Royal Reality Check for Oil Palm Growers

By gofb-adm on Friday, September 27th, 2019 in Issue 3 -2019, Cover Story No Comments

By gofb-adm on Friday, September 27th, 2019 in Issue 3 -2019, Cover Story No Comments

Duli Yang Maha Mulia Paduka Seri Sultan of Perak Darul Ridzuan, Sultan Nazrin Muizzuddin Shah ibni Almarhum Sultan Azlan Muhibbuddin Shah Al-Maghfur-Lah, graced the opening of the 9th International Planters’ Conference of the Incorporated Society of Planters (ISP) on July 15 in Kuala Lumpur.

In the Royal Address, he urged the oil palm industry to remain focused on innovation, productivity and sustainability in rising to meet challenges. The conference, themed ‘Plantation Industry: Charting the Future – Transforming People, Policies, Processes’, also marked the ISP’s centenary as a registered body and its contributions to Malaysia’s plantation sector.

“I am very pleased to be here to open this event, and would like to congratulate the ISP on the occasion of its centenary. This conference, the ninth that has been put on by the Society, promises two days of thought-provoking insights and lively debate from the many distinguished speakers, senior industry figures, numerous planters and interested observers. All of you are gathered here to discuss the future of the important plantation sector, and to consider the transformations that it may need to undergo to meet the challenges of the future.

While the members of the ISP plant a range of crops, among them, the oil palm is by far the most valuable to the country in economic terms, contributing significantly in taxes, export earnings and employment. At the same time, the sector has been subject to considerable criticism for some time over the negative environmental impacts of the large-scale forest conversion that is associated with its expansion, through carbon emissions and biodiversity loss.

Commendable progress on sustainability has been made as a result of this attention, however unwelcome it may be. Further efforts are still required, however. This is necessary not just to respond to external criticism or market restrictions, but is imperative in itself. This is in order to limit any further contribution from deforestation to the global environmental emergency that we are collectively facing, the urgency of which is now increasingly being recognised. So an effective strategy for resolving this issue must lie right at the heart of any process of charting the future course of the sector.

Further progress on sustainability will also rest on efforts to boost productivity in the sector, through the application of new technologies and other innovations. Achieving greater efficiency in food production more broadly – beyond only palm oil – is a critical element of responding to the global environmental crisis. This will, of course, itself create major additional challenges from rising temperatures, reduced availability of water, depleted soils and many others. The development of effective means to address these wider sustainability and environmental challenges must thus also be put at the centre of the discussions taking place here on the future of the sector.

I want to focus my remarks today on how the palm oil sector can meet these challenges, through advances in productivity and efficiency, as well as by further limiting its negative impacts. This is likely to require far-reaching changes, but these may now be inevitable anyway, given the challenges that are faced. Business as usual cannot continue any longer.1 However, the potential returns to this transformation – in both environmental and economic terms – should more than adequately compensate for the risks that must now be taken.

Over the past few decades, palm oil has become a major global crop, and a key element of the global food system. This system already contributes disproportionately to the global environmental crisis, and predicted population growth will only make this worse.2 In order to feed the ever-rising population – expected to reach around 9,8 billion by 2050 – ever-growing production of meat and other proteins, of staple grains and of vegetable oils will be required. While consumption of all foods will increase in absolute terms, that of preferred proteins and oils will rise even faster as more people are able to afford them.

From an economic perspective, this growth in the demand for food, including palm oil, may seem to present an exciting opportunity. But without significant changes to the current system, the environmental consequences will be dire. These include rising emissions of methane from livestock, and of carbon from land-use change for expanding agricultural production and from transportation. They also include further damage to soil and water ecosystems from pesticide, herbicide and fertiliser use, and continued biodiversity loss of animals, insects and plants.

More sustainable ways to meet the growing global demand for food must clearly be developed. This will entail the more intensive and less-damaging use of existing resources, as well as greater efficiency in all areas of production, distribution and consumption. Just as in other sectors, new technologies and other innovations will play a key role in driving these changes in the agricultural sector. This transformation, to echo the theme of the conference, will be led by people, who will develop the processes and policies that will drive the sector forward successfully in this challenging context.

So what are the implications for the palm oil sector? As many of us here are well aware, oil palm is already far more sustainable than many other crops in various ways. With an average yield per hectare of eight times that of soybean and four times that of rapeseed, oil palm is the most land-efficient vegetable oil by some margin.3 Its production also requires far less pesticide than other vegetable oils, while fertiliser application is reduced by the widespread use of mulching. And considerable efforts have been made in the sector to limit deforestation and carbon emissions. Primary and secondary rainforests are now being better protected, and development on peat is being eliminated altogether.

These actions go well beyond those being taken in some other sectors, something that reflects the relatively early development of certification schemes in this sector. Despite some deficiencies, these mechanisms have contributed to the reduction of negative environmental impacts; the dissemination of best agricultural practices such as mulching; and to the implementation of more social safeguards as well.

These certification schemes continue to evolve, with the principles and criteria of the RSPO further strengthened through their recent review, and membership of the MSPO now becoming compulsory. Once its more limited requirements have been fully implemented, companies and smallholders alike will be better prepared to move towards the more stringent RSPO requirements. Sufficient support, especially for smallholders, will help to facilitate this process. It is also vital to make sure that these mechanisms really do work in practice to regulate the sector effectively, in order to ensure its accountability.

Although the sector is thus making good progress towards greater sustainability through these means, more can and must be done. This includes boosting productivity through the application of new technologies and other innovations. This approach holds much promise in economic as well as environmental terms – whether from genetic breakthroughs; the discovery of new processing methods or uses; or the achievement of greater efficiency in existing production and distribution processes.

Innovation and technology have, of course, played a key role in the extraordinary rise of the oil palm. From being a minor tropical tree crop only a few short decades ago, it has become a globally significant crop, used in everything from processed food to personal care products to biofuel, quite apart from as a cooking oil. Much of this growth has occurred since the early 1980s, with the development of oil palm tissue culture techniques, and the successful introduction of the pollinating weevil to Southeast Asia from its natural home in West Africa. History records very few successful introductions of this kind – consider the disaster caused by importing cane toads into Australia or, closer to home, the unfortunate introduction of crows to Klang over a century ago. This exceptional case of the weevil resulted in substantial savings compared to the cost of artificial pollination.

Other characteristics of palm oil and palm kernel oil have also contributed to the rise of the sector, including their saturated fat content and heat resistance. These qualities have facilitated the use of the two oils in the manufacture of a wide range of food and other products. This expansion of the commercial applications of the crop has been driven by advances in bio-technology and bio-chemistry, with a key role played by fractionation processes. The very ubiquity of palm oil that is so lamented by its critics in fact reflects the ingenuity and dedication of the Malaysian and other scientists who have led this process of invention.

Although investment in research and development has continued, there have been far fewer breakthroughs in recent years. Yields have been more or less stagnant for decades. The considerable efforts being put into the development of genetic characteristics to facilitate harvesting, such as slower growth for example, have yet to come to fruition. Recent advances in genetic engineering do hold great potential for this area, however. The gene-editing technique CRISPR is already being successfully applied to other crops, such as the creation of genetically-decaffeinated coffee.

Even in the absence of any major leap forward, there are many other sources of improved productivity that can be tapped within existing technological boundaries. The potential can be seen in the large gap between the average yield of around 20 breeders, of 35 or even 40 tonnes. More attention should be given to the question of how these much higher yields can be achieved throughout the sector. Smallholders will again require particular attention and support.

Further improvements in estate management practices can help to boost productivity, and therefore sustainability, as can higher extraction rates. The use of only the best quality and non-contaminated planting materials is another crucial element, and again something that must be applied throughout the sector. This alone can make such a difference to yield, that early replanting to improve the overall tree stock may even justified. The early replacement of rubber trees with higher-yielding varieties – both during the colonial period and following the end of the Second World War – paid off quickly. The certification schemes can contribute to the dissemination and the implementation of these best practices.

Boosting productivity will also require a more efficient balance to be achieved between labour and machinery usage. As well as relative costs, this must take into account the ongoing hiring constraints, and address the losses of as much as 10-20% of production that are caused each year by labour shortages. Mechanisation has its own challenges, of course, with motorised harvesting cutters not workable in all terrains, for example, or beyond a certain height. This is again despite the considerable efforts that have been made to improve these tools.

