is already steadily declining, year on year, primarily on account of concerns about air pollution – because of the highly damaging impact that particulates from diesel are having on human health, but also because of climate change. The decline of diesel vehicles is unstoppable – just look at Norway as the trailblazer here, with 30% of all new car sales in 2018 already electric vehicles. The implications of this transformation have not been adequately thought through here in Malaysia, as the industry fights like fury to maintain access to the EU biodiesel market – a market that is going to be a great deal smaller in 2030 than you may imagine.

This shift cannot be dismissed as gesture politics on the part of rich European countries. Earlier in the year, the province of Hainan in China (with a population of nine million) announced that Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles will no longer be sold, as of next year, with a view to eliminating all ICEs in the province by 2030. At the same time, it is rapidly installing one of the most comprehensive charging infrastructures for Electric Vehicles anywhere in the world.

Lack of proportionality

In the medium term, however, the prospects for palm oil are good, not just because of the many inherent qualities of palm oil (which will be very well known to all of you!), but because demand for palm oil and its derivatives is still growing, particularly in China and India. Few analysts believe that this trend is likely to abate anytime soon. That’s the market reality, and it makes little sense for anti-palm oil campaigners to seek to wave it away as if it was of no importance.

One of the most important elements in our High Carbon Stock Science Study was to remind stakeholders in Europe and elsewhere that any serious sustainability analysis must take into consideration all vegetable oils, not just palm oil. In terms of tonnes of oil produced per hectare, oil palm produces around 3.5 tonnes in comparison to soybean oil at around 0.5 tonnes, sunflower oil at 0.6 tonnes and canola at 0.75 tonnes. In other words, oil palm productivity is seven times that of soybean, six times that of sunflower, and five times that of rapeseed. As one of the principal contributors to our Science Study, Dr James Fry (cited by Raison et al., 2015), pointed out at the time:

‘If any lost palm output was to be made up solely from extra soybean, the soybean area would have to rise from 111 million ha in 2013 to 232 million ha in 2025. If canola fills the breach, its area would have to rise from 36 to 109 million ha. For sunflower, the area would have to rise from 26 to 87 million ha.’

These comparisons are insufficiently recognised by European politicians, let alone by most European citizens. It is deeply irritating having to listen to those politicians justifying their dependence on scientifically-flawed Indirect Land Use Change (ILUC) assessments (to determine whether or not an oil should be judged high risk or low risk) whilst completely ignoring another kind of ILUC – the Indirect Land Use Consequences of any wholesale substitution of one oil for another. The consequences for Brazil’s already severely damaged Cerrado, in trying to develop an additional 121 million ha of soybean by 2025, would be utterly devastating. In those circumstances, even the European Commission (EC) might acknowledge, from the point of view of eliminating deforestation, that the risks associated with soybean are as high if not higher than those associated with palm oil.

As land becomes more and more scare, and competition for access to that land becomes ever fiercer, it’s clearly a priority to meet that growing demand for vegetable oils as efficiently as possible, with the lowest possible emissions of greenhouse gases, using as little land as is necessary. Suppress the use of palm oil in favour of its significantly less efficient competitors, and the indirect sustainability impacts will, I believe, turn out to be much worse than the impacts of sourcing that palm oil in a genuinely sustainable way.

That is why WWF International, for instance, has been very clear about the undesirable consequences of boycotts or outright bans: ‘Boycotts of palm oil will neither protect nor restore the rainforest, where companies undertaking actions for a more sustainable palm oil industry are contributing to a long-lasting and transparent solution.’ (Chan, 2018) And it’s why the World Alliance of Zoos and Aquariums has been so progressive and smart in choosing to educate visitors to many of its zoos regarding the difference between sustainable and unsustainable palm oil, rather than opting for the easier line of outright condemnation.

These unambiguous positions compare very favourably with the inconsistent and deliberately opaque positioning of Greenpeace and other Western NGOs.

The lack of proportionality and factual accuracy in dealing with these issues remains surprising. It doesn’t matter how many times one repeats it, but calculations as to relative causes of continuing deforestation are rarely included in the debate about palm oil. As you know, production of beef, soybean, palm oil and forestry products account for the largest share of tropical deforestation (around 27%), with beef production the biggest single driver of deforestation in every Amazon country, accounting for around 80% of current deforestation rates in Brazil. Soybean cultivation is the second major driver of deforestation in the Amazon basin – at a scale that dwarfs continuing deforestation for palm oil in Southeast Asia. These realities are almost entirely unknown to the vast majority of European citizens.

In April, Global Forest Watch released its data for tree cover loss in 2018. (Tree cover loss is not the same as deforestation, as it includes areas lost to fire, disease and other natural disturbances, as well as timber harvesting and oil palm replanting operations.) At 440,000 ha (which includes 144,000 ha of primary forest tree cover), total tree cover loss in Malaysia in 2018 was around 15% lower than the average over the previous 10 years (Global Forest Watch, 2019).

And it doesn’t matter how many times one points out that the threat to the orang utan in Southeast Asia is not quite as horrendous as implied in stock campaigning materials.

