The Future of Sustainability Certification

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Sustainability No Comments

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Sustainability No Comments

The release early in March of Greenpeace’s report ‘Certified: Destruction’, which was critical of the certification systems for forest and ecosystem risk commodities, has shifted the focus to the role of certification on the sustainability agenda.

The report had sought to ‘assess the effectiveness of (mainly voluntary) certification for land-based commodities as an instrument to address global deforestation, forest degradation and other ecosystem conversion and associated human rights abuses (including violations of indigenous rights and labour rights)’.

The certification schemes Greenpeace reviewed included the International Sustainability & Carbon Certification; Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance and UTZ; Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO); Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO); Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO); Roundtable for Responsible Soy; ProTerra, Forest Stewardship Council; and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification.

Greenpeace concluded that, while some certification schemes have strong standards, implementation has been weak, having failed to address deforestation and ecosystem destruction, and resulted in the ‘greenwashing’ of products.

‘The weaknesses and flaws identified in the certification schemes assessed in the report make it clear that certification should not be relied on to deliver change in the commodity sector. At best, it has a limited role to play as a supplement to more comprehensive and binding measures,’ it said.

Is Greenpeace throwing the baby out with the bathwater?

“The main conclusion of the Greenpeace report is that commodity-related sustainability certification schemes are not a solution to deforestation and forest degradation. Of course, ‘certification does not equal the definition of deforestation-free’ (to quote the report). It is not meant to be, as the certification schemes are intended to deliver holistically positive outcomes for people, planet and prosperity,” said Teoh Cheng Hai, senior adviser at Solidaridad Network Asia and founding secretary-general of the RSPO.

He added that voluntary sustainability standards such as the RSPO’s Principles & Criteria and national standards can contribute significantly towards the attainment of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, which include the preservation of forests and biodiversity and climate action.

Development of concepts

Global civil society organisation Solidaridad Network subscribes to the view that certification alone is insufficient to achieve sustainability goals. In a 2017 article, Honorary President Nicolaas Roozen had noted that many farmers and companies were already moving beyond certification towards more ambitious post-certification approaches, as the concept had turned out to be an expensive affair with low premiums that often did not reach farmers.

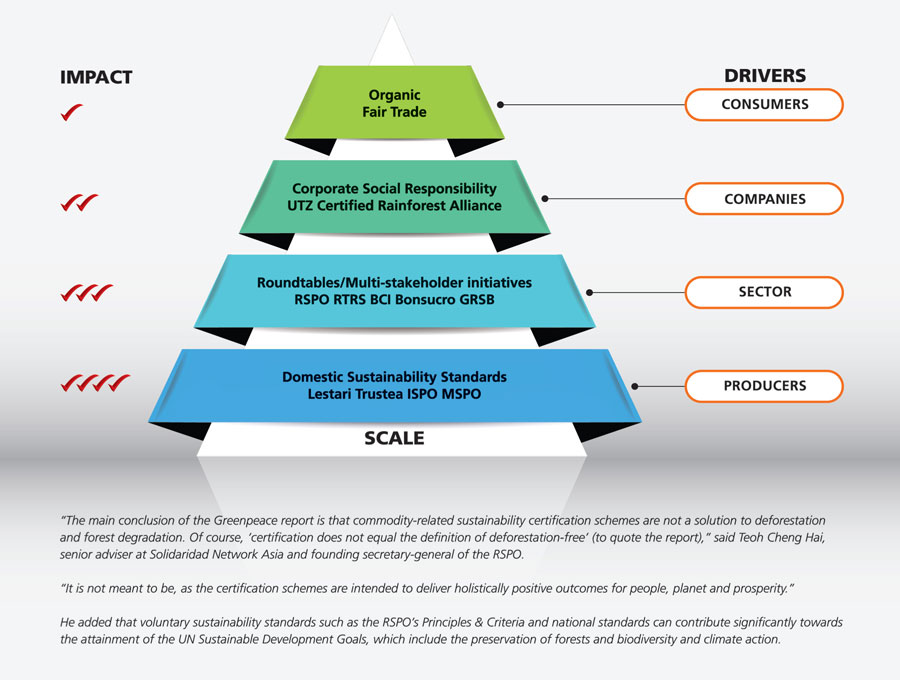

He explained that the sector-wide engagement process of certification – often called roundtables – is but one layer in the “pyramid of change” towards sustainability (see diagram).

The pyramid is a visual representation of the history of the certification process, which had started in the 1980s with consumers driving the demand for certification for organic products, followed by the fair trade system – initiated by Roozen – to improve terms of trade for farmers in developing countries. Both concepts were successful in raising awareness, but the market segments for fair trade and organic were limited at just 3-5%.

“From the perspective of transformative change in the sector, they didn’t make a difference … I think the main obstacle is, of course, the higher price for the consumer,” said Roozen.

Next came the corporate social responsibility (CSR) concept, driven by companies instead of consumers. Companies rebranded their products by adding a sustainable, social and ecological dimension to their marketing and sourcing. Examples include Rainforest Alliance and UTZ, which merged in 2017.

The third layer in the pyramid is the voluntary roundtable process involving sector-wide engagement, which saw the emergence of various roundtables for palm oil, soybean, beef and other commodities.

“The characteristic of a roundtable process is that the sector as a whole is engaged with a sustainability agenda and creates a platform for creating criteria and practices for sustainable sourcing and production. This is an even higher level of commitment and goes deeper into the supply chain [with] a sector commitment expressed by the relevant players of a specific supply chain,” Roozen explained.

“This concept of a roundtable, of stakeholder engagement, offers the opportunity to create scale because the big companies are on the table and are trying to improve and create better practices for the supply chain – not for a specific segment of the product but for the entire sector.”

At the bottom of the pyramid is the development of national standards (such as the MSPO and ISPO), which has made Roozen most excited, as it involves a commitment to sustainability by producer countries and producers.

“What started small scale with consumer preferences could expand its impact through the CSR and roundtable processes. My understanding is that the real change-maker that leads to transformative change is the national standard. Decisive for upscaling sustainability is local ownership and the commitment of local governments to transform the sector to move to more sustainable production, addressing domestic issues and challenges,” he said.

However, national standards are often seen as lower than Western standards.

To this, Roozen put forward Solidaridad’s twofold strategy of “raising the bar, raising the floor”, which is a smart mix of intervention. To illustrate, raising the bar here refers to extending support to smallholders to be included in the RSPO, while raising the floor refers to having the European Commission recognise the importance of national standards such as the ISPO and MSPO.

“One commitment for now is to switch from one-sided focus on the RSPO and give more value and importance to national standards, starting from these keywords. It starts with the recognition that, at the end, national governments have the authority, capacity and responsibility to address issues in their own sector. This is not a foreign agenda but a domestic one. It starts with the acknowledgment of the relevance of the national standards,” he added.

Furthermore, Europe’s imports of palm oil represent only 6% of global production and consumption, making it highly unlikely for this market to effect sector-wide transformation.

“The differentiator for successful transformation will be local ownership and engagement of the main – the most important – consumer countries. In the case of palm oil, they are India and China,” said Roozen, stressing that it is crucial to move from a Western-dominated agenda to local ownership and commitment, supported by demand for sustainable products in the global market.

Common agenda?

India and China are the world’s leading buyers of palm oil.

In 2020, India and China took up 31.4% of Malaysia’s palm oil exports. The EU followed in third place with 11.2%.

“If you don’t get a commitment from India and China to a sustainability agenda for palm oil production, then it’s a lost cause. That’s the way of thinking,” said Roozen.

The good news is, China and India are looking at the sustainability agenda.

India is the first country to recognise the MSPO as equivalent to sustainable, says Shatadru Chattopadhayay, Managing Director of Solidaridad Asia. The country has also set up the Indian Palm Oil Sustainability framework to create social, economic, environmental and agronomic guidelines for palm oil production and trade.

Similarly, interest in and awareness of sustainable palm oil is growing in China, not just because it buys a lot of the commodity but because of its investments in oil palm planting in Africa, said Teoh.

Apart from having national standards, there is also a need to rethink the earnings model of farmers as the way forward in upscaling sustainable agribusiness, said Roozen.

“What changes the world, if you look at the history of addressing social issues, is creating a business case for farmers that enables them to produce in a sustainable way and earn a living,” he said.

