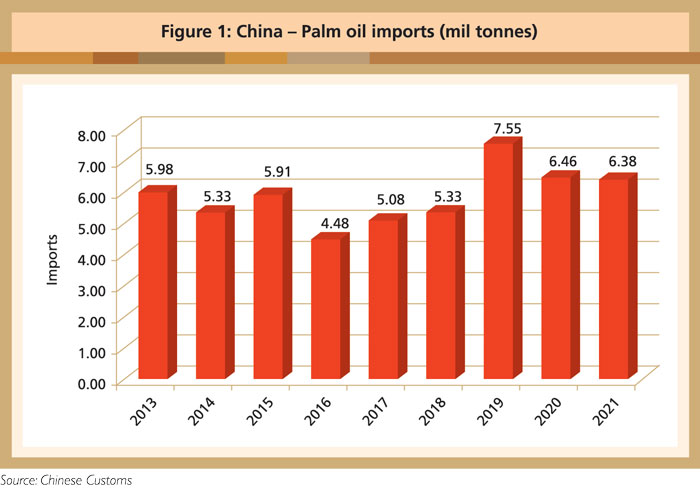

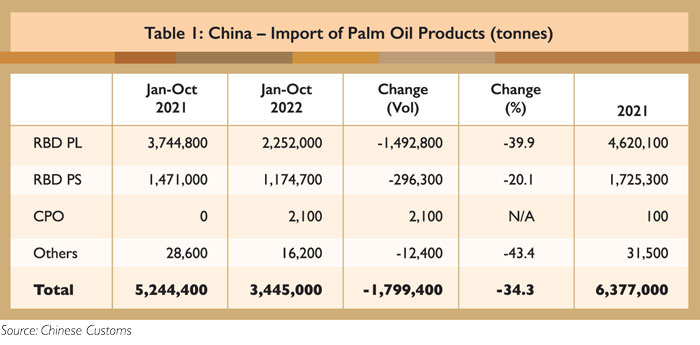

China’s palm oil imports recorded a drop from January to October 2022. The volume shrank by 1.8 million tonnes compared to the same period in 2021, although the deficit is expected to slightly narrow by 100,000 tonnes by end December.

Both RBD palm olein (PL) and RBD palm stearin (PS) recorded a significant decline in volume (Table 1). The import of RBD PS up to October 2022 was lower by 296,300 tonnes (20.1%) over the comparative period. However, if the intake of hydrogenated vegetable oils (HVO) is taken into account, the import of RBD PS – a feedstock for oleochemical production – has not dropped by too much.

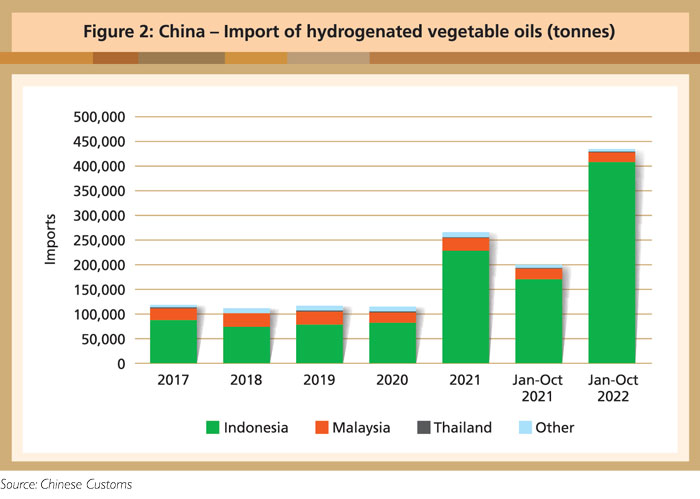

According to Chinese Customs, the import of HVO rose tremendously in 2021 and remained significant in 2022. In 2021, HVO imports more than doubled that in the previous year (264,900 tonnes vs 114,900 tonnes); up to October 2022, imports jumped by 234,600 tonnes against the 200,000 tonnes recorded from January to October 2021.

This was closely related to the change in Indonesia’s export duty structure on palm-based products in 2021. It favours the export of downstream palm-based products through very competitive prices, including hydrogenated palm stearin (HPS).

At the same time, the import of HPS in China is exempted from import duty under the ASEAN-China FTA, in contrast with the 2% imposed on RBD PS. Some importers and fatty acid producers in China therefore switched from RBD PS to HPS, to enable the local industry to lower the cost of production and compete with imported fatty acids.

China’s HPS imports amounted to 320,000 tonnes from January to October 2022, up by 235,000 tonnes against the same period of 2021. This means that demand for RBD PS or HPS as feedstock for fatty acid plants only dropped by an estimated 61,300 tonnes up to October 2022.

Imports of palm kernel oil in the January to October period declined by 114,300 tonnes (23.8%) over the comparative period. Although coconut oil imports increased by 50,000 tonnes, the net import of lauric oils was lower by 64,300 tonnes (10.4%). Unlike RBD PS, which is mainly used in oleochemicals production in China, 50% of the lauric oils are used in the food sector as specialty fats; the balance is used primarily in fatty alcohol production.

Performance of products

Stearic acid

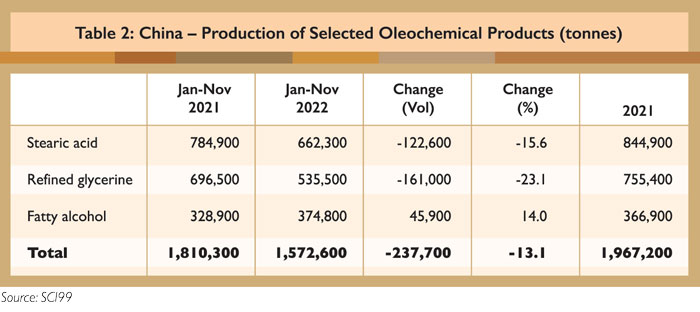

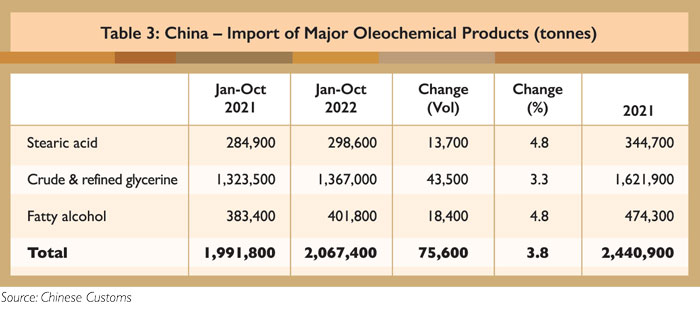

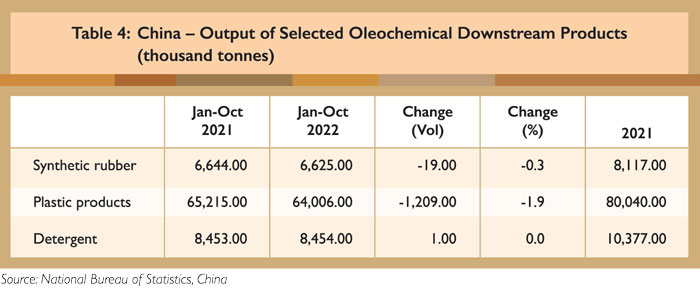

Overall supply of stearic acids in China declined in 2022, due to a drop in local production. The production data (Table 2) and import statistics (Table 3) show that demand for this product was stagnant or lower compared to 2021. It also explains why imports of RBD PS and HPS have dropped up to October 2022. Lower demand for stearic acid in 2022 was mainly due to the decline in the production of synthetic rubbers and plastic products; stearic acid is one of the key raw materials in this sector (Table 4).

As the auxiliary raw material in both PVC and synthetic rubbers, stearic acid accounted for 1% of the raw materials used. The falling output of both downstream products means that demand for stearic acid had declined by about 12,000 tonnes up to October 2022. In addition, lower output of stearic acid was affected by high RBD PS prices in the first half of 2022; this led to smaller imports of RBD PS and HPS, as well as less interest in stearic acid production.

