2020 is forecast to be a good year for palm oil in terms of a remunerative price for producing countries. Indonesia and Malaysia are the two biggest producers and exporters of palm oil globally. Other major producers are Thailand, Colombia, Nigeria, Guatemala, Honduras, Ecuador, Papua New Guinea, and Ghana.

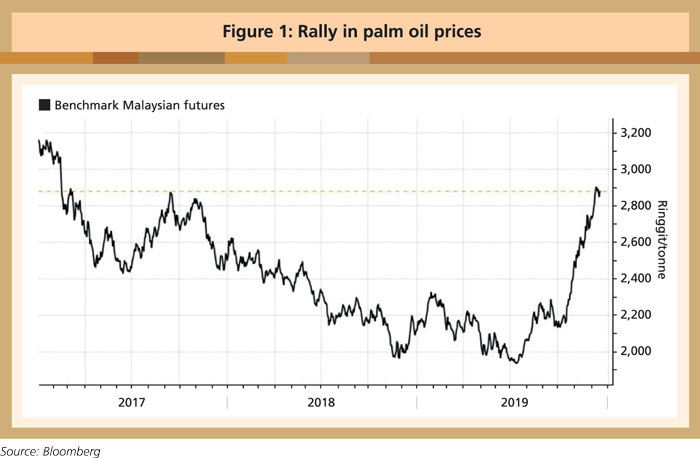

Crude palm oil (CPO) prices have been on a rallying trend since October 2019, peaking above RM2,800 per tonne on Dec 9. Palm oil prices over the first nine months of 2019 were subdued because of persistent high stock, slower demand from major importers India and China, and the European Union’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED) II, which will phase out palm oil deemed unsustainable from its biofuel market by 2030. Differences between Malaysia and India in October were projected to further dampen sales and prices.

The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) organised the first Palm Oil Supply and Demand Outlook Conference (POSDOC) in Malaysia on Oct 22, 2019, to change the perspective of the market. As palm oil is a market-driven industry in many producing countries, CPOPC wanted all stakeholders to be cognizant of, and updated on, the supply, demand and price in the global market going into 2020. The market at the time was being fed with gloomy forecasts and a lack of informed data. The next few months will, therefore, be crucial for the industry to digest all the numbers and data going forward.

The focus of the conference was to develop a Supply and Demand Balancing Strategy to ensure that the market price is remunerative for the industry to remain sustainable. The industry needs to explore areas of mutual interest to work together, and to share common experiences to address problems as well as to optimise opportunities.

The conference was successful in providing a strategic platform for interaction and in-depth deliberation on three key aspects related to the palm oil industry, namely production supply, market demand and price outlook. The event enabled CPOPC to publicise the forecast supply and demand messages to sensitise the market. Palm oil prices have soared since then, and the upward trend is likely to continue as demand will increase due to a combination of factors including increased use of palm oil-based biodiesel and low production of palm oil in 2020.

The discussions at POSDOC were amplified at the International Palm Oil Conference in Bali, Indonesia, at the end of October. This gave another push to prices, extending the rally into November. Enthusiasm in the market was attributed to these factors:

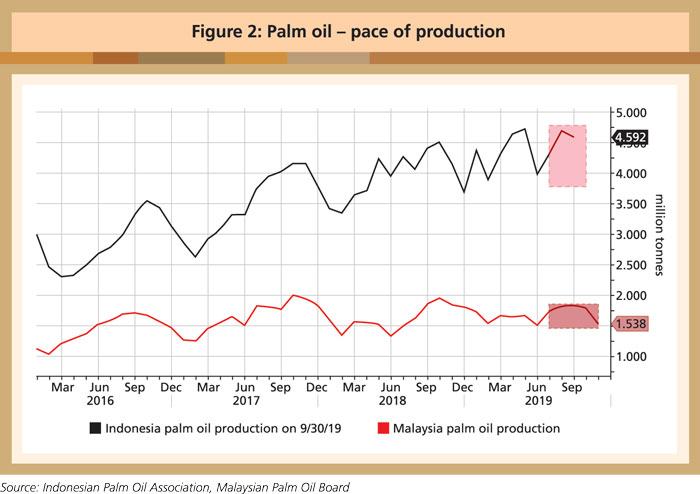

1. The lengthy drought in Sumatera and Kalimantan early in 2019 resulted in many palm oil companies reducing fertiliser application, as the oil palm trees would not benefit much under extremely dry conditions. Additionally, due to persistent low palm oil prices over the year, companies decided to minimise their expenses by reducing manuring. This led to decreasing fruit production and eventually reduced palm oil supply.