For example, the main driver of child and forced labour is the farmer’s inability to afford higher cost of labour.

“If you change the earnings model, he can have better return and income, he can have mechanisation and replace child labour with machinery and technology.”

In changing the perception of palm oil, Roozen said producers and naysayers must define a common agenda, starting with two statements. First, the contribution of the palm oil sector in eliminating poverty. And second, the commodity’s relevance as an affordable cooking oil for the poorest segments of consumers, owing to its high levels of productivity.

“Greenpeace has never made those statements … On those two basic elements, you can define a common agenda. Otherwise, you will always have discussions that are fruitless and will not connect people to address a common agenda,” he added.

Source: The Edge Malaysia Weekly,

March 29 – April 4, 2021

By Editor on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Publication No Comments

For the next few years, the question of pollination was never far from our minds. Our accountants in London were not slow to remind us that we were not making an adequate return on our investment. Pamol Kluang was far more profitable. Apart from the four expatriate-owned pioneering companies, none of the other big Malaysian plantation companies showed any inclination to start operations in East Malaysia.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Markets No Comments

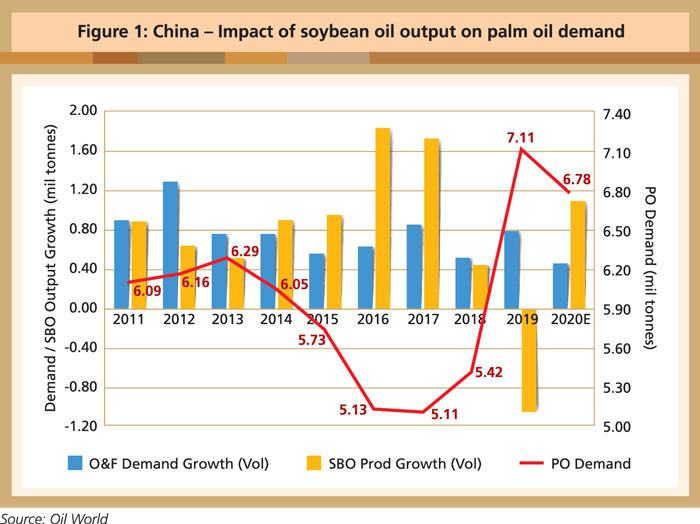

Palm oil is one of the main edible oils and fats consumed in China. In 2020, its market share registered 17% of overall oils and fats consumption, second only to soybean oil at 42%. Two main factors influence the country’s palm oil trade.

Firstly, intake of palm oil is affected by soybean meal demand to feed the growing animal husbandry sector. Higher soybean meal demand encourages local crushing. The resultant increase in soybean oil reduces the spread between soybean oil and palm oil, making palm oil less competitive. When soybean oil output is higher than the demand for oils and fats, palm oil demand will drop (Figure 1).

Secondly, there is a close competition between the two global palm oil suppliers (Figure 2). Indonesia’s lower price strategy and rising palm oil production have affected Malaysia’s palm oil market share in China in recent years. From a high of 41.5% in 2015, the Malaysian Palm Oil (MPO) share fell to 30.2% in 2019.

In 2020, however, the MPO market share in China rebounded to 41.8% because of reduced exports by Indonesia. The volume dropped by 1.5 million tonnes (28.2%) to 3.8 million tonnes, as Indonesia began implementing its B30 biodiesel mandate with effect from Jan 1.

In addition, Indonesia’s palm oil production dipped by 2.1 million tonnes to 42.2 million tonnes due to the lag effect of drought from July to September 2019. The average monthly rainfall then was 57.3mm, or 35.4%, lower than the 88.7mm recorded over the same period in 2018.

Promoting MPO

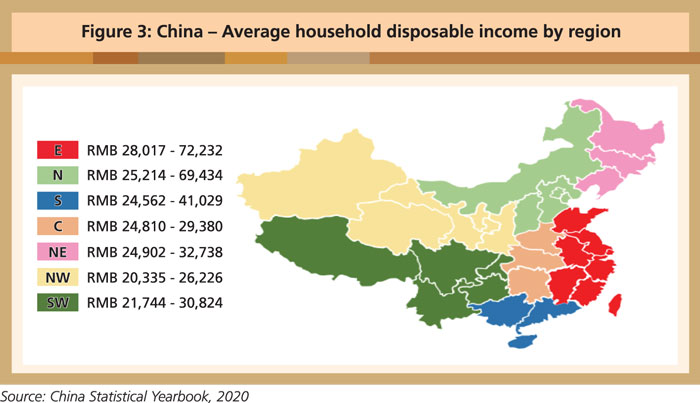

China’s strong economic development remains the key in strengthening the position of MPO. Malaysian exporters should move quickly to take advantage of the resulting changes in consumer demand, higher disposable incomes and impact of urbanisation.

Focusing on product differentiation and strategic partnerships will help Malaysian exporters to ensure long-term demand for MPO products. For instance, the use of palm oil in interior regions such as Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu and Shaanxi is confined to packed fats like shortening for frying. With the expansion of the cattle industry in these regions, there is scope for palm kernel cake to also make an impact.

At the same time, popular tourist destinations like Kunming, Chengdu and Xi’an – which have higher growth in the hotel, restaurant, café and confectionery sectors – offer much potential to improve the sale of palm oil for food.

However, the high cost of transporting palm oil products from coastal ports to inland regions currently impedes sales. Most of China’s interior is served by conventional railway networks. As a result, additional processing and storage facilities would be required to support the expansion of palm oil sales.

Malaysian companies could therefore consider collaborating with Chinese partners to put in place effective logistics, distribution systems and manufacturing facilities. This effort could be strengthened by organising seminars to enhance awareness among small- and medium-scale food processors and distributors on the superior qualities and versatility of MPO applications. End-users also need to be educated on the health and nutrition attributes to motivate their use of MPO products.

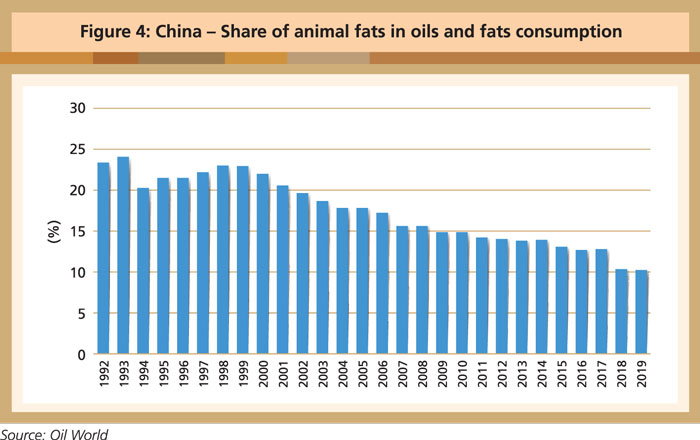

Changes in consumer behaviour in China have paved the way for increased use of palm oil products in recent years. Consumer perceptions about healthy foods have become a major trend in purchase decisions. Individuals are becoming more cautious about the oils and fats they consume, with more people moving away from animal fats due to health concerns.

As a result, the market share of animal fats is being filled by vegetable oils. Based on Oil World figures, animal fats accounted for only 12.7% of oils and fats consumption in 2019, after falling at an average rate of 1.7% per year since 2010. Palm oil players could capitalise on this situation to boost sales in the household sector, via endorsements by respected nutritionists and messages on social media platforms.

One product that could benefit from such focus is Malaysian Red Palm Oil, now that China has allowed the import of up to 20 tonnes of this product per consignment in packed form since mid-2020. Bulk shipments of any volume in flexibags and ISO tanks, for example, have been approved from March 1 this year.

Malaysian Red Palm Oil should be promoted as a healthy cooking oil. Avenues could be explored to blend it with other soft oils, and to encourage its use as an ingredient in bakery product formulations. Malaysian Red Palm Oil is rich in carotenoids (pro-Vitamin A) and Vitamin E. Its vibrant red-orange colour also makes the appearance of margarine, mayonnaise and ice cream more appealing without the use of artificial colorants.

The Covid-10 pandemic has prompted strong demand for hygiene products. Palm-based oleochemical derivatives can be used to make detergents, hand wash and sanitisers. Furthermore, growing demand for green products will compound the demand growth of oleochemicals.