But let us be clear here: that figure is still far too high, and one which campaigners are right to continue to highlight. Just as they’re right to expect producers to meet all their obligations through RSPO certification, to manage their supply chains more rigorously, to eliminate all bad actors from those supply chains, and so on. That, it seems to me, is precisely what responsible, effective campaigning NGOs should be doing.

But at some point in the last few years, an honourable record of campaigning to improve the industry’s performance (however uncomfortable that may have been to many in the industry itself) spilled over into what I call ‘the generic demonisation’ of palm oil per se. It was no longer a problem caused by ‘bad actors’ in the industry, but of the product itself. The decision last year by the UK retailer Iceland to remove all palm oil from its own-brand products was based on the judgement of its CEO, Richard Walker, that it was not possible to distinguish between CSPO and uncertified oil. Not to put too fine a point on it, as I pointed out at the time, that is an example either of startling ignorance or wilful mendacity.

Since then, the iconic London store, Selfridges, has gone down the same route, a highly regrettable decision in my opinion. But these examples are but the tip of the iceberg regarding the use of ‘palm oil free’ labels becoming all too common in many European countries.

Greenpeace’s hugely successful film, ‘Rang-tan: the story of dirty palm oil’, unapologetically endorsed that same view, blatantly manipulating children’s (and adults’) emotions through the representation of a baby orang utan, making no effort whatsoever to distinguish between certified sustainable and uncertified oil.

Just as worryingly, the decision earlier in the year on the part of Norway’s pension fund to de-list all the remaining palm oil companies in its portfolio was a further manifestation of generic demonisation. How the Trustees of the Fund suppose that this will serve the interests of their beneficiaries I do not know – though it certainly secures an easier life for those Trustees. Blanket condemnation is always so much easier than exercising one’s critical faculties.

How can we account for this sorry state of affairs? For sure, campaigners in the West have become increasingly impatient with the degree to which the ‘bad actors’ in the industry have continued to act with impunity – or even ‘immunity’, given how reluctant politicians have been to put an end to their flagrant disregard for the environment, for climate change, for workers’ rights, local communities and indigenous people.

But that’s too easy an explanation. I spend endless hours reading press releases and reports from both Western NGOs and representatives of the Malaysian industry, and I am (perhaps naïvely) astonished at how little readiness there is to acknowledge any validity regarding the case made by those on the other side.

I would, for instance, be so delighted to hear a single European NGO acknowledge that much of the campaign against palm oil in Europe is driven by straightforward protectionism on the part of Europe’s very powerful vegetable oil trade associations – for canola and sunflower oil. How can it help consumers in Europe to come to a balanced view of this without bringing that incontrovertible reality to their attention, each and every time the debate is joined?

By contrast, why do we never hear from leaders in the industry in Southeast Asia that their constant efforts to protect and build markets in the West are inevitably undermined by those ‘bad actors’ in the industry? The current efforts being made by RSPO-certified companies to clean up their supply chains represents a de facto recognition of the damage done by those bad actors, but it’s never quite spelled out with the clarity that would be helpful in terms of influencing Western opinion.

(By the way, it’s worth pausing to acknowledge that those efforts – to clean up supply chains – are quite extraordinary. In the last two or three years, supply chain mapping has moved forward dramatically, as has risk assessment analysis, and we’re just beginning to see the fruits of that combined industry endeavour to manage these uniquely complex supply chains.)

But it goes deeper than that, as we all know. I’ve read the speeches by Malaysian Minister of Primary Industries Teresa Kok Suh Sim and Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad attacking the highly controversial decision by the EC (at the behest of uncompromising Green MEPs in the European Parliament) to phase out the import of palm oil for biodiesel in Europe. They (and their Indonesian counterparts) are basing their arguments on the case that the EU’s decision is not only directly contrary to WTO rules, but directly contrary to the EU’s support for the SDGs – highlighting in particular the impact the new measures will have on smallholders in both countries. It is indeed most regrettable that so many politicians in the EU choose to cherry-pick the SDGs in this way.

Although I am not convinced that seeking an all-out war with the EU is the most sensible way to proceed, I have a lot of sympathy for the case that is being made here. I have learned over the last few years that many Western NGOs and politicians have very little understanding of the socio-economic contribution of the oil palm industry to the economic success of both Malaysia and Indonesia, both historically and today. I cannot honestly recall a moment where these economic considerations have been taken into account as the arguments rage back and forth about deforestation and the plight of the orang utan.

As a result of which, I have come to the disconcerting conclusion that some Western NGOs are influenced, directly or indirectly, by a form of eco-colonialism. That is not a charge I lay lightly, but it is indisputably there in the way they think and act, and it is deeply problematic.

Significant shifts required

So let’s step back for a moment, given the need to reconcile two absolute imperatives: a market imperative that the world needs a secure supply of traceable CSPO; and the environmental imperative that the world needs a complete halt to any further clearance of primary or mature secondary forest, from both a climate change and a biodiversity point of view. How do you suppose historians will be reflecting on these issues from the vantage-point of, say, 2040 or 2050?

