Issues involving Covid-19 and Brexit have dominated attention in the UK over the past year. The country has been one of the worst affected in Europe by the pandemic, even as it grappled with the legal complexities of leaving the European Union (EU). But what are the implications of both issues for the UK’s palm oil trade?

Take Covid-19. The initial wave ran roughly from January to June 2020, and was more severe than on much of the European continent. In December 2020, a mutation of the coronavirus named B.1.1.7 was discovered in the UK. It proved to be much more contagious than the original virus. Consequently, the government had to announce a third lockdown on Jan 4 this year.

And Brexit? For years, this debate was at the heart of the daily news in the UK. Now the separation is complete. The UK officially left on Jan 31 last year, but the transition period only expired at the end of 2020.

Politicians, businesses and the population were supposed to prepare for the exit. This went down to the wire. Shortly before the deadline and with a no-deal scenario looming, EU representatives and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson finally agreed on rules to organise future relations.

After 4½ years of uncertainty and speculation, a Trade and Cooperation Agreement negotiated between the EU and the UK entered into force provisionally on Jan 1 this year. It puts their economic relationship on a new footing.

The deal establishes, among other things, a comprehensive trade partnership. At its core is an agreement providing for neither tariffs nor quotas for virtually all products exchanged between the UK and the EU.

However, there is a caveat: A prerequisite for duty-free treatment is compliance with the rules of origin. Duty-free treatment applies only to products originating from the contracting parties. In other words, it is only granted if goods originate in the EU or the UK.

There are several qualifications as to what ‘originating in the EU’ means. Among them is a stipulation that considers goods originating outside the UK as eligible for free trade treatment if they have been sufficiently worked or processed. Only a certain proportion of input materials from third countries may be used. Product-specific rules of origin are to be observed.

UK palm oil trade

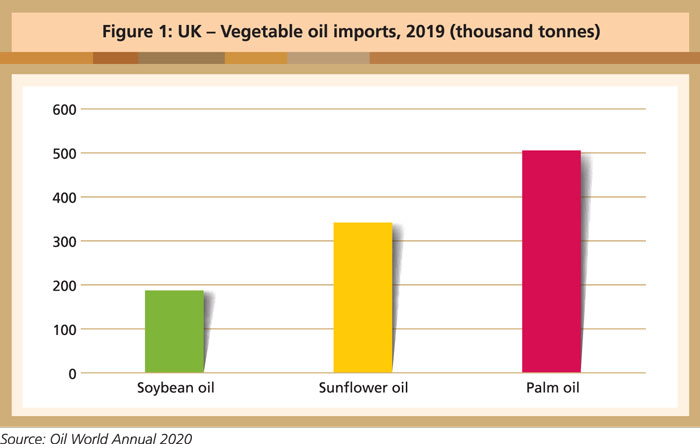

Based on the latest available Oil World figures, the UK in 2019 imported 505,900 tonnes of palm oil, making it by far the leading vegetable oil import (Figure 1).

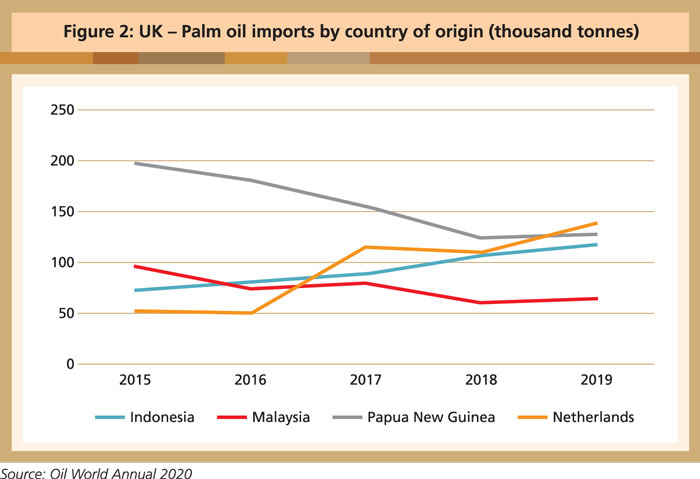

The import volume includes shipments via intra-EU trade. The leading country of origin for palm oil imports in 2019 was the Netherlands, followed by Papua New Guinea (Figure 2). The volume that the UK sourced directly from producing countries stood at 320,000 tonnes.

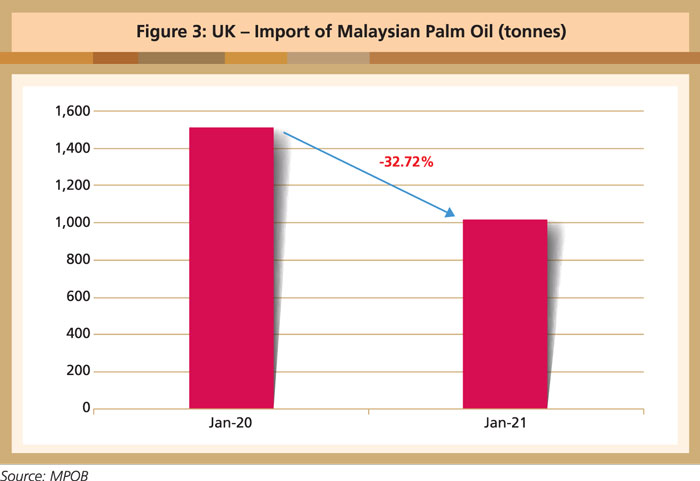

The Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) recorded an export volume of 15,505 tonnes of palm oil to the UK from January to December last year. There was a decrease of more than 32% in the comparative volume for January 2020 and January 2021 (Figure 3).