Inner townships have grown rapidly in recent years as a continuing outcome of China’s reform programme. In rural areas, expansion has resulted in the emergence of a new growth market for palm oil products. According to the China National Bureau of Statistics, the rural population in 2019 was 551.6 million. As a result, for every 1kg rise in oil and fat usage per capita, there will be an increase of 551,620 tonnes.

In China, urban dwellers consume more oils and fats than those living in rural areas. Annual per capita intake in urban areas is 23-27kg; in rural areas, it is 15-18kg. Hence, there is a potential for 2.7-6.6 million tonnes of oils and fats to be added to the market, should per capita consumption among rural dwellers reach the level in urban areas. This can be achieved through the development of rural areas. Migration from rural areas is also likely to generate higher consumption of edible oils in urban areas.

Conversely, migration from urban to rural cities will have the effect of improving lifestyle choices and purchasing power per capita among rural Chinese. They will be encouraged to increase the use of refined oils. This will create opportunities to promote palm oil for blending with other soft oils, as it is competitively priced and a good frying medium.

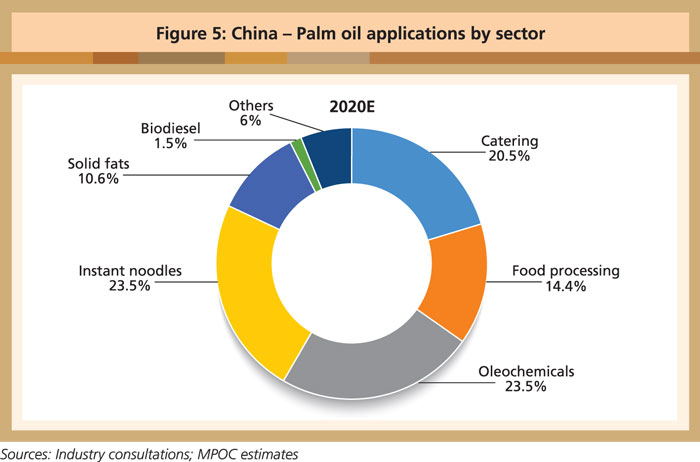

In China, about 75% of the palm oil is used by food-based industries including the catering, food processing, bakery, instant noodles and confectionery sectors (Figure 5).

RBD palm olein is popular in the catering and food processing sectors, although its use in frying instant noodles is dropping off. Most manufacturers are using palm oil instead. Even then, demand for instant noodles is limited in China because consumers prefer heathier food choices and can afford this because of better disposable income.

Oleochemicals command a good share of China’s non-food sectors. As such, Malaysia would benefit from stepping up its exports of oleochemicals and RBD palm stearin.

The bakery and confectionery sectors also hold out promise for enhanced palm oil demand in terms of solid fats. Despite being the second-largest bakery and confectionery market in the world, China’s per capita consumption is only 7.2kg, a far cry from 22.5kg in Japan and 40.2kg in the US. Euromonitor has forecast that the production of baked goods in China will grow by 53% between 2021 and 2025, or at an average of 10% per annum. This shows tremendous potential for higher uptake of palm-based products.

To avoid a price war with other suppliers of solid fats, Malaysian exporters will have to differentiate their products. Where possible, they should work with end-users to formulate bakery products that are unique to customer choices. In other words, Malaysian manufacturers should not merely be suppliers, but strategic partners of China’s bakery sector.

Lim Teck Chaii & Desmond Ng

MPOC China

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Markets No Comments

The world over, 2020 proved to be challenging on all fronts because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Like other countries, India had to find coping mechanisms to keep its economy going. There were several developments in relation to its oilseeds and palm oil trade over the year.

January

Pursuant to the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (FTA), India reduced import duty on CPO from 40% to 37.5% with effect from Jan 2.

On Jan 8, the Directorate General of Foreign Trade issued a notification amending the import policy for refined palm oil and palm olein from ‘free’ to ‘restricted’ status. This was a move to reduce edible oil imports.

As a consequence of strained bilateral diplomatic ties, Indian traders and refiners halted crude palm oil imports from Malaysia from mid-January.

February

Further changes were made to import duties in the national budget on Feb 1. With the ASEAN FTA and Malaysia-India Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (MICECA) in place, the final duty position was:

March

As Covid-19 cases multiplied, an experimental one-day national lockdown was imposed on March 22. From March 25, a longer lockdown took effect – first for three weeks, then for several months.

This had a cascading effect on the economy. The hotel, restaurant and café (HORECA) and food sectors bore the brunt of the slump in business. The HORECA sector, a massive consumer of palm oil, saw its off-take slow down to a trickle. But consumption of soft oils rose, as the preferred cooking medium in households.

May

India resumed its palm oil imports from Malaysian sources, following the resolution of geo-political tensions. By now, India’s stock of edible oils had run down. The price advantage offered by Malaysia was a plus point in increasing imports from this source.

On May 12, India announced its Atma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (Self-reliant India Campaign) to spearhead its economic stimulus package, and to guide strategies during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.

The intention is to promote local agriculture and industries toward self-sufficiency. The government formulated a strong set of forward-looking guidelines – including stepping up oilseeds production – to help India become less dependent on imports of edible oils.

June

Having slowed the march of the Covid-19 virus, the government began phasing out the nationwide lockdown in stages, with Unlock 1.0 taking effect from June 8. This enabled the gradual resumption of economic activities.

The monsoon arrived on time and spread out evenly. It accelerated sowing, and the highest yields in three years are expected for major crops like rice, sugarcane and soybean. Production of groundnuts saw a substantial increase, but it is with mustard that the most significant rise in output is expected.

Production of edible oils is estimated to increase by 1-1.5 million tonnes. This, coupled with subdued demand, should help the country to cut back on imports.

September

On Sept 17, three farm Bills were passed in the Parliament. This was to usher in a new era in agriculture by dismantling archaic rules. The proposals gave farmers the right to sell outside the ambit of their Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee and anywhere in the country. The intention was to empower farmers and afford protection for contract farmers. The Essential Commodities Act was also tweaked. However, the proposals led to protests in some parts of the country.

October

Several important festivals were observed, but in low-key fashion due to Covid-19 safety protocols. The consumption of savouries is a significant highlight of celebrations, usually leading to a spike in the consumption of edible oils. However, inflation in the international market affected the price of edible oils. The prices in October were seen to be 30% higher than in the previous year.

November

The government reduced the import duty on CPO from 37.5% to 27.5% with effect from this month. Duty was retained at 45% on RBD palm olein and at 54% on RBD palm oil.

December

Unlock 7.0 was the last of the lockdown phase-outs for the year. Among other provisions, restrictions on the movement of goods and people within and between states were lifted. Anticipating the rollout of locally produced vaccines, India looked forward to better protection of its population from the Covid-19 virus.

Although the situation seemed to be on track, the second wave has since struck with a vengeance and India has been pushed back by many steps. It is hoped that India will overcome the crisis, and that the march forward of the economy and the people will resume in earnest.

Bhavna Shah

MPOC India

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Markets No Comments

India is one of the world’s largest producers and consumers of edible oils and fats. It has the largest harvested area for oilseeds, accounting for 21% of the global acreage, and contributes 5% of production worldwide. The anomaly in harvested area and production level is rooted in the abysmally low yields.

At the same time, India is one of the biggest buyers of edible oils. It imports about 15 million tonnes of edible oils every year, as domestic production meets only 7-8 million tonnes of needs. Palm oil holds the largest share, at about 65% of imported oils (Figure 1).

Over the next five years, India’s edible oils consumption is expected to rise by 2-3% per annum, depending on economic and population growth. In such a situation, bridging the huge gap between imports and domestic output will be a major goal under the government’s Atma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (Self-reliant India Campaign).

If India wants to produce as much edible oils as it is consuming through traditionally- grown oilseeds (Table 1), it would need at least 30 million ha for cultivation – which would be next to impossible.

The Department of Agriculture has therefore set a target of first increasing oilseeds production from primary sources from the current 31 million tonnes to 45 million tonnes by 2022-23. This is expected to help increase production from 7-8 million tonnes now, to a range of 10-11 million tonnes and then gradually up to 14 million tonnes. Contributions from secondary sources and tree-borne oilseeds are likely to add another 3 million tonnes by 2022-23.