2. Several analysts, including at the Globoil Conference held in Mumbai, India, in September, predicted that the palm oil price would be flat until the end of 2019 and in the first quarter of 2020. Discussions during Globoil also suggested that Indian importers would not buy palm oil from Malaysia, possibly to create an oversupply situation in Malaysia to cause a price collapse. As a result, Indian buyers started to buy from Indonesia. However, they unexpectedly lost their bargaining power in the duopoly market. Indonesia could not meet the sudden demand without raising the price. This also lifted the Malaysian price, but it was relatively lower, leading to further positive trends.

3. The bullish sentiment was also attributed to mandatory biodiesel programmes. It is well accepted that the recent price spike was due to Indonesia’s announcement to launch the 30% biodiesel blend (B30) programme in 2020. This will absorb over 9 million tonnes more CPO. Malaysia is preparing for B20 in 2020. When both volumes are combined, it will generate considerable CPO consumption. The anticipated scenario is that demand will outstrip supply, and the price will increase.

Most industry analysts have forecast that CPO prices will remain at elevated levels in 2020. Benchmark futures may average RM2,600 (US$628) a tonne, the highest in three years, according to the median of 25 estimates in a Bloomberg survey (Figure 1), versus an average of RM2,240 reported for 2019. Lower production in palm oil producing countries, increasing biodiesel mandates, and robust food demand will be the key price drivers in 2020.

Production outlook

Analysts are revising their outlook for production in Indonesia and Malaysia due to dry weather and lower fertiliser application. LMC International forecasts global palm oil stockpiles to reduce in 2020, as slow output growth coincides with a boost to biodiesel mandates. The relentless pressure from NGOs to stop oil palm planting, as well as the slowdown in new planting due to low prices earlier and a moratorium in Indonesia, will inevitably keep production growth low for the next few years.

Industry efforts to become more sustainable will become more crucial in 2020, to prevent more companies or countries restricting the use of palm oil. There are fears that the EU, which wants to phase out palm oil use in biofuel, may look to the food sector next.

CPOPC has advised producing countries that the EU’s proposed limits on 3-MCPD esters may impact palm oil use in food products and are set to be enforced legislatively to meet acceptable safety levels. CPOPC has agreed that a single maximum level of 3-MCPD at 2,500 µg/kg for all vegetable oils should be adopted, as the acceptable safety limit for consumption.

The national palm oil sustainable certification scheme in Malaysia will become mandatory for growers from 2020, even as producing countries continue working together to counter discriminatory measures. Weather calamities that affect soybean crops in the US and South America, or sunflower planting in the Black Sea countries, could also tighten supplies and support edible oil prices, including that of palm oil.

Demand outlook

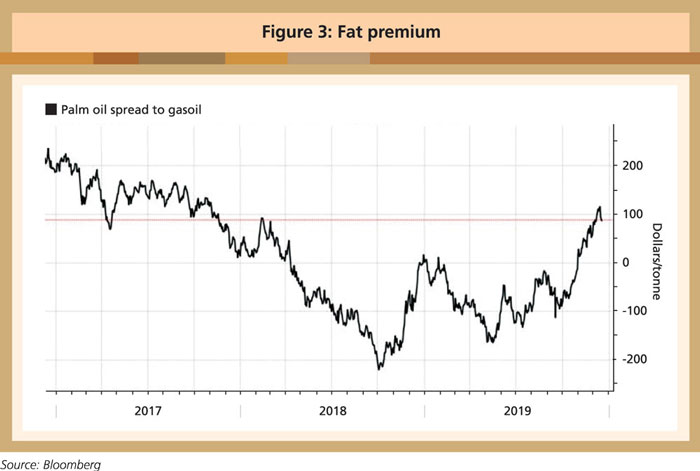

The B30 biodiesel mandate in Indonesia is key to palm oil’s price direction. The policy will help increase CPO prices, improve industry competitiveness, and divert biodiesel to the domestic market. Nevertheless, biodiesel mandates in Indonesia and Malaysia are facing scrutiny, as palm oil trades at a large premium of almost US$100 a tonne to gasoil, compared to an average discount of US$54 over the past year. This will make palm oil more expensive to blend into biodiesel, and will require increased financial incentives. Indonesia has decided to re-impose export levies to fund the mandate starting from January 2020. Malaysia has announced the imposition of export duty from January 2020. Any failure to fulfil the mandate would not support palm oil prices.

