Headwinds across the Balkans

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Markets No Comments

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Markets No Comments

The Balkan Peninsula, in southeast Europe, reaches into the Mediterranean Sea and is named after the Balkan Mountains. The MPOC’s working definition of the region covers 11 countries, also dividing it into West Balkans and EU Members. Together, the countries have a population of over 60 million, ranging from more than 19 million in Romania to only 600,000 in Montenegro (Table 1).

Income levels in Western Balkans have been far lower than in the Balkans EU even before the Covid-19 pandemic struck earlier this year (Figure 1). The six countries are poor by almost any standard. Remittances from migrant workers in 2019, on average, reached an astounding 8.8% of GDP, according to a World Bank estimate. By way of comparison, the GDP per capita was €115,536 in Luxemburg, €78,335 in Ireland and €47,662 in Germany.

The coronavirus pandemic has, of course, made things worse. The economies of Western Balkans are suffering, supply chains are collapsing, and remittances may be cut off.

Bosnia and Herzegovina, Northern Macedonia and Serbia, as the more industrialised countries, are struggling with collapsing supply chains. The dependency of Serbia and Northern Macedonia on the European automotive industry is seeing challenges.

Montenegro and Albania, for their part, are struggling with reduced tourist numbers. Tourism accounts for about a quarter of the GDP of the two countries, and at least one in five employees derives income from this sector.

The economic growth forecast for Western Balkans was still positive at the end of 2019 (Table 2). Although the global economic engine had stalled, the region seemed to be able to withstand the headwinds and was expected to grow by an average of 3.4% in 2020. Then the pandemic hit.

Remittances, which form an essential pillar of consumption in Western Balkans, could be lost due to the coronavirus crisis. For some families, these serve as a supplement; for others, the only income they receive is from relatives abroad. Since the coronavirus crisis started, many employees have been on furlough or have lost their jobs altogether.

The situation is no better among EU Members of the Balkans (Table 3).

Bulgaria: After a long period of economic growth, the pandemic is paralysing the economy. Despite this, the political framework conditions – especially low tax rates – and the foreign trade orientation towards the European Union (EU) are still favourable enough to point a way out of the trough.

Croatia: The economy will suffer a severe setback. Economic recovery, which began in 2015 after years of recession, is now ending abruptly. The pandemic is causing a sharp drop in demand both at home and abroad. Measures to contain Covid-19 are severely restricting the ability of companies in the industry and service sectors to function. The consequences of the health crisis will be felt much more strongly in Croatia than in most other countries in Western Balkans and central and eastern Europe.

Greece: The GDP will fall by almost 10% in 2020, according to forecasts by the European Commission. The pandemic has shut down the economy. Greece had just overcome a 10-year crisis, which had robbed it of about a quarter of its economic strength. In 2019, GDP had grown by 1.9%. Now the outlook is gloomy again. The country’s debt will increase to almost 200% of GDP, and unemployment will rise from about 16% to 20%.

Romania: The government promises a fundamental reorientation of its economic policy. Instead of pro-cyclical and consumption-oriented growth, the state is relying on a new model for the next 10 years.

This will focus on:

Slovenia: After seven years of steady growth, the economy will shrink in 2020. The pandemic has drastically hit the open economy, which is strongly interwoven with Europe. Problems are being caused by a drop in foreign demand, especially from the EU. Domestic demand has also suffered severely. Pandemic-related restrictions have impaired the functioning of the transport and supply chains.

Despite the difficulties, the global coronavirus crisis could open up excellent opportunities across the Balkans in the long run. Globalisation and the inter-twined world economy are currently under attack from several sides. At the same time, European economies are considering whether to build up new production sites in Europe or to repatriate others from offshore. The thinking is that this would make them less vulnerable to crises. The keywords are nearshoring and reshoring.

From a western European perspective, nearshoring means production in eastern and southeast Europe. Western Balkans could become to the EU what Central America is to the US: an investment and supply location of great geopolitical and economic importance.

Bosnia and Herzegovina, Northern Macedonia and Serbia are particularly interesting locations for investments in industry. All three countries are competitive in terms of productivity and labour costs, and are geographically conveniently located right at the gates of the EU. There is a sufficiency of human resources. In countries of central and eastern Europe, such as Hungary or Slovenia, it is difficult to find workers.

Vegetable oils sector

Over the past decade, the Balkans have considerably expanded the production and export of vegetable oils (Figures 2 and 3).

In 2019, the Balkans imported over 282,000 tonnes of palm oil, up from 191,000 tonnes in 2009.

In 2019, Malaysia contributed 97,724 tonnes of palm oil products (Figure 5). Palm oil and biodiesel accounted for more than 75% of the volume. Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia and Greece together absorbed 92% of the imports (Figure 6). All of the 30,000 tonnes of biodiesel imports went to Bulgaria.

Over the first half of 2020, the impact of Covid-19 left its mark on the region’s palm oil imports. With the exception of Greece, all major importers recorded a drop in demand (Figure 7).

However, economic experts foresee strong recovery from 2021. With the upturn, opportunities for palm oil will return. The Malaysian Ministry of Plantation Industries and Commodities projects additional exports of 300,000 tonnes of processed palm oil to the Balkans via Turkey, which is geographically well placed to serve as a re-export hub.

Uthaya Kumar

Regional Director

MPOC Brussels

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Markets No Comments

Sub-Saharan Africa, with more than 40 countries and a population exceeding 1 billion, has become a substantial market for palm oil over the last 10 years. However, domestic palm oil production has been insufficient to meet the region’s needs.

In 2019, African countries produced about 2.8 million tonnes of palm oil, but demand stood at about 7.3 million tonnes. Imports therefore play an important role, already having recorded a compound annual growth rate of about 6% between 2010 and 2019 (Figure 1).

The use of Malaysian palm oil has kept pace with the region’s import volume. From 1.3 million tonnes in 2010, Malaysia’s contribution went up to a record high of 2.4 million tonnes in 2017. However, it then dipped slightly to 2.3 million tonnes in 2018 and to about 2 million tonnes in 2019 (Figure 2), due mainly to competition in a price-sensitive market.

West African countries provided about 2.8 million tonnes of palm oil in 2019. Nigeria was the biggest producer with 1.2 million tonnes. The Ivory Coast was the only net exporter, with 510,000 tonnes of production and 282,000 tonnes of exports. Ghana and Cameroon are other suppliers from the region.

The bulk of the palm oil imported from Malaysia and Indonesia by countries like Benin and Togo is rerouted to adjacent west African countries due to the favourable tax structure. Similarly, imports by Kenya and Mozambique are sent on to neighbouring landlocked countries in east and southern Africa.

The region’s refining industry has expanded rapidly over the last 10 years in tandem with changes in consumer choices and better economic conditions. Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya and Mozambique all have a large refining capacity now. In 2011, CPO/CPL constituted merely 3.8% of palm oil products imported from Malaysia. In recent years, CPO/CPL imports have grown to more than 40% of the total volume.