Only oil palm cultivation can produce 4 tonnes of oil per hectare, where other oil crops don’t even yield 0.4 tonnes. Thus, the emphasis is on increasing oil palm cultivation. The objective is not only to bring about self-reliance in edible oils output, but also to transfer money to farmers from the amounts currently spent on imports.

To stimulate oil palm cultivation, a price incentive mechanism has been suggested for farmers, through the creation of an Edible Oils Development Fund. The contributions would come from levying a cess of 0.5% on the import of palm oil products.

On July 23 last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had appealed to farmers in the North-East States to take up oil palm cultivation. In 2019-20, the government had extended the area under oil palm by 17,000 ha, mainly in Mizoram, Assam, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh. It plans a further expansion in 2020-21 as part of the National Food Security Mission.

Last December, the government had allotted 0.3 million ha to various companies and organisations for the cultivation of oil palm in Telangana state in the south (Table 2). The anticipated rise in production will make Telangana the first state to become self-reliant. It will also be able to sell its surplus to other states.

National mission

There is a dichotomy between farm prices and consumer prices. When farm prices are buoyant, farmers get reasonable returns while consumers bear the burden of paying more for products. When there is a glut, products do not command a fair price – this dampens the farmers’ mood but provides for a lower price to consumers. Also, with 65% of India’s population being farm-dependent, the differentiation between farmers and consumers is often glossed over, as farmers are also consumers.

The government has to balance the interests of various stakeholders, as farmers, industry, the exchequer, consumers and others push for policies that best meet their needs. The national interest must also be kept in mind.

The government is planning to work in ‘mission mode’ to reduce dependency on imports of edible oils by raising local production, and spreading public awareness of the need for rational consumption. Under the National Mission on Oilseeds, there is a plan to spend nearly US$2.6 billion over the next five years, as reported in Times of India on Feb 21. The preparations for the mission are said to be foolproof and the plan will be implemented from April 1 in the upcoming financial year.

Earlier, a fund of about US$1.4 billion had been mooted to support the National Mission on Oilseeds and Oil Palm for five years. However, the Group of Secretaries is now looking at raising the money by levying a cess on the industry instead. The industry, though, wants the government to set aside a corpus – the principal sum – from the revenue earned from import duty on crude and refined edible oils.

To increase the production of oilseeds alongside acreage, more emphasis will be given to improving productivity. For example, in the eastern region, nearly 11 million ha are not utilised after the paddy crop is harvested. This can be used for growing various oilseeds or oil crops.

In addition, farmers will be encouraged to cultivate pulses and oilseeds instead of crops like paddy, wheat and sugarcane in Punjab, Haryana and other areas in northern India, where water is scarce. These crops are in abundance anyway, with annual surpluses. The transition away from growing grains is a key step in the government’s mission to boost oilseeds production.

Mustard cultivation in ‘mission mode’ has already increased in acreage this year, with output anticipated at between 11 and 12 million tonnes. Similarly, the production of other oilseeds could double over the next 5-8 years. With capital, government support, the right technology and execution, it will be possible to gradually grow oilseeds on various types of available soil.

Apart from seasonal crops, oil is obtained from the seeds of some evergreen trees in the country. There are also secondary sources of oil. The goal of development has been set at every level. Four ‘Sub-Missions’ have been created under the National Mission on Oilseeds (Figure 2).

Increasing investment in edible oils is among the government’s top priorities. To transform agriculture into sustainable enterprises, the central government has proposed the formation of 10,000 Farmer Producer Organisations. Of these, 100 are registered only for oilseeds and are allocated to four organisations – National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development; National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India Ltd; Small Farmers Agribusiness Consortium; and National Cooperative Development Corporation.

The attempt to make farmers self-reliant though free market mechanisms at this time of an economic slowdown is aimed at increasing their income. It will also allow farmers to engage directly with agri- business companies, exporters and retailers for services and sale of produce.

Self-reliance in edible oils can provide much needed food security to the nation in an uncertain world order. But it will bear fruit only if the central and state governments work together, and if short-term concerns about food inflation are not allowed to hinder progress and determine trade policies and import tariffs.

Bhavna Shah

MPOC India

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Markets No Comments

Within a gloomy global scenario marked by extensive lockdowns, movement restrictions and social distancing to curb the Covid-19 pandemic, economic growth and routine business dynamics have been severely constrained since January 2020. Every industry has struggled to find new ways to cope with sudden demands thrown up by a much-changed market place and consumer preferences.

It was no different for the Malaysian Palm Oil industry, although it eventually posted a creditable performance in 2020. This was partly due to a recovery of prices, as the global economy adapted to challenges posed by the pandemic. Demand for palm oil picked up, and the price rose to close at RM3,600/tonne at the end of the year.

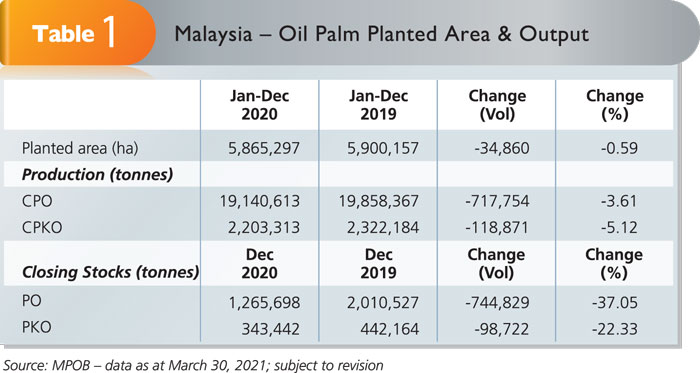

It was not all plain sailing, though. Malaysian CPO production dropped by 717,754 tonnes (3.6%) to 19.1 million tonnes (Table 1). A shortage of workers affected harvesting of fresh fruit bunches, leading to lower processing. Another factor was that the oil extraction rate fell to 19.9% (by 1.4%) from 20.2% in 2019.

The oil palm planted area fell by 34,860 ha (0.6%). Replanting in some areas was delayed because of the low palm oil price, especially at the beginning of the year. The year-end palm oil stock level dropped by 744,829 tonnes (37.1%) to stand at 1.3 million tonnes. PKO year-end stocks declined by 98,722 tonnes (22.3%) to 343,442 tonnes due to lower production and higher domestic consumption.

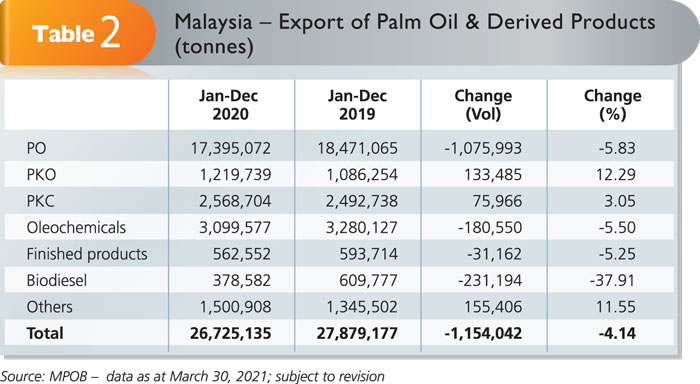

Overall exports of palm oil products fell by 1.2 million tonnes (4.1%) to 26.7 million tonnes (Table 2). However, PKO sales improved by 133,485 tonnes (12.3%) year- on-year.

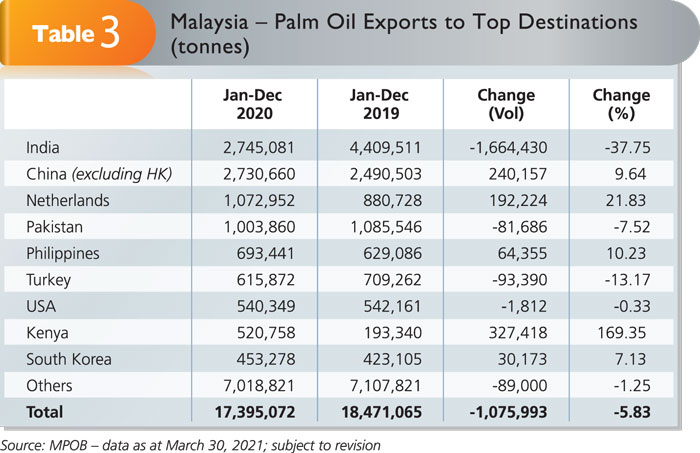

India remained the leading importer of Malaysian Palm Oil for the seventh year in a row, with 2.7 million tonnes (Table 3). However, its volume was lower by 1.7 million tonnes (37.8%) due to competition, as well as the narrowing spread between the price of soybean oil and palm oil domestically.