The price rally has been so sudden that it threatens the traditional perception that palm oil is a ‘cheap’ vegetable oil for food and fuel. Palm oil hit parity with soybean oil for the first time since 2011, reducing its price competitiveness against other edible oils and prompting buyers to consider alternatives. While a political argument between Malaysia and India disappeared in November, the markets are still on the lookout to see whether India may increase import duties, which could affect palm oil purchases.

China, meanwhile, has increased its buying since July as African Swine Fever reduced its hog rearing industry and lowered domestic demand for soybean meal. The China National Grain and Oils Information Centre expects palm oil imports to reach a record 7 million tonnes in the year starting October to fill the gap.

Palm oil performance – Indonesia

Palm oil is one of Indonesia’s top foreign exchange earners and contributes 1.5-2.5% to Gross Domestic Products (GDP). It directly and indirectly provides a livelihood for more than 16 million people. It is the second-biggest contributor to exports after coal. Palm oil contributed more than 9% to Indonesia’s total export value in 2018, lower than its contribution in 2017 of 11%. The main reason for the decline was the lower CPO price in 2018 compared to 2017. Low CPO prices continued into the first nine months of 2019.

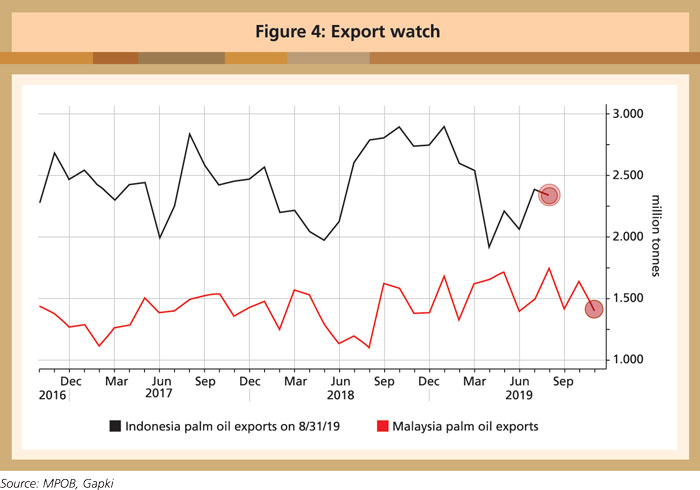

As a consequence, Indonesia’s CPO export value declined 17.2% year-on-year (y-o-y) over the first nine months of 2019, greater than the 10.5% decrease over the same period in 2018. However, Indonesia’s CPO export volume in the January-September period grew 1.9% y-o-y, a reversal of the 1.9% contraction over the same period in 2018. This figure indicates that CPO demand remained strong in 2019, especially from China.

Indonesian palm oil faces serious challenges from its main importers, such as India and the EU. India has been reducing its dependence on the commodity and is shifting to local vegetable oils, such as rapeseed oil. The situation worsened for Indonesian palm oil when India imposed a lower import tariff for Malaysian refined palm oil up to September 2019.

The EU’s stance that Indonesian CPO is not environmentally friendly also threatens demand for the commodity from several countries. However, Trademap data show that the EU’s CPO import volume grew 8.2% y-o-y over the first seven months of 2019, despite the negative campaigns.

In order to promote sustainable palm oil and combat negative campaigns, Indonesia has maintained the moratorium on issuing permits for new oil palm plantations while enforcing sustainability standards through the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil certification programme.

Palm oil performance – Malaysia

Palm oil is still the best agri-commodity in Malaysia. The industry contributed 4.5% to the GDP and RM67.5 billion in export earnings in 2018. However, the export value declined because of the lower CPO price in 2018 compared to 2017. The low price continued into 2019. Based on the Malaysian Palm Oil Board average CPO price, the forecast for 2019 was RM2,120 per tonne, supported by a strong average of RM2,820 per tonne in December 2019.

