Shift in focus?

July, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Sustainability

The release early in March of Greenpeace’s report ‘Certified: Destruction’, which was critical of the certification systems for forest and ecosystem risk commodities, has shifted the focus to the role of certification on the sustainability agenda.

The report had sought to ‘assess the effectiveness of (mainly voluntary) certification for land-based commodities as an instrument to address global deforestation, forest degradation and other ecosystem conversion and associated human rights abuses (including violations of indigenous rights and labour rights)’.

The certification schemes Greenpeace reviewed included the International Sustainability & Carbon Certification; Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance and UTZ; Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO); Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO); Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO); Roundtable for Responsible Soy; ProTerra, Forest Stewardship Council; and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification.

Greenpeace concluded that, while some certification schemes have strong standards, implementation has been weak, having failed to address deforestation and ecosystem destruction, and resulted in the ‘greenwashing’ of products.

‘The weaknesses and flaws identified in the certification schemes assessed in the report make it clear that certification should not be relied on to deliver change in the commodity sector. At best, it has a limited role to play as a supplement to more comprehensive and binding measures,’ it said.

Is Greenpeace throwing the baby out with the bathwater?

“The main conclusion of the Greenpeace report is that commodity-related sustainability certification schemes are not a solution to deforestation and forest degradation. Of course, ‘certification does not equal the definition of deforestation-free’ (to quote the report). It is not meant to be, as the certification schemes are intended to deliver holistically positive outcomes for people, planet and prosperity,” said Teoh Cheng Hai, senior adviser at Solidaridad Network Asia and founding secretary-general of the RSPO.

He added that voluntary sustainability standards such as the RSPO’s Principles & Criteria and national standards can contribute significantly towards the attainment of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, which include the preservation of forests and biodiversity and climate action.

Development of concepts

Global civil society organisation Solidaridad Network subscribes to the view that certification alone is insufficient to achieve sustainability goals. In a 2017 article, Honorary President Nicolaas Roozen had noted that many farmers and companies were already moving beyond certification towards more ambitious post-certification approaches, as the concept had turned out to be an expensive affair with low premiums that often did not reach farmers.

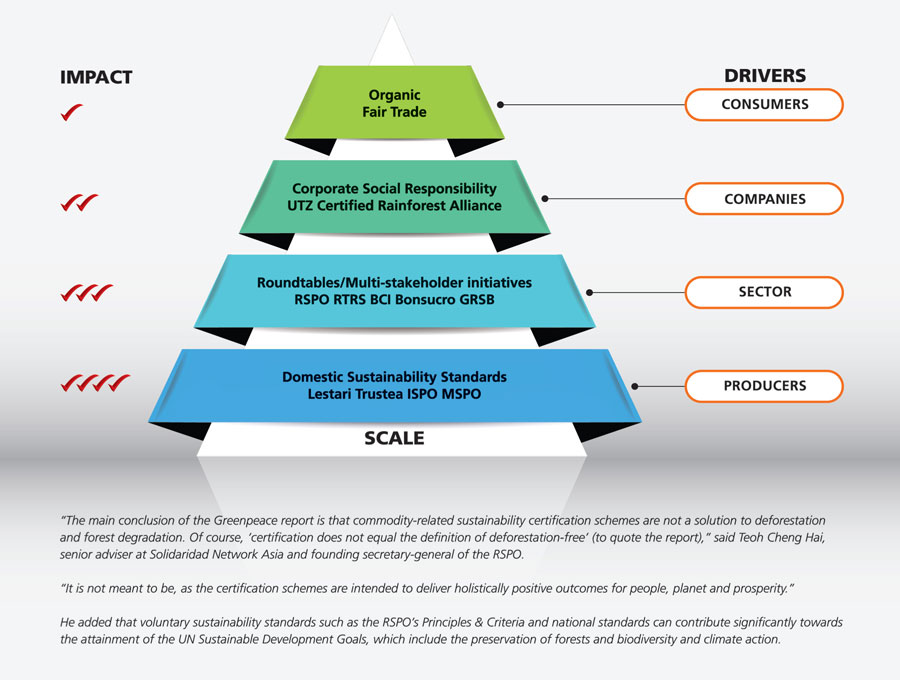

He explained that the sector-wide engagement process of certification – often called roundtables – is but one layer in the “pyramid of change” towards sustainability (see diagram).

The pyramid is a visual representation of the history of the certification process, which had started in the 1980s with consumers driving the demand for certification for organic products, followed by the fair trade system – initiated by Roozen – to improve terms of trade for farmers in developing countries. Both concepts were successful in raising awareness, but the market segments for fair trade and organic were limited at just 3-5%.