Tanzania, once a major importer of CPO, switched to RBD palm olein after the government increased the import duty on CPO from 10% to 25%, in response to pressure from domestic oilseeds producers. Countries like Benin, Togo, Angola and South Africa also prefer RBD palm olein. The region’s demand for specially-packed cooking oil fell from a high of 483,000 tonnes in 2011 to just 107,000 tonnes in 2019.

Bolstering trade

The Malaysian palm oil industry has much to gain by enhancing policy and business strategies, in order to make further inroads into Sub-Saharan Africa. The region’s palm oil market is growing rapidly, driven by rising consumption of processed food and fast food, among other changes. Viewing its countries as places of opportunity for collaboration would bring about mutual benefit. Two main strategies hold out possibilities.

Through the years, free trade agreements (FTA) have grown in importance and scope worldwide. These do not just reduce and eliminate tariffs, they also help address barriers that would otherwise impede the flow of goods and services. In addition, they encourage investment and facilitate market access.

However, Malaysia has yet to sign a FTA with any African country and, therefore, faces impediments by way of tariff barriers. To change this, Malaysia would not have to negotiate for lower tariffs with each country. It could negotiate with a bloc such as the African Continental Free Trade Area. This would streamline the process and unlock business opportunities more quickly than through negotiations with individual countries.

Despite Malaysia’s long presence in Africa, many in the oils and fats business are relatively unaware of investment opportunities, because of lack of information. In 2011, with investments of US$19 billion. Malaysia was Africa’s most important Asian investor, ahead of China and India in terms of the size of its foreign direct investment.

Currently, though, Malaysia lags behind investors from Indonesia and Singapore. Malaysian palm oil traders need to consider setting up joint ventures and partnerships to improve their market share.

They could also consider investing in storage, bulking and manufacturing facilities in the region to facilitate the production and distribution of Malaysian palm oil. The restaurant and café sectors are other segments that could yield high returns from the use of palm oil. Such ventures would help accelerate the local economy through new jobs and higher purchasing power, and boost demand for Malaysian palm oil.

Iskahar Nordin,

Marketing Executive,

Marketing & Market Development, MPOC

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Cover Story No Comments

The crude palm oil (CPO) price rally since June 2020 has been driven by supply disruptions in key edible oils, as well as in palm oil producing regions. With demand outpacing supply, the Bursa Malaysia Derivatives Exchange’s third-month benchmark price passed RM3,000 to trade at RM3,064 per tonne by mid-October. This was 38% higher from a year ago. On Nov 13, it hit its highest level, reaching RM3,490 per tonne.

Palm oil output from Indonesia and Malaysia was adversely affected by drought and reduced fertiliser application in 2019. This was compounded by labour shortage and movement restrictions due to the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. Indonesia and Malaysia produce about 85% of the global palm oil supply. The lower-than-expected supply of other edible oils, particularly sunflower and rapeseed oils, had induced the sharp rise in vegetable oil prices, which then had a spillover effect onto CPO prices.

Although the Covid-related partial lockdowns imposed in many countries had curbed demand for edible oils, the reduction in palm oil exports was short-lived. By the second quarter of 2020, key importing countries had started to re-stock. Also, reduced availability of used cooking oil and animal fats due to the pandemic has led some biodiesel producers to switch their feedstocks to vegetable oils, which also boosted global demand for palm oil.

At the Virtual Palm and Lauric Oils Price Outlook Conference & Exhibition in October, most analysts concurred that CPO prices would likely trade above RM2,500-3,000 per tonne for the rest of the year. This is due to tight palm oil stocks, concerns over the La Niña impact on edible oil supplies, and labour constraints in Malaysia which will impact fresh fruit bunch (FFB) yields in the coming months.

The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) is of the view that palm oil prices are likely to stay high in the first half of 2021, amid lower soybean crushing in Argentina and rising sunflower oil prices. Another key factor to watch is the weather pattern and the severity of La Niña going forward. Ongoing La Niña heavy rainfall has started to disrupt output in Southeast Asian palm oil producing countries. This will subdue global supply until the first quarter of 2021. Towards the second half of 2021, adequate rainfall and better crop management incentivised by the current high palm prices will significantly boost production.

Oil World recently forecast that vegetable oil prices in 2021 should trade higher due to improved demand and a tighter supply of soft oils such as soybean and sunflower oils. It indicated that soybean oil would lead the way. The rally in sunflower oil due to a lower crop harvest has also made soybean oil and palm oil attractive to price-sensitive buyers. China’s edible oils re-stocking policy is expected to continue in the months ahead with fund buying. Combined with Argentina’s soybean crushing problems, this could further boost palm oil prices.

Market outlook

Covid-19 pandemic

This is unlikely to have any severe impact on vegetable oil demand, including palm oil. This is because edible oils are a daily necessity, as a kitchen staple, cleaning agent or renewable fuel, in many people’s lives throughout the world.

In fact, the rising demand for oleochemical products has sustained demand for edible oils, including palm oil. Oleochemical derivatives such as glycerine, fatty acids and methyl ester, are the raw material for sanitisers, detergents and soaps which are experiencing rising demand due to better hygiene awareness and government-mandated health protocols.

Since the start of the pandemic, there has been a shift from business-to-business channels to business-to-consumer consumption habits with many households cooking and eating at home. The benefit of this change is that consumers will be changing their vegetable oils more regularly, as companies are selling smaller packs to consumers in the light of lower demand from restaurants.

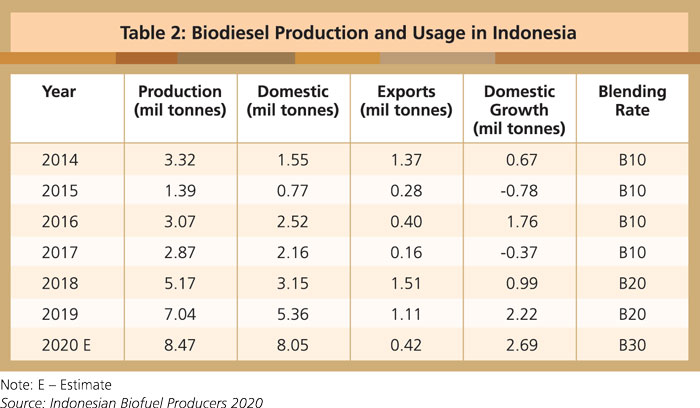

Biodiesel mandate

The Indonesian B30 mandate will help absorb the increase in palm oil supply in 2021. The wide gap between biodiesel and diesel prices has led to the accelerated drawdown of the Indonesian CPO fund. The earlier concerns about Indonesian biodiesel usage that might contract in 2020 will not happen, as the B30 biodiesel mandate will be fully implemented until the end of 2020.

However, the spread of palm oil to gas oil and low diesel price translates into expensive biodiesel mandates. As such, any revision or abandonment of biodiesel mandates would exert downward pressure on prices. In this context, it is crucial for both main producing countries to implement the biodiesel mandate, which is B30 for Indonesia and B20 for Malaysia. The use of palm oil biodiesel in the European Union could slow down if the supply of used cooking oil returns to the market with more economic activities opening up in 2021.

La Niña

The price outlook for 2021 will depend on the development of La Niña and its impact on the soybean complex in South America. Should there be a severe La Niña event, there will be lower soybean production. This, combined with a limited supply of sunflower and rapeseed oils from the Black Sea region, will result in higher vegetable oil prices in the first half of 2021. In this scenario, CPO prices will also benefit.