China’s property sector, which accounts for a quarter of the economic growth, struggled with defaults and stalled projects in 2022. This affected demand for synthetic rubbers and plastic products (mainly PVC), as these are two of the main construction materials used.

China’s National Bureau of Statistics states that the total new built-up area in the property sector declined drastically by 630 million sq m or 37.8% from January to October 2022 against the same period in 2021 (Figure 3). The drop was sharper than the annual decline recorded in 2021 (11.4%), and also marked a fall in building activity for the third consecutive year.

The reasons can be attributed to a slowdown in economic growth, and to the government’s move to restrict excessive borrowing by developers. The clampdown resulted in a drop in property sales and prices, and the suspension of housing construction.

However, with the rollout of what market analysts have described as the “most comprehensive” support measures by the Chinese government in mid-November, the property sector is expected to recover in 2023. This will lead to higher demand for building materials, including synthetic rubbers and plastic products. Hence, demand may improve for stearic acid and its raw materials (RBD PS & HPS) in 2023.

Fatty alcohol

Total supply of fatty alcohol increased up to October 2022, with output and imports up 14% and 4.8% respectively compared to 2021. The increase was primarily attributed to the stringent Covid-19 preventive measures put in place in China, with many cities having been either simultaneously or consecutively locked down since March. This triggered a surge in demand for sanitisers and detergent products for regular cleaning of compounds affected by residents or visitors who are Covid-positive.

According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the production of detergent was on par with 2021, up to October 2022 (Table 4), performing better than the demand from sectors related to stearic acid downstream products. Stronger demand for fatty alcohol also indicates that demand for lauric oils (PKO and CNO) in the food sector was lower in 2022 than 2021, compared to the non-food oleochemicals sector.

Glycerine

The slowdown in stearic acid output also meant a drop in the supply of glycerine, which is a by-product of the hydrolysis process. Refined glycerine can also be produced from refining crude glycerine imported mainly from Brazil, Indonesia and Malaysia. According to market information, the output of refined glycerine dropped by 161,000 tonnes (23.1%) from January-November, compared to the same period in 2021.

Although imports of glycerine (crude and refined) increased by 43,500 tonnes, this was not enough to offset the decline in output and signified that demand for glycerine was rather slow. A main reason for the decline in glycerine production was the sharp increase in the price of raw materials (RBD PS & HPS).

The decline in epichlorohydrin production was another reason for the slowdown in glycerine consumption in 2022. Epichlorohydrin accounted for 67% of the downstream applications of glycerine in China.

Epichlorohydrin is the raw material used in producing derivatives of chemical compounds to manufacture surfactants, plasticisers, emulsifiers and stabilisers; some of these are used for the production of detergent, plastic and synthetic rubbers. The drop in output of plastic products and synthetic rubbers – even as detergent production remained on par with 2021 – explains the lower demand for epichlorohydrin and, hence, the demand for glycerine in 2022.

Recovery in 2023

With China’s recent relaxation of Covid-19 preventive measures, economic activities are expected to recover progressively. Support for the property market is also expected to drive demand for stearic acid, glycerine and fatty alcohol. This will inevitably support feedstock such as RBD PS and HPS to satisfy production needs.

The expectation is for higher output and imports of oleochemicals, and imports of RBD PS and HPS; this will support the growth of palm oil consumption in China in 2023 from the second quarter. It is anticipated that Covid-19 infections could rise after preventive measures are lifted, and that this will temporarily affect operations in the manufacturing and service sectors. Once herd immunity is achieved, economic activities be will reignited fully, and lead to better demand for palm oil products.

Desmond Ng

MPOC China

The European Commission (EC) is preparing a new regulation to target products produced with links to forced labour. It will give the EU the power to introduce trade bans, cut off financing and apply other sanctions to those suspected of benefitting (even indirectly) from forced labour.

This is additional to current EU proposals – the Environmental Due Diligence rules published as part of the Deforestation Regulation; and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive.

The new regulation will be more aggressive and targeted at importing companies. It signals that they could face sanctions on labour or human rights related issues. However, it also strikes a fair balance between the need to eradicate forced and child labour – and the need to establish a fair legal framework that respects natural justice. Other EU institutions should support this position.

Companies and other stakeholders must have a channel for engagement before sanctions are applied: this is how real and substantive changes can be made. Taking an adversarial approach by treating the private sector as guilty by default, will not help. Practical solutions are needed; not grandstanding. The EC’s proposal broadly achieves this.

There is no perfect labour market, without risk of forced labour, either inside the EU or outside. The proposed regulation should therefore not be used as a trade barrier against exporting countries or targeted at commodities for political purposes.

The Malaysian palm oil sector recognises the need for continuous improvement, including identifying areas of potential weakness, and also enhancing monitoring and enforcement. The sector is cooperating with government entities, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), NGOs and others in this process. The EU should seek to become a cooperative partner in this process, and not produce a regulation that creates conflict instead of cooperation.

Key facts and data

Malaysian palm oil sector

In Malaysia millions of small farmers, and plantation employees work daily to collect, transport and process palm fruits. This has provided income, security and the hope of a brighter future for many in Malaysia, and elsewhere via remittances.

However, the sector is not perfect and we recognise this. Widespread claims of poor labour practices have been levelled by the US government and other parties. Some claims are grounded in facts; others are inaccurate. The labour situation in the sector is highly challenging; the palm oil supply chain is complex; unfortunately, at times, this has been open to exploitation by bad actors.

Migrant labour is a common feature of agricultural systems the world over. Whether in Europe, the US or in Malaysia, the need for labourers – who have economic and social needs – is a challenge for industries and governments.

Oil palm plantations in Malaysia are no different. They require a large labour force, due to the high productivity and high production levels of the crop. As a small, rapidly developing country, Malaysia’s domestic labour force cannot meet these needs. Migrant labour is therefore an important element for plantation companies and – especially – for the 300,000 small farmers who require assistance to work their land.

Strong governance and compliance protocols

The Malaysian palm oil sector is governed by a modern and strong regulatory framework:

Commitment to labour rights improvements

The Malaysian palm oil community understands that it must live up to global labour rights standards, if it is to continue to successfully serve customers in the Asia Pacific, India, Europe, US and Middle East, among other international markets.

This means that questions about labour rights raised by any government, must be considered as global questions. They resonate across the supply chain. The customers are global companies, with high labour rights standards that apply to all markets.

The Malaysian palm oil sector is determined to live up to this responsibility. It has in recent months instituted a series of commitments and action plans implemented by private growers and palm oil companies. These actions send a clear message to customers, governments and stakeholders that the private sector is committed to rectifying problems that exist.

Commitments implemented by the government and private sector:

The Charter affirms the commitment of members to respect labour rights, adopt responsible recruitment practices and provide good working and living conditions for workers. It commits all members to a binding set of commitments on labour rights, including:

The commitments in the Charter are based on several international guidelines and frameworks:

A key consideration must be whether issues are systemic, whether reforms are underway and ILO protocols are implemented, and whether national laws and industry policies include labour rights commitments. In Malaysia’s case, it is clear those commitments are in place.

Increasing standards and compliance protocols

The MPOCC has undertaken significant revisions to the MSPO standards; these were published at the beginning of 2022.

The standards revision process included a broader range of stakeholders than when the original standards were drafted. They included the Malaysian Trade Union Congress and the National Union of Plantation Workers. Their representation was vital to the process, and is in line with international norms on labour rights and representation, specifically a tripartite (government, union and employer) approach.

MSPO certification is mandatory for palm oil production in Malaysia. This is enforced via the criterion for organisations to be licensed under the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB), the national regulator. The revised MSPO requirements are designed to align with ILO norms on labour rights.

Importantly, the MSPO provides almost no exceptions for any participants in the supply chain, upstream or downstream. The only exception provided is for independent smallholders, i.e. those not part of an arrangement with a larger plantation company.

This is in line with the social and employment norms that are part of broader standards, such as Social Accountability standards.

Setting the record straight

Malaysia has been subject to misinformation on labour issues. It is important to correct these inaccuracies.

Multiple US government agencies have publicly released assessments, including criticism, of the labour situation related to Malaysia’s palm oil sector. These assessments are based on a variety of qualitative and quantitative sources. The sources themselves, and the data and evidence they present, deserve significant scrutiny.

