Opportunities for Malaysian exporters

July, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Markets

Palm oil is one of the main edible oils and fats consumed in China. In 2020, its market share registered 17% of overall oils and fats consumption, second only to soybean oil at 42%. Two main factors influence the country’s palm oil trade.

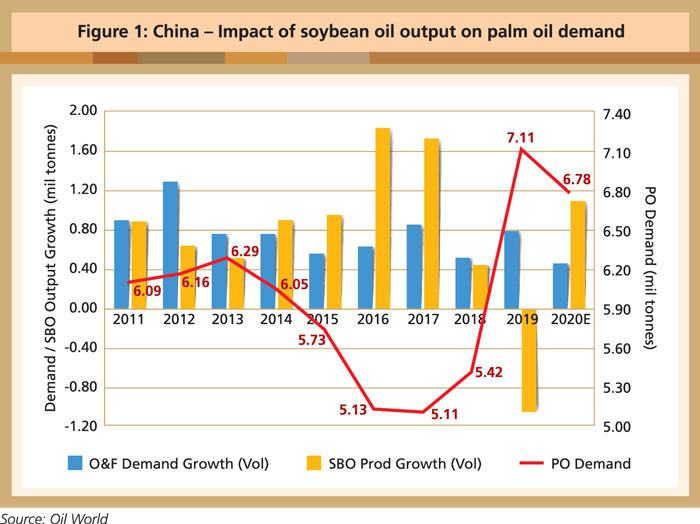

Firstly, intake of palm oil is affected by soybean meal demand to feed the growing animal husbandry sector. Higher soybean meal demand encourages local crushing. The resultant increase in soybean oil reduces the spread between soybean oil and palm oil, making palm oil less competitive. When soybean oil output is higher than the demand for oils and fats, palm oil demand will drop (Figure 1).

Secondly, there is a close competition between the two global palm oil suppliers (Figure 2). Indonesia’s lower price strategy and rising palm oil production have affected Malaysia’s palm oil market share in China in recent years. From a high of 41.5% in 2015, the Malaysian Palm Oil (MPO) share fell to 30.2% in 2019.

In 2020, however, the MPO market share in China rebounded to 41.8% because of reduced exports by Indonesia. The volume dropped by 1.5 million tonnes (28.2%) to 3.8 million tonnes, as Indonesia began implementing its B30 biodiesel mandate with effect from Jan 1.

In addition, Indonesia’s palm oil production dipped by 2.1 million tonnes to 42.2 million tonnes due to the lag effect of drought from July to September 2019. The average monthly rainfall then was 57.3mm, or 35.4%, lower than the 88.7mm recorded over the same period in 2018.

Promoting MPO

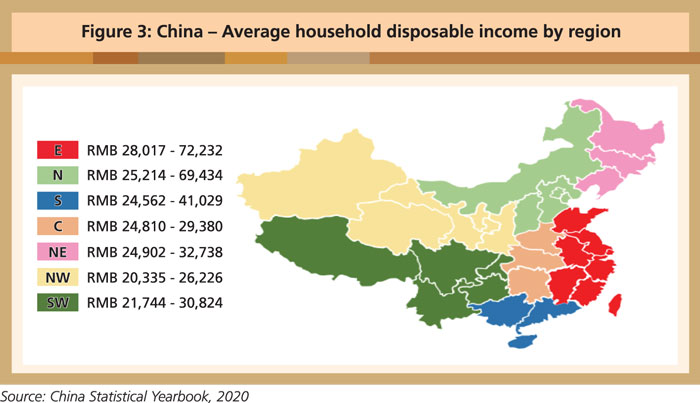

China’s strong economic development remains the key in strengthening the position of MPO. Malaysian exporters should move quickly to take advantage of the resulting changes in consumer demand, higher disposable incomes and impact of urbanisation.

Focusing on product differentiation and strategic partnerships will help Malaysian exporters to ensure long-term demand for MPO products. For instance, the use of palm oil in interior regions such as Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu and Shaanxi is confined to packed fats like shortening for frying. With the expansion of the cattle industry in these regions, there is scope for palm kernel cake to also make an impact.

At the same time, popular tourist destinations like Kunming, Chengdu and Xi’an – which have higher growth in the hotel, restaurant, café and confectionery sectors – offer much potential to improve the sale of palm oil for food.

However, the high cost of transporting palm oil products from coastal ports to inland regions currently impedes sales. Most of China’s interior is served by conventional railway networks. As a result, additional processing and storage facilities would be required to support the expansion of palm oil sales.

Malaysian companies could therefore consider collaborating with Chinese partners to put in place effective logistics, distribution systems and manufacturing facilities. This effort could be strengthened by organising seminars to enhance awareness among small- and medium-scale food processors and distributors on the superior qualities and versatility of MPO applications. End-users also need to be educated on the health and nutrition attributes to motivate their use of MPO products.

