With national borders closed and flights suspended to contain the spread of Covid-19, the global food supply chain stands threatened. Most governments have adequate stockpiles for now but, in the medium and long term, a food catastrophe lurks, especially for importers.

Already, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has warned that a protracted pandemic could disrupt the entire food web, affecting everyone from farmers and processors to retailers.

In addition, as many as 265 million people around the world are facing food insecurity and possible starvation, aggravated by the pandemic. The hardest hit are the poorest in society, because demand for food is inextricably linked to income. Loss of employment leads to loss of income; in turn, this affects consumption.

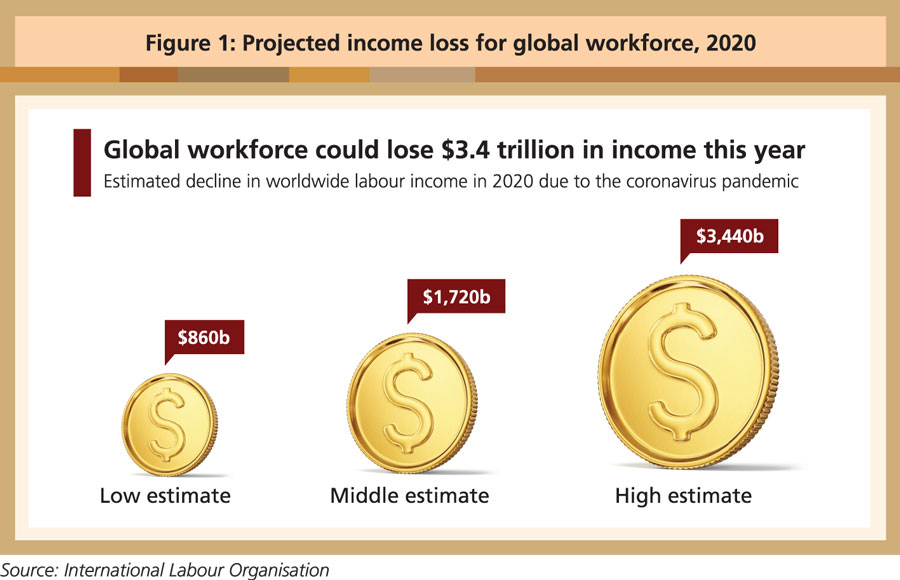

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that the pandemic will push millions of people into unemployment, underemployment and working poverty. According to its estimates, workers could lose between US$860 billion and US$3.4 trillion in labour income this year alone (Figure 1).