If things continue as they are, whatever the rights and wrongs of the current, ever more painful controversies, my sense is that they will be reflecting, first and foremost, on an unprecedented opportunity missed. An opportunity to reconcile the wholly legitimate interests of responsible palm oil producers, with the need to eliminate further deforestation, and to protect the rights of all those working in the industry, at every level.

But is it too late to seize hold of that opportunity? Here in Malaysia, I would like to suggest that it is not. Indeed, almost all of the elements required to make it possible are already in place, in varying degrees as discussed below:

1. The Malaysian Government is firmly committed to preventing further deforestation, to improving the level of protection for the 50% of its land that is still in natural forest, and putting an upper limit on the amount of land which will be dedicated to oil palm cultivation.

2. The Malaysian Government has set a target for all producers (including smallholders) to be certified to the MSPO standard by the end of this year. Whilst it is true that the MSPO is not as rigorous as the standard set by the RSPO, it is an internationally- approved standard which significantly raises the bar in terms of environmental and social safeguards. It would be an astonishing achievement for the industry to meet that target.

3. The state of Sabah is pursuing a strategy to ensure that all oil produced anywhere in the State should be CSPO. This would be the first of a number of ‘jurisdictional approaches’ that are currently being pursued in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

4. Leading Malaysian companies have reaffirmed their commitment to NDPE – no deforestation, no development on peat, and no exploitation. And, as I’ve already mentioned, a significant investment is being made in assessing the risk of deforestation in their supply chains, and in implementing appropriate management strategies to put an end to that deforestation.

5. There are a number of forward-looking NGOs (including Conservation International, WWF International and the World Resources Institute) that are fully cognisant of the critical socio-economic role the industry plays in Southeast Asia and, increasingly, in other countries in West Africa and South America. They are keen to help broker a new ‘compact’ with the industry that would deliver mutually-reinforcing objectives around biodiversity and climate change.

6. Steady and continuing improvements in satellite monitoring means that it is now possible to detect any deforestation going on, on the ground, at an extraordinary resolution. ‘Total transparency’ is the new reality for plantation growers and smallholders alike. This is often seen as a technology that works against the interests of growers, but why shouldn’t governments (at state and federal level) make use of these massively important technological developments to enforce their own policies, rather than seeing this either as a threat or as an unwarranted intrusion into the sovereign rights of governments to determine all land use decisions in their territories?

7. There is now widespread, near-universal acceptance that all future growth in the Malaysian industry needs to come from increasing yields rather than from increasing the land bank available for oil palm. Average estate productivity has improved very little over the last 30 years, and is still stuck at around 20 tonnes of fresh fruit bunches per ha – with smallholder yields significantly lower than that. Increasing average production to 30 or even 35 tonnes per ha is obviously a huge challenge, but all the people I managed to speak to before undertaking this Lecture are very clear that it can – and should – be done as a matter of urgency.

8. Despite the less than impressive performance of members of the Consumer Goods Forum (for the majority of whom a commitment to ensuring ‘deforestation-free supply chains by 2020’ apparently depended on everybody else making it happen on their behalf, even as they did nothing to pay the true cost of making palm oil more sustainable), there are now a number of major companies (including Unilever and Nestlé) which are intent on securing access to sustainable palm oil over the long term, with an emphasis on shared value rather than cut-throat, short-term contracting.

9. The RSPO, despite all the criticism it has to cope with both from Western NGOs and the industry itself (surely some measure of continuing effectiveness for any multi-sector organisation!), has now significantly improved the Principles and Criteria on which any new developments in Malaysia will be approved. Though pretty much unsung on any side of the debate, the RSPO’s continued brokerage role should remind us that progress through negotiated compromise (and I use that word advisedly and not disparagingly) works a lot better than constant confrontation.

So, what are the chances of aggregating all of these different elements into a new initiative here in Malaysia, to get us all out of the embattled positions that people currently feel they have no alternative but to defend? To learn, perhaps, from what’s been happening in Colombia, where sector leaders in the industry joined forces with the Norwegian and UK Governments, as well as a number of prominent NGOs, to sign the first-ever ‘Zero Deforestation Agreement for Palm Oil’ back in 2018? This will require a radical change of heart on the part of all major protagonists to achieve something similar here in Malaysia.

First, Western NGOs such as Greenpeace, Rainforest Action Network, Mighty Earth and so on, will need to recognise that there is a bigger ambition level they should be signing up to rather than sticking with the relatively easy option of endlessly attacking not just ‘the bad actors’ but even those intent on meeting the highest possible standards across their supply chains.

I first felt this kind of frustration during the complex process of reconciling different positions on what is meant by ‘zero deforestation’ during the High Carbon Stock Science Study: any deviation from an impossibly restrictive definition of zero deforestation was characterised as ‘betrayal’ or a sell-out to an industry that is deemed by some to be impossible to trust.

Nearly four years on, I hope those NGOs can now see that this absolutism may not have served them as well as they hoped. Instead of publicly standing up for those companies intent on fulfilling their NDPE commitments, within a reasonable period of time, they’ve become the multipliers of today’s generic demonisation. And the principal consequence of that is that many companies are now re-thinking their market orientation: if every effort they make is met with scepticism, hostility or indifference, leaving the majority of consumers in Western markets persuaded that oil palm is ‘a bad thing’, then why go on bothering?

