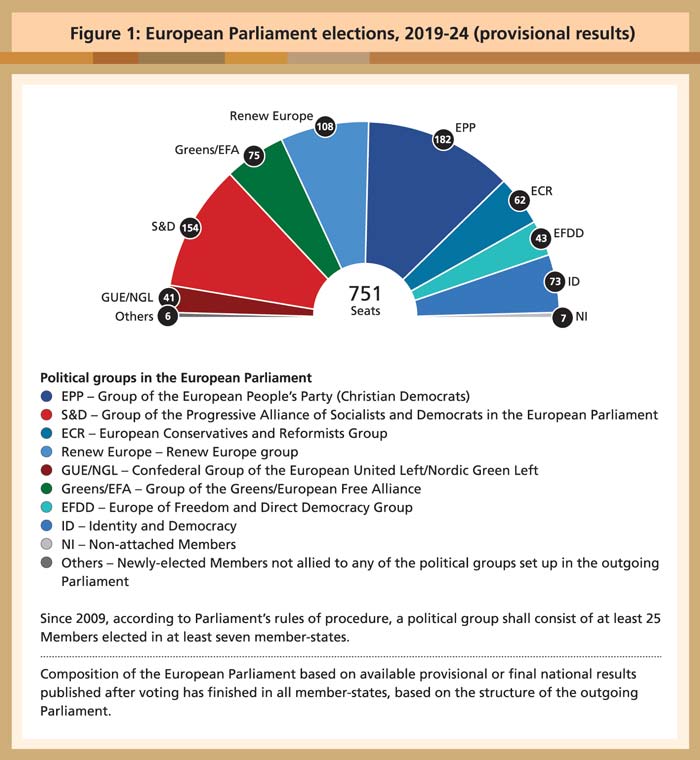

The European Parliament elections held in May saw the highest turnout of voters in 25 years and a major shift in power, as voters across the 27-member European Union (EU) chose the 751 Members who will serve for the next five years.

Two political blocs – the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats – lost their majority. However, the EPP remains the largest group in the Parliament. The Greens coalition party made significant gains as it increased its representation to 75, making it the fourth-largest voting bloc (Figure 1).

Source: European Parliament

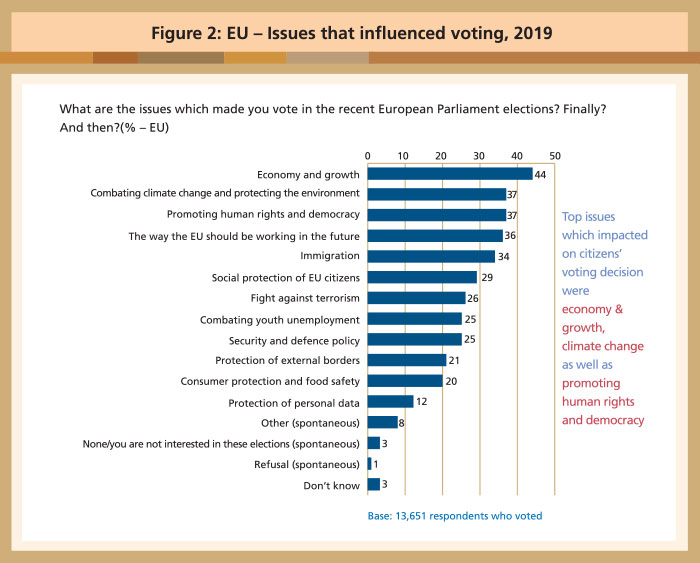

A study by the European Parliament shows that economic growth and climate change were the main issues that influenced voting decisions (Figure 2). It is clear that young Europeans are concerned about the environment and want politicians to do more to bring about climate change.

Source: European Parliament

The Greens’ focus on environmental issues will have serious implications for the palm oil trade. There will likely be more stringent environmental and energy polices in EU trade agreements. Market access is less of a concern for the Greens, who are keen on the EU using trade deals to export values on the environment and human rights, according to the UK’s Financial Times.