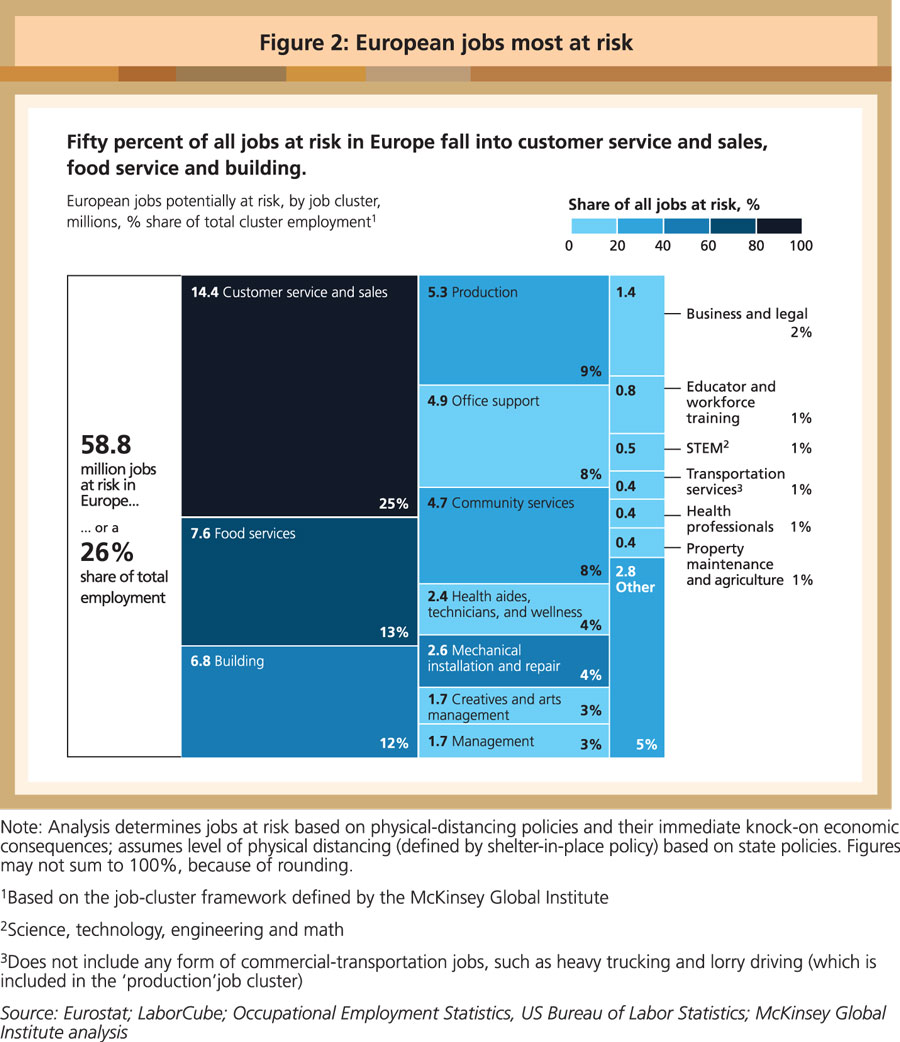

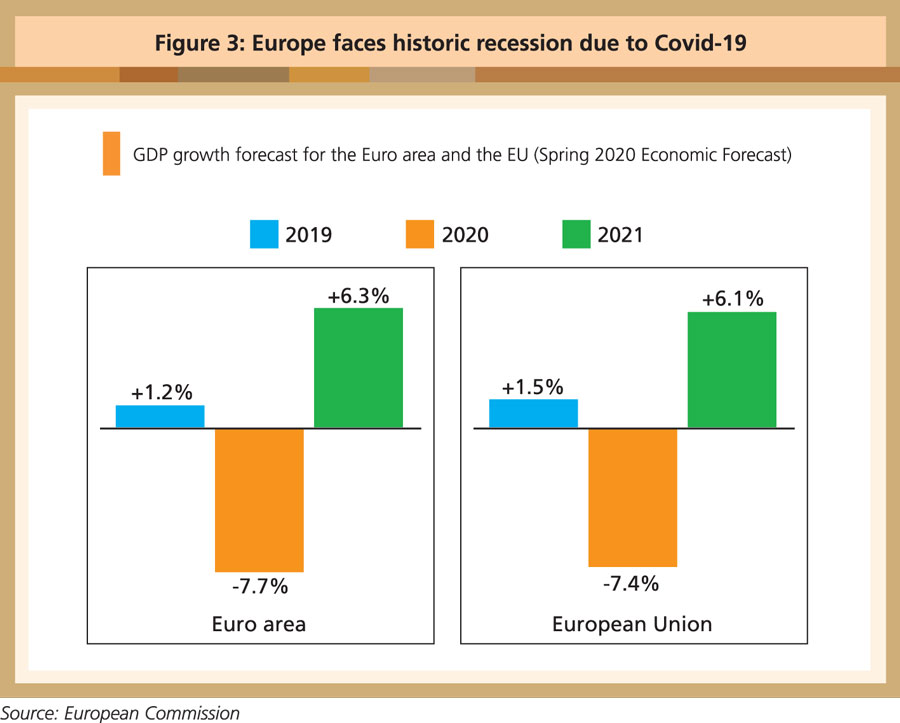

A McKinsey survey estimates that up to 59 million jobs are at risk in Europe (Figure 2) – a staggering 26% of total employment in the 27 member-states of the European Union plus the UK. The European Commission projects GDP contractions of 7.7% and 7.4% respectively or the Euro area and the EU this year, down from previous estimates of 1.2% and 1.4% growth (Figure 3).

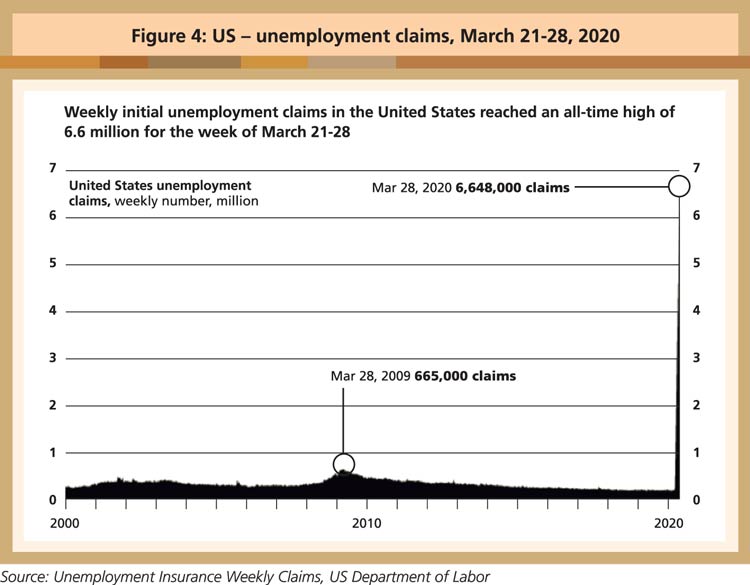

A bleak picture also appears in the US where unemployment claims for the week ending March 28 reached 6.6 million (Figure 4). McKinsey estimates that, prior to the Covid-19 outbreak, about 37 million Americans faced food insecurity. Since the beginning of the outbreak and with the increase in unemployment, an additional 17 million people face food insecurity. That’s a 46% increase.