There is now a widespread belief that more and more companies (particularly in Indonesia) will cast off the constraints of international certification through the RSPO, and focus instead on domestic biofuel markets, as well as exports to China, India, Pakistan and so on – where (for the time being, at least) companies and consumers would appear to have fewer scruples about forests, biodiversity, indigenous people and poor employment practices. From the point of view of accelerating climate change and continued biodiversity loss through deforestation, this is a complete disaster.

By the same token, we would need to see significant shifts in the industry itself, both from producers and consumers. All the ‘good actors’ in the oil palm industry today can no longer stand by as the ‘bad actors’ in their industry continue to put at risk all their ambitions for significant growth in value-adding Western markets. In a world of ‘total transparency’, with satellite technology and the power of big data leaving nobody with any room to hide, this is now the operating reality for the industry as a whole.

Trade bodies need to accept that reality, resisting the temptation to play off MSPO certification against RSPO certification, doubling down in their efforts to support smallholders through improved extension services and new financing mechanisms to enable replanting, and concentrating research budgets on the all-important challenges of improving yields, increased automation, and ensuring resilience in the face of accelerating climate change.

On the consumer side, as I’ve already suggested, both manufacturers and retailers need to deliver on their commitments to ensure deforestation-free supply chains, unequivocally accepting the need to pay a fair premium for traceable, certified sustainable oil, rather than expecting producers in countries much less well-off than themselves to bear that cost on their own.

But the most important player in all of this is, of course, the government, and here I find myself in an ambivalent position: even though part of my mission is to explain to environmentalists in Europe what’s actually going on here in Malaysia (including the commitment to continue to protect the 50% of its territory that is still in natural forest – in comparison, by the way, to the UK’s rather miserable 13%!), I know that the enforcement of that policy is not as rigorous as it should be, and that there is significant encroachment in many of those protected areas. There is no doubt that gazetted forest reserves are being illegally cleared, to within 20 or 30 metres of the boundary of those reserves to conceal the extent of that deforestation.

And despite its best intentions, the Malaysian Government has been slow to move against the bad actors in the Malaysian industry, however problematic it may be to enforce the high standards it seeks uniformly across the entire country. And is there any case at all, given the very welcome emphasis on yield improvement and support for smallholders, to release any more forested land for new oil palm development?

So, no shortage of challenges! But the prize here is enormous: to become the first major producer country in the world able to market every last tonne of oil produced on Malaysian soil as genuinely sustainable, from both an environmental and a social point of view, with traceabilty to the point of origin as a critical element in substantiating that claim, with RSPO certification to back its value-adding export credentials, and MSPO certification for domestic markets (including biofuels) and bulk commodity sales.

After years of confrontation, this may seem unrealistic – and the international community would indeed need to lend its weight to a transformative commitment of this kind. But is there any good reason why the Norwegian Government should not be prepared to back a ‘super-jurisdictional’ approach of this kind, particularly in terms of supporting ‘produce and protect’ measures in both Sabah, and even more importantly, in Sarawak – which has yet to identify itself with a nationwide endeavour of this kind.

And should this not be an absolute priority for the Tropical Forest Alliance, as it seeks to make good on the lofty declarations it made when it was first launched in 2012 – hopefully with the enthusiastic support of my own government’s Department for International Development?

This must surely be a worthy call to action: to bring together all relevant stakeholders to put in place an overarching ‘Sustainable Economic Strategy’ for the industry as a whole by the end of next year? In that regard, I have no doubt that this august body, the Incorporated Society of Planters, will be keen, in its 100th anniversary year, to play its part in bringing together all those parties on whom the industry’s continuing success over the next 100 years so clearly depends.

References

CHAN, H. 2018 ‘Palm Oil Boycotts Not the Answer’, WWF Malaysia, Dec 7, 2018.

http://www.wwf.org.my/?26425/Palm-Oil-Boycotts-Not-The-Answer

GLOBAL FOREST WATCH, 2019 (online only) Country dashboard: Malaysia

https://gfw2-data.s3.amazonaws.com/country-pages/country_stats/download/MYS.xlsx via

https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/global

RAISON, J, ATKINSON, P, BALLHORN, U, CHAVE, J, DeFRIES, R, JOO, G K, JOOSTEN, H, KONECNY, K, NAVRATIL, P, SIEGERT, F, STEWART, C. 2015 ‘HCS+: A New Pathway to Sustainable Oil Palm Development: Independent Report from the Technical Committee’. Kuala Lumpur: The High Carbon Stock Science Study.

http://www.simedarbyplantation.com/sites/default/files/sustainability/high-carbon-stock/hcs-iIndependent-report-technical-committee.pdf

SANCHEZ-BAYO, F, and WYCKHUYS, K A G. 2019, ‘Worldwide Decline of the Entomofauna: A Review of its Drivers’. Biological Conservation, 232 (April 2019): 8-27.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320718313636

WORLD COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT, 1987 ‘Our Common Future’. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

By gofb-adm on Monday, June 24th, 2019 in Issue 2 - 2019, Special Report No Comments