Ursula von der Leyen, a former German defence minister, has become the first female president of the European Commission (EC). She has pushed for a carbon-neutral continent by 2050, continuing the EC’s strategic long-term vision adopted in November 2018 for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate-neutral economy.

One prominent target is to curb greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity. Under the Paris Agreement, the EU has pledged to reduce emissions by at least 40% by 2030. The Greens may now lobby for this target to be raised through new legislation.

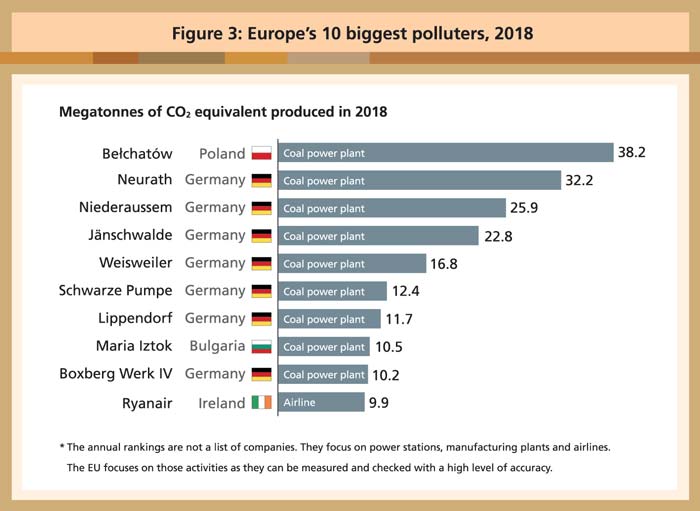

The British government was the first to announce legislation for long-term reduction in carbon emissions to net zero by 2050. Finland’s presidency of the European Council, which took effect from July 1, is also expected to focus on climate action. It could start by cleaning up its own backyard. For example, coal power plants in Germany are among the biggest emitters of carbon dioxide (Figure 3).

Source: European Commission

What lies ahead

On March 13, 2019, the EU chose to classify palm oil as an ‘unsustainable feedstock for biofuels’ in the Delegated Act under the revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED II). This places palm-based biofuels in the ‘high risk’ category. It means that palm oil cannot be counted towards the EU’s renewable energy targets.

Currently, rapeseed is the dominant biodiesel feedstock in the EU (44%), followed by palm oil (29%) and used cooking oil (15%). However, palm oil imports will be capped at the 2019 level and removed by 2030.

Malaysia and Indonesia have announced their intention to file a case at the World Trade Organisation on the basis that the Delegated Act is discriminatory and singles out palm-based biofuels.

Moving forward, discussions surrounding carbon taxes will also take centre-stage in the EU. The idea behind carbon border taxes is to introduce a levy on goods produced under conditions where excessive carbon is emitted. It is intended to push industries into producing goods in the least polluting way.

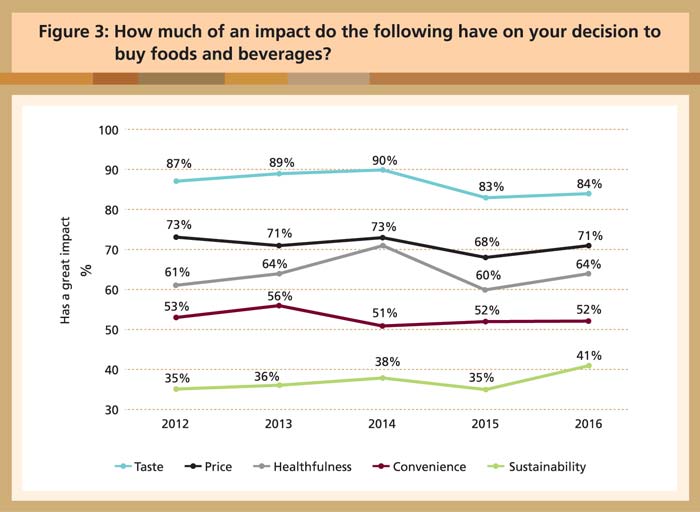

Carbon taxes on agricultural goods may have a positive impact in some respects, but the increased cost of production will lead to consumers paying higher prices – an issue that is already proving to be of major concern in the EU (see Box). Farmers, meanwhile, will incur a substantially higher cost to meet sustainability standards. This would also have an impact on hard-pressed moves to feed the growing global population.