These factors have contributed to the continued reliance on existing technologies, with refining and milling processes both unchanged for decades.4 The reasons for this apparent resistance to change, as well as the very real constraints that are faced, should be further explored, along with the policy implications. A more favourable regulatory environment could help to encourage a bolder approach. This could include simplified patenting procedures, or tax incentives for piloting new technologies.5

The relatively slow pace of change may reflect a broader trend in the agricultural sector. Apart from a few exceptions, the application of the recent wave of technological advances associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution is significantly lagging in this sector. One study found that the number of entrepreneurs developing agricultural businesses based on cutting-edge technologies is just one-twentieth of those in the healthcare sector and with only one-tenth of the investment.6

There are some exciting developments in agriculture, however. These include the use of sensors and the Internet of Things to achieve far greater precision in the application of chemicals. Along with the use of drones for delivery, this promises to have a revolutionary impact on the efficiency of chemical usage. This is good news for the environment and for the bottom line. But more and bolder innovation in the sector – with institutional support where necessary to overcome market failures – is clearly needed.

Recent advances in the area of remote sensing do have the potential to have a transformative impact in the palm oil sector. The growing use of UDAR mapping is enabling a far more precise understanding to be developed of the landscape than in the past.7 This contributes to more efficient planning and operation of plantations and any associated protected areas. At the same time, the more widespread availability of ‘last generation’ satellite imagery is enabling far more accurate monitoring of land-use change than was possible previously. This allows responsible companies to demonstrate clearly compliance with their no-deforestation commitments, while ‘rogue’ companies can more easily be identified and shamed.

Rather than respond defensively to critics, representatives and supporters of the oil palm sector should instead reach out and provide the much more nuanced account of its sustainability record and practices that is, in fact, the case. This should emphasise the progress that has already been made by the sector towards limiting negative impacts, and the continued and strengthened efforts. It should also focus on the importance of boosting further the productivity, and therefore sustainability, of what is already a leading crop in this regard.

The potential contribution of technological advance to both these aspects of sustainability is amply illustrated by the example of remote sensing technologies, which strengthen environmental monitoring and boost efficiency. Other new technologies will prove equally transformative, and innovation in the sector should be encouraged and supported as much as possible, in order to exploit the full potential of the current wave of technological advance. Innovative approaches will also be necessary to meet the growing environmental challenges that will likely be faced.

Ultimately, it will be you, the people in the sector, who will play the central role in driving the changes to policies and processes that will be required as the palm oil and plantation sectors chart their course into an uncertain future. As you embark on this difficult journey, I urge you to make innovation and sustainability your twin goals. It is very encouraging in this regard to see that increased attention is being given to sustainability issues in the agenda and concerns of this and other conferences. On this note, I now declare the conference open.”

The Royal Address is reproduced with kind permission of the ISP.

1 Chandran, M.R., ‘Malaysian Palm Oil Industry: Business as Usual… Not an Option Anymore’, 14th ISP National Seminar, July 2018

2 ‘World Economic Porum and McKinsey (January 2018) ‘Innovation with a Purpose: The role of technology innovation in accelerating food systems transformation’

3 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325999702 Oil palm and biodiversity a situation analysis by the IUCN Oil Palm Task force

4 Chandran, ibid

5 Chandran, ibid.

6 WEF and McKinsey, ibid.

7 LiDAR or ‘light detection and ranging’, is an aerial surveying method that uses pulsed laser light to measure distance to a target, with the results mapped digitally in 3D

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019 in Issue 3 -2019, Special Report No Comments

Sir Jonathan Porritt

Founder Director, Forum for the Future

The oil palm industry in Southeast Asia has found itself under constant pressure over the last 15 years from environmental and development non-governmental organisations (NGOs), based predominantly in Europe and the US. Opinions vary as to the effectiveness of that campaigning pressure, but few would deny that the industry has significantly transformed both its policies and its practices to reduce its environmental and social impacts on the ground. There is a clear case to be made that it has moved further and faster than other globally-traded commodities during the same period of time, and many question why those other industries have not been exposed to the same intensity of campaigning – on deforestation and land use issues, in particular.

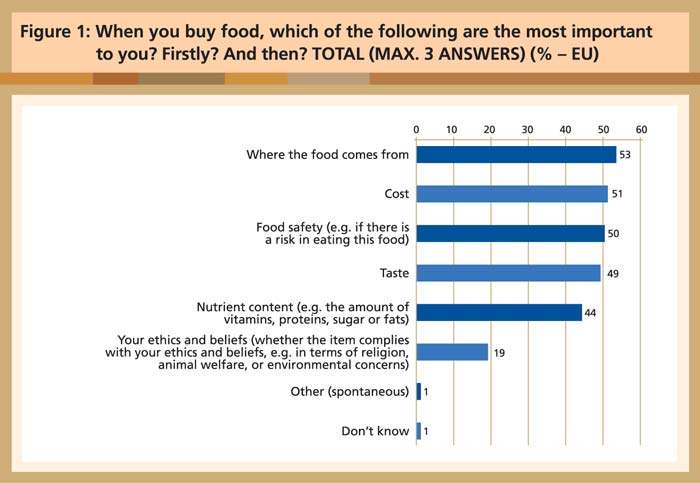

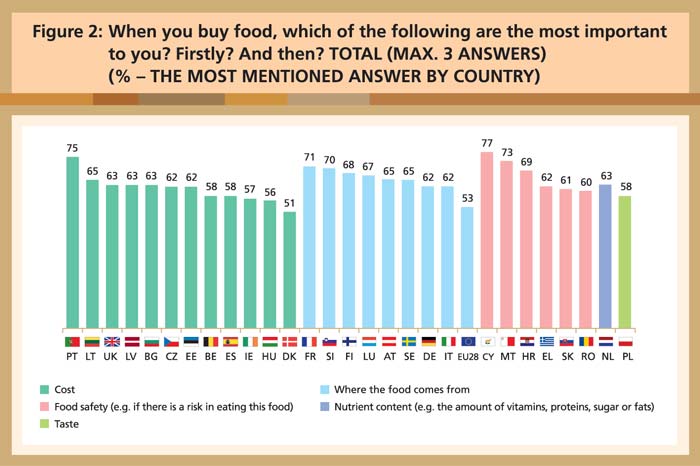

Growers in Southeast Asia and elsewhere are angry and mystified; consumers in Europe and the US (largely ignorant as they are of the critically important contribution the oil palm industry makes to both GDP and the lives of millions of people in Southeast Asia) are confused and easily persuaded that adopting a ‘No palm oil’ position is the most ‘responsible’ way forward. Building on the revised Principles & Criteria from the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, the author will explore opportunities for reconciling some of today’s seemingly intractable confrontations.

This Keynote Lecture was presented at the 9th International Planters Conference of the Incorporated Society of Planters held in July in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Back in 2012, I was invited by Sime Darby Bhd to contribute to its Prestigious Lecture Series. I was honoured and intrigued, though more than a little ignorant about the oil palm industry at that time. It was certainly not my intention to spend the next seven years of my life becoming more preoccupied with this sector of the global economy than any other! I’m significantly less ignorant than I was, but still learning.

It has been an extraordinary privilege, and it remains a privilege to act as the Independent Sustainability Advisor to the Board of Sime Darby Plantation Bhd. My passion in life is sustainable development. Not the environment per se, but the interplay between the environment, the economy, society, individual responsibility, and what it is that allows all of us to make sense of our brief span of time on this beautiful planet of ours.

When the Brundtland Report – ‘Our Common Future’ (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987) – came out, I had already been actively involved for more than a decade in advocating for more sustainable ways of creating wealth. But the definition of sustainable development that it advanced at the time (‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’) has provided a useful hook ever since. Not least because it obliges all of us to think about what is known as ‘intergenerational justice’ – what is it that one generation owes all those generations to come, in terms of the legacy we leave them?

And the oil palm industry is undoubtedly one of those sectors where the practice of sustainable development (rather than the theory) has had to be pioneered and worked through in enormous detail. In September 2015, the UN General Assembly signed off on a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to be delivered by 2030. Of the 17 Goals, 10 are directly relevant to the industry:

| Goal 1: | End poverty in all its forms everywhere. |

| Goal 2: | End hunger, achieve food security and improve nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture. |

| Goal 3: | Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. |

| Goal 8: | Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all. |

| Goal 9: | Build resilient infrastructure, promote sustainable industrialisation, and foster innovation. |

| Goal 10: | Reduce inequality within and among countries. |

| Goal 12: | Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. |

| Goal 13: | Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. |

| Goal 15: | Sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, halt biodiversity loss. |

| Goal 17: | Revitalise partnerships for sustainable development. |

Embracing the SDGs means taking an integrated view, seeking to optimise outcomes across all the goals rather than cherry-picking any one particular goal at the expense of others – a point to which I will return later.