By gofb-adm on Sunday, June 25th, 2017 in Issue 2 - 2017, Special Report No Comments

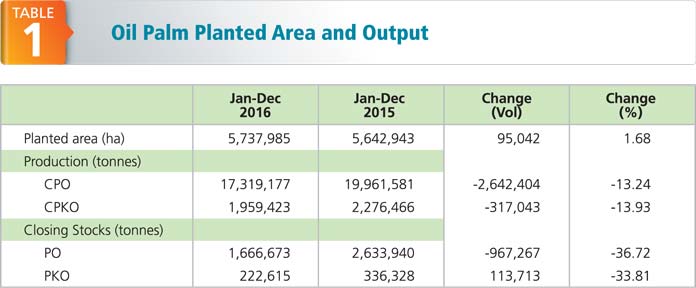

Malaysia’s oil palm acreage grew to 5.7 million ha in 2016, marginally up by 1.7% compared to 5.6 million ha a year earlier (Table 1). Severe drought induced by the El Nino phenomenon in the second and third quarter of the year severely impacted palm oil production.

Source: MPOB – data as at February 28, 2017; subject to revision

As a result, crude palm oil (CPO) production was down by more than 2.6 million tonnes (13.2%) compared to 2015. Weather conditions improved in the second half of the year, but did not help make up the production losses sustained in earlier months. Crude palm kernel oil production was not spared either by the impact of El Nino, with output falling by 317,043 tonnes (13.9%).

Although there was some recovery in palm oil production over the last four months of the year, most plantations reported tree stress. This reduced overall output despite the increase in planted area. Palm oil ending stocks were recorded at 1.7 million tonnes compared to 2.6 million tonnes in 2015, down by 36.7%. Palm kernel oil stocks fell to 222,615 tonnes (by 33.8%) against 336,328 tonnes a year earlier.

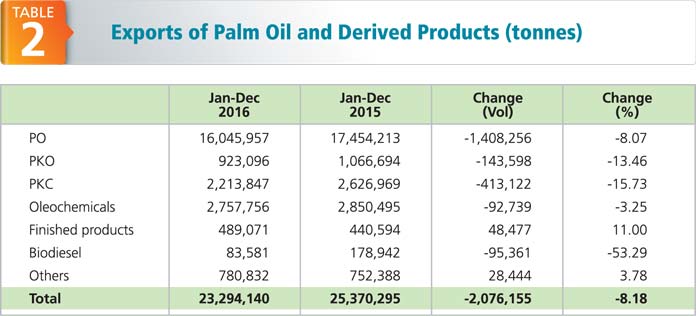

The production shortfall led to slightly lower exports of palm oil and derived products. At 23.3 million tonnes (Table 2), this was a drop of 2.1 million tonnes (8.2%). Reduced volumes were registered in exports of almost all categories of palm-based products. Palm oil fell by 1.4 million tonnes (8.1%); palm kernel oil by 143,598 tonnes (13.5%); palm kernel cake by 413,122 tonnes (15.7%); and biodiesel by 95,361 tonnes (53.3%).

Source: MPOB – data as at February 28, 2017; subject to revision

However, the export volume of finished products rose by 48,477 tonnes (11%), while other products accounted for an additional 28,444 tonnes (3.8%) during the year.

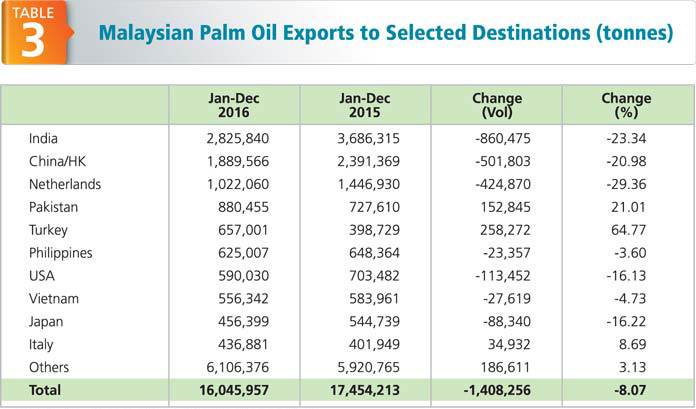

Demand for Malaysian palm oil continued to be driven by strong consumption in India, China, EU-28, USA and ASEAN member-states (Table 3). The top 10 importing countries and regions took up 9.9 million tonnes, or 62% of the 16 million tonnes exported. A significant increase in Malaysian palm oil imports was seen in Turkey, Pakistan and Italy.

Source: MPOB – data as at February 28, 2017; subject to revision

India remained the biggest importer even though it absorbed 860,475 tonnes (23.3%) less than in 2015. Its intake of 2.8 million tonnes made up 17.6% of Malaysia’s palm oil exports. China/HK’s imports of 1.9 million tonnes, while still substantial, represented a drop in demand of 501,803 tonnes (21%). This was due to higher domestic crushing that produced an estimated 90 million tonnes of rapeseed oil, against 70 million tonnes the previous year.