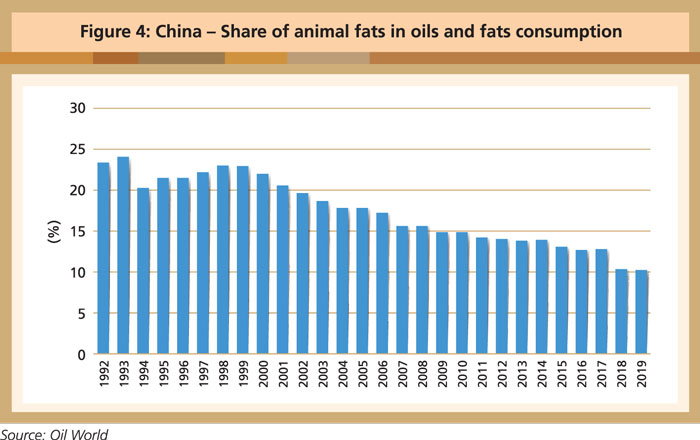

Changes in consumer behaviour in China have paved the way for increased use of palm oil products in recent years. Consumer perceptions about healthy foods have become a major trend in purchase decisions. Individuals are becoming more cautious about the oils and fats they consume, with more people moving away from animal fats due to health concerns.

As a result, the market share of animal fats is being filled by vegetable oils. Based on Oil World figures, animal fats accounted for only 12.7% of oils and fats consumption in 2019, after falling at an average rate of 1.7% per year since 2010. Palm oil players could capitalise on this situation to boost sales in the household sector, via endorsements by respected nutritionists and messages on social media platforms.

One product that could benefit from such focus is Malaysian Red Palm Oil, now that China has allowed the import of up to 20 tonnes of this product per consignment in packed form since mid-2020. Bulk shipments of any volume in flexibags and ISO tanks, for example, have been approved from March 1 this year.

Malaysian Red Palm Oil should be promoted as a healthy cooking oil. Avenues could be explored to blend it with other soft oils, and to encourage its use as an ingredient in bakery product formulations. Malaysian Red Palm Oil is rich in carotenoids (pro-Vitamin A) and Vitamin E. Its vibrant red-orange colour also makes the appearance of margarine, mayonnaise and ice cream more appealing without the use of artificial colorants.

The Covid-10 pandemic has prompted strong demand for hygiene products. Palm-based oleochemical derivatives can be used to make detergents, hand wash and sanitisers. Furthermore, growing demand for green products will compound the demand growth of oleochemicals.

Inner townships have grown rapidly in recent years as a continuing outcome of China’s reform programme. In rural areas, expansion has resulted in the emergence of a new growth market for palm oil products. According to the China National Bureau of Statistics, the rural population in 2019 was 551.6 million. As a result, for every 1kg rise in oil and fat usage per capita, there will be an increase of 551,620 tonnes.

In China, urban dwellers consume more oils and fats than those living in rural areas. Annual per capita intake in urban areas is 23-27kg; in rural areas, it is 15-18kg. Hence, there is a potential for 2.7-6.6 million tonnes of oils and fats to be added to the market, should per capita consumption among rural dwellers reach the level in urban areas. This can be achieved through the development of rural areas. Migration from rural areas is also likely to generate higher consumption of edible oils in urban areas.

Conversely, migration from urban to rural cities will have the effect of improving lifestyle choices and purchasing power per capita among rural Chinese. They will be encouraged to increase the use of refined oils. This will create opportunities to promote palm oil for blending with other soft oils, as it is competitively priced and a good frying medium.

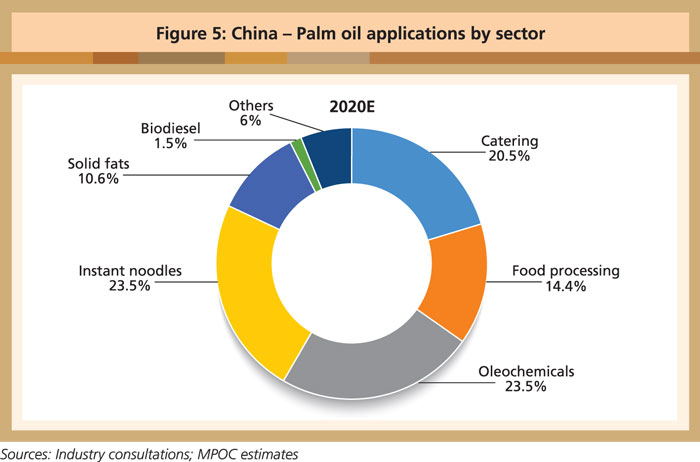

In China, about 75% of the palm oil is used by food-based industries including the catering, food processing, bakery, instant noodles and confectionery sectors (Figure 5).

RBD palm olein is popular in the catering and food processing sectors, although its use in frying instant noodles is dropping off. Most manufacturers are using palm oil instead. Even then, demand for instant noodles is limited in China because consumers prefer heathier food choices and can afford this because of better disposable income.

Oleochemicals command a good share of China’s non-food sectors. As such, Malaysia would benefit from stepping up its exports of oleochemicals and RBD palm stearin.

The bakery and confectionery sectors also hold out promise for enhanced palm oil demand in terms of solid fats. Despite being the second-largest bakery and confectionery market in the world, China’s per capita consumption is only 7.2kg, a far cry from 22.5kg in Japan and 40.2kg in the US. Euromonitor has forecast that the production of baked goods in China will grow by 53% between 2021 and 2025, or at an average of 10% per annum. This shows tremendous potential for higher uptake of palm-based products.

To avoid a price war with other suppliers of solid fats, Malaysian exporters will have to differentiate their products. Where possible, they should work with end-users to formulate bakery products that are unique to customer choices. In other words, Malaysian manufacturers should not merely be suppliers, but strategic partners of China’s bakery sector.

Lim Teck Chaii & Desmond Ng

MPOC China