It’s also true to say that no other large-scale agricultural commodity has had to take such full account of its impacts (economic, social and environmental), or to improve its overall performance so significantly in order to meet the demands of its principal customers around the world. Many involved in the industry itself see this as disproportionate scrutiny, and often ask why it is that many of their competitors (other vegetable oils, and particularly the soybean industry) merit so much less attention. On the other hand, campaigners see the focus on the industry as entirely appropriate, given the level of tropical deforestation (impacting both on climate change and concerns about biodiversity) for which it has been held responsible historically – and, to a lesser degree, currently.

The last year has provided us with the most compelling evidence as to the importance of those campaigns. In October last year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its ‘Global Warming of 1.5ºC Report’, powerfully reminding governments that although the difference between an average temperature increase of no more than 1.5ºC by the end of the century, rather than 2ºC, may not sound particularly significant, the consequences of going to the higher rather than the lower figure will be very grave indeed – for the whole of humankind – in terms of the increase in extreme weather events, impacts on food production, rising sea levels and so on.

Since then, more detailed reports from both the Arctic and the Antarctic have revealed that the melting of the ice, at both ends of the world, is gathering pace at a rate that scientists find hard to believe. The implications for rising sea levels in this century are beyond grave.

And it’s been much the same story in terms of our gathering realisation of the damage we’ve done to the web of life on which we still entirely depend. In September last year, WWF International published its biennial Living Planet Report, with the still shocking headline that 60% of the populations of all vertebrates have been lost since 1970.

Further reports have highlighted impacts on other species, perhaps most disturbingly on populations of insects all around the world. A major study in February – ‘Worldwide Decline of the Entomofauna: A Review of its Drivers’ (Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys, 2019) – highlighted just how comprehensive and extensive the damage has been over the last 30 years, with 40% of all insect species now in rapid decline. Without insects, food webs collapse and ecosystem services fail, threatening the existence of all other species. Understandably, some have described this as ‘an insect apocalypse’.

There will be few industries more aware of the importance of pollinating insects than this one, transformed as it was by the introduction from West Africa of the pollinating weevil, Elaeidobius kamerunicus, in 1981.

Accelerating climate change and devastating biodiversity loss are two sides of the same coin. And we have left it so late that we now find ourselves in an out-and-out emergency on both counts. Awareness of this is now growing, with the powerful advocacy of superstars like David Attenborough influencing more and more people. But levels of indifference or outright ignorance remain disturbingly high.

That is true, I’m afraid, even here in Malaysia. One of the unfortunate consequences of the oil palm industry finding itself under such concerted attack for its contribution to deforestation was a defensive instinct, along the way, to disparage the science of climate change. There are still significant pockets of ‘denialism’ within the industry, intent on arguing that climate change is predominantly a natural rather than a man-made phenomenon, or that it’s nothing like as serious as mainstream scientists now recognise it to be – almost unanimously. This has been deeply unhelpful in terms of enabling the industry to thrive indefinitely into the future without any further impacts on Malaysia’s forests or peatlands, and it would greatly enhance the reputation of the industry today were it to develop a definitive position of its own on both the science and the accelerating impacts of climate change.

I would argue that this body of scientific work has to be our starting-point in any debate about the future of the oil palm industry. It tells us that we have no more than 10-15 years to do what we need to do to avoid the threat of runaway climate change. And part of the answer to that emergency is to stop clearing any more mature forest – and, indeed, to plant as much new forest as can possibly be achieved.

But I am not an absolutist when it comes to interpreting what that means in practice. For instance, I do not believe that the language associated with ‘zero deforestation’ has been particularly helpful in terms of changing behaviour on the ground. As Co-Chair of the High Carbon Stock Science Study, generously supported by Sime Darby Plantation and by many companies represented here today, (which published its Final Report in December 2015), I was keen to help people understand the important difference between ‘zero deforestation’ and ‘zero net emissions’ from land use change – or ‘no net loss’.

The Report from the Study’s Technical Committee concluded:

‘Experience over the last 20 years has taught us that no amount of high-level declarations will protect forests on the ground unless and until local people and communities can see their own economic interests and historic entitlements are better met through forests being set aside and protected for the long term, rather than cut down for short-term gain.’ (Raison et al., 2015)

It must also be clear to everyone involved in this debate that the only way to protect the world’s remaining rainforests is for relevant nation states (or regional/provincial jurisdictions) to legislate for such an outcome. However good their intentions may be, voluntary ‘no deforestation’ commitments signed up to by progressive non-state actors, from both the private sector and civil society, will only ever have a limited impact.

Progress on the part of consumer goods companies in the West has been particularly disappointing. In May this year, a report from WWF and the Zoological Society of London revealed that almost one in five RSPO Members had failed to submit proper progress reports to the RSPO, including many consumer goods manufacturers and retailers.

In March, the Global Canopy’s ‘Forest 500’ Report assessed the progress of 350 leading companies against their commitments to ensure deforestation-free supply chains, made either through the Consumer Goods Forum or the New York Declaration on Forests: ‘The most powerful companies in forest-risk supply chains do not appear to be implementing the commitments they have set to meet global deforestation targets. With just one year left to the 2020 deadline, it is clearer than ever that even companies with strong commitments will not be able to assert that their supply chains are deforestation-free by that deadline.’

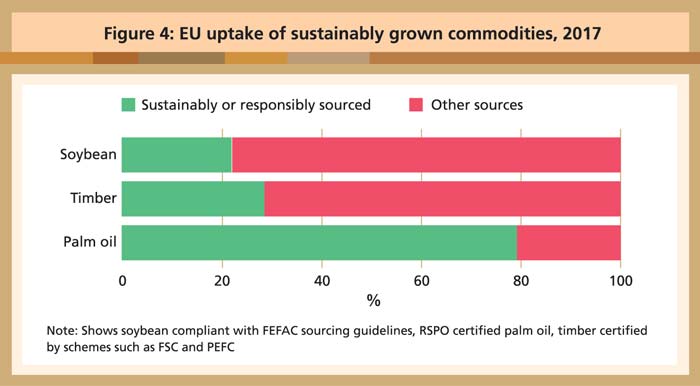

Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (CSPO) accounts for about 19% of global palm oil production, but no more than 50% of this volume is actually sold as CSPO. This continuing hypocrisy on the part of so many Western companies (in effect, continuing to put ‘cheap’ before ‘sustainable’) is, in my opinion, entirely reprehensible.

Without unambiguous legislative foundations, and a determination to enforce whatever regulations are put in place, it’s difficult to see how the oil palm industry will ever be free of the kind of controversies that have flared up so frequently over the last decade or so. That’s why the current positioning of the Malaysian Government is so critical.

There are, of course, longer-term threats to the future of the industry that no government will be able to do much about. Back in 2016, I visited a huge bio-refinery in Brazil, using that country’s abundant sugar cane as feedstock to fatten up genetically modified microorganisms to produce oils identical in every way to ‘natural’ vegetable oils – apart, that is, from their price! But how long will it be before biotechnologists manage to crack that problem of high costs as well?

And then there are all the risks associated with accelerating climate change, which are already having a marked impact on the industry, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Each company in the industry should be assessing its portfolio of landholdings to determine high-risk assets, developing mitigation strategies (through improved agronomy, more efficient irrigation and so on), and ensuring that it is not left with ‘stranded assets’ on its books.

There will be many other climate-induced changes. Within the next 15 years, the European car market will have been fundamentally transformed, with the internal combustion engine progressively ousted by hybrids and pureplay electric vehicles. Demand for diesel in Europe is already steadily declining, year on year, primarily on account of concerns about air pollution – because of the highly damaging impact that particulates from diesel are having on human health, but also because of climate change. The decline of diesel vehicles is unstoppable – just look at Norway as the trailblazer here, with 30% of all new car sales in 2018 already electric vehicles. The implications of this transformation have not been adequately thought through here in Malaysia, as the industry fights like fury to maintain access to the EU biodiesel market – a market that is going to be a great deal smaller in 2030 than you may imagine.

This shift cannot be dismissed as gesture politics on the part of rich European countries. Earlier in the year, the province of Hainan in China (with a population of nine million) announced that Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles will no longer be sold, as of next year, with a view to eliminating all ICEs in the province by 2030. At the same time, it is rapidly installing one of the most comprehensive charging infrastructures for Electric Vehicles anywhere in the world.