Decisions are made based on these sources and their data, which affect millions of workers, as well as cost companies millions of dollars. The US government in general is transparent about much of its source material, which allows an independent assessment to be made.

The Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) has undertaken a close assessment of a number of the source materials cited by the US Department of Labour, US Department of State and the US Department of Homeland Security’s Customs & Border Protection.

This assessment of the materials reveals that much of the data provided by sources such as NGOs or petitioner organisations, are out-of-date (in some cases by almost 40 years) or are not applicable to the specific complexities of the Malaysian palm oil sector.

The US Department of Labour’s assessment of the palm oil sector relies on significantly outdated sources and datasets, and fails to take into account initiatives undertaken by the private sector in terms of preventative action.

The US State Department’s assessment similarly fails to acknowledge the work undertaken by the private sector to establish better practices and NGO collaboration, where government policies have not kept up to date with global benchmarks.

The presence of child labour in Malaysian oil palm plantations has been confirmed by the government; yet the incidence is relatively small, largely isolated to the states of Sabah and Sarawak. For the most part, it involves unpaid family members assisting parents and children in legal employment exposed to suboptimal conditions; there is no evidence of widespread or systematic or institutional forced labour of children.

The claims ignore two things:

Many of the claims against the industry regard unethical recruitment of workers – the industry has taken steps against this and is continuing to seek workable solutions.

There is a significant conflation of Indonesia and Malaysia in many of the source documents and data, which betrays a lack of understanding of the significant differences between the countries themselves, and their palm oil sectors.

Child labour appears to have greater weight than migrant labour. This is in line with both emotive campaign tactics and the priorities of government policies around the world in attempting to eradicate child labour (but does not align with the focus on Malaysia, where there is no evidence of widespread forced child labour).

There is reliance in several instances on reports by campaigning organisations that are explicitly opposed to palm oil cultivation in the region. Using such reports as source documentation is not serious public policy, given the pre-existing bias. This approach weakens the claim that actions taken are independent and evidence-based, and undermines the goal of rooting out forced labour.

It is apparent that many NGO reports used as ‘evidence’ in building a case against Malaysia are largely based on recycled claims or claims that are relevant to the palm oil industry across ASEAN, or different industry sectors in Malaysia.

Only 10 of the reports – spanning more than a decade – used informant interviews. The use of informants is common, but when reports are based on old claims and recycled information, the use of informants is not serious.

The bulk of the reports simply repeated claims from other sources. While this is not a suggestion that these non-primary reports are not credible, there are instances where reports that would be considered ‘high profile’ – such as those by Liberty Shared and EIA – are closer to advocacy documents rather than investigative or analytical documents.

MPOC

The EU has begun reviewing its revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) in view of expanded ambitions for its 2030 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction target, as well as its path toward climate neutrality.

On July 16, 2021, the European Commission (EC) had published its ‘Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Directive 98/70/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the promotion of energy from renewable sources, and repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652’ (RED III).

The Proposal is part of the EC’s ‘Fit for 55: Delivering the EU’s 2030 climate target on the way to climate neutrality communication’. The EC, the Council of the EU (the Council) and the European Parliament have begun formulating their positions to reach a commonly agreed text. As with current EU rules on renewable energy, RED III is poised to affect palm oil as a biofuel feedstock.

The EC has been pursuing a number of sustainability-related objectives through various initiatives and legal instruments. In December 2019, the EC had presented the European Green Deal, a set of policy initiatives with the overarching aim of making the EU’s economy sustainable and climate neutral by 2050.

On July 14, 2021, the EC had adopted the Fit for 55 Communication. This aims at providing a coherent and balanced framework for reaching the EU’s climate objectives. It also builds on policies and legislation already in place.

To achieve the objectives of the European Green Deal and reduce GHG emissions, the EU now intends to update RED II, notably by increasing the target of renewable energy sources in its integrated energy system.

Upcoming regulation

According to the EC, RED III pursues three overall objectives:

RED II established a common framework for the promotion of energy from renewable sources. It set a biding target of 32% for the overall share of energy from renewable sources in the EU’s gross final consumption of energy in 2030.

RED III would increase the binding target for renewable energy to 40%. However, it is anticipated that this target will actually be set at 45%, as proposed by the European Parliament and the EC’s REPowerEU plan, presented in May 2022.

Article 25 of RED II on ‘Mainstreaming renewable energy in the transport sector’ sets sub-targets for the share of renewable energy within the final consumption of energy in the transport sector. The EC’s Proposal introduces amendments to Article 25, which will be titled ‘Greenhouse gas intensity reduction in the transport sector from the use of renewable energy’.

The proposed text foresees to increase the level of renewable energy used in the transport sector by setting a 13% GHG ‘intensity reduction target’. The GHG emission reduction target is intended to make RED III compatible with the EU’s Effort Sharing legislation, which establishes binding emission reduction targets for sectors not covered by the EU’s Emission Trading System, such as transport.

In comparison to the EC’s Proposal, the Council proposes to provide EU member-states with an option on the transport sub-targets:

The European Parliament, meanwhile, proposes to set a binding target of 16% GHG reduction in the transport sector by 2030. The amendments it proposes to Article 25 also include the possibility of a revision of RED III by 2025, to assess the obligations set in paragraph one of Article 25.

Any revision would only be undertaken if it were needed to meet the EU’s international commitments for decarbonisation, or where a significant decrease in energy consumption in the EU justifies an increase of the obligation target and sub-targets.

Accelerated phase-out?

The EC’s Proposal for RED III contains amendments to Article 26 of RED II, which provides specific rules for biofuels, bioliquids and biomass fuel produced from food and feed crops, including oil palm. The amendments aim at reflecting the new GHG reduction target set for the transport sector.

This means that the calculation of a member-state’s gross final consumption of energy from renewable sources would take into account the GHG reduction target – and not the minimum share of biofuels and bioliquids as well as of biomass fuels consumed in transport as established in RED II.

Article 26(1)(3) of RED II provides that member-states ‘may set a lower limit and may distinguish, for the purposes of Article 29(1), between different biofuels, bioliquids and biomass fuels produced from food and feed crops, taking into account best available evidence on indirect land-use change impact’.

The EC’s Proposal would not change this approach. Recital 31 of RED III reconfirms that ‘in order not to create an incentive to use biofuels and biogas produced from food and feed crops in transport, member-states should continue to be able to choose whether to count them or not towards the transport target’.

Thus, member-states will likely continue adopting legislation that excludes certain feedstocks, such as palm oil, from being counted towards the renewable energy targets or even from being used as a biofuel at all.

A worrying example lies in Belgium’s approach. From Jan 1, 2023, it will prohibit the placing on the market of biofuels and biogases based on palm oil or other products directly or indirectly derived from oil palm. From July 2023, it will also prohibit the placing on the market of biofuels and biogases based on soybean oil or other products directly or indirectly derived from the soybean plant. Rather than perpetuate discriminatory practices, the revision of RED II should address these unfortunate aspects of EU legislation.

Neither the EC’s Proposal nor the Council’s position on RED III modifies the rules related to high ILUC-risk and low ILUC-risk certification. However, the European Parliament proposes amendments regarding the phase-out of high ILUC-risk biofuels.

Article 26 (2) of RED II states that, for the calculation of a member-state’s gross final consumption of energy from renewable sources, ‘the share of high indirect land-use change-risk biofuels, bioliquids or biomass fuels produced from food and feed crops […] shall not exceed the level of consumption of such fuels in that member-state in 2019, unless they are certified to be low indirect land-use change-risk biofuels, bioliquids or biomass fuels pursuant to this paragraph’ and that from Dec 31, 2023 until Dec 31, 2030 at the latest, ‘that limit shall gradually decrease to 0%’.

The European Parliament proposes that RED III moves forward the phase-out of high ILUC-risk biofuels to the entry into force of RED III, expected in late 2023 or the beginning of 2024. This is particular worrisome for the palm oil industry, as this would do away with the gradual phase-out until 2030 and would lead to a de facto ban of palm-based biofuels well before then.