By gofb-adm on Monday, December 5th, 2016 in Issue 4 - 2016, Special Report No Comments

Duncan, Farooq,

Wimmer et al

DAfz

This is an executive summary of a policy study carried out in 2015 by academics of the German Asian Research Centre into the effects of campaigns by Transnational Non-governmental Organisations (TNGOs) and Direct Action Groups (DAGs) that are targeting Southeast Asia’s palm oil industry.

The study – ‘Debunking Non-profit Campaigns & Economic Impacts on Malaysia’ – considers, in particular, the resulting negative social and economic implications for Malaysia as a major producer of palm oil.

The findings reveal that TNGOs are determined and well financed. Their actions are motivated by self-righteous, often implicitly religious ideals from the Global North that aid in the pursuit of their hostile campaigns. Geopolitical strategies to trigger economic and political regime changes often accompany such transnational activism.

These groups act as political movements originating in the Global North, while pursuing a strategy to undermine and dominate the making of environmental, social, political and economic policy in Southeast Asian countries, among others.

Environmental activism, just like terrorism and human trafficking, has become one of the most polarising themes for Southeast Asian nations, as well as for their policy makers, leaders of industry and citizens. No longer is environmentalism just a struggle to save the planet; it has also become a tussle to change fundamental social values and legal relationships among and within these nations.

On May 31, 2016, Greenpeace International and some of its associated groups were charged in the US Federal court with 11 counts of federal and state offences under the organised crime act – informally dubbed the ‘mafia law’. Greenpeace faces charges of criminal racketeering, conspiracy to commit a felony, and mail and wire fraud. Many of the activists targeting Asian companies were named in the lawsuit; this highlights the changing nature of TNGOs and DAGs.

In Canada, an equally bitter legal battle is going on between Greenpeace and the industry. In India, Greenpeace and others have been declared a threat to national economic security

The study examined a compelling body of evidence showing how the attack on the palm oil industry is akin to the:

Recognising the political nature of the campaign against the Indonesian palm oil industry that has targeted consumer and producer markets, the severity of the threat to Malaysia and its palm oil industry should not be under-estimated.

The economic costs alone will be substantial. A key finding of the study is that Malaysia will lose an estimated US$11.5 billion, or 3-3.5% of its GDP per annum, as the direct result of negative TNGO campaigning. Neighbouring Indonesia has experienced a similar loss.

War by other means

The highly structured and well-funded campaigns implemented by a range of TNGOs employ a number of strategies, such as product Boycotts, Divestment and Sanction campaigns discrediting the Malaysian state and palm oil companies.

Dismissing the potential geo-economic implications as unlikely – simply because they do not fit within the confines of economic rationality (Blackwill, 2016, p.14), business reasoning or policy logic – is discounting risks when it comes to affairs of the TNGO sector.

This is part of a strategy that reflects the new political reality – the intertwining of the interests of Global North nations and a limited group of zealots pursuing an ideologically rooted, anti-development narrative. Exaggerations, over-inflating impacts and misrepresentation of facts are common tactics in use against the industrial ‘targets’.

According to Frances Seymour, a Senior Advisor to the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Climate and Land Use Alliance, the use of funding from foreign philanthropic foundations, mostly industrial legacy foundations, has this advantage: ‘Compared with public funding sources, private philanthropy is less constrained by political sensitivities’ (Seymour, ‘Reducing Emissions from Oil Palm Cultivation in Indonesia’, 2014, p.23). Therefore, this funding may be used for purposes that would be highly problematic if public funds were used in a similar fashion.

In addition, foundations are in a position to fund actions over multi-year periods (Seymour, 2014, pp.28-29). The policy study identifies many of the foreign foundations, as well as recipients of the subsidies in Malaysia.

By definition, the strategies employed by TNGOs and DAGs – also known as the Global Action Network – constitute ‘asymmetrical warfare’, defined as action ‘… [i]n which opposing groups or nations have unequal military and economic resources, and the weaker opponent uses unconventional weapons and tactics, [as terrorism], to exploit the vulnerabilities of the enemy strategies pursued by the enemy’ (Dictionary.com, 2015).

As evidence from the study shows, environmental activists employ the terminology of ecological and economic warfare interchangeably. The martial concepts are used as constant references by:

By employing asymmetrical strategies, relatively weaker entities such as TNGOs are able to overcome their opposition, although the latter – the nation-states – have greater resources to engage in conflicts. The policy study documents the use of military strategies by environment groups in campaigns against the Malaysian palm oil industry. This, in turn, challenges the nation’s sovereignty and the “rule-based order” (Blackwill, 2016, p.15).

Seymour, the architect of adversarial strategy for the Packard Foundation, wrote (2014, p.6):

‘Consumption is primarily in Asian markets, dominated by Indonesia, India and China, where palm oil is used as a staple cooking oil. The more environmentally sensitive markets of Europe and the United States have smaller shares of the global market but are disproportionately important to the industry due to higher value derivatives and the potential for growth.’ [emphasis added]

The statement, in fact, provides an insight into the reasoning underlying the strategy and the recognition that the small size of the markets in Europe and the US provides the Malaysian industry a vantage point. By understanding the strategy behind the global initiatives, Malaysian policy makers are well positioned to formulate a justifiable counter-strategy.