India’s imports from Malaysia slowed from January to April 2020 because of geo-political tensions. In addition, domestic business operations were shut down by a national lockdown and movement restrictions linked to the control of Covid-19. Demand for palm oil fell in the hotel, restaurant and café (HORECA) sectors, which are typically substantial users.

China’s imports of Malaysian Palm Oil rose by 240,157 tonnes (9.6%) to satisfy the demand for vegetable oils. There was a shortfall because domestic soybean crushing activities were reduced. In addition, palm oil stocks were depleted early in the year, necessitating an increase in imports.

The Netherlands, Pakistan and the Philippines were the other significant importers of Malaysian Palm Oil for the year.

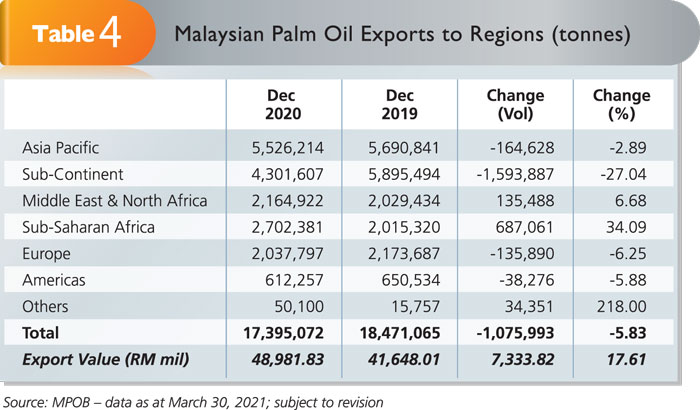

Crude and processed Malaysian Palm Oil exports made up 17.4 million tonnes and were valued at close to RM49 billion (Table 4). Although the export volume fell by about 1.1 million tonnes (5.8%), the value increased by RM7.3 billion (17.6%) due to price recovery in the second- and third-quarter of the year.

Price movements

The trend of lower palm oil prices from June 2019 carried through into 2020, but staged a mini-recovery in February. However, the pandemic and collapse of crude oil prices pulled down the palm oil price from RM2,986/tonne in January to RM2,050/tonne in May. It then strengthened to between RM2,400 and RM3,600 per tonne from June through December

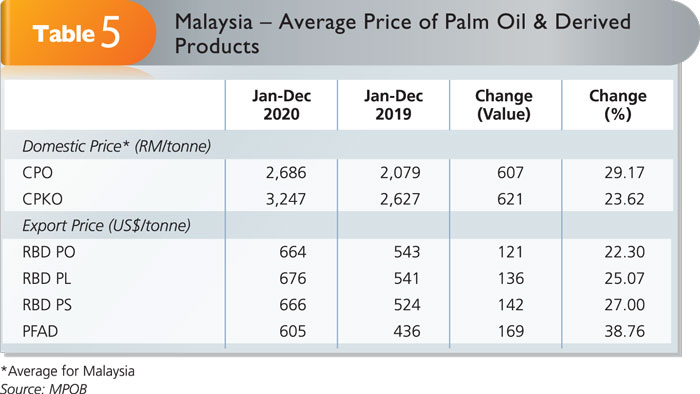

The annual average local delivered CPO price increased by RM607 (29.2%) to RM2,686/tonne (Table 5), because of a production shortfall and low monthly domestic stocks. Prices of competing vegetable oils also rose over this period due to concerns over supply shortages. For example, the soybean oil price rose by about 34%.

As demand switched to palm oil, its price was pushed up as well. The highest average monthly traded Malaysian CPO price was seen in December at RM3,620.50/tonne, while the lowest was in May at RM2,050/tonne.

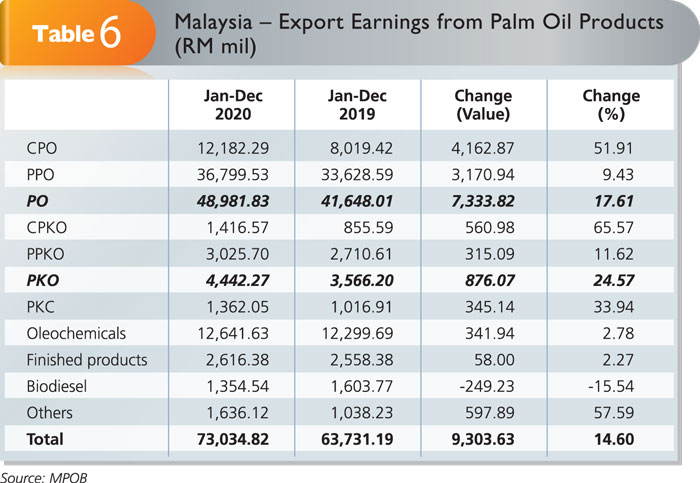

Earnings from exports of Malaysian Palm Oil products went up by RM9.3 billion (14.6%) to exceed RM73 billion in 2020, even though the volume was smaller (Table 6). This was attributed to a steady rise in the palm oil price, in particular during the second half of the year.

Crude and processed palm oil exports alone brought in close to RM49 billion (up by 17.6%), compared to RM41.6 billion in 2019. Revenue from CPKO and PPKO exports was higher by RM876 million (24.6%). An increase of RM341.9 million (2.8%) was recorded from exports of oleochemicals, while sales of other palm oil products saw earnings rise by RM597.9 million (57.6%). Only biodiesel exports returned a lower revenue of RM249.2 million – a drop of 15.5% due to a 231,195-tonne reduction (by 37.1%) in volume.

Global oils and fats trade

The difficulties posed by Covid-19, as well as demand disruptions, did not greatly affect the need for edible oils during the year. Soft oils assumed greater importance in households, because the HORECA sectors were closed under Covid-19 restrictions. Economic recovery in the second half of the year, coupled with increased global consumption of processed food, helped sustain the demand for edible oils.

Global production of oils and fats stood at just over 235.7 million tonnes, a marginal decrease of 0.8 million tonnes (0.01%) compared to 2019. Oils and fats consumption registered 236.7 million tonnes against 238.2 million tonnes previously, or 1.5 million tonnes (0.01%) lower year-on-year.

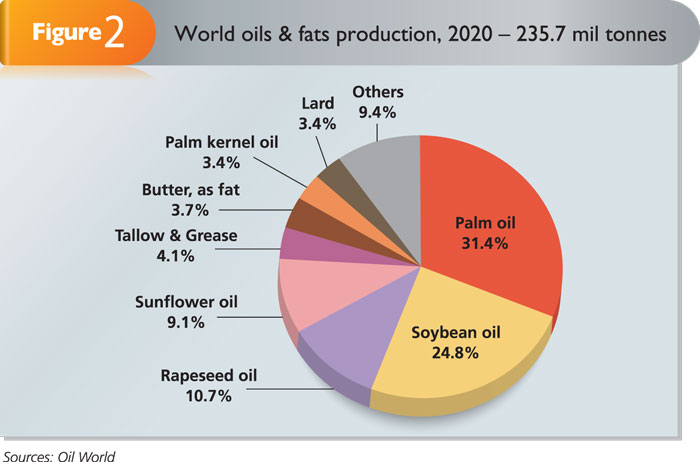

Palm oil and palm kernel oil jointly accounted for 81.9 million tonnes or 34.8% of the world’s oils and fats output (Figure 2). Soybean oil registered 58.4 million tonnes (24.8%), while rapeseed oil recorded 25.3 million tonnes (10.7%).