Additionally, the European Parliament proposes to add a sub-paragraph to Article 26(2) to state that, by June 30, 2023, the EC must submit to the European Parliament and to the Council ‘an update of the report on the status of worldwide production expansion of the relevant food and feed crops’.

The update must include ‘the most recent data from the last two years with regard to deforestation and high indirect land-use change risk feedstocks, and shall address other high risk commodities in the category of high indirect land-use change risk feedstocks’.

With respect to the Delegated Act setting out criteria for the certification of low ILUC-risk biofuels, bioliquids and biomass fuels and for determining high ILUC-risk biofuel feedstocks, the European Parliament states that ‘the maximum share of the average annual expansion of the global production area in high carbon stocks shall be 7.9%’.

The Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/807 currently sets this share at 10%. Therefore, the amendment appears clearly motivated to also phase out soybean as a biofuel feedstock, given that an 8% annual expansion into high-carbon stock land is attributed to the crop.

Used cooking oil (UCO)

A notable change proposed by the EC concerns the double counting system. Under RED II, UCO is considered to be waste-based and is double counted for the decarbonisation of the EU’s transport sector. For instance, if consumption of UCO amounts to 2%, it will be counted as 4% of total energy used in transport, providing an incentive to use such oils to reach the renewable energy targets.

Palm oil that has been used to fry foods can be converted for the production of biodiesel. In 2019, over 1 million tonnes of palm-based UCO were exported from Malaysia alone to the EU.

But in its Proposal for RED III, the EC eliminates the reference to ‘double counting’ with respect to advanced and waste-based biofuels. This removes the additional incentive and could discourage the use of UCO as a biofuel feedstock.

In the context of UCO, the European Parliament proposes to add Recital 38b: ‘Adequate anti-fraud provisions must be laid down, in particular in relation to UCO, given the widespread mixing of palm oil. As the detection and prevention of fraud is essential to prevent unfair competition and rampant deforestation in third countries, full and certified traceability of these raw materials should be implemented.’

In this regard, the European Parliament proposes to amend paragraph 3 of Article 30 on ‘Verification of compliance with the sustainability and greenhouse gas emissions saving criteria’. It states that ‘auditing shall verify that the systems used by economic operators are accurate, reliable and protected against fraud, including verification ensuring that materials are not intentionally modified or discarded so that the consignment or part thereof could become waste or residue’.

Discriminatory rules

The rules adopted under RED II and the EU’s Delegated Regulations discriminate against certain biofuel feedstocks, notably those not produced in the EU, such as palm oil.

Indonesia and Malaysia, as the world’s biggest palm oil-producing countries, have, therefore, embarked on dispute settlement proceedings with the EU at the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The two countries argue that the EU rules discriminate against palm-based biofuels. The revision of RED II would be the ideal opportunity to correct the discriminatory practices. Instead, the European Parliament’s proposal would make things worse.

Malaysia considers that the ILUC approach under RED II is inconsistent with the EU’s WTO obligations. Instead of accelerating the phase-out of ‘high ILUC-risk biofuels’, the EU should, in the spirit of the Paris Agreement, pursue a more coordinated, global approach to land-use change that would sustainably address global environmental problems.

Given the currently diverging positions, the European Parliament and the Council of the EU must now agree with the EC on a common text before RED III can be adopted. The inter-institutional ‘trilogue’ negotiations were scheduled to begin on Oct 6, 2022.

Malaysia must continue to engage with the EU and formally reiterate, both bilaterally and within the WTO framework, its special development, financial and trade needs as a developing country. It is highly dependent on the production and export of palm oil to the EU as a biofuel feedstock.

A single approach by the EU that does not recognise Malaysia’s efforts vis-à-vis sustainability, GHG emission reduction and the protection of high carbon stock land is not only discriminatory, but also profoundly unfair and counter-productive in efforts to curb climate change.

MPOC Brussels

While oil palm smallholders risk living in poverty, the US$282 billion palm oil industry creates huge profits for companies. The pivotal role of smallholders, currently contributing to about 30% of global production, is often overlooked in the sustainability agenda, as policies tend to focus on large industrial plantations. And with their contribution to palm oil production expected to grow, smallholders play an increasingly central role in rural economic development and preserving biodiversity.

With palm oil as a crucial ingredient in the diet of the poorest people on earth, and its widespread presence in products like margarine, shampoo and biodiesel, it’s here to stay. Supply chain-wide smallholder inclusion is crucial for sustainable palm oil production.

The first global Palm Oil Barometer by Solidaridad and smallholder producer organisations in Asia, Africa and Latin-America, gives a new perspective on the largely negative public debate around palm oil in western countries. This crop presents more issues and more opportunities than many people realise.

Deforestation and poverty are interlinked

Palm oil production features prominently in the media as a cause of deforestation, biodiversity loss and climate change. However, by isolating its impact on the environment from the poverty crisis, to which it is directly linked, it is easy to overlook the vital role smallholders play in palm oil production.

Although the image of large companies growing vast expanses of oil palm as a monoculture holds true, more than three million smallholders and their families produce roughly 30% of the world’s palm oil. And a multitude of workers find jobs in oil palm cultivation. In Indonesia alone, there are around 16 million workers in the sector, the majority of whom are employed by smallholders. The contribution of smallholders in the overall supply of palm oil is only expected to increase, as industrial-scale companies are forced to limit expansion due to zero-deforestation commitments.

Shatadru Chattopadhayay, Managing Director of Solidaridad Asia, reflects: “Smallholders produce not even 2% of certified sustainable palm oil on the market, while contributing 30% of the world’s supply. Governments and businesses must make smallholder inclusion part of their sustainability criteria.”

Smallholders do not get their fair share

Smallholders generated US$17 billion of the palm oil industry’s US$282 billion turnover in 2020, yet many did not earn enough to cover their family’s essential living costs. Despite this, many smallholders prefer growing oil palm to other crops like rubber or coffee, because they earn a higher and more consistent income throughout the year. For many smallholders, growing oil palm gives them better prospects and alleviates poverty.

Multiple factors can influence a farm’s profitability, including its size, labour and fertiliser costs, market access and prices. Volatile market prices squeeze smallholder margins that are already narrow.

“It’s getting more and more difficult for farmers with all these changes in the prices. Some feel as if 50% of their livelihood has been lost as the prices of the fresh fruit bunches have been slashed and, at the same time, the price of fertilisers and pesticides have risen by more than 100%,” said Valens Andi, head of a farmers’ cooperative in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, to Al-Jazeera.

Faced with these precarious conditions, many smallholders are unable to invest in farm-level innovations or adhere to sustainability standards. By 2030, smallholdings will account for around 60% of Indonesia’s oil palm area. Supporting these smallholders to produce sustainably will be a key challenge in the coming years.

Fair value distribution is at the heart of sustainable palm oil production

At the other end of the chain, food manufacturers, consumer goods companies and retailers take 66% of the gross profits on palm oil in food, household and body care products. The focus on cost-cutting to optimise profits contrasts starkly with individual companies’ sustainability commitments, as well as the global climate and UN Sustainable Development Goal agendas.

The concern is that global palm oil buyers show little willingness to compensate small producers for operating sustainably, for example, by paying a fair price and investing in long-term trading relationships. A fairer value and risk distribution across the palm oil value chain enables farmers to both produce sustainably and make an income that sustains their family’s livelihood.

Stop boycotting and start investing in good palm oil production

Smallholder interests are not only overlooked in the value chain, but their role and interests are also ignored in the public debate. Campaigns by NGOs and commercial brands call for a palm oil boycott to combat biodiversity loss. Many academics and conservation organisations agree that banning palm oil would simply shift the problem elsewhere, threatening other habitats and species.

Oil palm is far more productive than any other vegetable oil crop. On average, it is five times more productive than soybean. Replacing oil palm with alternatives would intensify the battle for scarce farmland. Instead of boycotting palm oil, the industry should invest in sustainable production by smallholders.

Bring smallholder voices to the fore

Farmers’ organisations should play a key role in the debate on the future of palm oil. Focusing on fair value distribution and minimising environmental degradation is key. The private sector and governments need to move from technical assistance to programmes that address the structural disadvantages at smallholder level. Solutions will not be the same everywhere and have to be found in a combination of voluntary and mandatory approaches.