Lack of proportionality

In the medium term, however, the prospects for palm oil are good, not just because of the many inherent qualities of palm oil (which will be very well known to all of you!), but because demand for palm oil and its derivatives is still growing, particularly in China and India. Few analysts believe that this trend is likely to abate anytime soon. That’s the market reality, and it makes little sense for anti-palm oil campaigners to seek to wave it away as if it was of no importance.

One of the most important elements in our High Carbon Stock Science Study was to remind stakeholders in Europe and elsewhere that any serious sustainability analysis must take into consideration all vegetable oils, not just palm oil. In terms of tonnes of oil produced per hectare, oil palm produces around 3.5 tonnes in comparison to soybean oil at around 0.5 tonnes, sunflower oil at 0.6 tonnes and canola at 0.75 tonnes. In other words, oil palm productivity is seven times that of soybean, six times that of sunflower, and five times that of rapeseed. As one of the principal contributors to our Science Study, Dr James Fry (cited by Raison et al., 2015), pointed out at the time:

‘If any lost palm output was to be made up solely from extra soybean, the soybean area would have to rise from 111 million ha in 2013 to 232 million ha in 2025. If canola fills the breach, its area would have to rise from 36 to 109 million ha. For sunflower, the area would have to rise from 26 to 87 million ha.’

These comparisons are insufficiently recognised by European politicians, let alone by most European citizens. It is deeply irritating having to listen to those politicians justifying their dependence on scientifically-flawed Indirect Land Use Change (ILUC) assessments (to determine whether or not an oil should be judged high risk or low risk) whilst completely ignoring another kind of ILUC – the Indirect Land Use Consequences of any wholesale substitution of one oil for another. The consequences for Brazil’s already severely damaged Cerrado, in trying to develop an additional 121 million ha of soybean by 2025, would be utterly devastating. In those circumstances, even the European Commission (EC) might acknowledge, from the point of view of eliminating deforestation, that the risks associated with soybean are as high if not higher than those associated with palm oil.

As land becomes more and more scare, and competition for access to that land becomes ever fiercer, it’s clearly a priority to meet that growing demand for vegetable oils as efficiently as possible, with the lowest possible emissions of greenhouse gases, using as little land as is necessary. Suppress the use of palm oil in favour of its significantly less efficient competitors, and the indirect sustainability impacts will, I believe, turn out to be much worse than the impacts of sourcing that palm oil in a genuinely sustainable way.

That is why WWF International, for instance, has been very clear about the undesirable consequences of boycotts or outright bans: ‘Boycotts of palm oil will neither protect nor restore the rainforest, where companies undertaking actions for a more sustainable palm oil industry are contributing to a long-lasting and transparent solution.’ (Chan, 2018) And it’s why the World Alliance of Zoos and Aquariums has been so progressive and smart in choosing to educate visitors to many of its zoos regarding the difference between sustainable and unsustainable palm oil, rather than opting for the easier line of outright condemnation.

These unambiguous positions compare very favourably with the inconsistent and deliberately opaque positioning of Greenpeace and other Western NGOs.

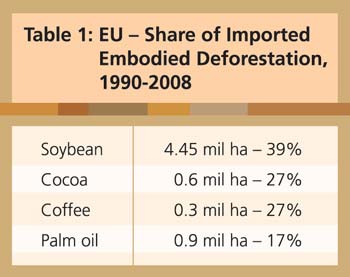

The lack of proportionality and factual accuracy in dealing with these issues remains surprising. It doesn’t matter how many times one repeats it, but calculations as to relative causes of continuing deforestation are rarely included in the debate about palm oil. As you know, production of beef, soybean, palm oil and forestry products account for the largest share of tropical deforestation (around 27%), with beef production the biggest single driver of deforestation in every Amazon country, accounting for around 80% of current deforestation rates in Brazil. Soybean cultivation is the second major driver of deforestation in the Amazon basin – at a scale that dwarfs continuing deforestation for palm oil in Southeast Asia. These realities are almost entirely unknown to the vast majority of European citizens.

In April, Global Forest Watch released its data for tree cover loss in 2018. (Tree cover loss is not the same as deforestation, as it includes areas lost to fire, disease and other natural disturbances, as well as timber harvesting and oil palm replanting operations.) At 440,000 ha (which includes 144,000 ha of primary forest tree cover), total tree cover loss in Malaysia in 2018 was around 15% lower than the average over the previous 10 years (Global Forest Watch, 2019).

And it doesn’t matter how many times one points out that the threat to the orang utan in Southeast Asia is not quite as horrendous as implied in stock campaigning materials.

But let us be clear here: that figure is still far too high, and one which campaigners are right to continue to highlight. Just as they’re right to expect producers to meet all their obligations through RSPO certification, to manage their supply chains more rigorously, to eliminate all bad actors from those supply chains, and so on. That, it seems to me, is precisely what responsible, effective campaigning NGOs should be doing.

But at some point in the last few years, an honourable record of campaigning to improve the industry’s performance (however uncomfortable that may have been to many in the industry itself) spilled over into what I call ‘the generic demonisation’ of palm oil per se. It was no longer a problem caused by ‘bad actors’ in the industry, but of the product itself. The decision last year by the UK retailer Iceland to remove all palm oil from its own-brand products was based on the judgement of its CEO, Richard Walker, that it was not possible to distinguish between CSPO and uncertified oil. Not to put too fine a point on it, as I pointed out at the time, that is an example either of startling ignorance or wilful mendacity.

Since then, the iconic London store, Selfridges, has gone down the same route, a highly regrettable decision in my opinion. But these examples are but the tip of the iceberg regarding the use of ‘palm oil free’ labels becoming all too common in many European countries.

Greenpeace’s hugely successful film, ‘Rang-tan: the story of dirty palm oil’, unapologetically endorsed that same view, blatantly manipulating children’s (and adults’) emotions through the representation of a baby orang utan, making no effort whatsoever to distinguish between certified sustainable and uncertified oil.

Just as worryingly, the decision earlier in the year on the part of Norway’s pension fund to de-list all the remaining palm oil companies in its portfolio was a further manifestation of generic demonisation. How the Trustees of the Fund suppose that this will serve the interests of their beneficiaries I do not know – though it certainly secures an easier life for those Trustees. Blanket condemnation is always so much easier than exercising one’s critical faculties.

How can we account for this sorry state of affairs? For sure, campaigners in the West have become increasingly impatient with the degree to which the ‘bad actors’ in the industry have continued to act with impunity – or even ‘immunity’, given how reluctant politicians have been to put an end to their flagrant disregard for the environment, for climate change, for workers’ rights, local communities and indigenous people.

But that’s too easy an explanation. I spend endless hours reading press releases and reports from both Western NGOs and representatives of the Malaysian industry, and I am (perhaps naïvely) astonished at how little readiness there is to acknowledge any validity regarding the case made by those on the other side.

I would, for instance, be so delighted to hear a single European NGO acknowledge that much of the campaign against palm oil in Europe is driven by straightforward protectionism on the part of Europe’s very powerful vegetable oil trade associations – for canola and sunflower oil. How can it help consumers in Europe to come to a balanced view of this without bringing that incontrovertible reality to their attention, each and every time the debate is joined?

By contrast, why do we never hear from leaders in the industry in Southeast Asia that their constant efforts to protect and build markets in the West are inevitably undermined by those ‘bad actors’ in the industry? The current efforts being made by RSPO-certified companies to clean up their supply chains represents a de facto recognition of the damage done by those bad actors, but it’s never quite spelled out with the clarity that would be helpful in terms of influencing Western opinion.

(By the way, it’s worth pausing to acknowledge that those efforts – to clean up supply chains – are quite extraordinary. In the last two or three years, supply chain mapping has moved forward dramatically, as has risk assessment analysis, and we’re just beginning to see the fruits of that combined industry endeavour to manage these uniquely complex supply chains.)

But it goes deeper than that, as we all know. I’ve read the speeches by Malaysian Minister of Primary Industries Teresa Kok Suh Sim and Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad attacking the highly controversial decision by the EC (at the behest of uncompromising Green MEPs in the European Parliament) to phase out the import of palm oil for biodiesel in Europe. They (and their Indonesian counterparts) are basing their arguments on the case that the EU’s decision is not only directly contrary to WTO rules, but directly contrary to the EU’s support for the SDGs – highlighting in particular the impact the new measures will have on smallholders in both countries. It is indeed most regrettable that so many politicians in the EU choose to cherry-pick the SDGs in this way.

