Life as a Plantation Manager

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Plantation, Issue 1 - 2019 No Comments

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Plantation, Issue 1 - 2019 No Comments

A university graduate today has many choices in selecting a career. One of the best would be to work in the plantations industry, which offers a variety of jobs. A long time ago, estates in Malaysia mainly grew rubber, but have since replaced this with oil palm. Most of the plantations are now operated by government investment agencies or family holdings.

To date, oil palm has been planted on about 5.8 million ha in Malaysia, and produces about 20 million tonnes of crude palm oil (CPO) and about 5 million tonnes of palm kernel a year. CPO fetches an average price of RM2,400-2,500 per tonne, while palm kernel has an average price of RM1,800 per tonne. This generates total revenue of about RM60 billion per year. In a good year, the revenue and profit will be higher, as the price can exceed RM3,000 per tonne for CPO and more than RM2,000 per tonne for palm kernel. The kernel is crushed to get oil and cake.

In Malaysia, the yield of the oil palm tree is high, helped by high rainfall of over 2,000mm per year and fertile soils. When mature at about three years old, the oil palm gives an average of one fresh fruit bunch a month, valued at about RM8 per bunch. An efficient management team will try to get the trees to double the number of bunches; this adds to income, while sharply reducing the costs of production per tonne.

At the mill, the palm fruit is cooked and pressed for oil. Again, an efficient management team and workforce will try to increase the extraction rate. The CPO and palm kernel oil are then processed in a refinery and sold to manufacturers of edible and non-edible products.

Buyers use palm oil products in the manufacture of foods, oleochemicals, medicine and cosmetics. Scientists are constantly finding new uses for palm oil in biscuits, chocolate, margarine, medicine, food supplements and detergents, as well as in biofuels.

Manager’s duties

Let’s take a look at the manager’s duties on an oil palm estate of, say, 3,000 ha. Typically, his day starts before dawn, when a driver takes him to the muster ground. The manager stands behind the three assistants and six supervisors, while the 20 mandors read out the workers’ names to take attendance.

The manager looks at the workers in several lines to see if they have turned out with the right shoes and equipment. After receiving quick instructions, they spread out to their areas of work. In the silence of the muster ground, now empty, the manager has a chat with the remaining assistants and supervisors, so all know what they have to do. He always tries to strengthen his team.

As the sun begins to rise, he goes to see the new plantings where the dew is still on the low fronds of young oil palm trees. The rows stretch to the far end and he takes a walk, checking on the circle-weeding done some days ago. Then he is off to see the harvesting. The manager must ensure that harvesting gangs achieve the estimated daily production; he checks for absenteeism, but it is usually low.

He watches a harvester with a sickle at the end of a long aluminum pole, raising it to reach a ripe fruit bunch over six meters above the ground. The harvester slips the blade to the bunch stalk; he steps back, yanks twice and the bunch detaches from the trunk, crashing to the ground. It weighs about 20kg and is worth about RM10. That harvester will cut about 120 bunches a day. That is skilled work.

The manager also inspects other activities around the estate. It could be the manual application of fertiliser. There is a technique to this – the container is swung from waist level towards the back, so that the fertiliser granules spread out in an arc. However, more areas are now being converted to mechanised application using tractors and spreaders. They work faster and help to reduce the need for labour.

Feeder roots take up the nutrients to speed up the growth of the trunk, leaves, flowers and fruit bunches. Fertilisers help increase bunch production and weight. With correct nutrient applications, the trees bear more female flowers. These turn into bunches that are ready for harvest in five to six months.

Such matters are on the manager’s mind as he goes home for breakfast. Yet it would only be 9am, with most of the day still ahead of him. He may again go to the harvesting area or meet the supervisors to hear what they have to say about raising the crop production.

Driving back to the field, he thinks of how the production costs can be reduced if he obtains a higher tonnage of fruit. The figures work in his head, even as his eyes miss nothing. If, for instance, a bridge shows signs of erosion, he gets out of the vehicle and peers under the bridge to assess what it would take to repair it. There is nothing like attending to details.

Once a week, he calls a meeting with the assistants and the chief clerk to review the work done and to check on crop production for the rest of the month. Other matters discussed could be the progress of capital expenditure on new workers’ quarters and the purchase of a road grader and a roller. They have to arrive in time to repair the roads before heavy rains set in. They discuss the date of the next payroll, but this must be kept confidential to ensure security of the cash delivery.