Heske Verburg, Managing Director of Solidaridad Europe, recommends: “Companies and governments in consuming and producing regions [should] include smallholders’ interests when developing and implementing policies. The EU should ensure that smallholders will be supported to meet the requirements of the EU Regulation on deforestation-free products and, in partnership with producing countries, tackle the root causes of deforestation, including poverty.”

Source: Solidaridad Network

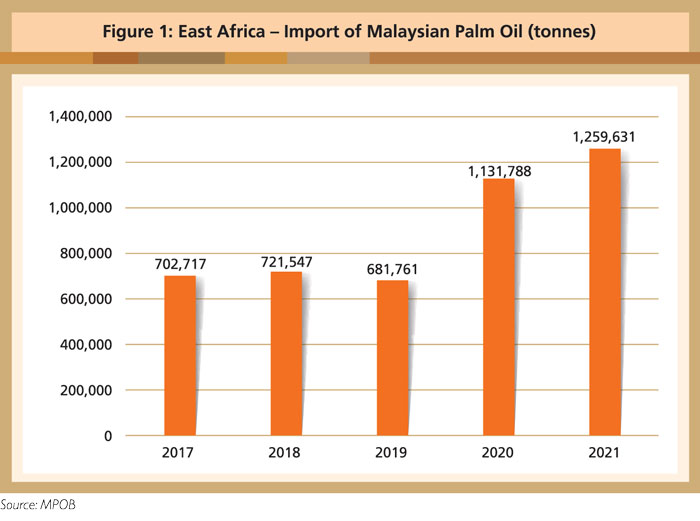

Sub-Saharan Africa, with a population of about 1.2 billion, is a net importer of palm oil, although several countries in the region are themselves producers. Demand for Malaysian Palm Oil (MPO) has been particularly strong in east Africa, which absorbed 1.3 million tonnes in 2021 – an increase of 11% compared to 2020 (Figure 1). Palm oil is mainly used in Fast-Moving Consumer Goods applications, such as cooking oil, baking fats and food products.

Key markets in region

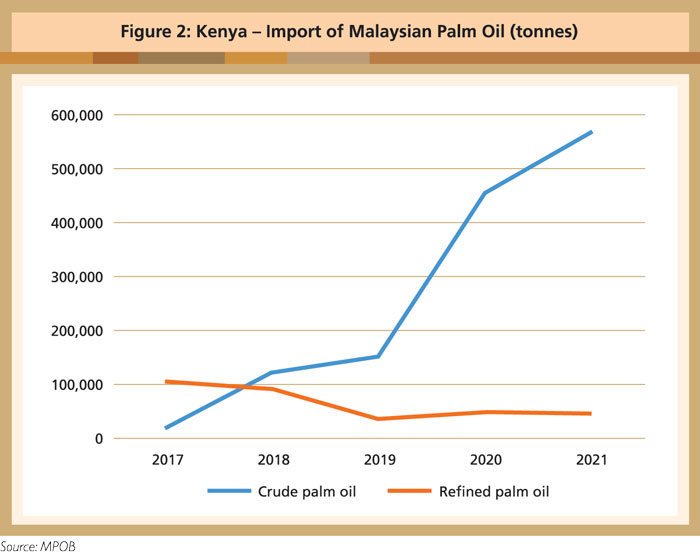

Kenya is a net importer of oils and fats. Palm oil accounts for more than 90% of the oils and fats it consumes. In 2021, it absorbed 780,000 tonnes of palm oil, of which 670,000 tonnes were from Malaysia.

CPO has replaced RBD palm oil as the main MPO product since 2018 (Figure 2). Imports of RBD palm oil have declined due to Kenya’s enforcement of a requirement for mandatory fortification of vegetable fats and oils with Vitamin A. In addition, demand for CPO has been boosted by the zero import tariff. Mombasa port remains a major re-exporting hub for palm oil, especially to landlocked countries such as Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Tanzania is another major regional market for MPO. In 2021, it imported 204,085 tonnes, which made up about 43% of its palm oil import volume. On July 1, 2022, Tanzania lifted its high 25% import tariff on CPO. This had been imposed in 2018, when there was zero import tariff in most east African countries. It had led to unattractive prices and loss of markets in neighbouring countries, as Tanzania is also a re-export hub. With the lifting of the import tariff, palm oil trade is expected to pick up.

New infrastructure projects

Improved roads, ports and logistical services have aided the movement of goods in this region. Over the past decade, international investors – particularly from China, the US and France – have entered the African market. Countries like Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria and South Africa are growing into economic powerhouses.

In recent years, east Africa has prioritised the improvement of cross-border and transport infrastructure. The EAC Secretariat completed 1,700km of road projects from 2012-20 to link Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi.

A mega project –Tripartite Transport and Transit Facilitation Programme Eastern and Southern Africa – is due to be completed by 2030. The countries in these regions will then have harmonised road transport policies, laws and regulations, and better road infrastructure.

China, which has been Africa’s biggest economic partner since 2000, is operating its Belt and Road Initiative here as well. The focus is on the development of roads, railways and ports across multiple African nations.

The port of Mombasa, one of the busiest in the region, has been going through phases of major reconstruction to accommodate vessels with a bigger capacity. Other ports along the northern corridor have been undergoing a revamp as well.

DP World Kigali in Rwanda is the first inland dry port in east Africa that has access to the port of Mombasa in Kenya and port of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. It secures two main trade gateways to the sea, and has an annual handling capacity of 350,000 tons of cargo and 50,000 TEUs. It also connects Rwanda via road to neighbouring landlocked countries such as Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi.

DP World Kigali has reduced the cost of logistics services, including long-haul transportation. It offers efficient operations, automation, an Inland Container Terminal and warehousing facilities. It has also served as a one-stop centre to connect all logistics players since operations began in 2018.

In 2021, DP World Maputo launched its first dedicated logistical train services between Maputo in Mozambique and Harare in Zimbabwe. The service is expected to reduce transit times for goods delivery between the two countries.

All these improvements have also helped ease the movement of MPO in the region.

MPOC Sub-Saharan Africa

MPOC’s signature event, the Palm Oil Trade Fair & Seminar (POTS), was held in Manila in The Philippines on Aug 17, 2022, for the third time since the global series was instituted. Eight papers were presented, while a special panel session discussed food security issues.

A concurrent trade fair and exhibition drew manufacturers and suppliers of palm oil and ancillary products from Malaysia. This served as a platform for the exhibitors to interact directly with buyers and customers in The Philippines. A Biz Match session enabled buyers and sellers of palm oil and derived products to discuss trade opportunities.

The event was opened by the Hon. Datuk Hajah Zuraida Kamaruddin, Minister of Plantation Industries & Commodities, Malaysia, who delivered the keynote address. MPOC Chairman Datuk Larry Soon @ Larry Sng Wei Shien welcomed the dignitaries and participants. Edited versions of their speeches follow.

“Malaysia and the Philippines have a record of strong trade relations. In 2021, total trade was recorded at US$7.3 billion, making The Philippines the 15th largest trading partner of Malaysia. In the first half of 2022, trade stood at US$4.7 billion, already indicating a significant improvement.

POTS Philippines provides a valuable platform for those in the oils and fats business, particularly palm oil, to explore business collaborations, opportunities and trade partnerships. The importance of The Philippines market for Malaysian Palm Oil (MPO) cannot be understated. It was the sixth-largest export destination for MPO in 2021, with the volume exceeding 580,000 tonnes and valued at almost US$600 million.

In 2021, the export of MPO and derived products was valued at US$24.7 billion. In addition, the industry provides employment to more than 1 million people. This indicates the importance of the palm oil industry in Malaysia’s economic development. The Ministry of Plantation Industries & Commodities – through its agencies, namely the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB), Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) and Malaysian Palm Oil Certification Council (MPOCC) – plays a vital role in R&D, marketing and promotion, as well as certification of sustainable palm oil.