Although I am not convinced that seeking an all-out war with the EU is the most sensible way to proceed, I have a lot of sympathy for the case that is being made here. I have learned over the last few years that many Western NGOs and politicians have very little understanding of the socio-economic contribution of the oil palm industry to the economic success of both Malaysia and Indonesia, both historically and today. I cannot honestly recall a moment where these economic considerations have been taken into account as the arguments rage back and forth about deforestation and the plight of the orang utan.

As a result of which, I have come to the disconcerting conclusion that some Western NGOs are influenced, directly or indirectly, by a form of eco-colonialism. That is not a charge I lay lightly, but it is indisputably there in the way they think and act, and it is deeply problematic.

Significant shifts required

So let’s step back for a moment, given the need to reconcile two absolute imperatives: a market imperative that the world needs a secure supply of traceable CSPO; and the environmental imperative that the world needs a complete halt to any further clearance of primary or mature secondary forest, from both a climate change and a biodiversity point of view. How do you suppose historians will be reflecting on these issues from the vantage-point of, say, 2040 or 2050?

If things continue as they are, whatever the rights and wrongs of the current, ever more painful controversies, my sense is that they will be reflecting, first and foremost, on an unprecedented opportunity missed. An opportunity to reconcile the wholly legitimate interests of responsible palm oil producers, with the need to eliminate further deforestation, and to protect the rights of all those working in the industry, at every level.

But is it too late to seize hold of that opportunity? Here in Malaysia, I would like to suggest that it is not. Indeed, almost all of the elements required to make it possible are already in place, in varying degrees as discussed below:

1. The Malaysian Government is firmly committed to preventing further deforestation, to improving the level of protection for the 50% of its land that is still in natural forest, and putting an upper limit on the amount of land which will be dedicated to oil palm cultivation.

2. The Malaysian Government has set a target for all producers (including smallholders) to be certified to the MSPO standard by the end of this year. Whilst it is true that the MSPO is not as rigorous as the standard set by the RSPO, it is an internationally- approved standard which significantly raises the bar in terms of environmental and social safeguards. It would be an astonishing achievement for the industry to meet that target.

3. The state of Sabah is pursuing a strategy to ensure that all oil produced anywhere in the State should be CSPO. This would be the first of a number of ‘jurisdictional approaches’ that are currently being pursued in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

4. Leading Malaysian companies have reaffirmed their commitment to NDPE – no deforestation, no development on peat, and no exploitation. And, as I’ve already mentioned, a significant investment is being made in assessing the risk of deforestation in their supply chains, and in implementing appropriate management strategies to put an end to that deforestation.

5. There are a number of forward-looking NGOs (including Conservation International, WWF International and the World Resources Institute) that are fully cognisant of the critical socio-economic role the industry plays in Southeast Asia and, increasingly, in other countries in West Africa and South America. They are keen to help broker a new ‘compact’ with the industry that would deliver mutually-reinforcing objectives around biodiversity and climate change.

6. Steady and continuing improvements in satellite monitoring means that it is now possible to detect any deforestation going on, on the ground, at an extraordinary resolution. ‘Total transparency’ is the new reality for plantation growers and smallholders alike. This is often seen as a technology that works against the interests of growers, but why shouldn’t governments (at state and federal level) make use of these massively important technological developments to enforce their own policies, rather than seeing this either as a threat or as an unwarranted intrusion into the sovereign rights of governments to determine all land use decisions in their territories?

7. There is now widespread, near-universal acceptance that all future growth in the Malaysian industry needs to come from increasing yields rather than from increasing the land bank available for oil palm. Average estate productivity has improved very little over the last 30 years, and is still stuck at around 20 tonnes of fresh fruit bunches per ha – with smallholder yields significantly lower than that. Increasing average production to 30 or even 35 tonnes per ha is obviously a huge challenge, but all the people I managed to speak to before undertaking this Lecture are very clear that it can – and should – be done as a matter of urgency.

8. Despite the less than impressive performance of members of the Consumer Goods Forum (for the majority of whom a commitment to ensuring ‘deforestation-free supply chains by 2020’ apparently depended on everybody else making it happen on their behalf, even as they did nothing to pay the true cost of making palm oil more sustainable), there are now a number of major companies (including Unilever and Nestlé) which are intent on securing access to sustainable palm oil over the long term, with an emphasis on shared value rather than cut-throat, short-term contracting.

9. The RSPO, despite all the criticism it has to cope with both from Western NGOs and the industry itself (surely some measure of continuing effectiveness for any multi-sector organisation!), has now significantly improved the Principles and Criteria on which any new developments in Malaysia will be approved. Though pretty much unsung on any side of the debate, the RSPO’s continued brokerage role should remind us that progress through negotiated compromise (and I use that word advisedly and not disparagingly) works a lot better than constant confrontation.

So, what are the chances of aggregating all of these different elements into a new initiative here in Malaysia, to get us all out of the embattled positions that people currently feel they have no alternative but to defend? To learn, perhaps, from what’s been happening in Colombia, where sector leaders in the industry joined forces with the Norwegian and UK Governments, as well as a number of prominent NGOs, to sign the first-ever ‘Zero Deforestation Agreement for Palm Oil’ back in 2018? This will require a radical change of heart on the part of all major protagonists to achieve something similar here in Malaysia.

First, Western NGOs such as Greenpeace, Rainforest Action Network, Mighty Earth and so on, will need to recognise that there is a bigger ambition level they should be signing up to rather than sticking with the relatively easy option of endlessly attacking not just ‘the bad actors’ but even those intent on meeting the highest possible standards across their supply chains.

I first felt this kind of frustration during the complex process of reconciling different positions on what is meant by ‘zero deforestation’ during the High Carbon Stock Science Study: any deviation from an impossibly restrictive definition of zero deforestation was characterised as ‘betrayal’ or a sell-out to an industry that is deemed by some to be impossible to trust.

Nearly four years on, I hope those NGOs can now see that this absolutism may not have served them as well as they hoped. Instead of publicly standing up for those companies intent on fulfilling their NDPE commitments, within a reasonable period of time, they’ve become the multipliers of today’s generic demonisation. And the principal consequence of that is that many companies are now re-thinking their market orientation: if every effort they make is met with scepticism, hostility or indifference, leaving the majority of consumers in Western markets persuaded that oil palm is ‘a bad thing’, then why go on bothering?

There is now a widespread belief that more and more companies (particularly in Indonesia) will cast off the constraints of international certification through the RSPO, and focus instead on domestic biofuel markets, as well as exports to China, India, Pakistan and so on – where (for the time being, at least) companies and consumers would appear to have fewer scruples about forests, biodiversity, indigenous people and poor employment practices. From the point of view of accelerating climate change and continued biodiversity loss through deforestation, this is a complete disaster.

By the same token, we would need to see significant shifts in the industry itself, both from producers and consumers. All the ‘good actors’ in the oil palm industry today can no longer stand by as the ‘bad actors’ in their industry continue to put at risk all their ambitions for significant growth in value-adding Western markets. In a world of ‘total transparency’, with satellite technology and the power of big data leaving nobody with any room to hide, this is now the operating reality for the industry as a whole.

Trade bodies need to accept that reality, resisting the temptation to play off MSPO certification against RSPO certification, doubling down in their efforts to support smallholders through improved extension services and new financing mechanisms to enable replanting, and concentrating research budgets on the all-important challenges of improving yields, increased automation, and ensuring resilience in the face of accelerating climate change.

On the consumer side, as I’ve already suggested, both manufacturers and retailers need to deliver on their commitments to ensure deforestation-free supply chains, unequivocally accepting the need to pay a fair premium for traceable, certified sustainable oil, rather than expecting producers in countries much less well-off than themselves to bear that cost on their own.

But the most important player in all of this is, of course, the government, and here I find myself in an ambivalent position: even though part of my mission is to explain to environmentalists in Europe what’s actually going on here in Malaysia (including the commitment to continue to protect the 50% of its territory that is still in natural forest – in comparison, by the way, to the UK’s rather miserable 13%!), I know that the enforcement of that policy is not as rigorous as it should be, and that there is significant encroachment in many of those protected areas. There is no doubt that gazetted forest reserves are being illegally cleared, to within 20 or 30 metres of the boundary of those reserves to conceal the extent of that deforestation.

And despite its best intentions, the Malaysian Government has been slow to move against the bad actors in the Malaysian industry, however problematic it may be to enforce the high standards it seeks uniformly across the entire country. And is there any case at all, given the very welcome emphasis on yield improvement and support for smallholders, to release any more forested land for new oil palm development?