In the evening, the manager may attend a football match between divisions of his estate or against other estates. He may do the kick-off and then watch the game, looking for players who show fighting spirit or leadership qualities. He makes a mental note of their names. They will be on his shortlist for promotion.

By the time he heads home, it is nearly dusk. After a bath and dinner, he reads the newspapers or The Planter magazine published by the Incorporated Society of Planters. He may find scientific, technical and general articles of interest, as well as keep up with the movements of fellow-planters. Today, the news gets to him in many more ways. The fax and the telex have been replaced by the computer, handphone, email and WhatsApp messages.

He must work as a part of a team. For example, he works closely with research scientists as they choose areas for trial plots of new palm progenies and clones. They also look for ways to improve the yield and oil quality, in order to obtain a premium price.

In addition, the manager must know the requirements of sustainable practices as set by the rules of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil and the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil standard. Implementing these might be part of his Key Performance Indicators.

He has many more things to remember and must have updates ready for regular meetings at the head office, which provides support services in accountancy, marketing and sales, human resource management and research.

Before going to bed, he watches the late-night business news on TV. Palm oil prices are moving again. He checks his handphone one last time. There is a request from Marketing for his crop forecast, as well as a question about how much oil and kernel to sell. He notes the urgency, and will reply first thing in the morning. The manager’s views are important for the business.

Mahbob Abdullah,

Director, IPC Services Sdn Bhd

This is an edited version of a paper written for university students.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Plantation, Issue 4 - 2018 No Comments

From the 1960s, Malaysia’s oil palm plantations commenced planting with higher-yielding Tenera palms which yielded up to 30% more palm oil per planted ha. At the same time, a new domestic industry sprang up – production of palm oil mill machinery.

By 1974, a further advance had emerged by licensing in-house palm oil refining, fractionating and bleaching. In the 1980s, technology had been developed to transform palm oil mill liquid waste from a costly effluent to a profitable feedstock to generate electrical energy. Production research took a further leap forward by the multiplication of selected palms through clonal technology in the 1990s.

Source:

* https://data.world bank.org/indicator/AG.LND.AGRI.ZS,2015

** https://world bank.org/indicator/AG/LND.FRST.ZS,2015

Forest cover

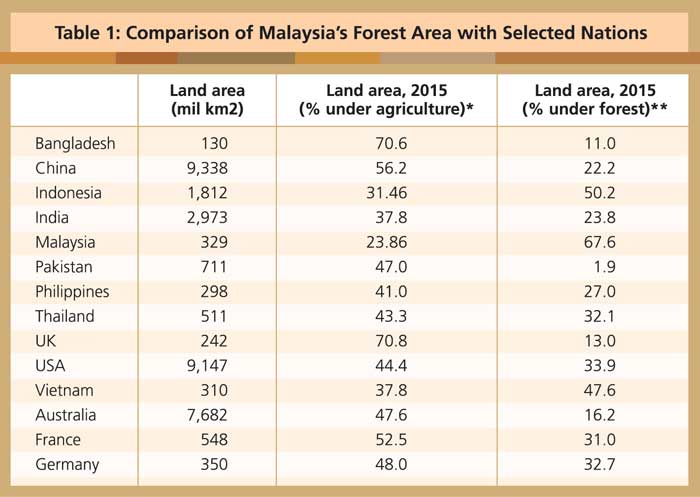

Indonesia, as at 2017, has maintained 50.2% of its land area under forest cover. Malaysia appears to have maintained 67.6% natural forest cover (World Bank data, 2015). Currently, 17.6% of Malaysia’s landmass, or 5.7 million ha, remains undeveloped – less than the existing oil palm planted area of 5.8 million ha (MPOB, Dec 31, 2017).

A Malaysian national policy to preserve 50% (16.4 million ha) of natural forest cover would allow licensing of 11.4 million ha (35% of the landmass) for oil palm plantations, while preserving status quo with Indonesia in relation to Malaysia’s 1992 Earth Summit pledge of 50% forest cover. Malaysia’s all-important plantation economy has consistently emphasised its commitment to reducing carbon emissions and maintaining biodiversity.

The developed world (with some notable exceptions) records about a third of its land area devoted to forestry; the developing world in Southeast Asia records up to half of its land area devoted to forestry. The exception is Malaysia where, in 2015, 67.6% of its land area was shown to be under forest. Have Malaysian land-use policies been targeted by foreign NGOs financed or subsidised by nations which prop up domestic production of oilseeds?