The Philippines, which produces about 90,000 tonnes of palm oil, could learn from Malaysia in order to expand the industry. Malaysia has much to offer, especially in R&D, to countries that aspire to cultivate oil palm. I also believe that there are vast opportunities for the private sector in the two countries to redefine business approaches in forming strategic alliances, and to discover new ways to expand the market.

Apart from being the most affordable edible oil, palm oil is also used in the non-food sector, including oleochemicals and renewable energy. As such, we can say that palm oil is used in almost all the products consumed in our daily life.

However, palm oil has also become the subject of heavy criticism. To address these issues, we are working tirelessly with stakeholders within the country, as well as at international level through the Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC).

The most common allegations against the palm oil industry are about links to deforestation and forced labour. In this regard, we have engaged all relevant parties in discussion to resolve the issues amicably. Significant steps that have been taken are the establishment of a working committee between Malaysia and the US to address alleged forced labour issues; while a review panel has been set up under the World Trade Organisation to deliberate Malaysia’s complaint against the EU’s phase-out of palm oil.

To strengthen cooperation among palm oil producing and consuming countries, I’ve personally requested major importing countries to recognise our efforts in addressing these allegations. As a result, major consuming countries are now recognising the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil certification scheme. It ensures that MPO is produced through sustainable practices that conserve the environment.

Malaysia and Indonesia – via the CPOPC – have also established The Global Framework of Principles for Sustainable Palm Oil. This can be used as a common reference across different certification schemes applied primarily to palm oil production. It is also anchored in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. This is one tool that can be beneficial to the Philippines in developing its palm oil industry.

The industry is going through an exciting phase of high prices and strong growth in demand. If we commit to working together, we can overcome the challenges and reap huge benefits. Opportunities are waiting to be explored, especially in downstream lines with high value-added palm derivatives such as oleochemicals, pharmaceuticals, processed foods, specialty products and even consumer brands.

With that in mind, I encourage all participants to make the most of this event to explore joint investments which will enhance your business operations in the long run.”

“POTS has become a signature event in the palm oil industry calendar. The objective is to facilitate the marketing and trading of Malaysian Palm Oil (MPO) in the international market. POTS has grown to become an important platform for global oils and fats industry players to share the latest news and developments with their associates, counterparts and even competitors.

The Malaysia-Philippines POTS has been brought to Manila on the basis of it being the capital and business centre of the country. We have chosen the theme ‘Addressing Philippines Oils and Fats Diversity through Malaysian Palm Oil’, as it is reflective of the enormous opportunities afforded by the palm oil trade. These will drive the industry in both countries towards stronger trade partnerships and the cultivation of new ventures.

The rapid transformation of the global oils and fats market due to ever-changing trade policies, price volatility, weather uncertainties, more stringent sustainability agendas and increasing demand for food security, makes it imperative for the palm oil industry to constantly evaluate and improve existing strategies.

We must ensure that we keep pace with these challenges and changes by adopting new processing technologies, improving product development, promoting product differentiation and providing high service standards and traceability in the supply chain. Malaysia, as a pioneer and market leader in palm oil development, has been proactive and innovative in differentiating ourselves from our competitors.

In the first half of 2022, Philippines imported 340,000 tonnes of palm oil from Malaysia, an increase of almost 50,000 tonnes or 17% compared to the same period in 2021. This can be attributed to factors such as the competitive price, increase in population and robust economic growth. It is worth noting that this volume was achieved despite facing competition from other oils and fats, as well as competition from other palm oil producing countries.

There is a wide range of applications for palm oil. Its role in The Philippines is mainly to serve food demands. Asian cooking requires that the oil used is stable at high temperatures, does not impart flavour and, most of all, that it is healthy. In this aspect, palm olein is the preferred frying fat in Asia because of its high oxidative stability and low tendency to develop rancidity during prolonged storage of fried products.

Although palm oil is mainly used in food manufacturing in The Philippines, there are other areas where its use can be expanded. These include confectionery items such as chocolates; bakery items such as cookies and bread; nutraceutical derivatives such as Vitamin A beta carotene and Vitamin E tocotrienols, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals.

We see strong demand here for the use of oleochemicals, especially for personal care and household cleaning products. Besides being biodegradable, palm-based oleochemicals are available in many different formulations which give large manufacturers a wide selection of raw materials to incorporate into the final product.

The Philippines also has a biofuel development plan – the DOE’s Biofuels Roadmap 2018-40, which intends to increase the country’s biodiesel requirement to 5%. I am convinced that palm oil can be the alternative biofuel feedstock. Palm-based biodiesel has lower carbon emissions compared to petroleum diesel. It is superior to soft oil-based biodiesel as it is produced in a more sustainable manner, with lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Through today’s dialogues and interactions between players in The Philippines’ oils and fats market and MPO industry stakeholders, we are hopeful that agreements can be reached in addressing the supply-demand aspects of palm oil trade.

The agenda is designed to help you identify the biggest opportunities, crunch numbers and see what prospects can be explored. In this regard, I am glad to see an impressive representation from both the public and private sectors of Malaysia and The Philippines, to support the push towards greater trade and use of palm oil.”

Like other nations, the US has been moving forward with its recovery process from the chaos created by the Covid-19 pandemic, which damaged global supply chains and wrecked the economy.

The initial stage of the pandemic in 2020/21 had put a slight dent in oils and fats demand and supply, mainly due to disruptions in logistics and lower consumption. The preventive measures put in place by the US federal and state governments, including travel restrictions, social distancing and stay-at-home orders, affected demand from the food and the hotel, restaurant and café segment.

However, the US government and the industry were quick to put in place remedial initiatives to address issues related to supply chain and logistical support, vital in the recovery efforts to improve oils and fats demand and consumption. The Senate also approved a stimulus package designed to jump-start the economy.

The US is one of the world’s largest markets for vegetable oils. It accounted for approximately 80% of the volumetric share in the North American vegetable oils market in 2021. The US dominates the regional market, owing to its high consumption and export of oils. The increase in demand for vegetable oils from the food service and food processing industries, coupled with demand growth in the convenience foods market segment, helped maintain steady growth in the oils and fats market. Based on the vegetable oils report, oils and fats are projected to record a compound annual growth rate of 4.9% from 2021 to 2027.

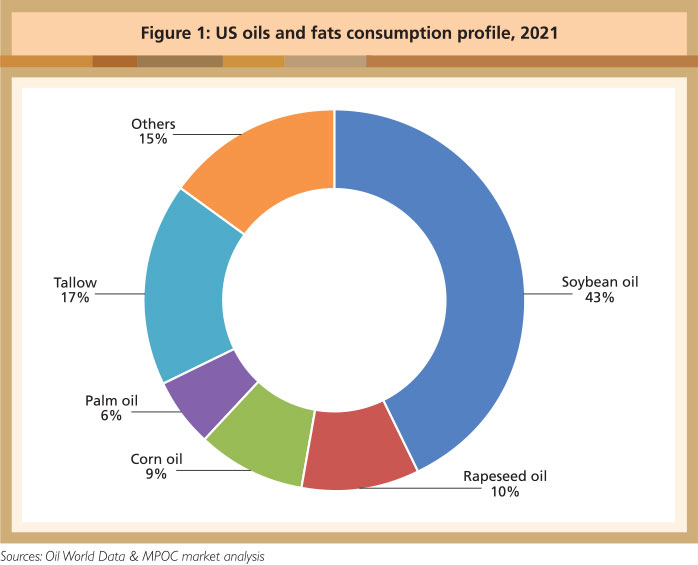

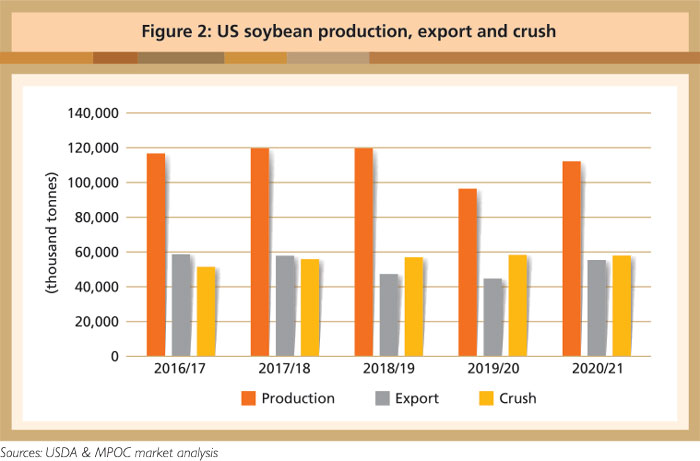

The US is also the largest producer of oils and fats in North America. Oil World data indicates that it produced 21.7 million tonnes of oils and fats in 2021. According to the US Department of Agriculture, soybean oil is by far the most widely produced and consumed edible oil domestically, mainly used for fast-food frying, addition to packaged foods, and feed for livestock.