So, no shortage of challenges! But the prize here is enormous: to become the first major producer country in the world able to market every last tonne of oil produced on Malaysian soil as genuinely sustainable, from both an environmental and a social point of view, with traceabilty to the point of origin as a critical element in substantiating that claim, with RSPO certification to back its value-adding export credentials, and MSPO certification for domestic markets (including biofuels) and bulk commodity sales.

After years of confrontation, this may seem unrealistic – and the international community would indeed need to lend its weight to a transformative commitment of this kind. But is there any good reason why the Norwegian Government should not be prepared to back a ‘super-jurisdictional’ approach of this kind, particularly in terms of supporting ‘produce and protect’ measures in both Sabah, and even more importantly, in Sarawak – which has yet to identify itself with a nationwide endeavour of this kind.

And should this not be an absolute priority for the Tropical Forest Alliance, as it seeks to make good on the lofty declarations it made when it was first launched in 2012 – hopefully with the enthusiastic support of my own government’s Department for International Development?

This must surely be a worthy call to action: to bring together all relevant stakeholders to put in place an overarching ‘Sustainable Economic Strategy’ for the industry as a whole by the end of next year? In that regard, I have no doubt that this august body, the Incorporated Society of Planters, will be keen, in its 100th anniversary year, to play its part in bringing together all those parties on whom the industry’s continuing success over the next 100 years so clearly depends.

References

CHAN, H. 2018 ‘Palm Oil Boycotts Not the Answer’, WWF Malaysia, Dec 7, 2018.

http://www.wwf.org.my/?26425/Palm-Oil-Boycotts-Not-The-Answer

GLOBAL FOREST WATCH, 2019 (online only) Country dashboard: Malaysia

https://gfw2-data.s3.amazonaws.com/country-pages/country_stats/download/MYS.xlsx via

https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/global

RAISON, J, ATKINSON, P, BALLHORN, U, CHAVE, J, DeFRIES, R, JOO, G K, JOOSTEN, H, KONECNY, K, NAVRATIL, P, SIEGERT, F, STEWART, C. 2015 ‘HCS+: A New Pathway to Sustainable Oil Palm Development: Independent Report from the Technical Committee’. Kuala Lumpur: The High Carbon Stock Science Study.

http://www.simedarbyplantation.com/sites/default/files/sustainability/high-carbon-stock/hcs-iIndependent-report-technical-committee.pdf

SANCHEZ-BAYO, F, and WYCKHUYS, K A G. 2019, ‘Worldwide Decline of the Entomofauna: A Review of its Drivers’. Biological Conservation, 232 (April 2019): 8-27.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320718313636

WORLD COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT, 1987 ‘Our Common Future’. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019 in Issue 3 -2019, Markets No Comments

Russia’s main consumer of specialty fats is the confectionery industry. The sector ranks fourth in terms of food production domestically after baked goods, dairy products and fish. Since 2000, it has contributed more than 17 billion rubles to the budget annually. It also accounts for 10% of jobs across the food industry and 8% of basic production assets.

The federation ranks fourth in the global production of confectionery, after the US, Germany and the UK. Domestic consumption of confectionery products stands at about 3.5 kg per year per capita. Every year, citizens consume about 770,000 tonnes of flour confectionery products, 500,000 tonnes of caramel and 325,000 tonnes of chocolate.

Currently, about 1,500 specialised and other food enterprises produce confectionery in Russia. More than a third of the total annual capacity of 3 million tonnes is concentrated at the 25 largest enterprises. The largest share of the market is occupied by flour confectionery products (55%), chocolates (32%) and the sugar group (13%).

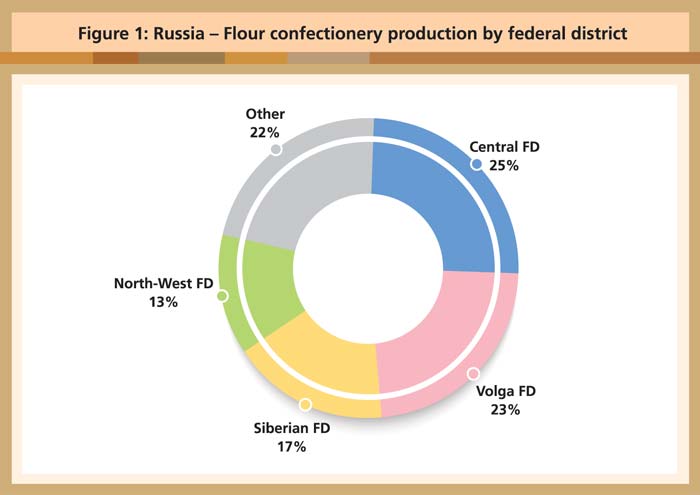

The industry leaders are Concern Babayevsky, OJSC Moscow Confectionery Factory Krasny Octyabr and the Confectionery Factory Rot Front. Foreign manufacturers like Craft Foods, Nestle, Mars and Cadbury contribute slightly more than 12% of the volume produced. The Central Federal District (FD), Volga FD, Siberian FD and North-West FD lead in the output of flour confectionery products (Figure 1).

Source: Federal State Statistic Service

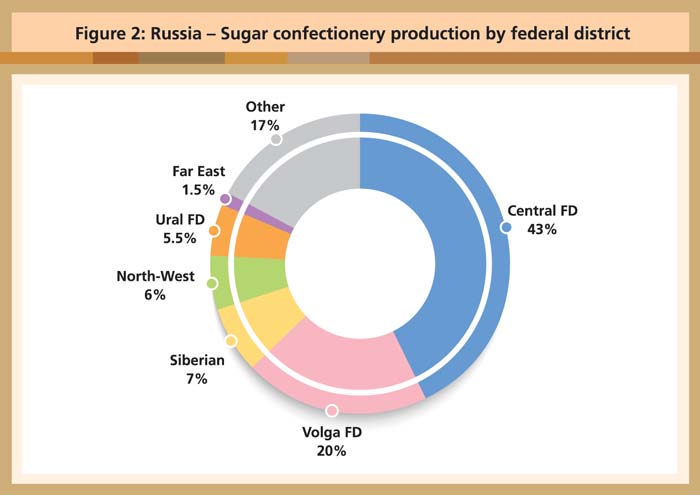

Sugar confectionery products are mainly represented by caramel, lollipops and chocolate. The market is dominated by domestic producers. The share of imports is a little over 20%. The market for domestic chocolate products is saturated and highly competitive, with the average annual growth in production standing at about 5%. The Central FD is the leading producer of sugar confectionery products, accounting for 43% of the domestic volume (Figure 2).

Source: Federal State Statistic Service

Use of specialty fats

Russia is a big producer of specialty fats for the food industry. Although the volume of imports is relatively small, there is potential for higher intake of some specialty fats for the confectionery industry. Two groups of imports – HS 1516 and HS 1517 – are commonly used in this sector.

HS 151620, which represents 99% by value of the HS 1516 group in Russia, comprises vegetable fats and oils and their fractions, partly or wholly hydrogenated, inter-esterified, re-esterified or elaidinised, whether or not refined, but not further prepared.

HS 151790 represents 94% by value of the HS 1517 group in Russia. This comprises margarine, other edible mixtures or preparations of animal or vegetable fats or oils and edible fractions of different fats or oils (excluding fats, oils and their fractions, partly or wholly hydrogenated, inter-esterified, re-esterified or elaidinised, whether or not refined, but not further prepared, and mixtures of olive oils and their fractions).

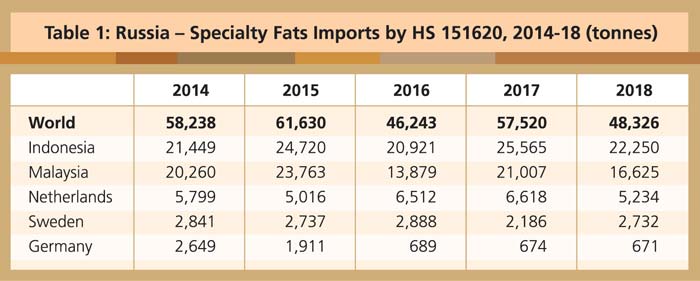

Russian imports by HS 151620 – 48,326 tonnes in 2018 (Table 1) – represent 2.6% of the global trade in these products, with the federation ranked 11th in the world. Its imports by HS 151790 – 49,103 tonnes in 2018 – represent 1.7% of the global trade in these products and it is ranked 13th worldwide. The market value of the two groups was US$171 million in 2018.