It is also noted that soybean crop replanting in Brazil and Argentina has been delayed due to the current dry weather conditions. If this persists, soybean yields in the coming season will be impacted. If the La Niña conditions advance into April 2021, this may also hurt soybean plantings in the US.

Oil palm replanting

The CPOPC sees structural changes in the global palm oil supply from 2021 due to a slowdown in new oil palm plantings throughout Indonesia and Malaysia since 2015. With the ageing tree profile across both countries, the replanting programme will also temporarily limit palm oil supply in the short to medium term.

As agricultural land becomes limited, oil palm replanting will be key to boosting palm oil yield across Indonesia and Malaysia. It is important to replant so as to sustain supply in the long run. Replanting is especially important for smallholders because their trees respectively account for 42% and 40% of Indonesian and Malaysian oil palm plantations.

Production outlook

There are three key drivers to the palm oil supply and growth prospects in 2021 – area expansion; oil palm tree age and yield; and weather.

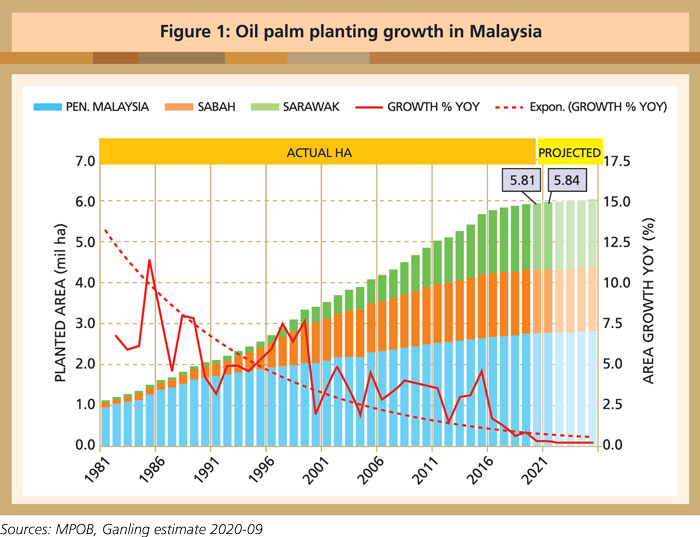

A recent Rabobank Group report highlighted that the slowdown in new plantings is due to a moratorium by the Indonesian and Malaysian governments on agricultural expansion and low commodity prices. Malaysia has capped its oil palm planted area at 6.5 million ha. To date, Indonesia has limited agricultural land availability and approved concession areas of up to 4 million ha. This structural change will impact the global palm oil supply from 2021. The replanting of 500,000 ha of oil palm by Indonesian smallholders, by the end of 2022, should sustain palm oil supply for the world.

According to Ganling Malaysia, the ongoing declining palm oil yield is due to ageing trees across Indonesia (24%) and Malaysia (30%). Any catch-up in replanting will temporarily limit the supply growth in the short to medium term. In Indonesia, replanting at an average of 1% per annum will take about 1.5 million tonnes out of the supply chain, while in Malaysia, the replanting rate average at 1.8% per annum is expected to withdraw about 1.1 million tonnes. The total withdrawal will be about 2.6 million tonnes out of the potential supply chain in 2021.

The La Niña weather pattern, which induces higher rainfall throughout tropical Indonesia and Malaysia, should boost fruit yield and CPO output in 2021. However, higher rainfall could also lead to flooding, which could hurt output and support prices.

The Meteorological, Climatological and Geophysical Agency of Indonesia has forecast a low-to-moderate intensity La Niña in the last three months of 2020. The agency expects about 55% of Indonesia to receive higher rainfall than average. Generally, Southeast Asia, South Africa, India and Australia receive above-normal rainfall due to La Niña, while Argentina, Europe, Brazil and the southern US experience drier weather. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has also stated that there is a 75% chance that La Niña will stay for the entire winter, into early 2021.

La Niña is likely to result in a drier climate in the Eastern Pacific and South America, a major area for soybean production. Soybean yields could drop in Argentina and Brazil due to drought-like conditions, which will then support soybean oil prices. Since palm oil and soybean oil are the two most consumed vegetable oils globally, their prices are positively correlated due to easy substitution.

Due to the movement control measures amid the Covid-19 pandemic, Malaysia has banned foreign workers from entering the country. Since foreign labour accounts for 75% of Malaysia’s oil palm plantation workforce, the shortage of workers will lead to palm oil production setbacks in crop losses. A prolonged labour shortage is expected to trigger a larger-than-expected drop in CPO output this year and in 2021.

Indonesia has also enforced large-scale social distancing measures to curb Covid-19. While plantations have imposed strict hygiene measures and restricted workers’ movement, supply disruption is expected to be limited as palm oil producers have no plans to halt operations.

Demand outlook

In 2021, palm oil imports by key destinations are expected to improve slightly from 2020, with the exception of Europe, according to Refinitiv Agriculture Research, Singapore. Economic activities in key palm oil destinations are recovering more swiftly than anticipated, thanks to the resumption of business activities and financial stimuli. Palm oil demand from India and China is expected to grow in 2021.

India’s palm oil imports are expected to spike by 4.8% to 8.7 million tonnes, boosted by a gradual recovery in demand, as well as low inventories. There will be re-stocking and higher demand from bulk buyers in the hotel/restaurant/café sectors after slower demand during the Covid-19 lockdowns. While there has been a surge in palm oil exports to India, domestic crop cultivation, especially soybean, appears to have risen too. Therefore, if there are very good harvests of the rapeseed, groundnut and soybean crops in 2021, India could curtail its palm oil purchases.

China’s demand for palm oil is anticipated to edge up by 3% to 6.9 million tonnes in 2021. The market has seen strong demand for palm oil in anticipation of the Chinese New Year celebrations that typically fall in January or February, as well as due to re-stocking.

EU palm oil imports will likely decline by 8.6% to 6.4 million tonnes, partly due to its policies. Palm oil biodiesel (considered as ‘high risk’ for indirect land-use change under the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive II) usage will be gradually reduced from 2023 until 2030.

Moreover, the EU has set new food safety standards on 3-MCPDE and GE, contaminants found in refined oil products, potentially affecting palm oil demand in the food sector. As the Covid-19 pandemic leads to widespread restaurant closures and lower biodiesel use, overall consumption of palm oil is expected to be reduced in Europe.

Refinitiv also reports that Indonesia and Malaysia have continued to support the B30 and B20 biodiesel programmes respectively, despite subdued biodiesel consumption during the pandemic resulting from social distancing measures and movement control orders, as well as the high CPO premium over gas oil.

The price spread between palm oil and gas oil has been widening since the last quarter of 2019 to the peak of US$400 per tonne level. But in September 2020, it stabilised at around US$370, the highest since April 2016.

Due to the CPO premium over gas oil, the Indonesian government has allocated 2.78 trillion Rupiah to support the B30 programme for 2020.

