The progress of global food security hinges on the ability of the farming community to efficiently produce sufficient and nutritious food to satisfy needs. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has sounded the early warning that the agri-food sector would need to generate 50% more food by 2050 to meet demand.

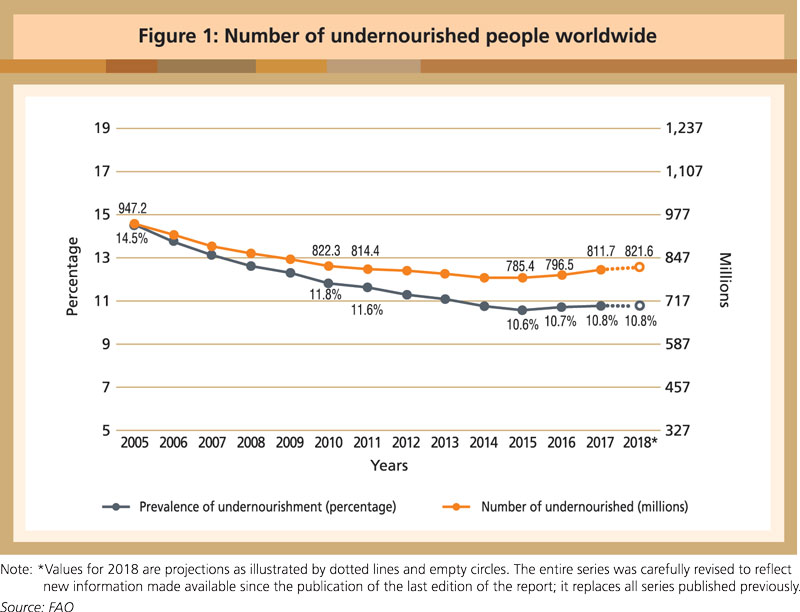

Food security is a serious threat facing millions of households in developing countries. The number of people suffering from hunger over the past three years has increased to more than 820 million – one in every nine people in the world (Figure 1).

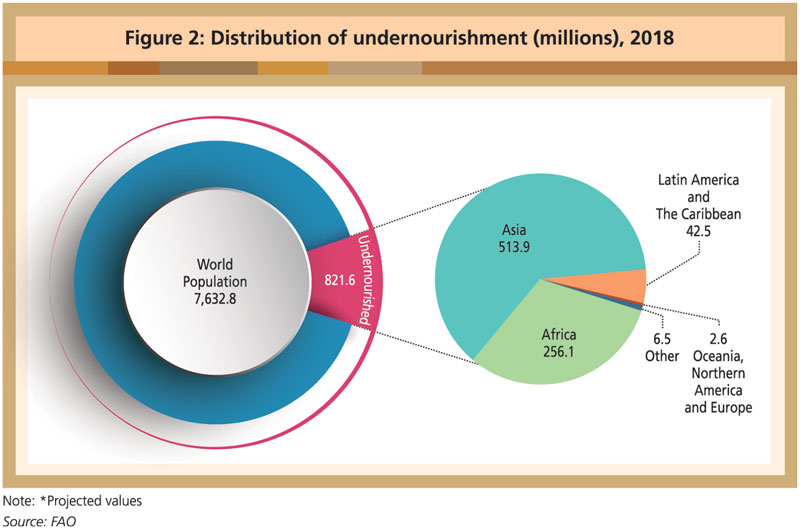

More than 50% of the undernourished live in Asia, while more than 30% live in Africa (Figure 2). These are regions with high potential for agriculture expansion for plantation crops like the oil palm that could easily help to reduce poverty, hunger and unemployment.

Palm oil offers an ideal solution for both global food insecurity and sustainable agriculture. In stepping up food production, however, growers now have to contend with climate change issues and complaints of environmental degradation.

Challenges have emerged from Green activism in Europe. These range from hostility towards farmers to environmental policies that ban the use of pesticides like glyphosate to support nature-based solutions. Animal welfare groups championing a vegan lifestyle have led protests in Germany, France, the Netherlands and Ireland.

Public opinion has come to play a role in the debate on palm oil issues in the EU. The just-released European ‘Green New Deal’ (see Box), announced by European Commission (EC) President Ursula von der Leyen, provides a roadmap of action for all sectors of the economy – notably transport, energy, agriculture and buildings – as well as industries such as steel, cement, ICT, textiles and chemicals.

She has been quoted as saying that the EC will propose a law in March that would “make the transition to climate neutrality irreversible”, adding that the measure will extend the scope of emissions trading and will include “a farm-to-fork strategy and a biodiversity strategy”. One of the proposals is to penalise imports from countries with lower emissions controls.

