Like many other commodities, palm oil experienced high prices throughout 2021. Prices more than doubled over the past 18 months to a record high of US$1,213.85 a tonne in October 2021. In November and December, however, prices dipped and weighed on 2021’s average pricing to US$1,000 per tonne.

The high prices can be arguably attributed to lower palm oil output. For most of 2020 and throughout 2021, Covid-19 pandemic-led border closures had starved Malaysia’s oil palm estates of many foreign workers who had returned home and could not re-enter the country.

The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) also sees structural changes in the global palm oil supply due to a slowdown in new plantings throughout Indonesia and Malaysia since 2015. With the ageing tree profile across both countries, the replanting programme will also temporarily limit palm oil supply in the short to medium term.

As agricultural land becomes limited, oil palm replanting is key to boosting palm oil yield across Indonesia and Malaysia. It is important to replant to sustain supply because these countries produce about 85% of the world’s palm oil needs. LMC International highlights that the global palm oil supply will only see minimal growth in the 2019-22 period due to year-end floods and the labour shortage in Malaysia.

On the other side of the globe, severe drought at Canada’s farmlands in 2021 resulted in its smallest rapeseed harvest in 13 years. The lower-than-expected supply of soft oils induced the sharp rise in other vegetable oil prices to a 10-year high, which then had a spillover effect onto palm oil pricing. The limited supply of vegetable oils all over the world is likely to continue into the first half of this year.

Production outlook

Palm oil production in Indonesia was 6.7% higher in the second quarter of 2021, gathering pace from the 1.5% growth in the first quarter and spurred by better rainfall in 2020. Output in the third quarter of 2021, however, was slightly curbed by floods in Kalimantan, which disrupted oil palm fruit harvesting. In the fourth quarter, the Indonesian Palm Oil Association (GAPKI) announced that production had fallen further. Its initial forecast of a better harvest in the second half of 2021 than the first, did not materialise. So, for the full year, GAPKI has revised its palm oil output forecast to 46.6 million tonnes, down 0.9% from 2020.

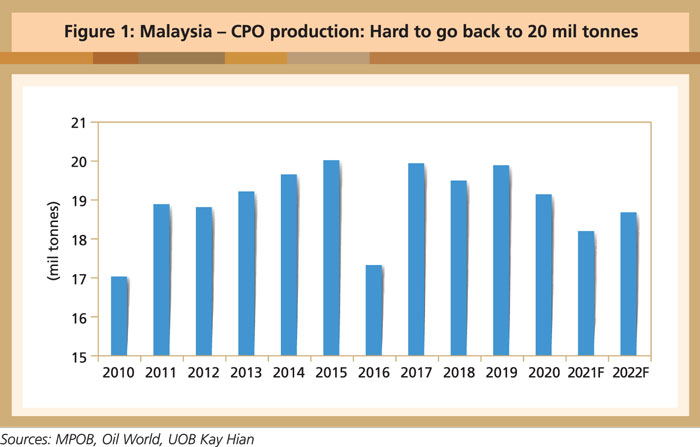

The Malaysian Palm Oil Board estimates that Malaysia’s 2021 palm oil output will drop to 18.3 million tonnes from 19.2 million tonnes in 2020. Palm oil ending stocks are expected to stay at below-average levels of 4 million tonnes in Indonesia and 2.1 million tonnes in Malaysia.

This year, Indonesian palm oil output is expected to recover due to good estate management and no halt of operations, supported by the absence of a La Nina impact. This, however, is not the case for Malaysia. Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, foreign workers who account for about 75% of the 500,000 harvesters employed on Malaysian oil palm estates have not been able to return due to border restrictions. Analysts forecast that Malaysia’s plan to bring in 32,000 foreign workers will only likely materialise towards March. The signing in December 2021 of a five-year memorandum of understanding between the governments of Malaysia and Bangladesh to hire more workers is a step in the right direction.

The second challenge is the high cost of fertiliser. Small farmers are expected to reduce fertiliser applications due to sharply increased prices, potentially reducing future output. Fertiliser and pesticide prices have surged significantly due to supply chain disruptions, higher demand, rising freight charges and input costs. The price of fertilisers, such as nitrogen and phosphate, has risen by 50-80% since mid-2021, while the price of herbicides, such as glyphosate and glufosinate, has more than doubled due to supply chain disruptions and more expensive raw materials.