Malaysia’s B20 mandate was restarted in Sarawak on Sept 1, 2020. It will be implemented in Sabah and Peninsular Malaysia in January and June 2021 respectively. Biodiesel mandates are anticipated to absorb around 10 million tonnes of CPO from both palm oil producing countries in 2021. This will support domestic consumption and reduce palm oil inventories.

It is projected that the palm oil market will likely trend up in the near-term in tandem with soybean prices, which is mainly supported by higher demand for soybean from China; lower global soybean stock estimates by the US Department of Agriculture; and unfavourable weather in the US Midwest and South America (namely Argentina and Brazil). One example would be Brazil’s current drought, which has delayed soybean plantings, thereby supporting soybean prices. La Niña could also limit the soybean oil yield potential.

Price and supply outlook

As at November 2020, palm oil futures on Bursa Malaysia Derivatives Market were trading above RM3,000 per tonne. If this continues for the rest of the year, palm oil prices will probably average around RM2,600-2,650, a return to the more optimistic prices of 2017.

Based on tighter supply-demand dynamics and low palm oil stocks, the CPOPC sees the momentum continuing until higher production resumes in the second half of 2021. The wider CPO price discount to other vegetable oils is also supportive of global palm oil demand. Droughts in the Black Sea region are also limiting sunflower and rapeseed production. This will result in elevated vegetable oil prices well into the first half of 2021. At the same time, the developing La Niña may cause some disruptions to soybean production in South America. If the dry weather persists, there will be more severe soybean oil disruptions in Brazil and Argentina.

Current edible oil stockpiles in China and India are also tight, keeping edible oil imports healthy. The price surge in the last quarter of 2020 reflects the rapidly recovering demand from India and China, the world’s two biggest palm oil consumers after they went through nationwide lockdowns and temporary halts on economic activities due to Covid-19. The rise in competing edible oil prices is also positive. It could encourage consumers to switch to palm oil as a cheaper alternative.

Many analysts agree that palm oil supply will improve in the second half of 2021 due to the effect of higher rainfall, which should be beneficial for FFB yields. Both Ganling Malaysia and Rabobank foresee that good weather conditions in Indonesia and Malaysia will raise global palm oil supply by 3.1 million tonnes in 2021.

There are also concerns that the current zero export tax for CPO in Malaysia may not be extended beyond Dec 31, 2020. This could negatively impact CPO exports to India, while Indonesia could raise its CPO export levy to support its B30 mandate.

On the whole, the palm oil outlook in 2021 looks favourable compared with the average prices of 2019 and 2020. However, this will depend on the development of La Niña on the soybean complex in South America and Indonesia’s B30 biodiesel mandate. The full implementation of the B30 mandate in Indonesia and the B20 mandate in Malaysia is crucial to sustain domestic consumption and absorb the anticipated palm oil supply growth. A deficit situation in global vegetable oils will lend support to CPO prices in 2021.

Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries

Jakarta, Indonesia

This is a slightly edited version of the report published in December 2020.

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Publication No Comments

The Libuk Durian massacre was certainly the bloodiest event in the early history of Tungud. However the saddest incident, which took place the following year, must surely be the story of Suppiah and Leena.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Planter's Diary, Issue 4 - 2020 No Comments

Leslie Davidson, Tungud Estate’s startup Manager, wondered whether a birthday party should be held to mark the first year of development of Sabah’s commercial oil palm estate. He sounded out his friend Tom Prentice, Chairman of Harrisons and Crosfield, Sabah’s premier trading company.

From 1925 to 1955 Harrisons had been the sole owner of every forest tree in the territory – Cinderella’s resources which had never seen the light of day outside Sabah. The London shareholders possibly had no idea they owned such bounty.

A hardworking product of Edinburgh’s public schools, Tom had been appointed chairman of the company’s 10 branches in Sarawak, Brunei and Sabah. He was charged by his London office to further the development of its agencies, which included Straits Steamships and British Overseas Airways; the universally-popular Lister engines; Carrier air-conditioners, and endless items of construction materials, paint, industrial chemicals and even bathroom furniture, all made in Britain.

Sabah, on the other hand, had been devastated by General MacArthur’s softening-up raids before the American forces retook it from Japanese invaders. Its wooden shoplots and houses had been destroyed by bombing; and there was no commercial deep-sea port, veneer mill, plywood mill, timber drying plant or a Forest Department timber laboratory.

But its timber business had begun to thaw out of its ice age by demands from the cause of all the trouble – Japan and its former colony, Korea. The thaw started with a 1955 government decision to break Harrisons’s timber monopoly. Nine new licences were issued and exports permitted for the first time of round timber logs. This was no concern of Unilever’s and certainly not of Leslie’s.

From his year-old attap-and-kajang Labuk riverside quarters Leslie understood that a birthday party might be worth the effort, provided that at least two other interested parties could be shown that oil palm could be grown on former tobacco plantation or rubber land – and accommodate the British government’s demand to “grow more food for Britain”. But what would be Leslie’s sales pitch?

On Unilever’s arrival, Tom had offered to act as their managing agent; every plantation company throughout the Far East with head offices in London – except one – used agency houses to manage their investments. The use of local expertise made good sense. The agent for Unilever’s oil palm in Johore was the Guthrie Corporation.

Harrisons’ investments in Borneo included its branch offices distributed along the coastal towns of the three territories; an expanding domestic timber business and 400 ha of high-quality rubber in Sandakan. Leslie declined Tom’s invitation with thanks, despite their similar backgrounds, the one from Aberdeen, the other from Edinburgh.

But what about other unknowns? Throughout Borneo, oil palm had by 1960 just reached preliminary evaluation – the nearest precedents were the modest 24,000 ha in Malaya compared with 2 million ha of rubber. Where now in Sabah was land available for oil palm?

Due to the lack of roads to the interior, any new sites would be confined to the coastline. Mosytn Estate’s experimental oil palm planting on medium rainfall, fertile volcanic soils was served by its own deep-water port in Kunak, 30km from the plantation. It had been in use since 1920; requiring only a tank farm.

Tungud’s lands, although flat and swampy, had been farmed between 1895 and 1918 by The New London Tobacco Company. What was good for tobacco, a notoriously fickle crop, was very likely good for oil palm, as extensively demonstrated by Dutch planters in Sumatra’s coastal provinces.

How to move palm oil from Tungud to Sandakan? Leslie’s preliminary notes had mentioned dracones; giant rubber tubes of palm oil pulled by ocean-going tug from the plantation to the bulking installation; the very mention of which drew giggles from Unilever’s head office staff.

How to store palm oil until ready for shipment? Unilever offered to carry out the works for the Public Works Department. Its director, stretching to his fullest height, snorted: “Leslie, kindly put in a bid alongside other consultants; we’ll soon find out who knows what they’re talking about.”

How to ship palm oil from Sandakan when the harbour bar depth was a mere 7 metres at low tide? The Sandakan ships’ pilot advised dredging an extra 5 metres in depth, which would allow a tanker draught of 10 metres. All the dredged material could reclaim a site for a bulking installation.

Future of Sabah

For the anniversary festivities, Leslie proposed a badminton match – while learning the plantation business at Kluang he had represented Johore at badminton – followed by a satay party at the riverside community centre in Tungud. This was the fish and vegetable market by day and badminton court by night, weather permitting.

