The emergence and presence of numerous sustainability benchmarks and standards for palm oil intensify the need for the sector to transform itself so that sustainable practices become institutionalised over time.

Having more references for sustainable palm oil raises awareness of sustainable development. If you look at palm oil producers, especially in Malaysia and Indonesia, they already know about the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and now with Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) and Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO), even more people, in particular, the small growers and the smallholders know about sustainable palm oil. The permeation and influence of the message of sustainable palm oil has risen more than ever before in these two major producers, who account for nearly 85 per cent of the global production.

These emerging national standards are in reality each country’s own definition of sustainable palm oil, but that does not mean they should be divergent or contradictory.

DEVELOPING A CREDIBLE FRAMEWORK

Perhaps, palm oil-producing nations could follow the lead of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), a non-profit organisation that encourages responsible management of the world’s forests. The FSC was the model for most Roundtables in the world today and the first standard that involved all stakeholders in the supply chain of timber.

It developed standards that incorporated social and environmental issues and today, everyone in the timber industry uses FSC as a benchmark. As a result, multiple national timber standards have emerged, claiming to address the same issues as the FSC, which has gone from strength to strength. Today, the vast majority of paperbacks you read are made from FSC-certified timber.

As for crude palm oil, around 19 per cent of the world’s production is RSPO-certified, and that is in just eight years. And like the RSPO, which has its fair share of critics, the national standards have come under the spotlight.

The questions swirling around in the industry include: Will each nation’s standard have credibility? Will it have adequate resources? How independent is the certification process? Is the standard based on full shareholder participation? How will it be enforced? What kind of sanctions will be taken against companies and smallholders that do not comply since the national standards are now mandatory? Is this an excuse for some producing nations to bypass the internationally recognised RSPO, which is seen as a foreign imposition? What about demand for CSPO? How will national standards assure the demand side?

All these are valid questions and the respective governments should respond to them with full transparency in order to create confidence among international stakeholders. Of course, there will be challenges. It is a big task for Indonesia and Malaysia to certify their 4 million odd smallholder units. Considerable resources are required. It is also going to be an issue for other major producing countries, such as Thailand, Colombia, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea and Latin American countries. But just because the journey is arduous, it does not mean it should not be taken.

Some attribute the emergence of these many references and standards to a lack of trust in the framework of the RSPO. One should angle this debate more constructively by drawing strength from the potential contributions these respective platforms can make to the sustainability agenda. And this must be done sincerely. The RSPO is actually a catalyst for more standards of this nature to be conceived – the ultimate aim here should be for the industry to produce sustainable palm oil.

ROLES PLAYED BY STANDARDS

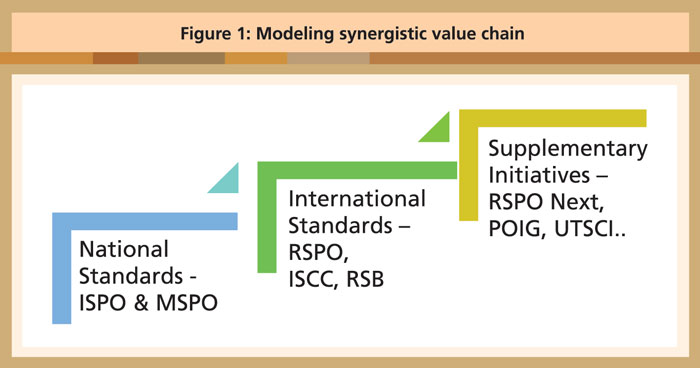

Although the many initiatives seem to have polarised the sector somewhat, hopefully it is only for the short-term. For the longer term, due to the complexity of the palm oil supply chain and the participation of such a massive number of players, including policymakers and governments, it is critical to ensure collaboration, if not integration, so that all these parallel schemes amalgamate at some point for maximum leverage and impact. This is how it is seen working.

National Standards

International Standard – the RSPO

Producing nations and governments should leverage on the RSPO as the next step in sustainability standards after the national standard has been achieved for countries that have such policies. This will ensure that producer countries upgrade from national to international sustainability standards.