CPO consumption

Halting the 1981-2018 ‘oil palm fever’ has refocused national priorities from plantation investment to maximising the fresh fruit bunch (FFB) and crude palm oil (CPO) production per planted ha, with strong emphasis on product quality and marketing. It marks the end of a 37-year bull run which has seen palm oil increase from 7.8% of worldwide supplies of edible oils in 1980 to 35% in 2017.

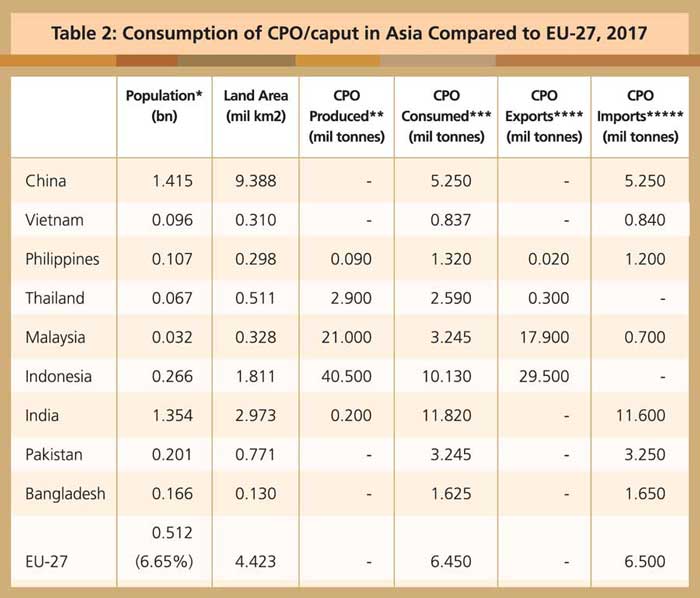

CPO consumption/caput/annum was 101kg/caput in Malaysia, 38kg/caput in Indonesia and 13kg/caput in EU-27 in 2017 (Table 2). These figures contrast sharply with the average annual consumption (7.2kg/CPO/caput for the rest of Southeast Asia).

Source:

* www.worldometeters.info/world-population/population-by-country, 2017

** www.indexmundi.com/agriculture/?commodity=palmoil&graph=production, 2017

*** www.indexmundi.com/agriculture/?commodity=palmoil&graph=consumption, 2017

**** www.indexmundi.com/agriculture/?commodity=palmoil&graph=exports, 2017

***** www.indexmundi.com/agriculture/?commodity=palmoil&graph=imports, 2017

By gofb-adm on Thursday, August 2nd, 2018 in Issue 2 -2018, Plantation No Comments

The Pareto Law, also known as the 80/20 principle, is useful in the planning of marketing strategies. Essentially, it states that 80% of the results will be derived from 20% of the input. For example, 80% of company profits will be generated by 20% of the products, or 80% of sales will come from 20% of the premium customers.

The Pareto Law was developed by Vilfredo Pareto of the University of Lausanne in 1896. In his first paper, he stated that 80% of the land in Italy belongs to 20% of the population. He then carried out a survey in other countries and observed a similar distribution.

Business managers are increasingly making use of the Pareto Law to analyse the impact of their marketing budget, sales distribution, customer complaints, feedback and service plans.

The Pareto Law also has a place in daily plantation operations, with everyone from the general manager to the agronomist being able to apply it to their area of work. These are some rules of thumb:

Reasons to apply the principle

Senior planters may be dubious about such measures. They may have many questions – particularly about the recommendation to target 20% of any area of plantation management in order to improve overall results. To view the situation holistically, we have to understand the evolution of plantation management.

During the mechanical era, new machinery and equipment were developed. The chemical revolution resulted in improved fertilisers and crop protection products. The biogenetic revolution saw the promotion of biogenetic annual crop seeds with better yield.

We are now experiencing the fourth agricultural revolution, involving the Internet of Things. Agricultural start-ups are looking at new concepts such as using sensors to capture basic raw data (moisture, rainfall and sunshine duration) to predict the yield, with complex logarithm programming for annual crops. Unmanned robotic tractors to Unmanned Aerial Vehicles are used to carry out spraying, manuring, census and mapping using hyper-spectral cameras.

In order to act quickly and correctly within a limited time-frame – while coping with acute labour constraints – we have to rely on emerging technology tools like intelligent software, logarithm studies, distribution patterns or big data management.

The 80/20 principle is a simple mathematical distribution model that is capable of capturing data for many years to come. Applying the Pareto Law in daily operations will also enable productive use of time toward efficient and effective management of plantations.

Devarajen Rajagopal

Developer, Oil Palm Pesticides Calculator