Hungary, with a population of 10 million, is a landlocked country in central Europe. Nearly one-fifth of the population lives in Budapest, the capital city.

A few years after Hungary joined the European Union (EU) in 2004, declining exports, reduced consumption and fixed asset accumulation hit its economy hard. During the 2008 financial crisis, the country entered a severe recession, with its economy shrinking by 6.4% – one of the worst contractions in its history.

A downward spiral set in. Banks gave out fewer loans and investment activity plummeted. This, along with growing price sensitivity of the consumer, caused a decline in consumption, resulting in job losses and further reduction of economic activity. Inflation did not rise significantly, but real wages dropped.

After the 2010 election, the economy began to recover with a big boost from exports, especially to Germany. In 2011, a growth rate of about 1.7% was achieved. At the end of the year, the government turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the EU for financial support, to refinance its foreign currency debt and future bond obligations. When Hungary rejected the economic policy recommendations favoured by the EU and IMF, talks broke down in late 2012.

In 2016, the Hungarian economy grew by 2%. The government is pursuing two goals in its economic policy: the creation of one million new jobs over the next 10 years; and the transformation of the legal framework to make Hungary ‘the most competitive economy in Europe’.

Pushing on

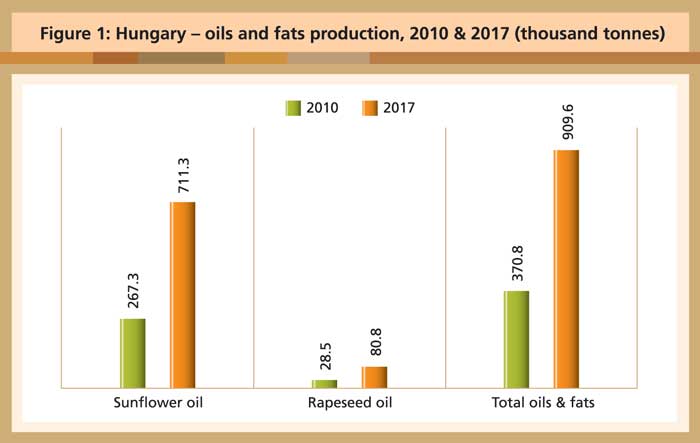

Of Hungary’s production of oils and fats in 2016, 75% comprised sunflower oil. It is interesting to note that domestic production, in general, has been growing significantly in recent years (Figure 1).

Source: Oil World

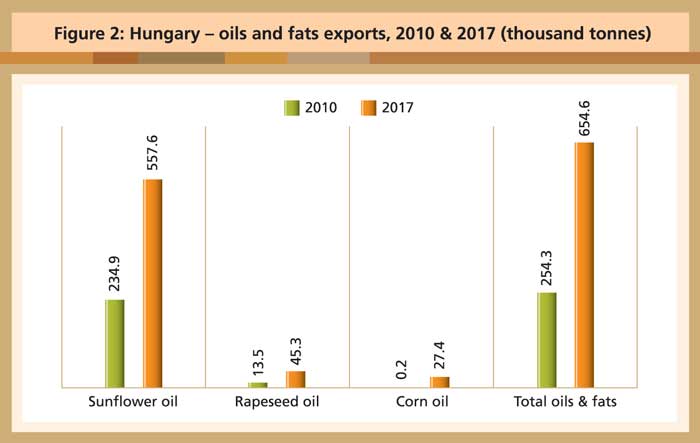

In line with the political goals to push the economy forward, exports have seen impressive growth since 2010. Oils and fats exports more than doubled during this period (Figure 2), carried mainly by sunflower oil.

Source: Oil World

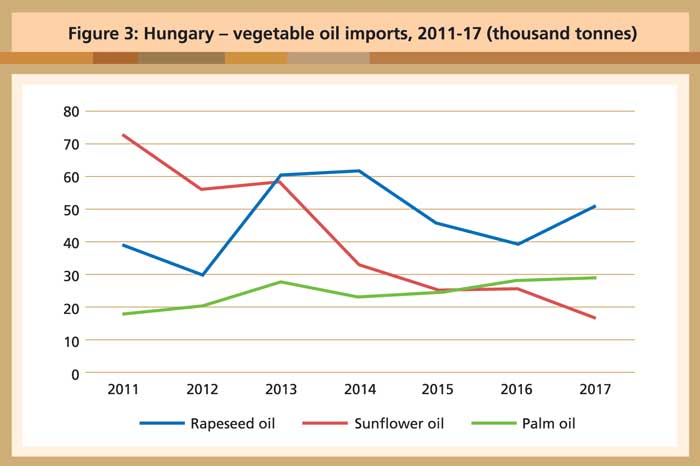

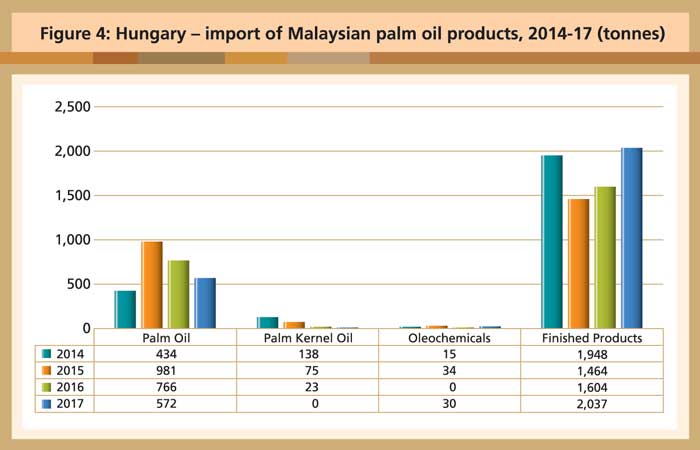

Imports are moving at a much lower level. Intake of rapeseed oil and sunflower oil has fallen in the long-term trend (Figure 3). Only palm oil imports have grown over the last couple of years, with finished products topping the list (Figure 4).

Source: Oil World

Source: MPOB

Hungary’s economic policy appears to be aimed at supporting export industries and substituting imports where possible. At the same time, there is an effort to attract foreign direct investment to grow the employment base.

This approach is manifested in the oils and fats sector as well – domestic production and exports have expanded, while imports have remained relatively lacklustre. With Hungary trying to shape itself into an export base for the EU and eastern European neighbours, there may be a role for palm oil in supplying inputs to processing industries.

MPOC Brussels