In 2021, soybean oil constituted 52.6% of total oils and fats production, or about 11.3 million tonnes. Over the past three years, domestic consumption of soybean oil has been increasing, mainly due to the availability of a large supply and competitive pricing. Based on industry estimates, about 85% of soybean oil production is used domestically, with the remaining 15% being exported.

High oleic soybean oil

The US soybean industry is in full swing to expand the development and production of high oleic soybean to recapture lost market share in the food sector, and to venture into new market segments.

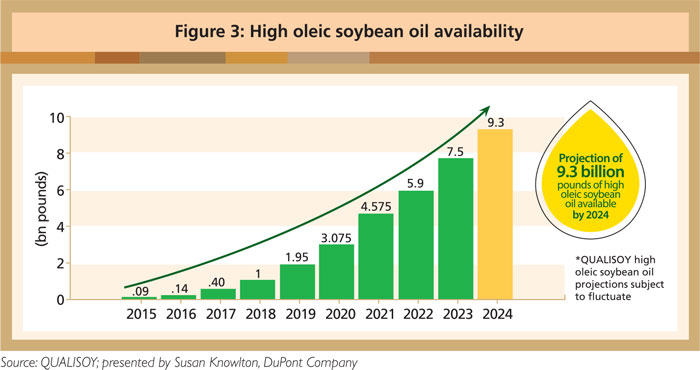

The American Soybean Association describes high oleic soybean as a GMO crop that delivers oil with lower saturated fat than conventional soybean oil and contributes no trans fats to products. It offers an extended product shelf life and features an improved fat profile. The high oleic soybean initiative was launched commercially in 2012. To accelerate productivity, the United Soybean Board (USB) has set a target of 18 million acres of high oleic soybean to be grown by 2023. On average, American soybean farmers grow approximately 80 million acres of soybean annually.

The US Food and Drug Administration’s decision to impose a trans fats labelling requirement in 2006 had a huge negative impact on the demand for hydrogenated soybean oil. A December 2019 article published by the USB stated that, to comply with the labelling requirement, US food manufacturers started using high oleic canola oil and palm oil as a replacement for partially hydrogenated soybean oil in baking and frying fats. This led to a doubling of imports of palm oil between 2005 and 2012.

The mandatory trans fats labelling law triggered a change in the edible oils market. The soybean industry started looking at ways of addressing critical losses in market share. This pushed the industry to invest heavily in research and development into soybean varieties that provide functional and nutritional benefits.

The USB indicated that the current momentum in the production of high oleic soybean oil is progressing as planned. According to a market projection by QUALISOY, an independent, third-party collaboration that promotes the development of soybean traits, about 9.3 billion pounds of high oleic soybean oil will be available by 2024 (Figure 3).

Palm oil market prospects

Despite its large domestic output, the US has remained a net importer of oils and fats for decades; in 2021, imports amounted to 5.2 million tonnes. The US is the largest importer of palm oil in the Americas region. According to the earliest recorded data published by the research group IndexMundi, palm oil has been available in the US since 1965. Palm oil imports have increased steadily over the years, recording a huge leap in volume between 2002 and 2008.

Over the last decade, consumption of edible oils and fats, including palm oil, has undergone considerable change in the US. Factors such as consumer awareness of oils and fats nutrition and health attributes, dietary guidelines, and legislation in the form of nutrition labelling of saturated and trans fats have helped shape the demand and consumption patterns.

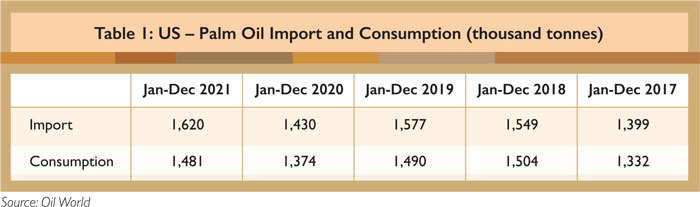

In 2021, US palm oil consumption amounted to 1.5 million tonnes (Table 1), or about 6% of total oils and fats consumption. Imports constituted about 32% of total oils and fats. Recent data published by Research and Market showed that, in 2021, the palm oil market in the US is valued at about US$11.9 billion.

The analysis by Research and Market also projected that future growth in the palm oil market will be driven by demand for certified sustainable palm oil, against a backdrop of concern over wildlife conservation, environmental and deforestation issues.

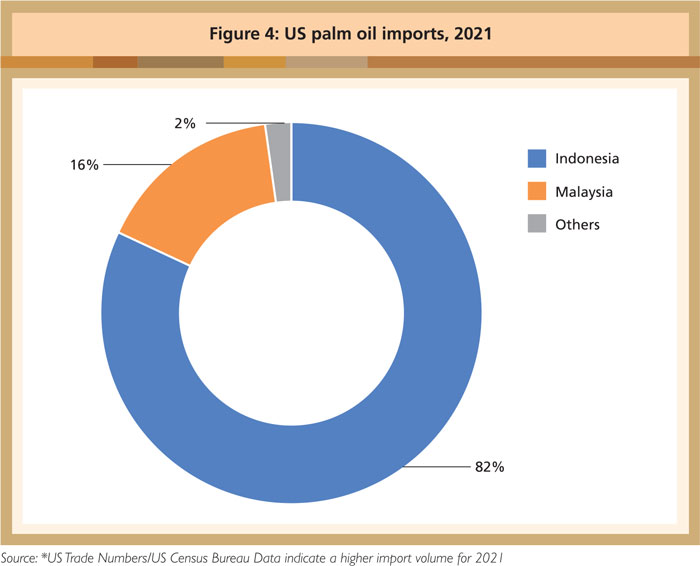

For many years, Indonesia and Malaysia have been the main suppliers of palm oil to the US – despite availability from South and Central America – mainly due to price competitiveness, product quality and sustainability.

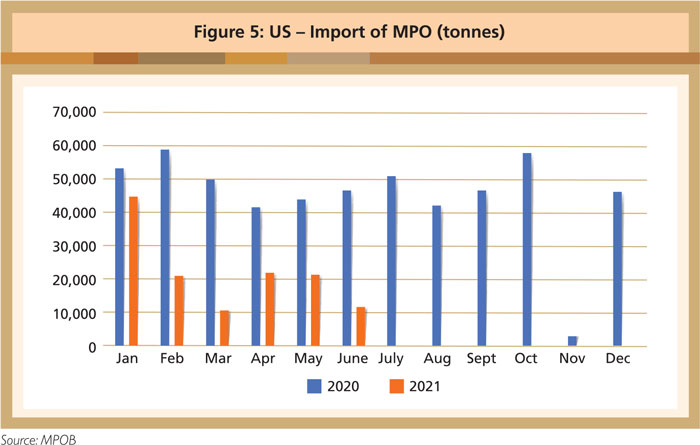

Malaysia dominated the US palm oil market for many years before Indonesia emerged as the front runner. Malaysian Palm Oil (MPO) imports by the US have been affected by the decision of the US Customs and Border Protection to issue a Withhold Release Order at the end of 2020 against two major palm oil producers and exporters, over the alleged use of forced labour. Despite the setbacks, the US remains the biggest destination for MPO in the Americas region, making up about 80% of the regional import volume or 334,663 tonnes in 2021.