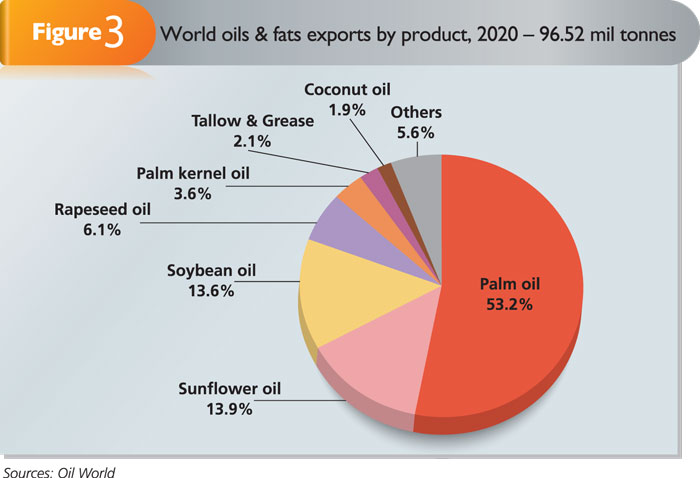

Of the 96.5 million tonnes of oils and fats traded globally, palm oil and palm kernel oil together made up 54.2 million tonnes or 56.8% (Figure 3).

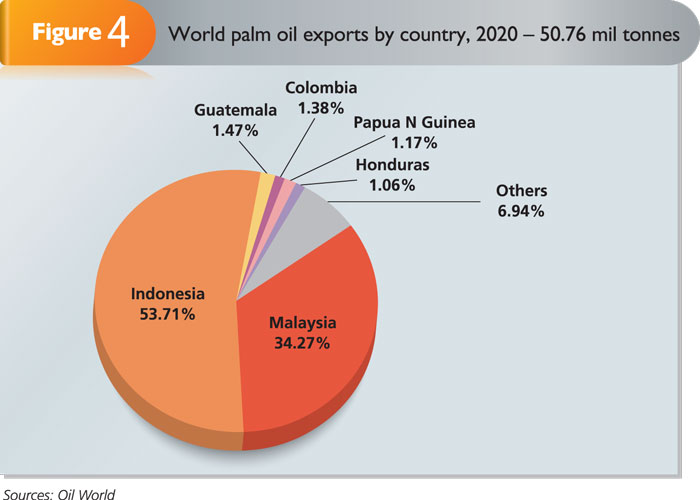

Malaysia’s exports of 17.4 million tonnes of palm oil represented 34.3% of the 50.8 million tonnes supplied by all producers (Figure 4).

MPOC

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Markets No Comments

Issues involving Covid-19 and Brexit have dominated attention in the UK over the past year. The country has been one of the worst affected in Europe by the pandemic, even as it grappled with the legal complexities of leaving the European Union (EU). But what are the implications of both issues for the UK’s palm oil trade?

Take Covid-19. The initial wave ran roughly from January to June 2020, and was more severe than on much of the European continent. In December 2020, a mutation of the coronavirus named B.1.1.7 was discovered in the UK. It proved to be much more contagious than the original virus. Consequently, the government had to announce a third lockdown on Jan 4 this year.

And Brexit? For years, this debate was at the heart of the daily news in the UK. Now the separation is complete. The UK officially left on Jan 31 last year, but the transition period only expired at the end of 2020.

Politicians, businesses and the population were supposed to prepare for the exit. This went down to the wire. Shortly before the deadline and with a no-deal scenario looming, EU representatives and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson finally agreed on rules to organise future relations.

After 4½ years of uncertainty and speculation, a Trade and Cooperation Agreement negotiated between the EU and the UK entered into force provisionally on Jan 1 this year. It puts their economic relationship on a new footing.

The deal establishes, among other things, a comprehensive trade partnership. At its core is an agreement providing for neither tariffs nor quotas for virtually all products exchanged between the UK and the EU.

However, there is a caveat: A prerequisite for duty-free treatment is compliance with the rules of origin. Duty-free treatment applies only to products originating from the contracting parties. In other words, it is only granted if goods originate in the EU or the UK.

There are several qualifications as to what ‘originating in the EU’ means. Among them is a stipulation that considers goods originating outside the UK as eligible for free trade treatment if they have been sufficiently worked or processed. Only a certain proportion of input materials from third countries may be used. Product-specific rules of origin are to be observed.

UK palm oil trade

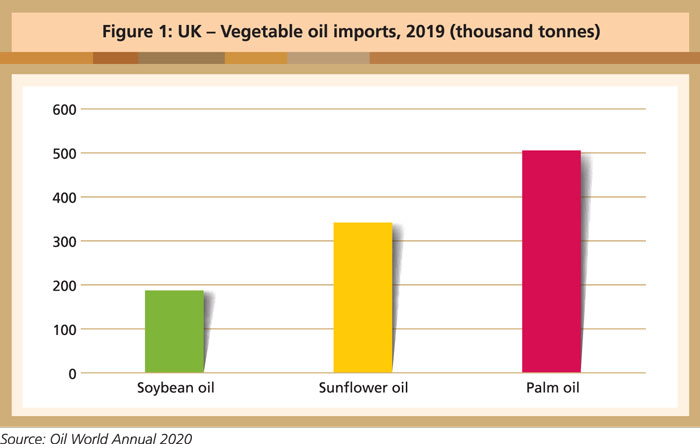

Based on the latest available Oil World figures, the UK in 2019 imported 505,900 tonnes of palm oil, making it by far the leading vegetable oil import (Figure 1).

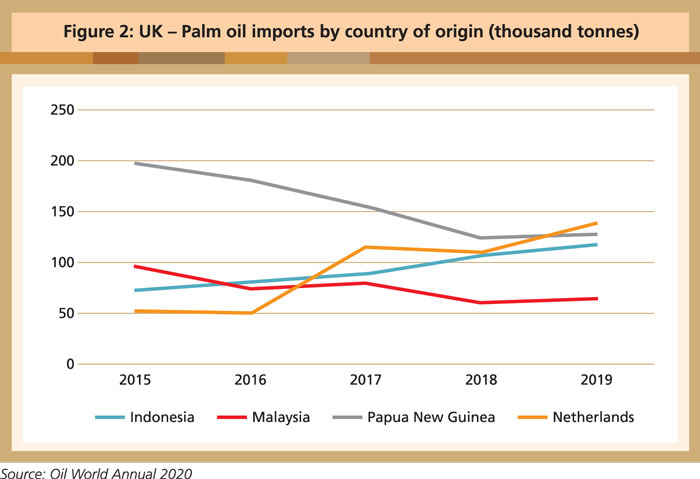

The import volume includes shipments via intra-EU trade. The leading country of origin for palm oil imports in 2019 was the Netherlands, followed by Papua New Guinea (Figure 2). The volume that the UK sourced directly from producing countries stood at 320,000 tonnes.

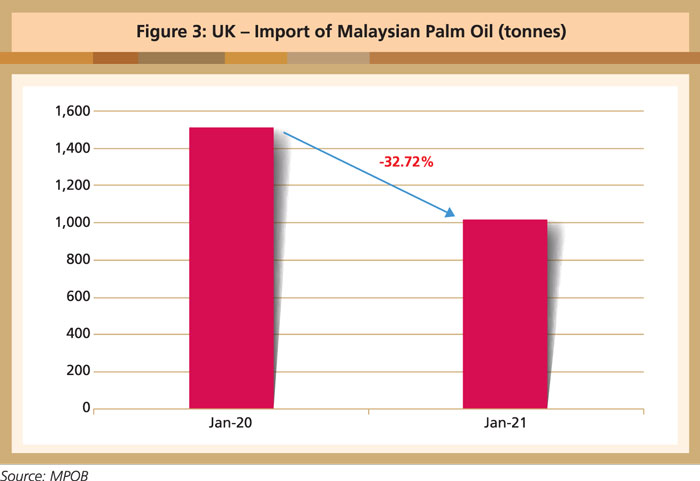

The Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) recorded an export volume of 15,505 tonnes of palm oil to the UK from January to December last year. There was a decrease of more than 32% in the comparative volume for January 2020 and January 2021 (Figure 3).

One reasonable interpretation of the MPOB data is that they show the double effect of Brexit and Covid-19 on the UK’s economy. Its GDP last year had shrunk by a full 9.9%, which was worse than in most European countries. Many observers point out that this was the poorest economic performance since 1709 when the ‘great frost’ led to a failed harvest.