“From the perspective of transformative change in the sector, they didn’t make a difference … I think the main obstacle is, of course, the higher price for the consumer,” said Roozen.

Next came the corporate social responsibility (CSR) concept, driven by companies instead of consumers. Companies rebranded their products by adding a sustainable, social and ecological dimension to their marketing and sourcing. Examples include Rainforest Alliance and UTZ, which merged in 2017.

The third layer in the pyramid is the voluntary roundtable process involving sector-wide engagement, which saw the emergence of various roundtables for palm oil, soybean, beef and other commodities.

“The characteristic of a roundtable process is that the sector as a whole is engaged with a sustainability agenda and creates a platform for creating criteria and practices for sustainable sourcing and production. This is an even higher level of commitment and goes deeper into the supply chain [with] a sector commitment expressed by the relevant players of a specific supply chain,” Roozen explained.

“This concept of a roundtable, of stakeholder engagement, offers the opportunity to create scale because the big companies are on the table and are trying to improve and create better practices for the supply chain – not for a specific segment of the product but for the entire sector.”

At the bottom of the pyramid is the development of national standards (such as the MSPO and ISPO), which has made Roozen most excited, as it involves a commitment to sustainability by producer countries and producers.

“What started small scale with consumer preferences could expand its impact through the CSR and roundtable processes. My understanding is that the real change-maker that leads to transformative change is the national standard. Decisive for upscaling sustainability is local ownership and the commitment of local governments to transform the sector to move to more sustainable production, addressing domestic issues and challenges,” he said.

However, national standards are often seen as lower than Western standards.

To this, Roozen put forward Solidaridad’s twofold strategy of “raising the bar, raising the floor”, which is a smart mix of intervention. To illustrate, raising the bar here refers to extending support to smallholders to be included in the RSPO, while raising the floor refers to having the European Commission recognise the importance of national standards such as the ISPO and MSPO.

“One commitment for now is to switch from one-sided focus on the RSPO and give more value and importance to national standards, starting from these keywords. It starts with the recognition that, at the end, national governments have the authority, capacity and responsibility to address issues in their own sector. This is not a foreign agenda but a domestic one. It starts with the acknowledgment of the relevance of the national standards,” he added.

Furthermore, Europe’s imports of palm oil represent only 6% of global production and consumption, making it highly unlikely for this market to effect sector-wide transformation.

“The differentiator for successful transformation will be local ownership and engagement of the main – the most important – consumer countries. In the case of palm oil, they are India and China,” said Roozen, stressing that it is crucial to move from a Western-dominated agenda to local ownership and commitment, supported by demand for sustainable products in the global market.

Common agenda?

India and China are the world’s leading buyers of palm oil.

In 2020, India and China took up 31.4% of Malaysia’s palm oil exports. The EU followed in third place with 11.2%.

“If you don’t get a commitment from India and China to a sustainability agenda for palm oil production, then it’s a lost cause. That’s the way of thinking,” said Roozen.

The good news is, China and India are looking at the sustainability agenda.

India is the first country to recognise the MSPO as equivalent to sustainable, says Shatadru Chattopadhayay, Managing Director of Solidaridad Asia. The country has also set up the Indian Palm Oil Sustainability framework to create social, economic, environmental and agronomic guidelines for palm oil production and trade.

Similarly, interest in and awareness of sustainable palm oil is growing in China, not just because it buys a lot of the commodity but because of its investments in oil palm planting in Africa, said Teoh.

Apart from having national standards, there is also a need to rethink the earnings model of farmers as the way forward in upscaling sustainable agribusiness, said Roozen.

“What changes the world, if you look at the history of addressing social issues, is creating a business case for farmers that enables them to produce in a sustainable way and earn a living,” he said.

For example, the main driver of child and forced labour is the farmer’s inability to afford higher cost of labour.

“If you change the earnings model, he can have better return and income, he can have mechanisation and replace child labour with machinery and technology.”

In changing the perception of palm oil, Roozen said producers and naysayers must define a common agenda, starting with two statements. First, the contribution of the palm oil sector in eliminating poverty. And second, the commodity’s relevance as an affordable cooking oil for the poorest segments of consumers, owing to its high levels of productivity.

“Greenpeace has never made those statements … On those two basic elements, you can define a common agenda. Otherwise, you will always have discussions that are fruitless and will not connect people to address a common agenda,” he added.

Source: The Edge Malaysia Weekly,

March 29 – April 4, 2021