The EU is bent on having its way on issues of sustainability in general and deforestation in particular. On July 23, the EC presented proposals to tackle global deforestation through ‘regulatory and non-regulatory measures’, to ensure that the EU consumes products ‘from deforestation-free supply chains’.

The proposal indicates that there is a need to strengthen standards and certification schemes ‘that help to identify and promote deforestation-free commodities’ such as coffee, cocoa, palm oil, soybean and timber.

The proposal on ‘Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests’ states:

Standards and certification schemes that help to identify and promote deforestation- free commodities should be strengthened through, among other things, studies on their benefits and shortcomings and by developing guidance, including assessment based on certain criteria to demonstrate the credibility and solidity of different standards and schemes. Such criteria should address aspects such as the robustness of the certification and accreditation processes, independent monitoring, and possibilities to monitor the supply chain, requirements to protect primary forest and forests of high biodiversity value and promote sustainable forest management.

Does this mean that current palm oil certification schemes will not be automatically accepted, but will have to be evaluated to demonstrate their credibility?

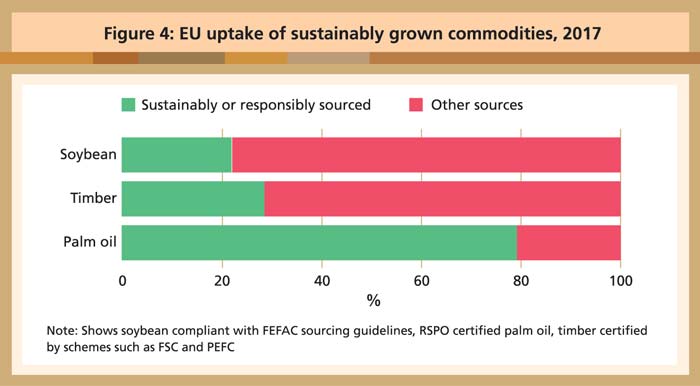

The palm oil industry has already embraced sustainability through the RSPO, MSPO and ISPO certification schemes. A report by the Netherlands-based IDH (The Sustainable Trade Initiative) states that palm oil has made remarkable progress with 74% of Europe’s imports being deemed sustainable. In contrast, very little of the soybean imports (22%) was sustainably sourced by the region’s food industry in 2017 (Figure 4).

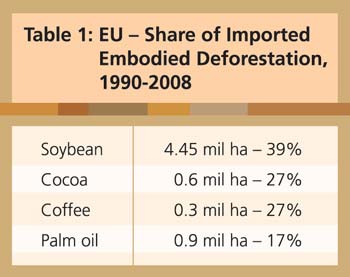

Source: Feasiblity study on options to step up EU action against deforestation

The EU has shown little disquiet to date over the production of soybean, cocoa and coffee, all of which have a higher deforestation footprint than palm oil in percentage terms (Table 1). Previous studies have proved that soybean is the second-largest agricultural driver of deforestation after the cattle sector.

Source: MPOB – data as at Feb 18, 2019; subject to revision

Yet, the EU has struck a political deal with American President Donald Trump, declaring US soybean as ‘sustainable’. In exchange, Europe has been promised zero tariffs on German cars and steel.

The EU’s stance on green issues would have credibility if it purchases the sustainably-produced palm oil that is already available, instead of constantly devising ways to prevent the industry from retaining its foothold in the region’s markets.