Source: Federal Customs Service of Russia

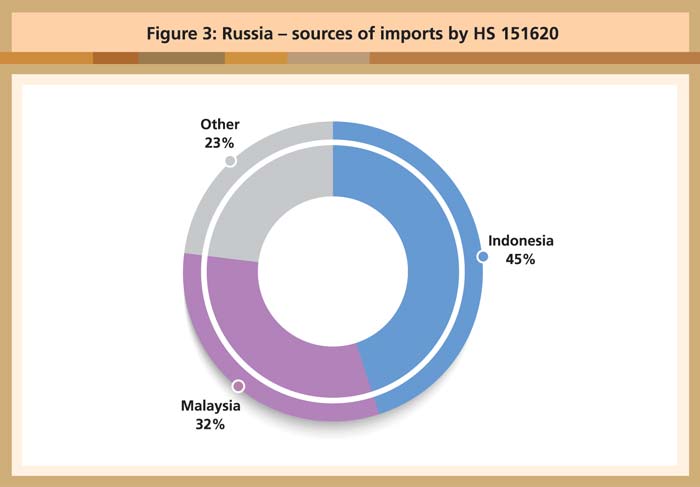

Supplies from Indonesia and Malaysia respectively make up 45% and 32% of the market share for Russian imports by HS 151620 (Figure 3). Other major sources of origin are the Netherlands, Sweden and Germany.

Source: Federal Customs Service of Russia

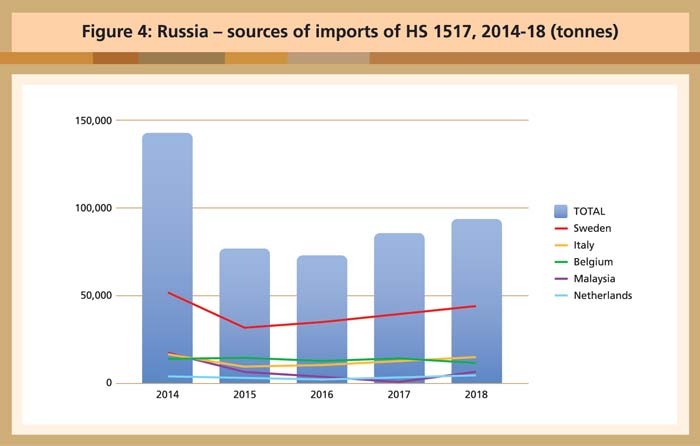

Russia’s imports of specialty fats by HS 1517 are mainly from EU member-states. Sweden is the leading supplier, holding 46.8% the market share (Figure 4), followed by Italy (16%). Malaysia is ranked fourth (7%).

Source: Federal Customs Service of Russia

Malaysia is a leading exporter of affordable specialty fats by both groups. In 2018, it exported over 2.1 million tonnes of specialty fats by HS 151620 worldwide, and was one of the top five suppliers by HS 1517. Given this, there is much scope for Malaysia to compete for a larger share of the Russian confectionery market, recognised as one of the fastest growing in the world.

MPOC Moscow

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019 in Issue 3 -2019, Sustainability No Comments

An ITV documentary film has featured British actress Dame Judi Dench exploring the Danum Valley, the Lower Kinabatangan and Sepilok Orang Utan Rehabilitation Centre in Saba

Read more »By gofb-adm on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019 in Issue 3 -2019, Markets No Comments

Brazil has the largest fleet of cars converted to use the highest blends of ethanol, and the government is reportedly debating whether to remove duties on imports of the US-sourced fuel. As is usual in many countries, the Agriculture Ministry opposes such a move, but others in the government see it as a strategic offering toward a larger bilateral trade agreement.

The US is already the largest supplier of ethanol to Brazil (Figure 1); and when the current 600 million litre import quota expires at the end of August, the 20% duty would still leave American ethanol competitively entering the market. Shipments of biofuel have been a growing market, and the trade war with China has made it more important as an outlet for surplus US agricultural production.

Canada is the second-largest market for US ethanol, but it has been sufficiently saturated. Other large and growing markets include India and Europe, although market access can be an issue. There are also dozens of smaller markets, but the trend in many is to adopt ethanol use. However, a number of them do not have large, inexpensive piles of feedstock like the US.

As corn prices have come down, ethanol is amply competitive with gasoline, while concurrently providing a cleaner burning result when blended. This latter point is particularly a focus for growth in the large cities of Asia.

Some analysts predict an animal protein shock in 2020 that will help consume the current surplus of corn. In the meantime, though, there are both economic and environmental factors driving consumption of the commodity.

Gary Blumenthal

Source: Ag Perspective, Aug 6, 2019

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019 in Issue 3 -2019, Markets No Comments

The Industrial Revolution 4.0 (IR 4.0) trend is transforming the production capabilities of all industries, including the agricultural sector. Connectivity is the cornerstone of this transformation, while the Internet of Things (IoT) facilitates key technologies that enable the development of precision agriculture (PA) and increases the industry’s transparency.

IR 4.0 is seen as a force that will greatly impact agriculture. The trend is built on the use of an array of digital technologies: IoT, big data and Artificial Intelligence (AI). It implies the transformation of production infrastructure toward connected farms, new equipment, and connected tractors and machines.

In essence, this involves digital human-to-machine interaction to raise productivity and quality, as well as to protect the environment. It encourages significant changes to the value chain and business models, with stronger emphasis on knowledge gathering, analysis and exchange.

PA or smart farming requires the optimisation of inputs like water, fertilisers, pesticides and tools to enhance yield, quality and productivity. The farming management concept centres around observing, measuring, and responding to inter- and intra-field variability in crops, using satellite farming or site-specific crop management.

The use of information technology (IT) like satellites, drones, AI and weather forecasting tools ensures that crops and the soil accurately receive what is needed for optimum health and productivity, thus preventing wastage in not only supply, but also time and costs.

Rather than depend solely on human labour to observe the plants and soil to decide what the crops need, satellites and robotic drones can be used to provide a bird’s eye view of the land and give farmers real-time images of individual plants. Information from those images can be processed and integrated with sensors and other data at the whole plantation for immediate and future decisions.

In the past, PA was limited to larger operations which could support the IT infrastructure and other technology resources required to fully implement and benefit from applications. Today, mobile apps, smart sensors, drones and cloud computing make PA possible for farming cooperatives and even smallholders.

In addition, the availability of open-source data from various types of sensors and satellite imagery – such as the USDA’s GADAS, NASA’s Landsat, as well as images from Google Earth – allows smallholders to gain access to state-of-the-art satellite imagery without payment.

When it comes to current farming culture in Malaysia, it must be noted that the average farmer is 50 years old; hence, incorporating or adopting new technology can be a challenge. Embracing change is the only way to attract youth who are tech-savvy into taking up jobs in agriculture. Changing old practices to incorporate the new will also create modern, hi-tech farms.

Analytics, especially for small- and medium-size farms, is emerging as a significant way to improve their gains, especially in developed countries such as the US. Increased access and significantly reduced costs associated with cloud computing have seen a surge in tools and software that allow smallholders to leverage on big data analytics. These technologies utilise smartphone capabilities and low-cost sensors, and make analytics an option for most farmers by increasing cost efficiency.

Analytics have often been seen as an area of expertise of tech-savvy millennials. However, development of mobile apps with a focus on simplicity and user experience can ensure analytics for all. Analytics will be the centre point in driving both improvement in yields and delivery of economic benefits for the modern farm. Productivity will be focused, not on extra human resources, but on data and technology. Technology should not be perceived as a threat to farmers’ incomes, but as a facilitator in growing real incomes over the long term.

PA in oil palm sector

Oil palm plantations can capitalise on PA in three ways: the use of multispectral satellite imagery, drones and remote sensors.

Multispectral satellite imagery

Multispectral satellite imagery encompasses a wide range of graphical vision that conveys information about natural phenomena and human activities on the Earth’s surface. This includes colour and panchromatic (black and white) aerial photographs; multispectral or hyperspectral digital imagery (including portions of the electromagnetic spectrum that lie beyond the range of human vision); and products such as shaded relief maps or three-dimensional images produced from digital elevation models.

The earliest form of geospatial imagery was aerial photography, which consists of photographs taken from an airborne or space-borne camera. Aerial photographs can be taken either obliquely or vertically, which is preferred if the photographs are to be used to prepare maps of an area.

Overlapping vertical aerial photographs can be viewed stereoscopically to obtain a three-dimensional effect that is useful for topographic or geologic analysis, and further used to create topographic maps. Multispectral imagery can be used to assess the condition of a plantation.

