... for potential fertiliser disruptions

May, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Markets

Brazil is a powerhouse agricultural producer, ranking among the top three global exporters for a host of commodities. To support its massive agribusiness sector, Brazil relies on imported inputs, including fertilisers. Annually, Brazil imports over 80% of its total fertiliser needs. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has substantially elevated the risk of disruption to the global fertiliser trade. In Brazil, there is rising concern that growers may not be able to expand the crop planted area in the 2022/23 season.

Without critical nutrients such as potash, Brazil will also see lower crop yields. In recent months, Brazil has engaged in international diplomacy, striking deals with Iran and Russia to maintain fertiliser flows.

To reduce the sector’s dependence on imports, the government has also developed a National Fertiliser Plan, though the implementation is expected to take decades.

Brazil is a powerhouse agricultural producer, ranking among the top three global exporters for such crops as soybean, corn and sugar, as well as beef and chicken. To support its massive agribusiness sector, Brazil relies on imported inputs from machinery to agricultural chemicals. The dependence on imported inputs is most acute for fertilisers. Annually, Brazil imports 85% of its total fertiliser needs. More than 70% of all fertilisers are used in the cultivation of three crops: soybean (44%), corn (1%) and sugar cane (11%).

Over the last several months, there has been increasing concern not only about the rising fertiliser prices but also potential disruption to the global fertiliser trade. The disruption in global fertiliser supply is associated with a host of reasons: production bottlenecks owing to the Covid-19 pandemic, protectionist trade measures by important producers, as well as geopolitical tensions. The potential risk of fertiliser disruption to Brazil rose substantially with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Russia is a leading global supplier of fertilisers, and Brazil sources about a quarter of its fertilisers from Russia.

Fertiliser requirements and strategy

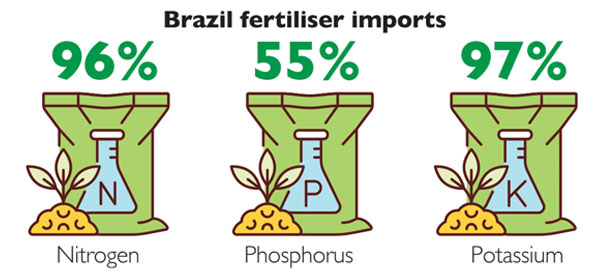

The main commercial fertilisers are derived from the so-called ‘big 3’ primary nutrients: nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P) and potassium (K). Taken together, they are known as NPK formulas. The modern agricultural practice uses these primary nutrients in large amounts plus secondary macronutrients: Calcium, Magnesium and Sulfur; and micronutrients: Boron, Chlorine, Copper, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Zinc, Cobalt, Silicon and other elements to ensure plant health and proper maturation. Brazil imports almost 96% of its nitrogen, 55% of its phosphorus and 97% of its potassium. In the event of disruption to trade, the Brazilian growers point to potassium as being the most problematic to source.

On March 11, 2022, the Government of Brazil (GoB) unveiled the National Fertiliser Plan, designed to decrease the country’s dependency on NPK imports. The Geological Survey of Brazil prepared several scenarios to reduce the national dependency on imports to 60% by 2050. The main thrust of the strategy is to attract private investment into the sector. The local media indicate that Brazil intends to bring the strategy to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development to discuss ways of attracting international and national investors to Brazil’s domestic fertiliser market.

Recognising that import needs will remain substantial even in the long term, the GoB has cultivated partnerships with key suppliers of fertilisers: Canada, China, Morocco, Russia and Belarus among others. In February 2022, high-placed Brazilian officials visited Russia and Iran, striking deals to keep fertiliser supplies flowing. However, the risk of force majeure to these contracts remains. According to Brazilian press sources, Minister Tereza Cristina stated on March 3 that fertiliser trade with Russia has been suspended as Brazil “has no way to pay for products, nor ships to load. As long as there is war, the possibility of receiving fertilisers is totally ruled out.”

NITROGEN: Essential for the formation of protein, nitrogen is considered the most crucial of the big 3 nutrients

Raw materials and production: Natural gas is the main ingredient required to make nitrogen fertiliser. In several transformation steps, hydrogen from natural gas is mixed with nitrogen from the air to form ammonia, an intermediate product. Ammonia is then further processed into two main end products – ammonium nitrate and urea. Different fertiliser types can be manufactured by further mixing nitrogen-derived substances with other nutrients.

Trade: Brazil imports 96% of its nitrogen fertiliser needs. It sources almost 100% of its nitrogen fertiliser from Russia. Brazil sources both the intermediate product ammonia, as well as end products ammonium nitrates and urea.

Ammonia: At roughly 4.5 million tons shipped, Russia accounts for around 24% of global ammonia exports as of 2020. Many other countries produce ammonia, and market analysts generally anticipate that any disruption to shipments of ammonia from Russia will be easily substituted by other markets.