By focusing negative campaigning on the customers – both public consumers and multinational corporations – of palm oil, TNGOs are able to apply considerable economic pressure on Southeast Asia’s producers.

The study concludes that the size, aggressiveness and potential economic consequences of hostile foreign campaigns will require prompt and decisive intervention by the government, regulatory ministries, palm oil producers and the media, in order to counter what realistically is economic warfare against the State and the palm oil industry.

Fortunately, Seymour’s report (2014, p.16) goes on to identify the vulnerability of the strategy:

‘The main limitation of strategies focused on direct engagement with producer companies is that the ability to translate individual company commitments into sector transformation has not yet been proved. As long as irresponsible companies are able to enjoy the impunity made possible by poor governance and insensitive markets, the “flipping” of specific individual companies one by one will be a long and increasingly difficult task. [emphasis added]

The lack of a second producer company to follow the lead of GAR [Golden Agri Resources] for several years after the announcement of its Forest Conservation Policy in February 2011 casts doubt on the potential of even a large, well-connected company to catalyse sector transformation.’

Her admission that “flipping” individual companies may not produce the desired results allows for a wide range of responses that are available to policy makers and industry management.

It also brings into question the strategic thought process on the part of adversarial TNGOs which support the view that the concept of ‘alternative markets’ is ultimately ineffectual, unless bolstered by broad social sector support. The study documents a lack of broad social support for this strategy in Asian markets, as well as markets in Europe and the US.

A resolute response is required in order to reclaim the value of the Malaysian palm oil industry, and the study makes recommendations for actions to defeat the adversarial strategy.

Policy and industry responses

The transnational activists and militant environmentalists are increasingly coming under fire from political leaders in Asia who are beginning to recognise the harmful potential of these movements.

On Sept 2, 2015, the Indian government stated that Greenpeace, other NGOs and some donors are prejudicially affecting the public and economic interests of the country, while delaying and placing illegal obstructions in the path of its energy plans (Singh, ‘Greenpeace India’s registration cancelled’, 2015).

Indonesia has associated activism with proxy wars (Kompas, 2014) and as a latent threat to society (Doull, 2015); while the Malaysian Academy of Science suggests that the negative campaigns by NGOs are tantamount to deliberate sabotage (Ibrahim A, 2015).

As stated earlier, Greenpeace US and Greenpeace International face charges under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organisations Act. If found guilty, Greenpeace will be a designated criminal enterprise under the anti-mafia, drug cartel and terror legislation (Resolute Forests Products (et al) vs Greenpeace International (& et al), 2016). The implications for policy, industry and the civil society movement is significant.

The study argues that the time is ripe for Malaysian palm oil to reassert itself as an industry leader, and for its government to reclaim control over the destiny of an important sector that contributes so much to the GDP. Since colonial times, palm oil has been considered a strategic resource – for employment, tax revenue, economic development and social stability – in Malaysia. Therefore, whatever affects palm oil negatively must be viewed as a matter of national security.

The study also contends that the interests of national security, if not faced with armed threats, is faced with economic, political, and social threats from TNGOs. It documents alliances that these groups have formed with local and regional militant organisations that are determined to transform the political and economic sectors, the status of indigenous communities, poor communities and other social sectors.

Morphing of activist groups

Greenpeace and many other TNGOs insist that they are political (ecological) movements (Wyler, 2015). Therefore, this study treats the NGOs targeting Malaysia as such.

Lord Robert McCredie May, the former government chief scientific advisor and president of the Royal Society in the UK, said Greenpeace has “transmogrified” into primarily an anti-globalisation movement (Randerson, 2009). The study shows how some conservation groups have morphed into environmental movements and morphed once more into the anti-modern, anti-globalisation movements to which Lord May refers.

Different terms have been applied to these militant organisations – terms like ‘transnational’, ‘cross-border’ or ‘global’ – and designations are rife in academic and policy circles. Technically, Greenpeace and the TNGOs are ‘trans-state’ movements (Fox, 2005); they, therefore, pursue trans-state objectives. And, as this study shows, they are intent on abolishing nation-states and fulfilling the perennial radical socialist dream of a single world government.

To accomplish this dream, the TNGOs – in the context of mass appeal – adopt a policy of encouraging fear and anxiety among citizens around the world. Their product is worry – because worry is what recruits members (Randerson, 2009). What began as a mission to improve the environment for the sake of humanity is today a political movement. Humanity has become the villain, and the need to present hard evidence is a non-issue (Prager, 2015).

These movements place science in the service of ideology. As far as economic development and the idea of progress are concerned, Greenpeace and the NGOs have declared ‘war’ on both – terminology that was deliberately chosen (Confino, 2012).