Other initiatives

MARKET – THE FINAL ARBITER

In the beginning, the markets may be confused about which standard to adopt. Should they choose just one or more? The markets will have to do their own analyses of which platforms are prudent and what kind of assurance the consumers want. Indeed ultimately the markets will dictate which standards continue to exist for the long-term.

Interestingly in a recent comparative study of the many palm oil certification schemes, the non-profit organisation Forest Peoples Programme (FPP) concluded that the RSPO has the strongest set of requirements.

The study employed a comprehensive set of over 39 social and human rights indicators with six different themes and used the same yardstick to assess the various schemes against a range of criteria including:

Some of the most useful outcomes flow from the standard-setting processes, rather than the standards themselves. The necessity to debate what a standard is for, and how it should be developed, applied and verified, spurs engagement between a wide range of business, government, civil society and other stakeholders.

It is also important to be conscious of the maxim that standards are driven more by markets than industry or governments. This, of course, can make them much tougher to deal with than laws. The predictability factor can drop through the floor.

As always, if there is no demand, there is no reason for your product to exist, whether it is RSPO, ISCC or any other palm oil standard. But, it is not a matter of choice: these standards should be embraced at different levels, as shown in the diagram (Figure 1), and fully leveraged for their respective advantages as explained.

SUSTAINABILITY CHALLENGES

“Ours is a world of looming challenges and increasingly limited resources. Sustainable development offers the best chance to adjust our course” ….Ban Ki-Moon, UN Secretary General, COP 18 Doha

In the foreseeable future, demand for palm oil will remain constant. In fact, demand is very likely to increase, given higher consumption in the developing countries, thanks to growing populations and affluence.

The greatest barrier to the growth of the palm oil sector will be lack of awareness and misconstrued messages arising from initiatives promoting the banning of palm oil altogether. There will also be a significant impact from government policies. For example, at the time of writing this piece, the European Parliament is poised to endorse a legislative campaign to remove palm oil from the list of designated renewable fuels from 2021 over concerns about the environmental impacts. Camouflaged in arguments over deforestation and Indirect Land Use Change (ILUC), the resolution is clearly aimed at supporting European oilseed-based biofuel, primarily rapeseed and sunflower that struggle to compete with palm methyl ester (PME) which is far more competitive.

There has also been a proliferation of “No Palm Oil” labels on food products in Europe and elsewhere. Law does not require them nor do they provide any useful information to the consumer. They are there for one reason: to imply that because a product does not contain palm oil that product is somehow nutritionally or environmentally superior. These are the beginnings of a series of challenges that palm oil will face in some mature markets.

When a company does not use or decides to stop the use of palm oil in its products, most of time, it means that the product contains an alternative vegetable oil or fat. Concerns about environmental damage are prevalent with regard to the cultivation of any monoculture crop. Shifting to other vegetable oils will most likely increase the adverse environmental impact of edible oil production since the alternative crops will require five to eight times more land for the same amount of output compared with palm oil.

CONCLUSION

Oil palm cultivation is an important contributor to addressing dilemmas which we confront globally, such as poverty alleviation and food security. Oil palm is grown in some of the poorest nations in the world and over 50 per cent of the cultivators are small farmers and communities that are highly dependent on the crop for their livelihoods.

As the most widely-produced and traded oil seed crop and as one of the lowest-priced vegetable oils, sustainable palm oil helps to ensure world security in vegetable oils, stability in pricing and also provides a guarantee of sustainability. Supporting the sustainable production of palm oil is a far more constructive approach than simply boycotting palm oil.

It is therefore not only desirable, but also critical that all players in the palm oil supply chain, including regulatory and government representatives, rise to meet these challenges through accessible discussions and the forging of strong alliances and partnerships rather than working in silos.

The trajectory for the sustainability of the palm oil sector must be clearly carved out. Compromising the delivery of sustainable palm oil should not be an option.

M R Chandran

Advisor

Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil

Source: The Planter, Kuala Lumpur, 94 (1104): 175-179 (2018)

This article is reproduced with permission of ‘The Planter’ and the Incorporated Society of Planters.