By tracking jurisdictional sustainability

March, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Sustainability

The palm oil industry has become a major contributor to the economies of Indonesia and Malaysia over the past few years. In Indonesia alone, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics, 48.4 million tonnes of palm oil were produced in 2019, approximately 60% of the world’s supply. More than 60% of the palm oil was exported, valued at almost US$16 billion.

Further, according to the Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs, the expansion of oil palm plantations has helped lift more than 10 million Indonesians out of poverty since 2000. The industry supported the livelihoods of 23 million people in 2018, 4.6 million of whom are involved in independent smallholdings across the country.

However, along with other agricultural commodities, such as rubber, soybean, coffee and cocoa, palm oil production has been linked to legal and illegal deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss, greenhouse gas emissions, and violations of labour and community rights. Consuming countries as importers of ‘forest risk commodities’ have frequently been held responsible for driving these impacts and for importing deforestation through commodity supply chains.

Stakeholders along the supply chain have responded via various means, including through policy measures to reduce deforestation, forest degradation and associated emissions. As an example, through its second Renewable Energy Directive (RED II), the European Union (EU) plans to phase out eligibility of biofuel feedstock to EU renewable energy targets where they are assessed to be the cause of high indirect land use change.

Palm oil is currently classified in this category and since around half of the EU’s palm oil imports are for biofuel, the regulation could affect a significant proportion of palm oil exports to the EU from Indonesia. The Indonesian government is currently challenging the RED II in the World Trade Organisation.

Indeed, in recent years, importing countries, consumers and NGOs have been pressuring palm oil companies and producing countries, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, to step up their sustainability game. Many stakeholders have responded with efforts to show that a sustainable palm oil industry, which provides win-win outcomes for markets and the environment, is not only possible but also constitutes the ambition moving forward.

The Indonesian government, for example, has accelerated the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification in the past couple of years. In addition, the government has issued a national action plan for sustainable palm oil and adopted a moratorium policy banning new expansion of oil palm plantations. Based on an analysis by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Indonesia’s total deforestation fell by 20% following the launch of the moratorium policy in 2011.

Subnational jurisdictions at the forefront

In Indonesia, some subnational governments have been very active in supporting the national government’s policies on sustainable palm oil. According to the Civil Society Coalition for Improving Palm Oil Governance, up to December 2019, six provinces and eight districts have responded positively to the national government’s policies by issuing bylaws or making public commitments about the moratorium.

A few subnational governments have also been embracing the jurisdictional approach, which seeks to address palm oil and deforestation related issues at the subnational level by involving all relevant stakeholders. For example, Seruyan District in Central Kalimantan is working with the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to ensure all palm oil producers in the district comply with RSPO Principles & Criteria.

This approach is also pursued by the state of Sabah in Malaysia, which aims to be 100% RSPO certified by 2025. In East Kalimantan, the Berau District Government is collaborating with the Nature Conservancy, Climate Policy Initiative, and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit on a low-emission oil palm development programme. In North Sumatra, the South Tapanuli District Government is collaborating with the United Nations Development Programme and Conservation International Indonesia to form a multi-stakeholder forum on sustainable palm oil.

These subnational initiatives, led by the provincial/state and district-level governments, hinge on the role local governments can play given their authority and legitimacy to promulgate regulations and policies for sustainability. The subnational governments, for example, have the authority to issue certain permits on the use of land and establishment of plantations, and to monitor and enforce laws and regulations underpinning the transition of the entire jurisdiction towards sustainability.

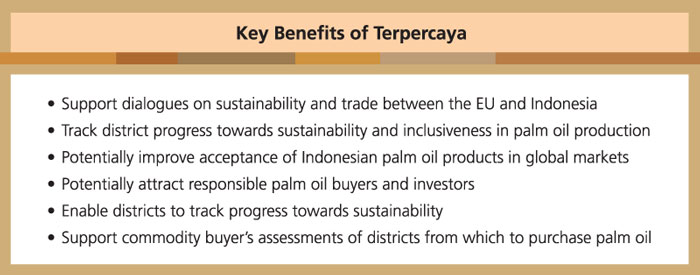

Further, the subnational initiatives can potentially bring in multiple benefits – not only by attracting palm oil buyers and investors who care about sustainability, but also by supporting national and subnational governments in making progress towards development targets and international commitments, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement.

Tracking jurisdictional sustainability

With support from the EU, the Indonesian Ministry of National Development Planning (Bappenas), which coordinates the planning and monitoring of the nation’s development and SDG implementation, is spearheading an initiative to implement a framework to monitor and measure the performance of districts in achieving national priorities and the SDGs.