The guests arrived at the Tungud jetty by afternoon. The potential investors included Tom, whose Malayan branch owned two oil palm plantations and a brand-new research station at Banting; and River Estates’ Datuk Guy Barrett.

The popular and gregarious Beluran District Officer, Tan Sri OKK Mohammed Yassin (‘Miyasin’) joined the party after hearing his court cases for the day. On arrival, he announced that he was about to go to Britain on study leave to cram up on colonial law and legal English. Within a few years, he became Sabah’s Yang Di-Pertua Negara.

Leslie took us on a tour of the first-year clearing. Standing in the back of the tractor and trailer, he showed us the oil palm nursery, the first village site, an obvious airstrip site and the proposed factory site.

The evening was warm but remained dry. The ‘birthday special’ badminton match was exciting. Leslie had been invited to challenge Tungud’s reigning singles champion, the Bugis excavator driver Mohammadia Lanto. Leslie was well fired-up with a powerful attacking game and a forehand smash. He was earning points with apparent ease when it became clear that Mohammadia was playing a waiting game, content to return every backline lob while awaiting a slowdown of Leslie’s footwork. Mohammadia was clearly very fit.

Both players drew breath for hot satay. Leslie’s former amah Juriah, now my cook, looked after the charcoal grill. Play then resumed inconclusively for another 15 minutes. Leslie could see spectator interest waning and after his service, called it a day. It had been an exciting sparring match. “To be resumed,” the players agreed.

Now we discovered why Leslie had convened the party. He asked: “How many more birthday parties will we see? Just how long will it be before Sabah is granted Independence, I wonder?”

It was an innocent enough question that day. No hint of any discussion had reached the newspapers about Independence for the three Borneo territories – Sabah, Brunei and Sarawak – save that Donald Stephens had dropped an editorial hint in his North Borneo Times. He wondered whether ‘Merdeka’ was the real reason for Malaya’s recently speeded-up pace of development.

Leslie took the bull by the horns, asking Tom: “How much longer before Independence?” Tom had clearly given the matter no thought, but not about to be caught napping, airily replied: “Twenty years!”

Leslie then looked at Barrett; who with a flash of his shy smile, ventured “Twelve years!”

In turn, Miyasin said: “Well, the British government has thought about it as I mentioned when I arrived, even if the Malayan government has not. I have just received my marching orders. Nobody seems to have any idea, but good luck to whatever may happen!”

Leslie and I had recently been subject to the winds of change in west Africa and had discussed the problem in passing; we had both privately concluded without a shred of evidence: “Four or five years.”

As newcomers, we were not expected to air our views. In the event we were proved hopelessly out of touch. Tungud Estate saw out exactly two more birthdays and one month before Sabah was handed over to Malaysia.

Tungud Estate, or rather Pamol (Sabah) Sdn Bhd as it had become, remained Malaysia’s last colonial plantation company with the sole exception of Perak’s United Plantations Bhd. Even the almost 100-year tenure of Harrisons and Crosfield was taken over – almost a management buyout – by Malaysian interests.

Moray K Graham

Retired Planter

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Sustainability No Comments

Three leading companies in the palm oil industry – Kao Corporation, Apical Group and Asian Agri – have launched a sustainability initiative to help independent oil palm smallholders in Indonesia to improve yields, acquire international certification and eventually secure sales premiums from selling certified palm oil.

Known as the ‘SMallholder Inclusion for better Livelihood & Empowerment’ programme – or SMILE – the collaboration is between downstream producer Kao Corporation, mid-stream processor, exporter and trader Apical Group, and upstream producer Asian Agri. The 11-year initiative seeks to continue building a more sustainable palm oil value chain by working with independent smallholders, who contribute more than 28% to Indonesia’s palm oil market.

The collaboration recognises that independent smallholders are private business owners who are challenged to increase their yield and productivity, but may not have the knowledge or the technical expertise to do so.

Global production of palm oil stands at 75 million tonnes per year and is expected to grow to 111.3 million tonnes by 2025. There is now a greater focus in Indonesia on improving palm oil productivity while minimising the need to extend agricultural land. This not only helps to safeguard food security, but serves to balance social, environmental and economic needs.

Kao Corporation, Apical Group and Asian Agri are implementing activities in accordance with the framework provided by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), and working to ensure traceability as far as the plantation, in order to build an environmentally-friendly, socially-aware supply chain.

While the palm oil industry has moved forward with national certification schemes such as Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil or multi-stakeholder led collaborations like the RSPO, certification for independent smallholders has only recently gained momentum.

SMILE seeks to bridge the knowledge gap of independent smallholders by partnering with them and leveraging on the success that companies such as Asian Agri have demonstrated with its long-time partnerships with smallholders.

Implementing the programme

SMILE will assemble a team of experts with extensive experience in the areas of plantation management and agronomy to work with 5,000 independent smallholders that manage approximately 18,000 ha of plantations in the provinces of North Sumatra, Riau and Jambi. Through customised seminars and workshops, the team will:

This upscaling and provision of equipment will be implemented from 2020-30 with a view to helping independent smallholders secure RSPO certifications by 2030. Once certified, they will be eligible to receive certified palm oil premiums averaging 5% higher than non-certified palm oil.

As part of RSPO requirements as well as the companies’ commitment to help the community collectively realise the UN Sustainable Development Goals, SMILE includes initiatives that promote greater inclusion and improved livelihoods via empowerment initiatives for communities. The goal to improve the livelihood of independent smallholders will be through enhanced productivity with ‘no deforestation, no peat land and no exploitation’.

Throughout implementation, the three companies will regularly engage various stakeholders such as NGOs, non-profit organisations and community leaders. This is to ensure competent delivery of training, adequate allocation of equipment, and timely provision of needs at the estate and community levels. It will also optimise collaboration toward building a more sustainable and traceable supply chain.

Under the SMILE programme, Kao plans to provide farmers with its functional agrochemical adjuvant – which helps to boost productivity while also reducing the burden on the environment – along with technical guidance on how to use the product effectively.

It is also collaborating with NGOs and local non-profit organisations to implement surveys and analysis of the effectiveness of the support being provided with regard to boosting productivity and improving the smallholders’ working environment.

Apical Group is one of the largest exporters of palm oil in Indonesia, owning and controlling an extensive spectrum of the palm oil business value chain from sourcing to distribution. It also engages in the refining, processing and trading of palm oil for both domestic use and international export.

The Group promotes the protection of high conservation value and high carbon stock areas. Since 2017, it has been a partner of Tropical Forest Alliance 2020, a global public-private partnership that brings together governments, the private sector and civil society organisations to reduce deforestation associated with the sourcing of commodities such as palm oil, beef, soybean and pulp and paper.

Asian Agri is one of Indonesia’s largest palm oil producers. A pioneer of the Trans-National Government Migration programme, it currently works with 30,000 Plasma Scheme smallholders in Riau and Jambi who operate 60,000 ha of oil palm plantations, and independent smallholders who manage a total of 41,000 ha.