Variable prospects

The UK economy will remain in dire straits this year for the same reasons – Covid-19 and Brexit. An overall slump in demand for palm oil in projected, as the Covid-19 lockdown takes its toll on the hotel, restaurant, tourism and transport sectors in particular. Brexit issues have also severely hampered trade with the EU, which has been the UK’s most important partner.

The British Road Haulage Association sounded the alarm in a letter dated Feb 1, 2021, to Michael Grove, the Minister for the Cabinet Office. It reported a 68% drop in UK exports to the EU, compared to the previous period. At the same time, many EU goods cannot find their way across the Channel, leading to an increase in consumer prices, as well as further lowering demand.

Amidst this, however, there is a possible upbeat scenario for palm oil. First, the post-Brexit trade agreement contains provisions on rules of origin that conceivably might work in favour of palm oil. They aim at zero tariffs or quotas on goods traded between the UK and the EU – provided the rules of origin are satisfied.

The rules entered the agreement because the EU obviously wants to avoid circumvention should the UK import duty-free items from third countries, and then re-export – also duty-free – to the EU.

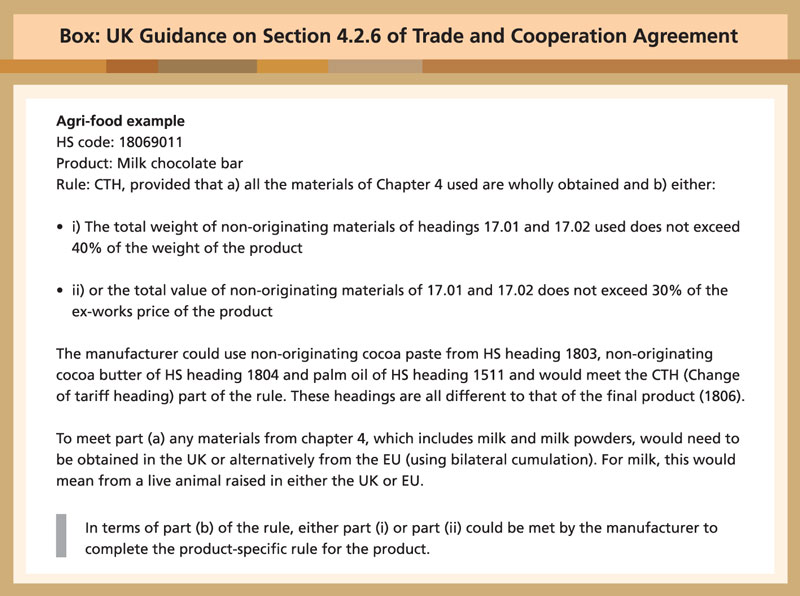

However, there may be certain exemptions for palm oil, based on guidance published by the UK government in relation to Section 4.2.6 (see Box). It appears to imply that products like chocolate bars containing palm oil can continue to be exported duty-free to the EU.

A second segment that might be favourable for palm oil concerns biofuels. Now that the UK is no longer in the EU, the rules of the RED II on phasing out palm oil in biofuels by 2030 no longer apply. The emerging scenario is still foggy, and issues of how the UK and the EU will design that part of its relationship have been delegated to expert groups.

Still, the chances are that the UK is keen on getting on the right side of palm oil-producing nations in Asia, as it wants to strike trade deals in line with its ‘Global Britain’ initiative. As Bloomberg had opined in 2019: ‘Post-Brexit, the UK will have a historic opportunity to strike a trade deal with one of the world’s fastest-growing regions and prove that it can shed European red tape and protectionism. The key is to rethink the European Union’s policy on palm oil.’

This assessment points to a trend that could work in favour of palm oil in the long term. ‘Global Britain’ is the UK government’s mantra for redefining the country’s role in a post-Brexit world. Large portions of the concept still have to be filled with substance, but a charm offensive regarding Asia is already underway – and palm oil is a central issue there.

On Feb 1, 2021, Great Britain formally applied to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, of which Malaysia is a founding member. The UK is the first non-founding country to apply for membership. And its government is wary of the fact that palm oil could become a sticking point in the negotiations.

Jon Lambe, UK ambassador to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, has been quoted as saying: “From my perspective, this is an area where it is important we work together. There is a strong consumer demand in the UK for palm oil and palm oil products. There is a strong industry in Malaysia and Indonesia and it is vital that we work together to ensure that both ends of that supply chain are content.”

It is therefore possible that Brexit will usher in a new dawn for palm oil in the UK – and for Europe, through the British back door. Due to Covid-19, though, this could take time.

Uthaya Kumar

MPOC Brussels

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Comment No Comments

Malaysia will review the European Union’s (EU’s) reasoning in phasing out palm-based biofuels under the Delegated Act of the revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED II).

Plantation Industries and Commodities Minister, the Hon. Dato’ Dr Mohd Khairuddin Aman Razali, said a Malaysian government delegation had held consultations with EU representatives on March 17, via the Dispute Settlement Mechanism of the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Malaysia had filed a complaint before the WTO, according to a Ministry statement issued on Jan 15.

The country is seeking a fair judgment over the EU’s action, which will exclude palm oil as part of the EU’s biofuels mix by the end of 2030. Malaysia also wants the EU to redefine its interpretation of oil palm cultivation, which the latter has classified as ‘high-risk’.

The consultation process is among efforts to arrive at a solution over the EU’s action, which Malaysia deems to be discriminatory, the Minister said in a statement.

“Malaysia will review the feedback and clarification provided by the EU throughout the consultations. Further action will be taken accordingly, guided by the rules and procedures that have been outlined by the WTO.”

Malaysia’s representatives at the consultations comprised officials of the Attorney-General’s Chambers, International Trade and Industry Ministry, Foreign Affairs Ministry, and Water, Land and Natural Resources Ministry.

Indonesia and Colombia acted as observing countries, with both being members of the Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries.

Under RED II, the EU is moving to raise the share of renewable sources in the energy consumption mix to 32% of the total energy consumption, while phasing out the inclusion of palm-based biofuels by 2030.

The EU has claimed that oil palm cultivation contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation and indirect land-use change, and is therefore a ‘high-risk’ activity.

Indonesia’s complaint

Indonesia, the world’s biggest producer of palm oil, had filed a complaint before the WTO in December 2019, on the basis that the EU’s restrictions on palm-based biofuels are unfair.

Malaysia is a third-party observer in the case, along with countries such as Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Thailand, Australia, Brazil, the US, Costa Rica and India.

China, Canada, Singapore, Turkey, Norway, Russia, Argentina and Japan are also taking an interest in the matter.

The consultations held on Feb 19 last year had failed to settle the dispute, leading to the establishment of a panel to adjudicate the issues.

Indonesia and Malaysia are the world’s top producers of palm oil, supplying about 85% of the output.

Source: The Malaysian Reserve.com

March 19. 2021

This is an edited version of the report.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Comment No Comments

As countries roll out Covid-19 vaccines and economic reopening strategies, another crisis lurks: climate change. How governments approach economic recovery will determine how fast they bounce back from the pitfalls of 2020. Yet, it will also be a crucial indicator of how they will fare in the face of future crises. While some countries are using this as an opportunity to ‘build back better’, developing nations are struggling to keep up – a situation which will leave the world vulnerable to disaster.

Covid-19 has severely impacted our economies. Industrial nations of the North are encountering recessions greater than the 2009 financial crisis – for instance, the UK’s economy fell 9.9%, double what occurred in 2009 – and poorer countries of the South are predicted to lose a decade of development. But scientists are already looking beyond the impending recession to calculate the next calamity. If the world does not address climate change and rising carbon emissions by developing a new ecological approach, rebuilding successful economies in a post-Covid world will be fruitless.

For the foreseeable future we need to stimulate the receding economy while prioritising the environment. A new paper published in the peer-reviewed Global Policy Journal (GPJ) believes this can be accomplished through new trade deals and ecological pacts – crucially, a North-South ‘Green Deal’, a global environmental coalition led by the EU, which would encourage sustainable production and boost economic trade.

The UN has already encouraged all governments to view post-Covid recovery as a chance to integrate sustainability practices into economic models, overturning pre-Covid systems and building post-Covid solutions which support net-zero pledges and the Paris Agreement.

