... when it makes or reviews laws and policies

December, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Comment

The European Union (EU), under its commitment to transparency, has improved avenues for stakeholders – both citizens and foreigners – to participate in its legislative and policy-making processes.

Interested parties may access information on trade negotiations and policy initiatives, as well as offer their views at various stages. The main opportunities for feedback arise during the Roadmap and Inception Impact Assessment stage, and when the proposal is drafted.

Such consultations allow stakeholders to help shape EU policies and legal instruments. They can educate legislators and regulators on specific issues, while gaining a constructive understanding of EU initiatives.

The European Commission (EC) is responsible for proposing EU legislation and policies, with the process being guided by its annual Work Programme. In 2016, the EC, the European Parliament and the Council of the EU (Council) signed an Agreement on Better Law-making.

Since then, the EU has developed its ‘Better Regulation’ agenda, involving a shared commitment by its institutions to ensure ‘evidence-based and transparent law-making based on the views of those that may be affected’.

The EC is also tasked with reviewing and evaluating laws, and to propose improvements where necessary. The Regulatory Fitness and Performance Programme, which is part of the EC’s Better Regulation agenda, aims at evaluating the performance of legislation and ensuring that it maximises benefits for citizens and businesses, while minimising encumbrances.

Before proposing legislation, the EC is required to define the scope of the new measure and assess its anticipated impact. The findings are then published in an Inception Impact Assessment report. According to the EC, the ‘assessments are carried out on initiatives expected to have significant economic, social or environmental impacts’.

A Roadmap is used to define the scope of:

The document includes descriptions of issues to be addressed, the reasons for action and an overview of available policy options. When initiatives are expected to have significant economic, social or environmental consequences, an Inception Impact Assessment is carried out.

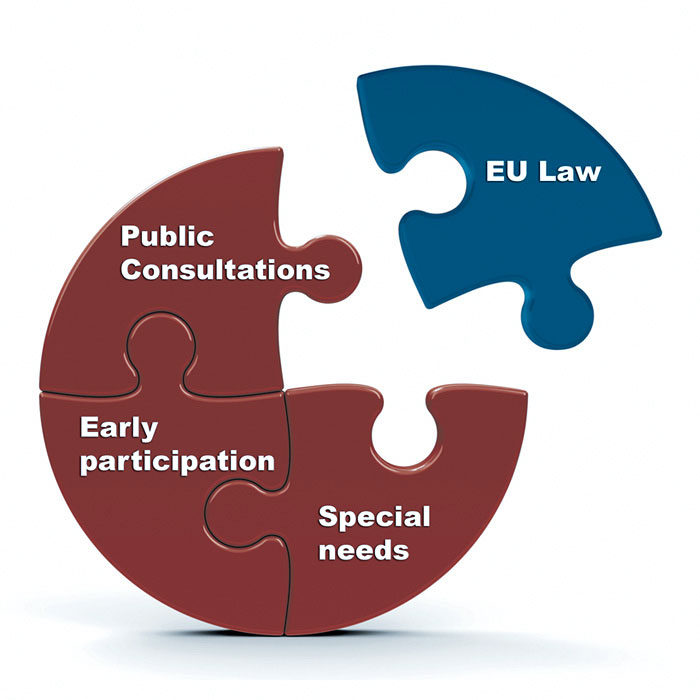

There are three main stages in the process where stakeholders and third countries can provide input:

Effects of consultation

Many EU laws and policies have an impact on trade that is felt far beyond its borders. Therefore, public consultations facilitate insight into the legal, technical and practical issues that could arise during implementation. Potential barriers can be avoided or reasonable alternatives can be considered.

Such input can make a difference in assisting the EC to revise its approach or to review elements of the final measure. This was seen when the EC modified its proposal for a Regulation on the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, as an outcome of consultations during the Inception Impact Assessment stage. Both the EC and various Members of the European Parliament were made aware of certain elements, which then led to a restriction of the scope of the draft Regulation.

While public consultations do not necessarily lead to substantive changes, early participation does allow for issues to be deliberated. Where the EC does not take relevant contributions into account, the engagement can serve as crucial evidence in dispute settlement procedures.

Additionally, public consultations provide an opportunity for developing countries to remind the EU of their special needs. These need to be factored into technical regulations and standards, as well as conformity assessment procedures, under the World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules.

The WTO Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade stipulates that member-countries should consider the ‘special development, financial and trade needs’ of developing countries when introducing technical regulations. Under Article 12.3, member-countries should not create ‘unnecessary obstacles to exports from developing countries’.

Under Article 10.1 of the WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, member-countries must take account of ‘the special needs’ of developing countries when preparing and applying relevant measures.

Malaysia’s palm oil industry should therefore step up to the plate to engage with the EU whenever relevant laws, regulations and policies are proposed. Public consultations provide an effective channel for direct communication and to ensure that issues receive prompt attention.

This may not lead to a silver bullet to redress all the negative effects of EU trade measures. However, the failure to embrace the opportunity would certainly limit Malaysia’s ability to stand up for its economic rights, especially on the beleaguered palm oil front.

Uthaya Kumar

MPOC Brussels