It is also becoming difficult to obtain supplies. Thus, the oil palm sector may again suffer from low fertiliser applications this year. The cost of fertiliser is a major component after labour for oil palm growers, making up about 30-35% of the ex-mill costs. Companies will continue to feed oil palm trees this nutrient despite the high price, but may not receive the volume ordered due to supply constraints and uncertain shipment arrangements. Planters are highly dependent on imported fertilisers, but those in Indonesia have an advantage as local urea production is sufficient to meet domestic demand.

Based on industry sources, the estimated fertiliser imports for 2021 are 60-65% of the usual annual requirements. As the logistics bottleneck is unlikely to ease any time soon, 2022 could see even lower fertiliser imports. Smallholders may again be tempted to give less fertiliser to trees. The impact of reduced fertiliser usage in 2018 and 2019 still shows today, as yield recovery is weaker than normal. As a result, Indonesia and Malaysia may not be able to deliver much output growth in 2022.

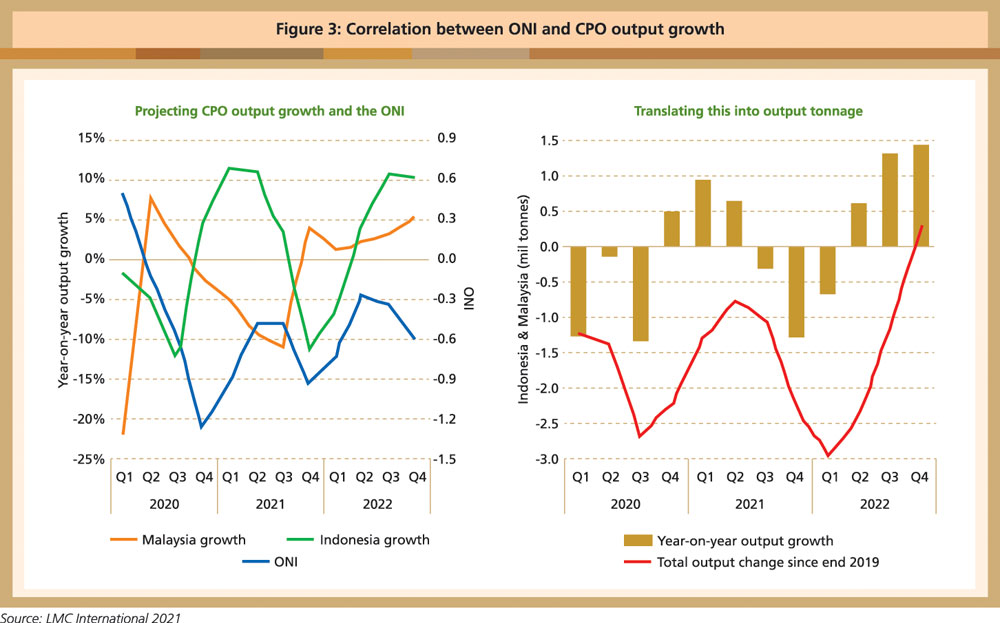

LMC International reports that Indonesia and Malaysia are in a long La Nina period in which the Oceanic Nino Index (ONI) is more negative than -0.5. The pattern of the ONI curve since 2020 echoes that of 2010-11, with La Nina weakening and then returning. If 2012 is taken as a guide, La Nina should end in 2022. A rising ONI is correlated with rising output growth, and a falling ONI is linked to slowing output growth. This is especially true for Indonesian production.

El Nino is a phenomenon of dry conditions for harvesting with the benefit of the previous year’s rains. With La Nina, there will be twin blows from heavy rainfall at estates and El Nino drought in the following years. In view of the apparent link between the ONI and output growth, in Indonesia, LMC International predicts that there will not be much palm oil production growth in 2022. The US National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration predicts a 95% chance of a weak La Nina lasting through February 2022.

Demand outlook

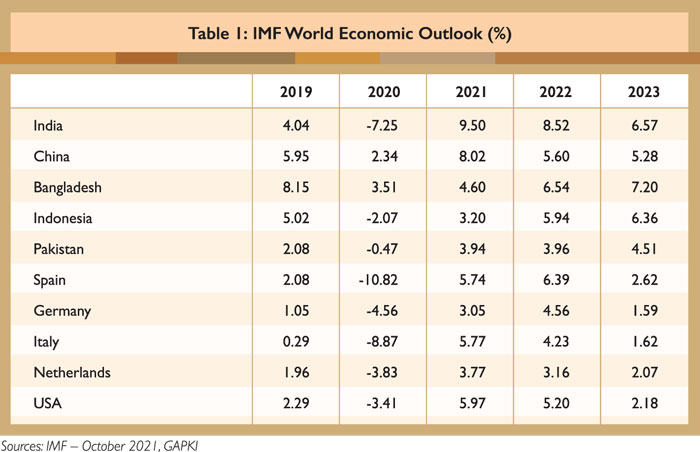

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its World Economic Outlook estimates that the global economy grew 5.9% in 2021 and will expand by 4.9% in 2022. The economic outlook will continue to be positive (Table 1).