It has implemented a strict ‘no burn’ policy since 1994 as well as best practices in sustainable plantation management. Asian Agri has helped its smallholder partners improve productivity, yield and supply chain traceability, while assisting them to obtain certification.

Apical Group

Jakarta, Indonesia

This is an edited version of a press release issued on Oct 15, 2020.

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Sustainability No Comments

Malaysia will be among 192 countries participating in Expo 2020 Dubai, now rescheduled to run from Oct 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022. Themed ‘Connecting Minds, Creating the Future’, the event is the first to be held in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia regions.

The achievements of the forestry sector will be the shining example of Malaysia’s theme ‘Energising Sustainability’. Its pavilion will depict the country’s seriousness and commitment to climate change mitigation and forest conservation.

Malaysia will engage with other countries, businesses and the anticipated 25 million visitors in exploring innovative ideas and initiatives to assist its endeavours as the leading tropical country in conserving forests for the shared prosperity of humankind.

The Malaysian pavilion is self-built and depicts a Rainforest Canopy. Its theme showcases the nation’s commitment and approaches to sustainable development. It is the first pavilion to adopt the net zero carbon approach.

Activities will include permanent displays, pocket talks, summits and forums, cultural performances, demos and 26 weekly thematic business programmes. The business weeks will be helmed and supported by 22 ministries, 40 agencies and five state governments.

Malaysia’s participation is led by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, with the Malaysian Green Technology and Climate Change Centre (MGTC) as the implementing agency.

The MGTC was formerly known as the Malaysian Green Technology Corporation or GreenTech Malaysia. It is a government agency under the purview of the Ministry of Environment and Water, mandated to lead the nation in the areas of green growth, climate change mitigation and climate resilience and adaptation.

The role of carbon-absorbing forests especially tropical rainforests in regulating climate has never been more important. Once again, protecting the remaining forested areas in developing countries has regained international attention and has been thrust into the forefront of the battle to reverse climate change.

Forest land accounts for about 31% of the world’s land surface area of 4.1 billion ha, with the largest proportion (45%), in the tropical domain. Of this, the oldest biome located close to the equator and found within the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn – the rainforests of Amazon, Congo Basin and Southeast Asia – is touted to be the game-changing carbon sink of the world.

Forest-related emissions due to land-use change and unsustainable logging practices contribute about one-fifth of all global emissions. Therefore, protecting these remaining sinks would give humankind the fighting chance to reverse the course of runaway climate change.

Their importance has gained substantial traction as countries intensify negotiations to enhance international cooperation to combat climate change following the implementation of the first phase of the Kyoto Protocol (2008-12); under this, developed countries will reduce 5% of their emissions from the 1990 level.

The role of forests as both emission sources and carbon reservoirs has been acknowledged and addressed, namely with the mechanism known as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in developing countries (REDD-plus). This was adopted in 2007 at the 13th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Bali, Indonesia.

The ‘plus’, which refers to the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks, is significant for many developing countries where deforestation rates are relatively small. This means that such countries would be compensated for having kept their forests as the lungs of the world; hence REDD-plus would be an effective policy approach to preventing deforestation.

Decades of disinformation

Contrary to decades of disinformation that Malaysia has a ‘high deforestation rate’, one indisputable fact stands out. More than 50% of the country’s landmass is still covered by forests after 63 years of post-Independence nation-building.

How did a country that relied heavily on its primary resources – an economic activity carried over from the colonial period – maintain so much of its forest area amidst population growth, infrastructure demands and pressure to extract more timber? The answer lies in the appreciation for sustainable development.

The watershed year was 1992. The venue was Rio de Janeiro, a city in Brazil where a global meeting of the UN Conference on Environment and Development agreed that environmental protection and economic development are not necessarily mutually exclusive. And that developing countries must not be forced to give up their right to a better standard of living in the name of environmental protection. It was accepted that achieving sustainable development requires balancing the three pillars – economic, environmental and social – of modern society.

Malaysia was a vocal advocate for the rights to development, to industrialise, to eradicate poverty and to prosper. This legitimate desire to become a developed nation would inevitably mean some forested areas would have to give way for economic transformation.

Yet, the government made the bold pledge of maintaining at least 50% (16.5 million ha) of its relatively small landmass as forest. To date, no country has promised to set aside half of its territory as a contribution to global well-being. As at 2018, approximately 55.3% of the land area was still under forest. The pledge at the Earth Summit in Rio has indeed become Malaysia’s generous gift to the world.

Despite the challenges, scepticism and doubts, Malaysia remains steadfast in upholding its pledge. One item of disinformation has been the suspicion that Malaysia counts its oil palm and rubber plantations as part of the 50% forest cover – this claim has posed a considerable challenge to its palm oil industry

It must be clarified that, in the country’s reporting to the Food and Agriculture Organisation – the UN agency tasked with monitoring the world’s forestry resources – rubber and oil palm plantations have never been included in the statistics. What has been counted as forests are dipterocarp forests, montane forests, and freshwater, peat and mangrove swamp forests.

In addition, as a signatory to the UNFCCC and its supplementary treaties – the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement – Malaysia is building on the Earth Summit pledge by protecting vital carbon sinks.

Sustainable forest management

Malaysia has since adopted the world-renowned Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) practices and subjected its timber harvesting supply chain practices to third-party certification. These efforts have minimised the negative impacts of timber harvesting in the production forests and protected its carbon stock.

Management of specific ecological functions of forests has also been enhanced through the establishment of totally protected areas as well as protective status for soil conservation and water catchment within the permanent reserve forests system. Soil protection not only preserves the fertility of soil and prevents run-off and sedimentation as part of flood mitigation, it also prevents the release of soil carbon.

Following the anti-tropical timber campaign in the late 1980s and early 1990s that resulted in the demand for traceability of timber products, Malaysia embraced voluntary timber certification with the establishment of the Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme (MTCS). Governed by the Malaysian Timber Certification Council, it is both a national commitment towards ensuring SFM and a market-linked tool to reform forestry practices.

The MTCS has gradually gained global recognition. In 2009, it became the first tropical timber certification scheme in the Asia Pacific region to be endorsed by the Netherlands’ Programme for Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), the largest forest certification programme representing more than 300 million ha of certified forests worldwide.

Operational since 2001, the MTCS has generated 2.2 million m³ of certified timber and timber products exported to 69 destinations as at 2019. To date, more than five million ha of forests in Malaysia have been certified under the MTCS and Forest Stewardship Council Scheme (FSC). The Deramakot Forest Reserve in the state of Sabah became the world’s first tropical rainforest to be certified by the FSC in 1997.

Tracing of timber from the forests to the end products is assured by the Chain of Custody (CoC) certification process; 381 timber companies have received PEFC CoC certificates, out of some 3,500 such companies in Malaysia.

The total area of certified forests under the MTCS represents 13% of the world’s certified tropical forests, a remarkable achievement for a small developing country. In fact, under the National Policy on Biological Diversity (2016-25), the country has set a target of 100% of all timber and timber products to be sustainably managed.

All this is testimony to Malaysia’s seriousness in implementing SFM and contributing to the world trade in sustainable timber and timber products, thus ensuring that its logging industry is a positive force in terms of global forestry governance and living up to the challenge of sustainable development.