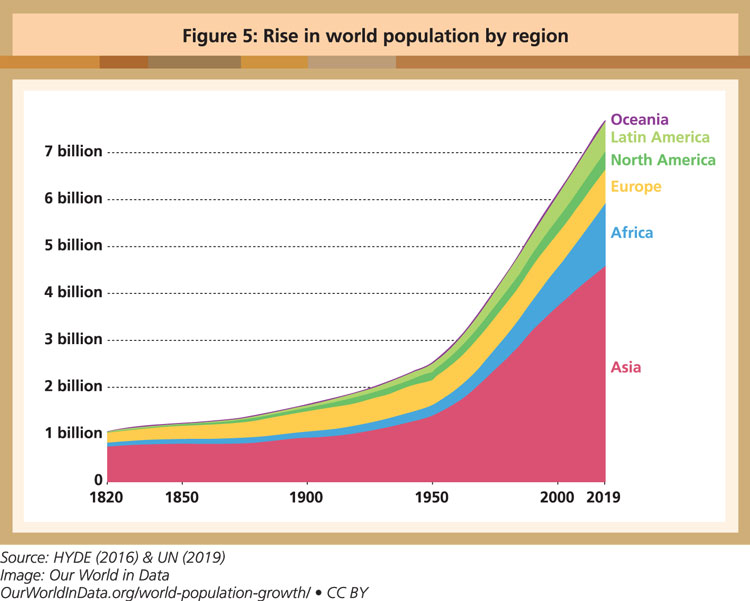

The FAO has sounded the early warning that the agri-food sector will need to generate 50% more food within the next 30 years. A World Resources Institute report outlines that global food production will have to increase by 50% to feed the world’s 10 billion people in 2050.

Agro-based economies therefore have no choice but to keep their food supply chains moving, despite the difficulties posed by the Covid-19 pandemic. However, their activities continue to be scrutinised through the restrictive lens of the environment impact of food production. Food waste and the livestock sector are considered the main emitters of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

‘Local or global’ debate

In ensuring low carbon food for the table, concerns have been raised in particular about transportation and whether locally produced food can lower the rate of emissions. Critics claim that trade in food is bad for the environment due to ‘food miles” – a reference to the carbon footprint caused by transporting agricultural food products over long distances.

The concept, which originated in the UK in the 1990s, refers to the distance that food is transported from the time of production till it reaches the consumer. It is an indicator of sustainability that pushes for local production and local consumption.

Els Wynen and David Vanzetti, in their paper, ‘No Through Road: The Limitations of Food Miles’, explain that the attraction of the food miles concept can be attributed to several factors – reduced transport costs; new technologies; and demand for out-of-season, processed (pre-packaged), and perishable products.

However, the concept is also considered to be flawed because it ignores the cost of production; the mode and scale of transport; and the importance of other inputs such as capital and labour.

The authors note that some product lifecycle studies have found that the greatest energy use occurs when moving the produce from the retailer to the consumer. Consumers often drive an empty car to a shop, then drive home with 5-10kg of groceries in a one-ton vehicle. The energy use per kilogramme is greater than the cumulative production and distribution costs up to that point.

In his paper, ‘Privileging Local Food is Flawed Solution to Reduce Emission’, Christophe Bellmann of the Hoffmann Centre for Sustainable Resource Economy explains how the concept of food miles is often invoked to restrict trade and support locally-produced food over imports. In this sense, it can be viewed as a trade protectionist measure to protect local farmers from competition.

Eating local may not be the best way to reduce the carbon footprint. Bellmann notes that consuming local food may make sense initially in reducing the carbon footprint and helping to generate employment. But this often ignores the emissions produced during the stages of production, processing and storage.

The mode of transport and seasonality can affect outcomes as well. For example in the US, food items travel more than 8,000km on average before reaching the consumer. Yet transport only accounts for 11% of total emissions, with 83% – mostly nitrous oxide and methane emissions – occurring at the production stage.

Therefore, from an environmental perspective, it may be better to consume lamb, onion or dairy products transported by sea, because the lower emissions generated at the production stage offset those resulting from transport.

Consumers sometimes prefer travelling some distance just to get fresh produce. Bellmann explains how driving more than 10km to purchase 1kg of fresh produce will generate proportionately more GHG emissions than air-freighting 1kg of produce from Kenya.

Similarly, growing tomatoes under heated greenhouses in Sweden is considered more emissions-intensive than importing open-grown ones from southern Europe. In term of seasonality, placing British apples in storage for 10 months leads to twice the level of emissions than that of South American apples sea-freighted to the UK.

Today, the major challenge in food production is not just about meeting niche demand, but also about fulfilling the over-arching needs of society and the economy at large. For this reason, food trade corridors must remain open to ensure the continuous functioning of supply chains to feed the world.

This is certainly not the time for countries to act individually or to protect their own interest, as they work out the post-pandemic ‘new normal’ for economic sectors, including food production. Protectionist policies, tariffs and export bans should be avoided. Instead, health and economic well-being should remain a priority.

Belvinder Sron

Deputy CEO, MPOC