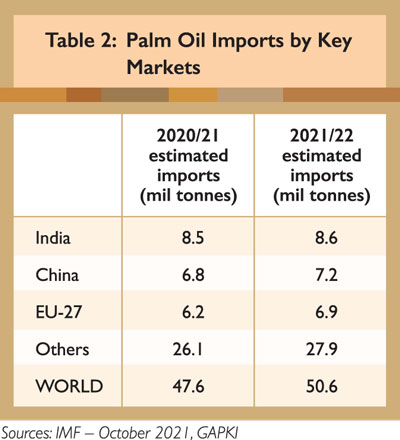

According to Refinitiv Agricultural Research, global palm oil demand for 2021/22 is forecast at 50.6 million tonnes, up 6.5 % compared to the prior season (Table 2), provided there is no large-scale demand destruction.

India’s palm oil purchases this year are estimated at 8.6 million tonnes in 2021/22. The slight increase is boosted by the reopening of business activities, multiple import tax cuts and lifting of import restrictions on RBD palm olein. However, the upside to higher palm oil imports is limited by its narrowing discount to soybean oil and sunflower oil.

Also, the Indian government implemented stock limits on edible oils in October 2021, regulating the stocks that retailers and wholesalers can carry. Despite higher domestic oilseed supplies (including soybean, rapeseed and groundnut) on the back of ample rainfall and planted area expansion, crushing activities have not kept up. So, lower domestic vegetable oil production may potentially prompt higher palm oil imports.

China is the world’s second-largest buyer of palm oil after India and imports about 6-7 million tonnes from Indonesia and Malaysia every year. This year, China’s palm oil consumption is expected to increase due to a lower supply of rapeseed oil and soybean oil. It is also seen to buy more palm oil products for animal feed.

China’s palm oil imports are expected to rise to 7.2 million tonnes in 2021/22 boosted by economic recovery. There were more shipments to China ahead of the Lunar New Year and Winter Olympics in February. However, the upside could be limited in the months ahead by recent higher soybean crushing activities amid better crushing margins, which will lead to higher domestic soybean oil supplies. Also, RBD palm olein’s discounts on soybean oil have been narrowing, thus potentially dulling consumer buying interests.

Exports to the EU are expected to be muted, partly due to unattractive palm oil prices for biodiesel blending and early implementation of the revised Renewable Energy Directive by some member-states. The European Commission’s proposed law and due diligence to require proof that agricultural imports are not linked to deforestation, could potentially dampen palm oil sentiment.

The EU-27 palm oil imports are estimated at 6.9 million tonnes in 2021/22. Although the reopening of economies and the competitive prices of palm oil versus other edible oils will likely increase overall demand in 2021/22, renewed lockdowns – following the discovery of the Omicron variant of the Covid-19 virus – have raised doubts. The impact on palm oil demand is unclear at this point.

Price outlook

Industry experts forecast a tight stock situation and higher prices to run into the first half of 2022. Key factors to watch are the pace at which foreign workers are allowed to return to Malaysia; the impact of massive floods at many oil palm estates in five states across Malaysia; high costs of fertiliser; and the impact of the Omicron variant on production recovery.

At the Indonesian Palm Oil Conference in December 2021, many market analysts forecast that palm oil prices would remain firm, supported by a limited vegetable oil supply in the first half of 2022. However, they differed as to when and how much the prices would fluctuate throughout the year.

LMC International indicates that tight supplies of palm oil, rapeseed oil and soybean oil have fueled the current high palm oil price. It cautioned that palm oil prices may be moderated by rising interest rates and hesitancy by major biodiesel users. It also predicted that there would be a small drop in the Crude Palm Oil-Brent premium until all vegetable oil output recovers in the second half of 2022. The key potential bullish factors that will keep prices higher are weather conditions until the first quarter of this year; a prolonged labour shortage at oil palm estates in Malaysia; oilseeds farmers refraining from selling; and biofuel policies.