It also puts the country in good stead to fulfil its commitment not only to the Paris Agreement but also the Convention on Biological Diversity and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

Ts. Shamsul Bahar Mohd Nor

CEO, MGTC &

Project Director, Malaysia Pavilion for Expo 2020 Dubai

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Markets No Comments

On 15 November 2020, following eight years of negotiations and countless delays, 15 countries in the Asia-Pacific region signed the world’s biggest trade agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement. The RCEP Agreement is an ASEAN-led free trade agreement (hereinafter, FTA), grouping the ten ASEAN Member States (i.e., Brunei-Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam), and the five regional countries with which ASEAN already has free trade agreements, namely Australia, China, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand (i.e., the so-called ASEAN+1 FTA partners, minus India).

The RCEP Agreement has the potential to transform the region into an integrated market of about 2.27 billion people (i.e., 30% of the world’s population), a combined GDP of USD 26.2 trillion (i.e., 30% of global the gross domestic product (GDP), and nearly 28% of global trade. The RCEP will open up opportunities for businesses, providing greater market access across all areas of trade – goods, services, and investments. The signing of the RCEP signals a strong commitment to keep markets open, to ensure supply chain connectivity in the Asia-Pacific region, and to provide much-needed support and optimism for job creation and economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic.

The RCEP builds on ASEAN’s bilateral FTAs with its key trading partners

The RCEP negotiations were launched in November 2012 by the ten ASEAN Member States and the six regional countries with which ASEAN already has free trade agreements with the intention of strengthening the regional economic architecture. In November 2019, India withdrew from the RCEP negotiations, noting that its key issues and concerns were not being adequately addressed. Nevertheless, RCEP Parties kept the door open for India through the Ministers’ Declaration on India’s Participation in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which acknowledges the strategic importance of India’s participation to establish stronger economic linkages and connectivity for the benefit of all people in the region and further development of the global economy. Notably, the RCEP links together China, Japan and Korea, which are Asia’s first, second, and fourth-largest economies, respectively, providing the push and momentum to finally conclude the stalled China-Japan-Korea FTA talks.

Comprising 20 chapters, with a total of 17 annexes and 54 market access schedules, the RCEP Agreement is a modern and comprehensive FTA covering commitments in the areas of trade in goods, trade in services, investment, dispute settlement, and economic and technical cooperation. Importantly, the RCEP Agreement goes beyond the existing agreements concluded by the ASEAN Member States with Australia, China, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand (hereinafter, ASEAN+1 FTAs) and includes commitments on electronic commerce, intellectual property, Government procurement, competition, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The RCEP Agreement intends to provide new trade and investment opportunities for businesses.

The RCEP Agreement provides important benefits to traders in the Asia-Pacific region

Studies indicate that the RCEP Agreement could boost global trade by USD 500 billion in the next ten years. However, this requires that businesses do take advantage of the new commitments by the Parties, once the RCEP is ratified and starts being implemented.

The RCEP Agreement aims at ensuring transparent and predictable trade rules. More specifically, the RCEP Agreement reaffirms the Parties’ WTO commitments on the publication and notification of their trade regulations, which aims at addressing a key business concern, namely the lack of information on non-tariff measures (NTMs). Despite the transparency system not being as ambitious as that of the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA), Article 2.18 of the RCEP Agreement provides an innovative platform for Parties to conduct technical consultations on NTMs that adversely affect trade between them, establishing a timeframe within which the consultations should be resolved (i.e., 180 days from the request of technical consultations), which can be shortened due to the urgency of the matter or if the consultations concern perishable goods. Moreover, these discussions must be transparent and must provide any other RCEP Party the opportunity to join the consultations whenever they have an interest in doing so, subject to the consulting Parties’ consent.

Businesses will be able to benefit from substantial cost-savings under the RCEP, with the Parties committing to the gradual removal of Customs duties on about 92% of products over 20 years in accordance with each Party’s Schedule of Tariff Commitments (Annex I of the RCEP Agreement), while some tariff lines can be traded duty-free upon its entry into force. This will likely encourage businesses to source raw materials from other RCEP Parties, increasing foreign direct investments (FDI) into the region and fostering regional value chains.

Under the RCEP Agreement, the Parties negotiated exclusions for sensitive products from tariff reductions, particularly for agricultural products and other regulated goods. For instance, Indonesia has committed to eliminating tariffs on 91% of its tariff lines in the coming years, while the other 9% have been designated as sensitive products, which means that, inter alia, rice, weapons, and alcoholic beverages are not subject to the liberalisation commitments. Japan excluded its key agricultural products, namely rice, wheat, beef, pork, dairy, and sugar from liberalisation in order to protect domestic farmers from a potential influx of more competitive imports. More specifically, Japan will abolish tariffs on 56% of agricultural products imported from China, 49% of those from South Korea, and 61% of agricultural products from ASEAN Member States, as well as from Australia and New Zealand. Additionally, certain Parties will grant market access through tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) to other Parties. For instance, vis-à-vis China, Vietnam does not exclude any products from liberalisation, but has established a list of 30 products that will be subject to a lower (in quota) tariff-rate, but then subject to a higher tariff-rate once the respective quota is exceeded.

Unified rules of origin

Under the RCEP Agreement, businesses will benefit from preferential treatment under a unified set of rules and procedures when trading their products between and among RCEP Parties. Until now, diverging rules and procedures, particularly regarding origin criteria and certification procedures, under various FTAs in the region, had led to complex rules, which discouraged traders to take advantage of them. Most notably, the RCEP Agreement will provide for unified rules of origin where, essentially, the criteria to determine whether a product may benefit from preferential treatment under the agreement are the same for all RCEP Parties. Moreover, businesses will only need one origin certification document to cover all RCEP Parties, which should significantly expedite the processes of verifying origin qualification and documentation. The unified rules of origin under the RCEP are expected to facilitate supply-chain management, reduce transaction costs borne by businesses for trading with multiple countries in the wider region, as well as create a more stable environment for trade.

The chapter on electronic commerce

The RCEP Agreement contains a chapter on electronic commerce, an important innovation compared to the existing ASEAN+1 FTAs and the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA). While it may not be as sophisticated as the chapter on electronic commerce in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CP-TPP), which links Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam, it still contains important elements. The inclusion of this chapter aims at enhancing the regulatory environment for businesses trading digitally in the region and at supporting consumers’ confidence in online transactions. In essence, the chapter on electronic commerce sets out provisions that encourage the RCEP Parties to improve the administration and relevant processes for trade using electronic means. The chapter also requires Parties to adopt or maintain a legal framework that creates a conducive environment for the further development of electronic commerce, which is supposed to cover areas such as online consumer protection, online personal information protection, transparency, and paperless trading.

Pursuant to Article 12.2 of the RCEP Agreement, the Parties agree to refrain from imposing Customs duties on electronic transmissions, in line with the WTO’s moratorium on e-commerce. Additionally, Article 14.14 of the RCEP Agreement prohibits data localisation requirements, unless they are necessary to achieve a Party’s public policy objectives or to protect its security interests.