Disappointingly, the latest UN report revealed that only 18% of the US$1.9 trillion allocated for recovery from Covid-19 can be considered ‘green’. While disappointing, it is not unsurprising, given that the enduring economic model does not reward environmental collaboration or accountability. Indeed, it leaves too much room for narrow-minded solutions and paves the way for deadly mistakes.

Global coalition

Even with the lessons of Covid-19, the world keeps forgetting we are intrinsically connected. If the North succeeds in implementing its versions of the Green Deal – switching to clean industrial innovation while curbing carbon emissions – the planet will still be vulnerable as the South is forced to rely on fossil fuels and deforestation to attain economic stability. If Northern trade blocs, like the EU, truly hope to transition to a post-carbon future and meet Green Deal promises, they must realise this cannot be achieved in isolation.

This would mean reimagining the current approach. The EU has notoriously overlooked partnership opportunities with producer nations. For example, in an attempt to combat imported deforestation, the EU has banned the import of palm oil as a biofuel from 2030. However, this de facto ban has unintended consequences and, as stated in the GPJ, created a trust deficit between the EU and Asia – which believes the EU is ignoring science in lieu of its protectionist tendencies.

The oil palm, which is an incredibly efficient crop, is able to produce more oil per hectare of land than the EU’s replacements of soybean, rapeseed, coconut and sunflower. Importantly, Europe’s ban does not stop producer nations from cultivating oil palm. It is believed this ban will only force these nations to sell palm oil to China and India – meaning there will be less pressure for palm oil to meet sustainable standards. Ultimately, the EU’s boycott will cause displaced deforestation and diminish efforts in producer nations to meet sustainable goals.

What the EU seems to be overlooking is that trade is an important tool in achieving environmental protection and economic growth. Trade can be a catalyst; a prime example is a recent UK Environment Bill which reveals supply chains and curbs deforestation by forcing UK businesses to import commodities which abide by the environmental laws of producer nations. This obliges UK businesses to collaborate with manufacturers, and incentivises policies which encourage sustainable production.

If the EU can do something comparable, then they can enter a coordinated, global Green Deal which prioritises sustainable economies and guarantees prosperity for humanity and the planet. If the EU adopts this mindset, it could partner with existing mandatory regulations, like the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil certification scheme, which if guided by the EU could be better enforced and implemented.

We need a new economic approach which emphasises the environment – a global pact which values mutually beneficial relationships, and encourages the world’s finest sustainability practices across energy, agriculture, transport and health. Importantly, we must address the root causes of pandemics and economic inequality.

Global coalitions can transform national, narrow Green Deal promises into global systems of sustainable advancement and prosperity; new models which offer protection from novel diseases, impending recessions and destructive climate change – the emergencies of tomorrow.

Professor Ibrahim Ozdemir

Ecologist

Source: The CSPO.org, March 23, 2021

This is a slightly edited version of the article, which is available at:

https://commentcentral.co.uk/north-south-green-deal-best-antidote-to-looming-recession/

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Sustainability No Comments

A new United Nations report warns that 12.5% of all plant and animal species face extinction because of a systemic failure to address climate change. A separate report from the UN flatly states that nations are ‘nowhere close’ to the level of action needed to fight global warming.

Scientists have weighed in on the issues and warned of a ghastly future and identified the problems as being ‘compounded by ignorance and short-term self-interest, with the pursuit of wealth and political interests stymying the action that is crucial for survival’.

These reports are hardly surprising. Over the past 40 years, wildlife populations have declined by an astonishing 60% as the world’s richest countries continue to fail the fight against climate change.

A historic ruling by a Paris court could, however, set a precedent for climate action. The court convicted the French state of failing to address the climate crisis and not keeping its promises to tackle greenhouse gas emissions.

France is the perfect example of a country’s failure to address climate change and biodiversity despite big pledges and commitments on paper. No other country exemplifies this ‘ghastly future’ where short-term self-interest is placed before the good of the common.

As a political and economic powerhouse within the European Union (EU), its failure to meet previous commitments presents a challenge to the EU, as the union makes new commitments towards fighting climate change and protecting biodiversity.

In a nutshell, France capitulated to the demands of its rapeseed farmers and decided to ban palm oil as a feedstock for renewable energy. This should have been a warning for conservationists as France, the second-largest domestic producer of rapeseed oil, has seen dozens of native bird species decline up to 66%.

The threat of extinction in the EU due to agricultural activities is not confined to France. The environmental impact of pesticides on biodiversity had been pointed out by the Pesticide Action Network-Europe in its report from 2010. Renewed calls for the EU to act against pesticides have been ignored even as information links the decline of insects to the future of our planet.

Pesticide use in French agriculture ‘has meanwhile exploded’ over the past decade. But rather than address its accountability for biodiversity in member-states, the EU is extending the self-interest of its members by picking on imported commodities through de facto bans on these commodities, including the plan to phase out palm oil for biofuels.

The move was decried as discriminatory by palm oil producing countries and quite frankly, will prove to be an inconsequential move towards fighting climate change or protecting biodiversity in Southeast Asia.

The problem with the EU’s proposal to phase out palm oil as a biofuel is that a mere 4% of global palm oil production is used as EU biofuels. The European Parliament has grossly over-estimated its influence in protecting tropical forests in the top palm oil producing countries, Indonesia and Malaysia.

EU conundrum on imported rapeseed

Meanwhile, the focus of the EU on palm oil as a scapegoat for climate change and biodiversity is a dangerous distraction which should be blamed for the union’s failure to address both meaningfully.

The EU has only recently acknowledged that the popular replacement for palm oil, which is soybean, as having a devastating impact on diverse and carbon- rich regions in South America.

For example, one-fifth of EU soybean imports originate from razed forests in Brazil, where deforestation has risen to a 12-year high. Although the EU is slowly admitting that soybean imports must be scrutinised, it also plans to enact the controversial EU-Mercosur free trade pact which will heighten imports from the region.

The fact is, climate change and biodiversity do not hinge on single commodities. While it can be argued that soybean or palm oil producing countries face high rates of deforestation and biodiversity loss, the same can be said for other nations which produce vegetable oils.

If all vegetable oils were to be included in the EU’s assessment of biofuels for sustainability, the inclusion of rapeseed or its GMO version, canola, would drastically change the dynamics of these conversations.

For instance, Canada and the EU lead the world in rapeseed production. Both these nations, and countries like Australia which contribute 53% of EU rapeseed imports for biofuels, are encountering extreme rates of deforestation and biodiversity loss.

Australia, the only ‘developed’ nation to feature on WWF’s most recent deforestation report is also home to the ‘functionally extinct’ koala bear. According to conservationists, the iconic marsupial’s population is so low it cannot survive another generation in the wild. In Canada, a report detailing the threats of its endemic species highlighted that 40% of the 308 plants, animals and fungi are imperilled, with eight already extinct.

Ultimately, the EU’s phase-out of palm oil for biofuels will increase pressure on feedstocks, as the reliance on agricultural products like rapeseed accelerates biodiversity loss and emissions in countries at home and abroad.

Considering the call of the various bodies at the UN, it is encouraging to see the EU, as the global antagonist against palm oil as food and fuel, backpedal its position.

The EU-ASEAN Joint Working Group on Palm Oil seems to have agreed for the moment, that the environmental impact of all vegetable oil crops, whether for food or fuel or cattle feed, needs to be addressed in a global standard for sustainability. This approach is long overdue.

The latest statement from COCERAL, FEDIOL and FEFAC, which collectively represent EU grains and oilseed trades, nailed the historical problems on the head when they said: ‘Stigmatising and discriminating a specific commodity or origin has not shown so far to be effective for reducing deforestation. Complex situations cannot be tackled with oversimplification, false or inaccurate allegations.’

This fact should dominate the next discussion of the EU-ASEAN Joint Working Group. The livelihoods of French rapeseed farmers and those of oil palm farmers can hopefully be seen in a holistic context that includes birdlife in Europe and orangutan in Southeast Asia, as part of a global drive to fight climate change.

Robert Hii

Source: Global Policy Journal, March 15, 2021

This is a slightly edited version of the article, which is available at: https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/ 15/03/2021/case-global-sustainability-standards-vegetable-oils