One reasonable interpretation of the MPOB data is that they show the double effect of Brexit and Covid-19 on the UK’s economy. Its GDP last year had shrunk by a full 9.9%, which was worse than in most European countries. Many observers point out that this was the poorest economic performance since 1709 when the ‘great frost’ led to a failed harvest.

Variable prospects

The UK economy will remain in dire straits this year for the same reasons – Covid-19 and Brexit. An overall slump in demand for palm oil in projected, as the Covid-19 lockdown takes its toll on the hotel, restaurant, tourism and transport sectors in particular. Brexit issues have also severely hampered trade with the EU, which has been the UK’s most important partner.

The British Road Haulage Association sounded the alarm in a letter dated Feb 1, 2021, to Michael Grove, the Minister for the Cabinet Office. It reported a 68% drop in UK exports to the EU, compared to the previous period. At the same time, many EU goods cannot find their way across the Channel, leading to an increase in consumer prices, as well as further lowering demand.

Amidst this, however, there is a possible upbeat scenario for palm oil. First, the post-Brexit trade agreement contains provisions on rules of origin that conceivably might work in favour of palm oil. They aim at zero tariffs or quotas on goods traded between the UK and the EU – provided the rules of origin are satisfied.

The rules entered the agreement because the EU obviously wants to avoid circumvention should the UK import duty-free items from third countries, and then re-export – also duty-free – to the EU.

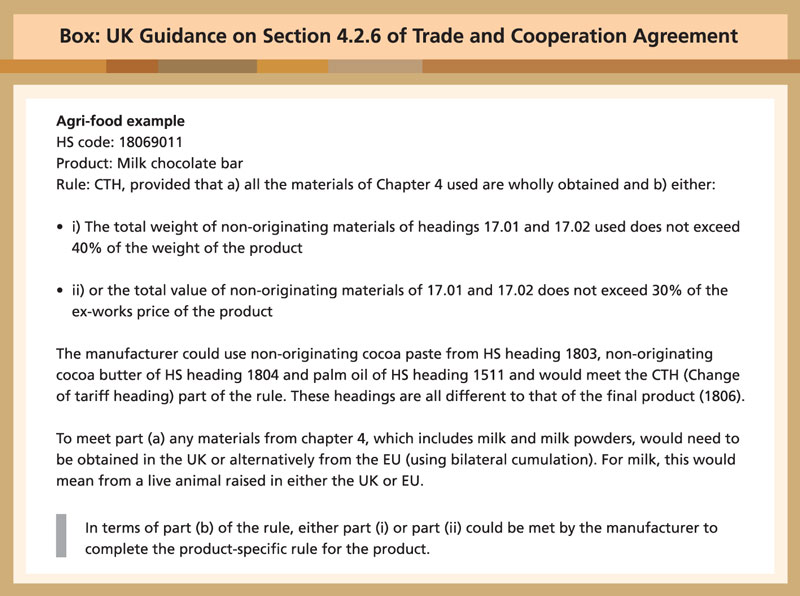

However, there may be certain exemptions for palm oil, based on guidance published by the UK government in relation to Section 4.2.6 (see Box). It appears to imply that products like chocolate bars containing palm oil can continue to be exported duty-free to the EU.

A second segment that might be favourable for palm oil concerns biofuels. Now that the UK is no longer in the EU, the rules of the RED II on phasing out palm oil in biofuels by 2030 no longer apply. The emerging scenario is still foggy, and issues of how the UK and the EU will design that part of its relationship have been delegated to expert groups.

Still, the chances are that the UK is keen on getting on the right side of palm oil-producing nations in Asia, as it wants to strike trade deals in line with its ‘Global Britain’ initiative. As Bloomberg had opined in 2019: ‘Post-Brexit, the UK will have a historic opportunity to strike a trade deal with one of the world’s fastest-growing regions and prove that it can shed European red tape and protectionism. The key is to rethink the European Union’s policy on palm oil.’

This assessment points to a trend that could work in favour of palm oil in the long term. ‘Global Britain’ is the UK government’s mantra for redefining the country’s role in a post-Brexit world. Large portions of the concept still have to be filled with substance, but a charm offensive regarding Asia is already underway – and palm oil is a central issue there.

On Feb 1, 2021, Great Britain formally applied to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, of which Malaysia is a founding member. The UK is the first non-founding country to apply for membership. And its government is wary of the fact that palm oil could become a sticking point in the negotiations.

Jon Lambe, UK ambassador to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, has been quoted as saying: “From my perspective, this is an area where it is important we work together. There is a strong consumer demand in the UK for palm oil and palm oil products. There is a strong industry in Malaysia and Indonesia and it is vital that we work together to ensure that both ends of that supply chain are content.”

It is therefore possible that Brexit will usher in a new dawn for palm oil in the UK – and for Europe, through the British back door. Due to Covid-19, though, this could take time.

Uthaya Kumar

MPOC Brussels