The Environment, Public Health and Food Safety Committee – the largest in the European Parliament – has approved a resolution calling on the EU to enact a long-term strategy to reach climate neutrality by 2050.

The EU Delegated Act which came into effect on June 10, 2019, restricts the types of biofuels that may be counted toward renewable energy goals, and introduces a certification system. Palm oil biofuel has been categorised as ‘high’ risk under the Act, due to alleged indirect land-use change (ILUC) factors, loss of biodiversity and greenhouse gas emissions. It is the only feedstock categorised as ‘high risk’. Its use in transport fuel will be phased out by 2030, and it will not be eligible to receive incentives from EU member-states.

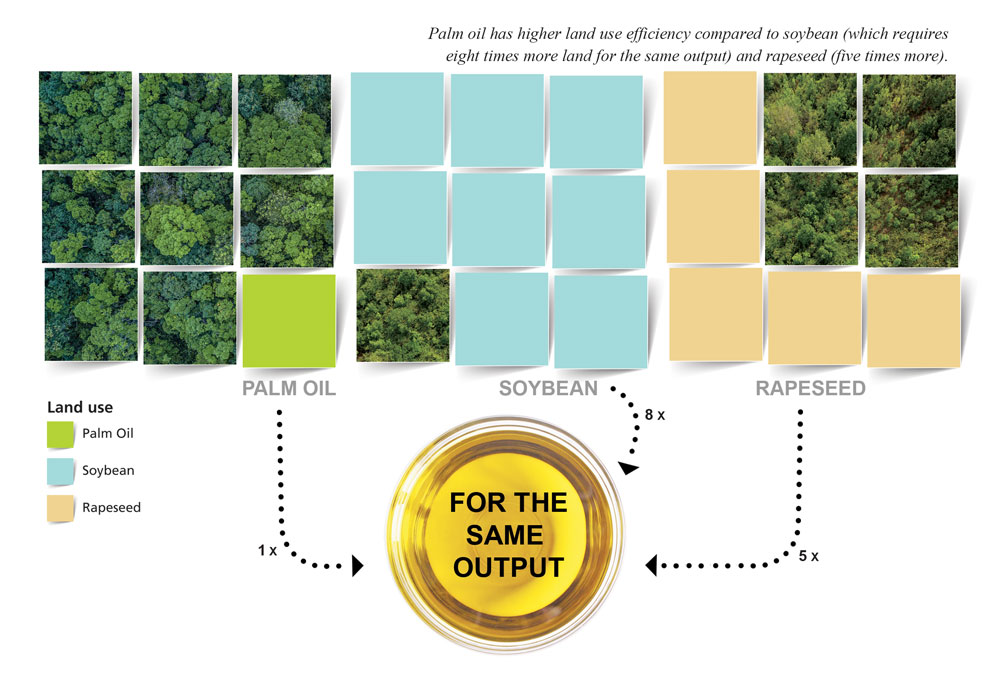

The EU ban on palm oil biofuel will only increase the production of low-yield, less efficient crops. Palm oil has higher land use efficiency compared to soybean (which requires eight times more land for the same output) and rapeseed (five times more).

According to LMC International, if all oil palm expansion were to be stopped, 150 million ha more land would be needed for soybean to meet the supply gap for vegetable oil. This would be more than four times the entire area under oil palm in 2030.

The EU’s protectionist measure has compelled Indonesia and Malaysia, the two largest palm oil producers, to act. Indonesia took the first step by filing a complaint with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) on Dec 15, 2019.

However, the system to settling disputes may not be able to play an effective role. It has been reported that Washington has blocked the WTO from appointing members to a dispute panel over the past two years, impacting the future of the appellate body. This would mean disputes will remain unresolved, especially to the detriment of the interests of trade-reliant nations.

As an alternative strategy, Malaysia could consider measures similar to that in Iowa in the US, where the Governor signed an executive order. This requires all new contracts for state-owned diesel vehicles to be purchased from engine manufacturers that can accommodate at least 20% biodiesel. Such a move would support Malaysian oil palm farmers, as well as the renewable fuels sector.

Levels of food insecurity

Farmers are a critical component in ensuring food security, food health and food sustainability. If they are unable to meet the demand for food, prices will increase. Consumers would then have to settle for lower quantity and quality of food, which would make them vulnerable to undernourishment.