Internally, CPO supply will likely decrease in 2020 due to lower production. The lower CPO price throughout 2019 has forced growers to reduce fertiliser applications, especially in plantations owned by smallholders whose productivity is lower than those owned by private companies. The lack of fertilisers will reduce production from the fourth quarter of 2019 up to 2021.

There was a report of drier weather and lower rainfall volume for 3-4 months in Pahang, Selangor and Perak in the first quarter of 2019 and Sabah in the third quarter. There will be fewer fresh fruit bunches (FFB) due to floral and bunch failure during the dry season; this will affect production in 2020. In November and December, several states in Peninsular Malaysia were flooded, and this may affect the harvesting and transportation of FFB.

CPO production will also be limited because there will be a small increase in the total plantation area this year. Malaysia has enforced new policies, such as the capping of the total oil palm cultivated area at 6.5 million ha; putting a stop to new planting of oil palm on peatland; banning the conversion of forest reserved areas for oil palm cultivation; and opening up oil palm plantation maps for public access.

The Malaysian palm oil industry is facing significant challenges in complying with the national sustainable certification standard, with over a third of plantations yet to meet the criteria. The Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification, which requires growers to meet certain standards on protecting the environment and workers’ rights, is mandatory from January 2020. As at the end of October, about 58.3% of close to 5.9 million ha of land under oil palm cultivation had achieved MSPO certification. As the country enters 2020, significant challenges remain in achieving 100% mandatory certification.

Looking ahead

Palm oil production in Malaysia and Indonesia is expected to be flat in 2020. Low or no fertiliser application in the first half of 2019, dry weather and lower planting of new areas will combine to give a production increase of just 1 million tonnes. Malaysia’s CPO output was projected to rise by 2.6% to 20 million tonnes in 2019. Lower output of 19.3-19.5 million tonnes is expected in 2020. Indonesian output is forecast to increase by just 1 million tonnes to 44 million tonnes.

From March 2020, world stocks of vegetable oils are likely to deplete, making the price outlook bullish. There will be higher demand from key markets like China and India, and a push to use more palm oil in biofuels by Indonesia and Malaysia, which will augur well for lower stocks and higher prices.

China’s soybean crushing activity and imports of rapeseed and rapeseed oil are expected to fall, leaving palm oil with a big opportunity. China has turned out to be the best importer for palm oil in 2019 and will continue to be so in 2020 due to edible and industrial demand. Palm oil and sunflower oil will replace soybean oil. China is a palm olein market; as long as the palm olein price discount to soybean oil is still good, there is an opportunity to gain a bigger market share. The good news is that, despite large imports of palm oil in 2019, the inventory in China is still low.

India, the world’s top edible oil consumer, is set to import 16.3 million tonnes of edible oils for the 2019/2020 marketing year which started on Nov 1, compared to 15.6 million tonnes previously. Of this, palm oil imports will make up 9.9 million tonnes, slightly up from 9.5 million tonnes previously. Demand from India so far is still strong. Its dependence on imports is rising due to flat domestic production and higher per capita income.

Palm oil is still the main imported oil in India. It accounts for a larger sales volume due to competitive pricing; low vegetable oil prices will therefore encourage more consumption. Statistics have shown that, despite big imports, the edible oil stock is still low. This augurs well for palm oil demand as long as its price discount to soft oil is good.

Demand for palm oil for food production will remain strong as the global population grows. Replacing palm oil as a consumer food ingredient will be a challenge, as the commodity has a wide range of derivatives used in various products.

CPO demand for biodiesel will definitely increase because Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand are increasing their blends of diesel and fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) to make biodiesel.

For instance, Indonesia will increase its mandatory biodiesel policy from B20 to B30 in January 2020. The policy is expected to see an additional 3.3 million tonnes of CPO being absorbed domestically to produce 9.6 million kiloliters of FAME by 2020. Similarly, Malaysia is planning to increase its biodiesel blend from B10 to B20 for the transportation sector and B7 to B10 for the industrial sector in 2020. This is expected to absorb more than 1.3 million tonnes of CPO domestically.

If CPO supply becomes limited due to lower fertiliser applications and extreme weather, biodiesel implementation on a national level will further reduce the available volume from both Indonesia and Malaysia. As a result, the outlook for palm oil in 2020 will be positive.

Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries

Jakarta, Indonesia

This is a slightly edited version of the report.