Factors Influencing Food Purchases in the EU

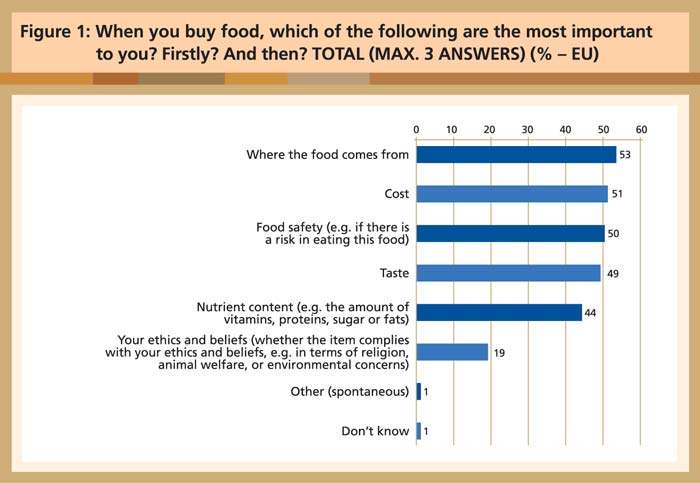

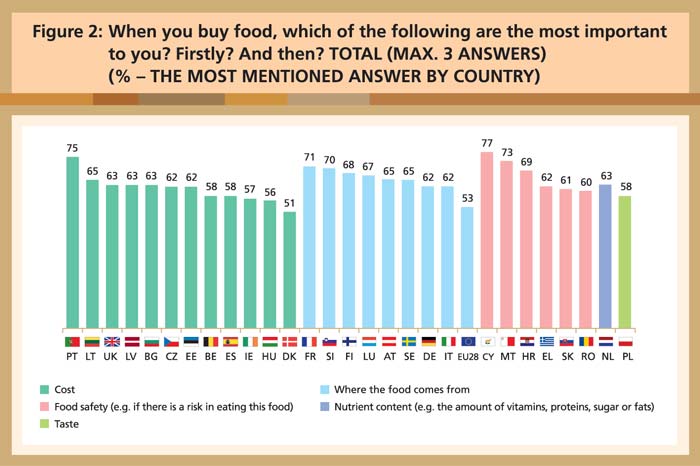

A Eurobarometer survey, commissioned by the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) to provide insight into Europeans’ overall interest in food safety, has indicated that where the food comes from (53%), the price (51%) and safety (50%) were the main considerations behind food purchases.

With climate change taking centre-stage in Europe, one would have expected consumers to be highly concerned about the environment. Surprisingly, this is not the case. Environmental concerns ranked the lowest in importance (19%) in the survey (Figure 1).

Source: Food safety in the EU, EFSA Report, June 2019

Source: Food safety in the EU, EFSA Report, June 2019

Source: Statista 2019

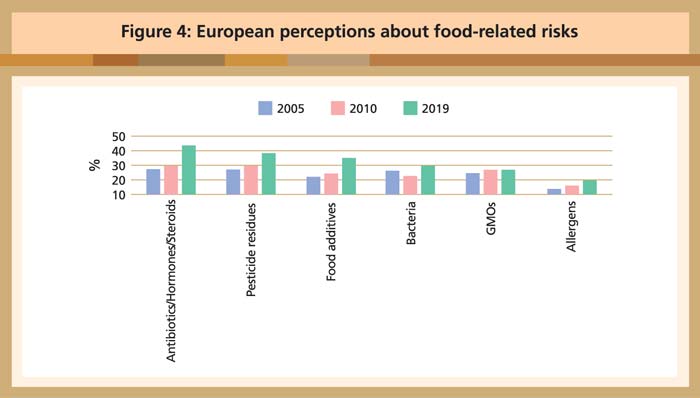

Ag Perspective has reported that, based on 14 years of EFSA public opinion surveys, there has been a 62% increase in concern about the use of antibiotics, hormones and steroids in agricultural products. Almost half of those polled are troubled about this, while around a quarter of Europeans rank genetically-modified organisms as a worrisome issue (Figure 4). There has also been a 63% rise in fear of food additives and a 44% jump in concern about the use of pesticides.

Source: EFSA/Eurobarometer

Belvinder Sron

Deputy CEO, MPOC