The framework resulted from an initial 2018-19 study, led by the European Forest Institute (EFI) and the Indonesian NGO Inobu, which assessed the feasibility of mapping and screening Indonesian districts based on their commitment and performance regarding sustainability of forest and agricultural production, especially palm oil.

The framework, known as the Terpercaya approach, takes its name from an Indonesian word meaning ‘trustworthy’, as it aims to generate objective and transparent information and analysis. Through a collaborative process involving the multi-stakeholder Terpercaya Advisory Committee, composed of the government, private sector and civil society stakeholders, the initial Terpercaya study developed 22 indicators.

The indicators, covering environmental, social, economic and governance aspects, are based on Indonesian laws and regulations, aligned with national priorities and the SDGs, and supportive of the national policies to promote a sustainable palm oil industry, such as the ISPO standard.

By covering entire districts, the Terpercaya approach should help create a level playing field for all producers, including certified and non-certified actors, companies with and without sustainability commitments, and smallholders of all types.

The approach will be particularly advantageous to smallholders, as it provides them with the chance to better access the markets for sustainably produced palm oil. At a broader scale, the Terpercaya approach should also assist the districts’ efforts to increase competitiveness and attract sustainable, green investment.

Terpercaya data platform

In 2020, Bappenas, EFI, Inobu and several other partner organisations collected data for the 22 agreed indicators and established a national database containing information on the sustainability of Indonesian districts.

A user-friendly public Terpercaya data platform showcasing this information will be launched soon. It will monitor and measure sustainability progress against baseline data and allow users to compare district progress in various dimensions of sustainability. Linking the platform to supply chain information to help commodity buyers assess districts from which they are purchasing palm oil will also be possible.

The platform will benefit different users. At the subnational level, the platform will enable district authorities to track progress towards sustainability and inclusiveness in palm oil production. For example, it could encourage district authorities to resolve land tenure issues and accelerate ISPO certification for smallholders, thus complementing existing commodity-based certification systems.

At the same time, the central government can use the monitoring system to programme incentives and support for local governments to achieve sustainable and inclusive agricultural development and SDGs. In this context, Bappenas plans to use the Terpercaya framework to guide fiscal transfers to districts under the special allocation fund for agriculture.

Further, the Terpercaya platform could help improve acceptance of Indonesian palm oil products in global markets and ensure that civil society, consumer countries, investors and commodity buyers are well informed about the progress made by Indonesian districts. The Terpercaya platform could also serve to contribute to constructive and open dialogue.

The Terpercaya platform could additionally support the private sector in meeting their sustainability commitments. For example, international buyers of palm oil and investors could use the information presented in their sustainability due diligence assessment, to help determine with which districts to interact.

At its core, the Terpercaya approach aims to help resolve trade-offs between palm oil production and environmental protection by promoting market access for sustainable palm oil, utilising government capacity, and supporting broad-scale achievement of national priorities and internationally agreed SDGs.

The approach’s unique selling points include the objective information it showcases, the collaborative development of indicators, and its alignment with the national context, especially the existing policy and legal frameworks. In principle, such an approach could be easily implemented in countries other than Indonesia.

For now, the primary focus is to build a larger and stronger collaboration around Terpercaya, involving a broader range of stakeholders in Indonesia and beyond. This is needed to ensure that the approach reaches its maximum potential in advancing sustainability in the palm oil industry and maintaining benefits from production and trade of a valuable commodity.

In this context, the recently initiated EU-funded Keberlanjutan sAwit Malaysia dan Indonesia (KAMI) or ‘sustainability of Malaysian and Indonesian palm oil’ project aims to support policy dialogue between relevant stakeholders in the EU, Indonesia and Malaysia on the sustainable use of palm oil.

The project also encompasses support for collection and dissemination of agreed, objective information on subnational level sustainability performance to reinforce dialogue and better communicate on the production of palm oil.

Through KAMI, support for Terpercaya will continue and experience gained over past years will be built upon in developing jurisdictional indicators of sustainability performance aligned to EU policy. Through collection and dissemination of associated information, Terpercaya will transition from a national to an international approach.

Satrio Wicaksono

Forest and Land Use Governance Expert, EFI

Anang Noegroho

Director of Food and Agriculture

Ministry of National Development Planning, Indonesia

Silvia Irawan

Executive Director, Inobu

Josi Khatarina

Senior Advisor, Inobu

Jeremy Broadhead

KAMI Project Manager, EFI