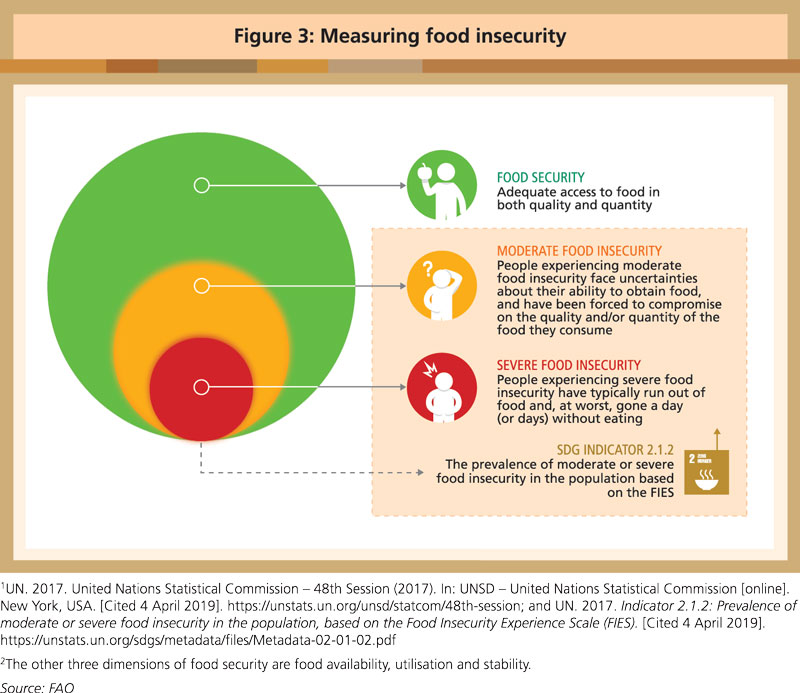

The FAO’s Food Security and Nutrition in The World 2019 report has distinguished various levels of food security (Figure 3). Moderate food insecurity occurs when people face uncertainties about their ability to obtain food and have been forced to reduce, at times during the year, the quality and/or quantity of food they consume due to lack of money or other resources.

Severe food insecurity affects a community or nation when people have likely run out of food, experienced hunger and, at the most extreme, gone for days without eating, putting their health and well-being at grave risk.

Additional factors that affect malnutrition are economic slowdowns and downturns; world price fluctuations for countries dependent on production of primary commodities; and the ability to trade in free and open markets. The consequences are unemployment and low income, leading to an impact on food intake.

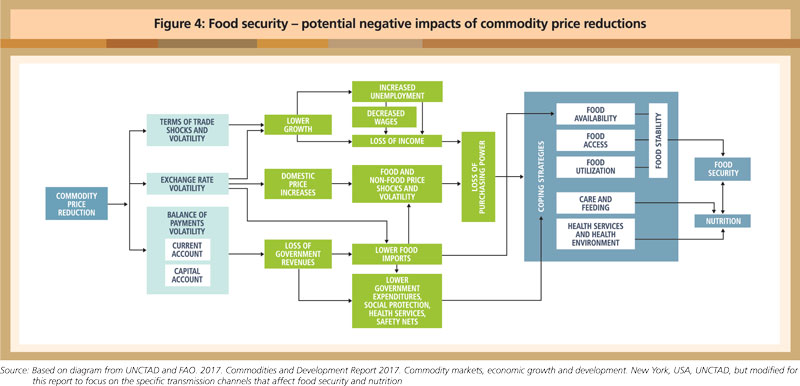

Countries dependent on primary commodity exports, such as in South America, Asia and Africa, already know this. Low commodity prices may result in depreciation and devaluation of currencies resulting in domestic price increases, including food prices (Figure 4). This then affects the ability of households to buy food, as the cost increases relative to their incomes.

Added to this are direct and indirect impacts associated with fluctuations in commodity prices. The direct impacts affect terms of trade, exchange rate adjustments and the balance of payments. The indirect effects impact domestic prices, including that of food, as well as employment, wages and provision of health and social services.

Belvinder Sron

Deputy CEO, MPOC

The European Green New Deal

What is the Green New Deal?

On Dec 11, 2019, the European Union (EU) launched its ‘Green New Deal’ policy strategy consisting of some 50 proposals. These include a legally binding target of reducing EU emissions to net zero by 2050; a carbon border tax to prevent companies from relocating outside the EU to avoid climate legislation; a €100 billion just transition fund to help industries transition; and a policy to not conclude any free trade agreement with a country that is not a signatory to the Paris climate agreement.

What can we expect from the Green New Deal?

Incoming European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen aims to put forward the concrete proposals for implementation of the Green New Deal within the first 100 days of the new Commission’s mandate.

This will include:

Source: MPOC