Falie is a typical rural Liberian settlement with a population of around 1,500, roughly 24km off the nearest covered road. The houses are rough and ready, using local timber, mud and corrugated iron. No running water, no sewerage, no electricity, no health clinic, no school, no shop. Not much, in effect, apart from a tightly-knit community spirit and intense loyalty to the Zodua Clan, made up of Falie itself and two similar settlements, Gohn and Karnga – 4,760 people in all, and what seems like a long way from the capital, Monrovia.

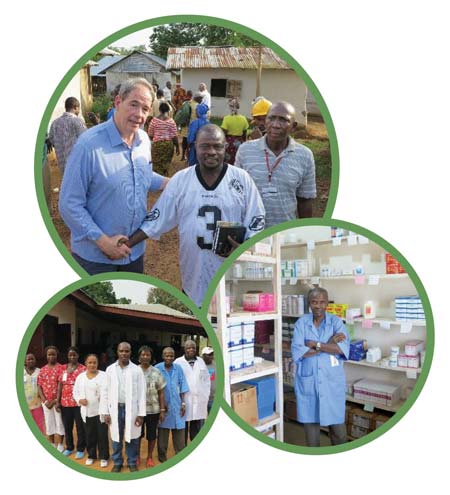

I’m there to meet about 20 community leaders, together with Simon Lord, Chief Sustainability Officer for Sime Darby Plantation Sdn Bhd, Malaysia’s largest palm oil company, and representatives of Sime Darby Plantation Liberia (SDPL).

The Zodua Clan has ‘customary rights’ over around 15,000 ha of surrounding forest, 4,000 of which have been designated as ‘suitable for oil palm development’ as part of the deal struck with the government of Liberia in 2009, allocating Sime Darby a concession area of 220,000 ha. But a deal done in Monrovia is one thing; making it stick at the local level is altogether different.

It took five years to negotiate the necessary Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) agreement with two of the three settlements – Karnga’s has yet to be done. It included compensatory payments to the communities for loss of farming land, preceded by detailed ‘participatory mapping’, which made it possible for SDPL to plant the first 250 ha, with high hopes of completing the whole 4,000 ha in short order.

Then came Ebola, a horror story for that region, which put everything on hold for 18 months. Then came the moratorium. And that’s where it gets personal for me.

In January 2014, Sime Darby was one of six signatories to the Sustainable Palm Oil Manifesto, in which they all committed to no further deforestation, no planting on peat, and no exploitation of workers and communities. I was present in Kuala Lumpur when the Manifesto was signed, and very actively involved subsequently in helping to determine exactly what is meant by ‘deforestation’, as the Co-Chair for 18 months of the High Carbon Stock (HCS) Science Study.

In September 2014, a moratorium was imposed on all new planting that would otherwise have proceeded at that point – including in Liberia. This was done as a stop-gap, temporary measure, but the debate about what is or isn’t ‘HCS’ forest has been going on since then.

That well-intentioned moratorium suddenly begins to look very different here in Falie, surrounded by people whose lives have been very negatively impacted, not by deforestation, but by all new development being put on hold. And it’s still on hold.

Listening to members of the Zodua Land Committee, speaking at the meeting in Falie

The mood is friendly, but tense. There’s a lot of frustration, articulated by Bai Sembeh, the Chairman of the Zodua Land Committee, in his opening speech: ‘We didn’t want Sime Darby to leave our land before, and we don’t want you to leave it now. It’s our land, to do with as we want. You didn’t have to bribe us: we did a deal. And we still don’t understand why you’ve broken your promise to continue planting.’

The concerns start coming thick and fast. Before the deal with Sime Darby, people had to drink from the river, which was often contaminated, but Falie now has a number of shiny new hand pumps, provided by the company. A nearby clinic and pharmacy serve the community’s healthcare needs. Expectations are high.

Since the end of the horrendous civil war in 2003, they’ve got used to the fact that neither the government in Monrovia nor the battalions of foreign aid workers in the country were ever going to be able to do anything much to help them. Armchair environmentalists in the US and Europe might not like it, but SDPL is all that stands between them and near-permanent destitution.

‘If you go now, what do you think is the way forward for us? Who’s going to sort out that road? Who’s going to stop our children getting sick? Is anyone else going to provide any jobs?’… Simon and SDPL General Manager Rosli Taib patiently seek to answer each and every point.