Ammonium nitrate: Russian exports various grades of ammonium nitrate and accounts for around 40% of all global nitrate trade as of 2020. Of that volume, roughly half was shipped to Brazil. Russia is Brazil’s only supplier of ammonium nitrate. However, nitrates are also produced in Europe, the US and China. As Brazil is in Southern Hemisphere, the different seasonality from Europe and the US may allow it to take advantage of the global nitrate capacity outside peak application timeframes of the Northern Hemisphere.

Urea: Russia supplies 21% of Brazil’s urea imports. However, Brazil does have alternative suppliers. Urea is commonly produced and exported by various countries in Africa, the US, as well as by Russia. In its National Fertiliser Strategy, Brazil identified the US as a potential source for ammonia and urea imports.

Domestic capacity: According to the Brazilian press coverage of the 2022 National Fertiliser Plan, operating at full installed capacity, Brazil’s local nitrogen fertiliser production could meet 17.6% of the country’s current consumption needs. The actual production is much lower. In 2020, Brazil produced 224,000 tons of nitrogen fertilisers, an amount that could meet just over 4% of the country ́s demand in the same year. Brazil currently has three operational nitrogen units:

National Fertiliser Plan: Natural gas prices are a major factor in enabling the production of ammonia and urea. Brazil will also need upfront investment to expand the number of nitrogen-producing plants and their capacity. Brazil intends to increase nitrogen installed capacity up to 2.8 million tons by 2050.

To reach that volume, the GoB plans to attract at least two more nitrogen producers to Brazil by 2030, and another four by 2050. The government seeks to attract at least $10 billion to increase nitrogen production and output of raw materials by 2030, and the same amount each decade by 2050.

PHOSPHORUS: Facilitates photosynthesis, which enables the plant to use and store energy

Raw materials and production: Phosphorus-based fertilisers are produced from mined ores. Phosphate rock is primarily treated with sulfuric acid to produce phosphoric acid, which is either concentrated or mixed with ammonia to make a range of phosphate (P2O5) fertilisers.

Trade: Along with Morocco and China, Russia is a key global provider of phosphates. Russia accounts for around 17% of the total global trade in finished phosphate fertilisers. Russia is also the largest global producer and supplier of high-grade igneous phosphate rock. Brazil is the single largest buyer of phosphate fertilisers from Russia. Any interruption of the exports of phosphate rock from Russia would have an immediate and significant impact on especially European fertiliser production. The result would drive up global scarcity and prices of phosphate fertilisers.

Domestic capacity: Currently Brazil has five phosphate fertiliser producers.

National Fertiliser Plan: By 2030, the government envisions at least five auctions of mining areas for phosphate fertilisers. The National Strategy also outlines plans for an addition of two phosphate fertilisers and raw materials producers in new mining areas by 2030, totaling seven producers and increasing that number to 10 by 2040. The goal is to increase phosphate rock exploration by 3% each year through 2030, and by 2% each year until 2050. Brazil intends to enhance its phosphate rock production to reach 27 million tons per year by 2050.

POTASSIUM: Strengthens root systems, helping plants resist disease, cold and dry weather; potassium increases crops’ quality and yields

Raw materials and production: As is the case with phosphorous, potassium-based fertilisers are produced from mined ores. Several chemical processes can be used to convert the potassium rock into plant food, potassium chloride, sulfate and nitrate. Potash is sourced from various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water-soluble form.

Trade: Brazil imports over 11 million tons of potash annually, of which 5.5 million tons come from Belarus and Russia. Contacts note that disruption to potash imports would be the most problematic, as the top suppliers account for the majority of the global market.

Global trade in potash is very concentrated; Canada is the world’s leading exporter of potash, with a roughly 20% market share. Together, Russia and Belarus account for about a third of global potash exports. Notably, Belarus is already subjected to sanctions on its potash exports. Thus, any disruption to Russian potash shipments would have a significant effect on the global availability of potash. Market estimates are that global shortfall would be on the order of 30% and would not be made up from other sources.

Domestic capacity: Brazil’s main potash deposits with exploration potential mapped so far are located in Sergipe and Amazonas states and account for around 3% of global deposits. Brazil has only one potash producing unit, in Sergipe state, owned by Mosaic Fertilizantes; its production reached around 9.5 million tons in 2020.

National Fertiliser Plan: By 2030, the government wants to enable at least five auctions of mining areas of potassium fertilisers. Brazil aims to raise national production gradually through 2050 to 6 million tons of installed capacity. To reach that volume, the goal is to double to 10 the amount of potash and raw materials producers by 2030, adding another 10 producers by 2040.

United States Department of Agriculture,

Foreign Agriculture Service

This article is available, at:

https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Brazil%20Agriculture%20Seeks%20Remedies%20for%20Potential%20Fertiliser%20Disruptions_Brasilia_Brazil_BR2022-0017.pdf