Next steps towards the effective implementation of the RCEP

After its signing, the Parties to the RCEP Agreement will commence their respective domestic processes to ratify the agreement. However, the RCEP Agreement will only enter into force once six of ten ASEAN Member States and three of the five other Parties have deposited their instruments of ratification, acceptance, or approval with the ASEAN Secretary-General. The RCEP Agreement is, therefore, not expected to come into effect before the end of 2021 or the beginning of 2022.

The increased economic opportunities will likely also increase competition in the region. During this ratification period, it is, therefore, critical for companies to prepare and strategically plan on how to leverage the trade preferences that the RCEP Agreement will deliver to reduce trade costs and gain competitive advantages in the RCEP Parties’ markets. Such assessment should include determining the tangible benefits of the RCEP Agreement vis-à-vis the existing ASEAN+1 FTAs, which will remain effective even as the RCEP enters into force, as well as reviewing their current supply chains to determine if there is an opportunity to expand into the region’s growing markets.

Maria Esperanza Alconcel, Ignacio Carreño, Fabrizio De Angelis, Simone Dioguardi, Tobias Dolle, Michelle Limenta, Alya Mahira, Lourdes Medina Perez and Paolo R. Vergano contributed to this issue.

27 November 2020 – Trade Perspectives© – FratiniVergano

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Markets No Comments

Despite increasing environmental concerns, European Union (EU) consumers still eat large amounts of meat and dairy products. Beef, pork and dairy production have significant implications for the environment in the EU and in third countries, notably in South America. Cattle farming and the cultivation of feed crops like soybean are big contributors to tropical deforestation, environmental degradation, methane emissions and pollution. Yet, this has been largely neglected by EU policy makers and the media, even as commodities like palm oil are scapegoated for alleged negative effect

Read more »By gofb-adm on Tuesday, December 29th, 2020 in Issue 4 - 2020, Markets No Comments

The Netherlands is of supreme importance to palm oil and its producers. It serves as a processing and redistribution hub, and is by far the largest importer of palm oil in Europe (Figure 1).

The Dutch economy is highly trade-oriented. Innovation, the geographical location, the Port of Rotterdam (Europe’s largest), good infrastructure, plus a well-trained, multilingual and highly productive workforce make up the country’s strengths.

Trade has driven the economic engine for centuries. However, due to a reliance on exports, the economy is highly susceptible to global booms and busts such as the current crisis brought about by the Covid-19 global pandemic. This has put an abrupt end to six years of uninterrupted expansion, including a rate of 1.8% in 2019. Analysts now predict the Dutch economy to contract by almost 7% in 2020.

A decline in Dutch exports is expected in 2020. This will be accompanied by falling imports due to reduced domestic demand by both consumers and the export industry, which uses imports as preliminary products. Imports will decline by more than 10%, according to forecasts by the European Commission. A recovery is likely to begin only in 2021.

Backing sustainability

The Netherlands benefits significantly from its trade in palm oil. Consequently, its voice of opposition to palm oil is much weaker than, say, in France which produces most of the EU’s rapeseed – a direct competitor to palm oil.

In late 2019, the European Union (EU) adopted legislation to effectively phase out palm oil as a component of biofuels by 2030, under the revised Renewable Energy Directive. In February 2020, Biofuels Digest posted a report headlined ‘Netherlands adamantly against EU ban on palm oil even when it’s sustainable’. This can be described as the country’s official attitude. The Dutch government outlines its reasons for using palm oil on the website Netherlandsandyou.nl (Figure 2).

Against this backdrop, the Dutch government supports the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) standard through the National Initiatives for Sustainable Climate Smart Oil Palm Smallholders (NI-SCOPS). The Initiative also works in Nigeria, Ghana and Indonesia. The goal in Malaysia is to increase the share of certified sustainable independent smallholders (Figure 3).

The commitment to sustainable palm oil in the Netherlands goes beyond political lip-service. Unilever, a Dutch-British multinational company and one of the world’s three largest consumer goods producers, is banking on sustainable palm oil as well.

On Aug 19, 2020, Food Ingredients reported that Unilever is using satellite data, geolocation, the blockchain and artificial intelligence to make its supply chain fully transparent. To that end, the company is teaming up with the Rainforest Alliance and using the PalmTrace platform of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. The goal is to find out the origin of fresh fruit bunches supplied to palm oil mills.

Are such investments worth the effort? More and more stakeholders think so. Sustainable palm oil, with its versatility and superior productivity, is just too precious a commodity to be banned. Switching to the use of sustainable palm oil production is not a short-term proposition. But the awareness is growing that it will ultimately protect sales and margins in the European market.

In the words of Marc Engel, Chief Supply Chain Officer at Unilever: “Better monitoring helps all of us to understand what’s happening within our supply chains. By companies coming together and using cutting-edge technology to carefully monitor our forests, we can all get closer to achieving our collective goal of ending deforestation.”

Malaysia’s path toward mandatory certification has not been easy. A substantial amount of resources has been expended on the process, and more will be needed. Despite initial scepticism, the progress in certified land area has been impressive. Independent smallholder certification remains challenging, but efforts like NI-SCOPS will help change that.

Governments like that of the Netherlands are beginning to recognise what has been achieved in Malaysia. In February 2020, building on a previous agreement between the Dutch and the Malaysian governments, the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB), IDH – The Sustainable Trade Initiative, and Solidaridad signed a Memorandum of Understanding in the Netherlands. It is a further step towards a sustainable palm oil supply chain into Europe.

Such developments make it plain that, with the MSPO, Malaysia has hit the nail on the head. It is right to take this path because certified sustainable palm oil is what European customers want. Without it, the future for palm oil in the EU would be bleak.

Palm oil in numbers

In 2019, five producer countries, led by Indonesia and Malaysia, jointly accounted for 90% of Dutch palm oil imports (Figure 4). Compared to 2015, the volume exported by Papua New Guinea, Colombia and Honduras has grown – Papua New Guinea and Honduras by factor 7.2 and 3.4 respectively, while Colombia’s share has almost doubled.

The Netherlands imported about 35% more palm oil in 2019 compared to 2015 (Figure 5).

In 2019, Malaysia was the largest supplier of palm kernel oil to the Netherlands for the fifth consecutive year (Figure 6). However, Papua New Guinea is catching up fast. Also, with Guatemala – which could triple its share – a new player has arrived in this market.

Palm kernel imports grew by around 30% between 2015 and 2019 (Figure 7).

The dominance of Indonesian palm kernel meal is striking. Malaysia’s share of imports has dropped since 2017. In 2019, Germany exported more of the product than Malaysia to the Netherlands (Figure 8).

Dutch imports of palm kernel meal went up by 20% between 2015 and 2019 (Figure 9).

The Netherlands re-exports some 40% of palm oil imports, with more than half going to the three EU buyers (Figure 10).

The MPOB registered 670,207 tonnes of palm oil exports to the Netherlands from January to July 2020. This was an increase of more than 32% over the corresponding period in 2019. The year 2020 could have marked a milestone for sustainable palm oil, but this has been derailed by Covid-19.

However, if Malaysia pursues its sustainability goals through the MSPO and succeeds in convincing buyers that its palm oil is the sustainable choice, it will not be long before the benefits are reaped.

MPOC Brussels