Drones/Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)

The ability to collect high spatial resolution aerial data is changing the way oil palm growers are approaching the business. The use of drones allows collection of information to be instantly accessible, and enables planters to make immediate decisions. Precision farming to increase the oil palm yield requires optimisation of returns on inputs, and preservation of resources based on sensing, measuring and health assessment of the plantation.

Professionals have been using satellite and UAV-based remote sensing for plantation monitoring applications such as vegetation cover assessment, vegetation mapping, crop monitoring and forest fire applications. Drone technology focuses on speed and accuracy in delivering that information.

Compared to piloted airplanes and satellite imaging, the ability of UAVs in collecting higher-resolution aerial images at a significantly lower cost can provide oil palm planters with more accurate information on tree height, crown size and the normalised difference vegetation index; this enables data-driven techniques for early and accurate yield estimation and crop-health assessment.

Drones can be integrated with custom instrumentations, controllers, sensors and software to operate as a flexible remote sensing or variable rate technology platform. This can assist in plantation management; growth and soil condition assessment mapping; risk/hazard/safety management; spraying; and research.

Specifically, UAV remote sensing in oil palm PA can contribute to automatic tree detection and counting; automatic measurement of tree height and crown diameter; calculation of planted and unplanted areas for replanting or thinning; analysing the tree status based on Orthomosaics and digital elevation models; inventory management;health assessment based on physical appearances and vegetation indices; model-based yield prediction, yield monitoring and mapping; rapid estimation of nutrient content; and disease detection.

The potential of drones/UAVs in the oil palm industry is immense as it provides a self-operated imaging tool, which is capable of providing regular and timely monitoring of plantations. It is especially useful in tropical countries where clouds are a serious hindrance to satellite image acquisition. The normal sensor camera can capture an image in RGB, while more advanced sensors (multi-spectral) can capture images in extra bandwidths (e.g. red edge, NIR, shortwave Infrared), thereby making classification more effective.

One drawback of UAVs is their lower coverage since they operate at low altitude of several hundred metres above ground level. Nevertheless, this would be sufficient for smallholders, while more could be utilised on bigger plantations.

UAV operations also require knowledge and skills in flying the platform, as well as exploiting the images produced. Critical aspects are the flight planning and geometric processing of the acquired data, including correct positioning of the observations on the Earth’s surface.

Remote sensors

Remote sensing is a tool to provide timely, repetitive and accurate information about the Earth’s surface. It is valuable in monitoring the status and progress of oil palm development. Remote sensing can assist in decision making for efficient plantation management and to investigate the impact of plantations on the environment.

Application-oriented research using remote sensing could generate profits for the industry, while testing the potential of remote sensing in oil palm cultivation. Such research would help resolve or mitigate some of the bigger problems faced by the industry. These include illegal deforestation, spread of disease or pests, nutrient deficiency, yield estimation, tree counting, and monitoring of environmental degradation. Remote sensing would be a useful tool in the early detection and continuous monitoring of these problems.

Application of digital technology

The use of digital technology can facilitate many tasks on oil palm plantations.

Land cover classification

Land cover refers to the composition of biophysical features on the Earth’s surface. As a distinct feature on the Earth’s surface, the oil palm can be detected by remote sensors and imagery. Classifying objects according to land cover helps to differentiate the oil palm from features on adjacent land – for instance, forest, buildings, bare land, water sources and other agricultural plantations. It allows for the demarcation of boundaries and accurate estimation of the area under oil palm.

Tree counting

Tree counting is a necessary practice for yield estimation and monitoring, replanting and layout planning. However, it is costly, labour-intensive and prone to human error when carried out in the field.

Most plantations have resorted to estimating the figures by multiplying the total area with the number of trees per hectare, which obviously is not accurate due to the heterogeneity of the land surface (hilly, undulated or flat) and features (river, land or forest). Remote sensing and imagery is a solution, as it provides a bird’s eye view of the plantation and a way of counting the trees automatically.

Age estimation

Age information is a good indicator of yield prediction, as it influences the quality and quantity of the fresh fruit bunches. Besides, it is an important piece of information to complete the allometric equation for the estimation of biomass. This further indicates the carbon stock of oil palm and its environmental impact.

Age information is important to PA, to detect anomalies among oil palm trees within a common age group. This is required in planning counteractive management practices and optimising resource management. Accurate information on tree age is important for scientific and practical reasons, as it determines the productivity of a tree.

Pest and disease detection

Pests and diseases are of major interest from the management perspective because early detection would help with intervention strategies to prevent outbreaks. Ganoderma boninensis is notorious in the oil palm industry. It is a fungal disease that rots oil palm trees from the inside, causing them to be structurally vulnerable and to topple during strong winds.

The disease is highly contagious. The infected trees rarely show symptoms until the late stage. Such trees have to be quarantined and removed in order to prevent the spread of the disease. Using remote sensing, the health of trees can be assessed based on the symptoms seen at specific spots.

Yield estimation

The oil palm is a commodity with a fluctuating market; as such, its yield has to be estimated through appropriate management strategies in order to maximise profits. Some plantation companies choose to replant the trees when the price is low; or delay replanting when the price is high, disregarding the optimum production age of the oil palm. Yield estimation, as a preliminary step toward yield prediction and forecasting, can aid the decision making process.

The yield is affected by various factors. The internal factors include age and oil palm breeds/variety, while the external factors include rainfall, drought, disease, soil fertility, soil moisture and harvesting efficiency. Thus, to estimate the yield accurately, there is a need to take all factors into consideration.

SWOT analysis

In terms of strengths, digital technologies can reduce manual labour by way of efficient plantation maintenance works. The affordable and long-term use of these technologies would benefit planters in terms of cost reduction, improved productivity and reduced wastage. Application of these technologies will also make the data collection process more efficient.

However, the use of digital technologies in Malaysia is currently limited by the level of expertise among planters, who are more accustomed to traditional ways of plantation maintenance. The potential of the technologies is also limited by 4G network connectivity which, in turn, restricts human-to-machine interaction.

The Ministry of Communications and Multimedia is now testing the first phase of the 5G network, which is expected to be fully launched in 2020. This will reduce the time-lag in human-to-machine communication. Adopting digital technologies will open up plantations to a new generation of employees who are tech-savvy. This will also address concerns about the ageing population of planters, while safeguarding the economic and environmental sustainability of the oil palm industry.

MPOC

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019 in Issue 3 -2019, Markets No Comments

The current global population is estimated to total around 7.5 billion. By most measures, the world creates or produces enough food to feed them all. In theory, the world’s food security has never been higher.

Nevertheless, it is estimated that around 800 million people – more than 10% of the population – are poorly fed or underfed. Their condition ranges from various stages of malnutrition to the verge of starvation. The greatest portion of the malnourished population is in the less developed areas of Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, but a small percentage resides in developed countries around the world, including the US.

The percentage of underfed may well be the lowest in recorded history, and yet it is still a major problem in this time of plentiful and relatively cheap world food supplies. According to the large volume of research on word hunger conducted by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the World Food Programme and a variety of NGOs and academic groups, a number of factors have led to so many being considered malnourished.

Generally, the factors fall into two broad categories: distribution problems, and the affordability of food for the poorest segments of the world’s population.

In fact, there is a long litany of problems standing in the way of food security in Africa and Southeast Asia. One concerns ‘subsistence farmers’ who barely produce enough food on tiny plots to feed themselves, much less market to others. Thanks largely to outside development money provided by charitable groups, this has begun to change in some areas as farmers begin to consolidate their production and marketing. However, the lack of appropriate laws and specific property rights, and a legal system to enforce them, still stand in the way of development of a farm economy in some countries. Poor or non-existent infrastructure is also a major problem.

Also standing in the way are governance problems that include taxing agricultural production to boost government revenues, polices that favour urban populations, blocking technology such as genetically modified (GM) seeds, constant civil strife and corruption (among other issues).

Problems created by government mismanagement and corruption add to food supply and distribution issues in certain developing regions. These problems do not get enough attention in our view. No doubt, the FAO, NGOs and others believe they must take a tiptoe approach to corruption since they must deal with and solicit support from governments and officials involved.

An increasingly popular topic of discussion concerns the ability of the world to feed itself in 2050 when the population is expected to be at least 9 billion. In fact, an Internet search reveals a great deal of interest in the subject. After reaching 30, we stopped counting the discussion papers and articles on the topic. They came from a wide variety of sources, including some with hardly any association with food and agriculture.