GAPKI expects palm oil to stay above US$1,000 per tonne in the first half of 2022 and potentially for the rest of the year. It projects weaker output growth from Indonesian estates due to lack of new replanting, adverse weather and low fertiliser use. Indonesia’s palm oil stock for 2021/22 is forecast at 3.8 million tonnes, much lower than 4.9 million tonnes in 2020.

Palm oil trading trend in 2022 will depend heavily on the biodiesel mandate, which has been fueling price support. The success of the Indonesian Export Tax system provides significant insulation from further palm oil price volatility. This has also been aided by the level of vegetable oil stocks and the market’s tightness since the Covid-19 pandemic.

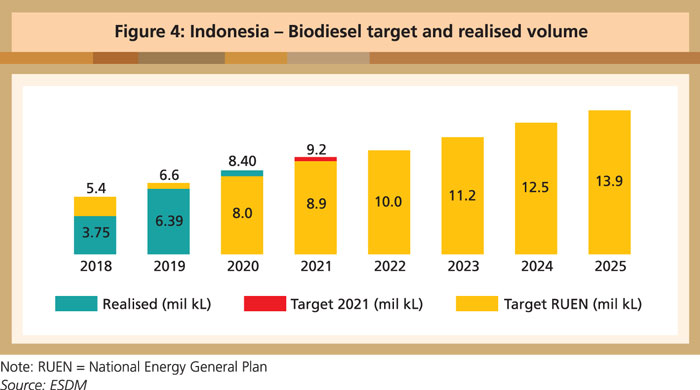

Indonesia’s B30 biodiesel mandate is likely to stay for 2022 and 2023 before the green diesel or hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) is commercially available. The government has raised the B30 biodiesel quota for 2022 to 10 million kilolitres. In 2021, Indonesia expanded its biodiesel allocation by 213,033 kilolitres to 9.4 million kilolitres. This will continue to support palm oil prices with the higher domestic demand.

Based on data from the Indonesian Palm Oil Fund Management (BPDPKS), the 2021 export levy collection is estimated at between US$4.87 billion and US$4.94 billion, of which US$3.4 billion or 70% is being used to support the B30 biodiesel programme. In 2022, BPDPKS estimates that the biodiesel mandate funding will be US$2.7 billion. Funding from the palm oil exports levy is still sufficient to support the mandate into 2022.

In 2022, Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources plans road tests on the B40 blend, in two options. The first is a 30% biodiesel and 10% HVO blend, and the second is a 30% biodiesel and 10% distillate fatty acid methyl esters combination. The government is executing a comprehensive study on the B40 blends and aims to partially implement this mandate in 2025. The biodiesel mandate and palm oil export levy collection are supportive of biodiesel production from 10 million kilolitres in 2022 to 13.9 million kilolitres in 2025.

Current developments look promising in the US. The USDA’s Economic Research Service recently projected higher soybean oil demand in 2022, while Rabobank foresees greater crush capacity beginning in 2023 as more renewable diesel facilities come online. Renewable diesel in the US has multiple government policies driving new production. The Renewable Fuel Standard generates renewable identification numbers for renewable diesel subsidy. There is also the US$1-per-gallon Biodiesel and Renewable Diesel Tax Credit that is set through 2022 but could be extended through 2026 in the Build Back Better Act.

Rabobank projects renewable diesel production to hit more than 6.1 billion gallons by 2030. That would push vegetable oil demand to about 21.4 million tonnes. To put that into perspective, Rabobank notes that the US is producing about 11-11.3 million tonnes. Basically, that requires double the volume of soybean and other vegetable oils to meet the demands of renewable diesel. Many analysts forecast continued high demand for soybean, inevitably boosting palm oil prices.

CPOPC is of the view that palm oil output will remain constrained with limited upside potentials, and that prices will likely continue to trade in the bullish range of US$1,000 per tonne. However, the palm oil price rally forecast in 2022 could be dampened by higher soybean oil output in Brazil.

In 2021/22, Brazil and Argentina’s soybean production is estimated at 147.9 and 45.8 million tonnes respectively. Record high soybean production is expected in the 2021/22 season unless adverse weather conditions amid La Nina significantly deteriorate growing conditions. The upside potential of soybean yields could also be limited by concerns over lower or delayed input applications, following soaring fertiliser and pesticide prices.

While these factors support bullish vegetable oils prices in 2022, there are worries over the recurrence of Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns due to the emergence of the Omicron variant, thereby slowing global economic recovery.

CPOPC

Jakarta, Indonesia

This is an edited version of the article which is available at

https://www.cpopc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CPOPC-OUTLOOK-2022.pdf