Since such terminology is not unlike that employed by the Holy Inquisition, Communists, Nazis, Jihadists or Khmer Rouge; it is a language of the extreme (Fiorina, 1999). A new ‘apocalypticism’ based on the end of the world – and encapsulated in the mantra ‘climate change’ – is the tool these groups employ. Dr Sharon Eng wrote (‘Rogue NGOs and NPOs: Content, Context, Consequences’, 2014):

‘A rich literature review of major and minor non-profit scandals – primarily in the West – but also in other countries around the world demonstrate the breadth and depth of non-profit corruption, fraud and misuse of funds as well as misconduct and deviant behavior by individuals within and by organisations. These associations range from Mom and Pop-scaled voluntary foundations to trans-national charitable organisations to trans-national charitable organisations, and so-called ‘Dark Non-profit Groups’ that promote terrorism, hate, extreme political views and other noxious or bizarre ideologies … Consequences of non-profit organisational misconduct and dysfunction reveal a universal need for more research into the dark side of the Third Sector…’

They terrorise and manipulate individuals in order to justify their new world order – one that looks to the past for inspiration, when the human population of the planet was sparse and lived at the subsistence level.

Scholars of social movements no longer consider them as irrational groups or the actors as spontaneous; they assume that TNGOs and DAGs are making rational, tactical and strategic choices (Dalton, 2003).

The result is that a comprehensive, deliberate and premeditated strategy of insurgency is being employed to target the Malaysian palm oil industry, among others, using militant and asymmetrical action (Moss, 2014).

The respectable CIFOR has raised the question of the use of military decentralised decision-making processes being used in conservationism. The reference is linked to the latest edition of the US Army Field Manual on Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies (Moss, 2014).

The evidence presented in this study shows how a global network of actors and interests (Glasbergen, ‘Global Action Networks: Agents for collective action’, 2010) has acted in collusion (Pruyt, 2014). The Global Action Network refers to activists as ‘Change Agents’ or ‘Agents of Change’, but they increasingly act more in line with common radicals. Canadian researchers refer to the movements as ‘multi-issue extremists’ (Monaghan, 2011).

The evidence analysed in this study prompts the question: Are the choices that TNGOs and DAGs make actually out of a concern for the health of the environment?

In the case of Greenpeace’s actions in Russian waters where arctic oil exploration was underway, and in India where energy requirements prompted the use of technology using coal to generate electricity, the strategic thinking of the NGO and its funders backfired. This affected international relationships and triggered negative reactions by these countries. Today, in a growing number of nation-states, activism is seen as a threat to national economic security.

Environmental groups face a dilemma: they have to choose between fundamentalism, extremism, expressive activities and pragmatic, instrumental activities.

According to the first perspective, environmental movements are seen as advocates of a broad-scale critique of the political and social system. The core ideological beliefs of the environmental movement challenge the dominant norms and practices of capitalist (and state-owned) economies and the presumption that economic growth underlies these societies (Dalton, 2003).

For radical environmentalists, ‘progress’ is transmogrified to ‘regress’, and ‘sustainable’ becomes ‘subsistence’. Thus, with the invention of a new terminology and militancy, they seek to transform values and achieve unchallenged power over the strategic resources of countries like Malaysia.

The full study, currently being peer-reviewed and readied for print, is available on request from the authors, as well as at:

By GOFB on Friday, September 30th, 2016 in Issue 3 - 2016, Special Report No Comments

Economic analysis shows clearly that the current situation in France in relation to taxation of palm oil is as follows: • Palm oil is taxed at a higher rate than all domestic oils – rapeseed, sunflower and olive oils. • The situation is clearly discriminatory against palm oil.

Read more »By GOFB on Friday, July 22nd, 2016 in Issue 2 - 2016, Special Report No Comments

Malaysia’s oil palm acreage expanded to 5.64 million ha for the year under review, up by 4.63% compared to 5.39 million ha previously (Table 1). Floods towards the end of 2014 left a severe impact on palm oil production. As a result, crude palm oil (CPO) output registered 9.04 million tonnes for the first half of the year, but rose to 10.92 million tonnes in the second half with improved weather conditions and reduction of tree stress.

Overall CPO output went up to 19.96 million tonnes, or by 294,628 tonnes (1.5%), over the comparative period. This was due to recovery in the production of fresh fruit bunches that also showed better quality; as well as the maturing of newly-planted areas especially in Sabah and Sarawak. The volume of crude palm kernel oil fell slightly by 916 tonnes or 0.04%.

Palm oil ending stocks increased, closing at 2.63 million tonnes in December or 38.46% higher year-on-year. Palm kernel oil closing stocks stood at 0.34 million tonnes or an increase of 12.48%.

Export demand for palm oil and derived products was 1.19% higher, with the volume going up to 25.37 million tonnes from 25.07 million tonnes a year earlier (Table 2). Palm oil made up the bulk of exports at 17.45 million tonnes, compared to 17.31 million tonnes previously.

Oleochemical exports increased slightly by 0.78%, going up to 2.85 million tonnes from 2.83 million tonnes a year earlier. This was mainly due to higher demand from the EU-28, China, USA and Japan. Reversing the 2014 scenario, biodiesel exports more than doubled to 178,942 tonnes (by 104.84%), but exports of finished products went down to 440,594 tonnes (by 2.01%).

Malaysian palm oil exports increased by 147,966 tonnes (0.85%). The top 10 importing countries and regions (Table 3) took up 11.5 million tonnes, or 66% of the 17.45 million tonnes exported.