According to a WorldCity analysis of the latest data published by the US Census Bureau, the value of palm oil imports rose 79.6% from US$635.78 million to US$1.14 billion for the first six months of 2022 compared to the first half of 2021. The five leading suppliers were Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Mexico and Colombia. The leading gateways were the Port of New Orleans, Louisiana (45%); Port of Savanna, Georgia (26%); Port of Stockton, California (9.4%); Port of Newark, New Jersey (5.3%); and Port of Richmond, California (4.2%).

US Census Bureau data revealed that in 1H 2022, palm oil imports amounted to 805,000 tonnes. Indonesia supplied 88% of the volume or about 708,400 tonnes, while Malaysia’s market share was 9.6% or 77,280 tonnes. Demand is projected to remain good, supported by strong purchasing power and a growing population. Two other key factors will also contribute to this.

Firstly, demand growth is foreseen for palm shortening in the Asian catering and restaurant businesses due to higher consumer interest. The industry includes both quick-service and full-service restaurants, bakeries and pastry shops. Interest in such cuisines is also being propelled by growth in the Asian American population. This is one of the fastest-growing groups in the US – a report published by the Pew Research Centre in 2017 put the figure at about 20 million, an increase of 72% since 2000.

The second contributing factor is related to the growing use of vegetable oils, such as palm oil, in non-food uses; this is expected to stimulate demand for palm oleochemicals. The focus will be on beauty and personal care products. Growing consumer demand for, and awareness of, sustainable and biodegradable products may improve the market for palm products in the cosmetics industry. A market report published by Grand View Research cited a shift in demographics of the young US consumer market, which spends a considerable amount of money on skincare and other personal care items.

MPOC Washington DC

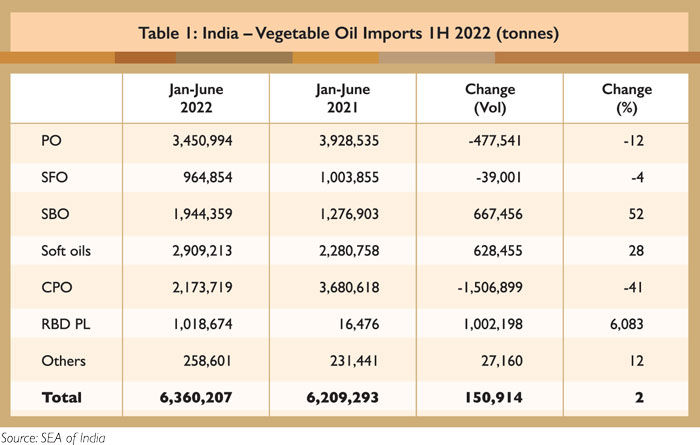

Indian vegetable oil demand remained intact over the first half of 2022, with imports rising by 2% year-on-year (y-o-y). High landed prices of palm oil and narrow spreads with soft oils led to a shift in demand towards soft oils. This reduced the palm oil share of vegetable oil imports to 54% against 63% y-o-y, while imports in 1H 2022 declined by 12% compared to the same period in 2021.

With supply disruptions in the countries of origin, the market share of major exporters also fell in 1H 2022. The Indonesian palm oil share dropped to 32% from 44% in 1H 2021. The Russia-Ukraine war led to a 4% y-o-y decline in sunflower oil imports largely from Ukraine, as importers switched to supplies from Russia and Argentina; about 80% of India’s annual imports have traditionally been from Ukraine.

A recent price drop discounted palm oil to soft oils by US$250-500/tonne, while increasing palm oil import parity to more than US$100/tonne. This will raise the palm oil import share.

India’s vegetable oil imports for 1H 2022 increased to 6.4 million tonnes (by 2%), against 6.2 million tonnes in 1H 2021. Imports during the first quarter of 2022 were higher by 16% over the comparative period, but the volume fell by 10% during the second quarter due to high prices attributed to the Russia-Ukraine war and other global factors.

Import disparity and narrow spreads with competing oils reduced palm oil demand in 1H 2022, as imports fell by 477,541 tonnes (12%) to 3.5 million tonnes (Table 1). In terms of volume, however, it remained the most traded commodity. The import of soft oils went up by 628,455 tonnes (28%) to 2.9 million tonnes, driven by higher soybean oil imports. The share of soft oils in the import basket stood at 46%, compared to 37% in 1H 2021.

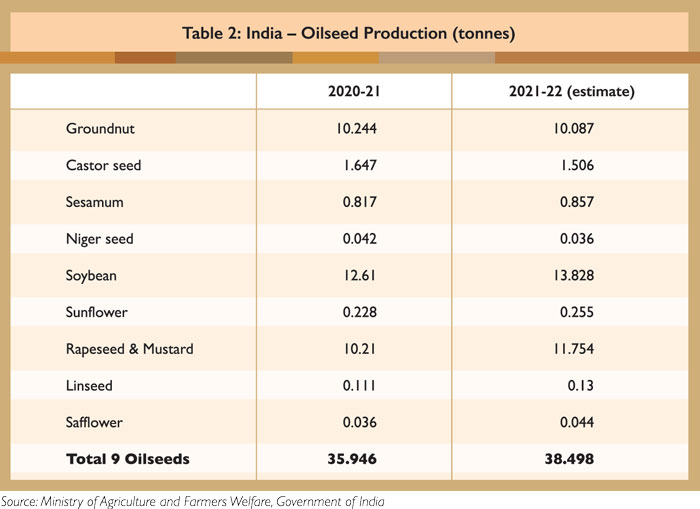

Domestic oilseed production in 2021-22 is pegged to rise by 7% to 38.5 million tonnes against 35.9 million tonnes in 2020-21. This is due to good price realisation for the output, encouraging farmers to plant more oilseeds in preference to competing crops. Total vegetable oil production in 2021-22 is estimated to rise by 5% to 10.3 million tonnes against 9.8 million tonnes in the previous year.

Import duties

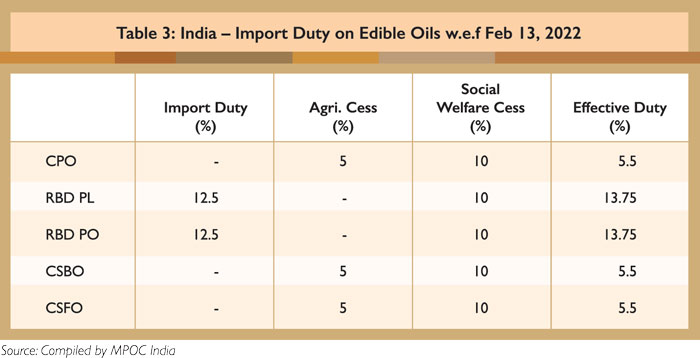

India had levied high import duty on edible oil imports in order to protect domestic oilseed producers. However, the Covid-19 pandemic caused global supply chain disruptions, while other macro-economic factors contributed to hiking up vegetable oil prices to exorbitant levels. This forced the government to reduce the import duty.

As a case in point, the import duty on CPO was as high as 44% in 2019. By the end of 2021, the effective import duty on CPO had come down to 8.25%, and on other crude oils to 13.75%. In 1H 2022, the import duty on CPO was further reduced, although there was no change for the other vegetable oils.

In order to support domestic processors and to control cooking oil prices, the government reduced the agri-cess on CPO to 5% with effect from Feb 13, 2022, bringing the effective import duty down to 5.5% from 8.25% (Table 3).

To control rising inflation, the government has allowed duty-free imports of crude soybean oil and crude sunflower oil – capped at 2 million tonnes for each – for the next two financial years with effect from May 25, 2022; this will facilitate the import of soybean oil at a lower price.

The Directorate-General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) was directed to allocate the tariff rate quota (TRQ) based on the refining capacity of applicants, as well as sales over the last three financial years. The objective is to extend the facility to actual processors of vegetable oil, not to traders.

The DGFT and Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution recently released the allotment under the TRQ, with a cap of 200 KMT per refiner. However, the Solvent Extractors Association of India has since requested a review, citing anomalies which would prevent the TRQ benefits from being transferred to consumers.

Many leading soybean and sunflower oil refiners who produce up to 1,000 KMT have been allocated only 200 KMT under the TRQ. This would compel them to import the quantity above 200 KMT at full duty. Smaller players, meanwhile, could take advantage of the higher duty-free import quota without passing on the full benefits to consumers.

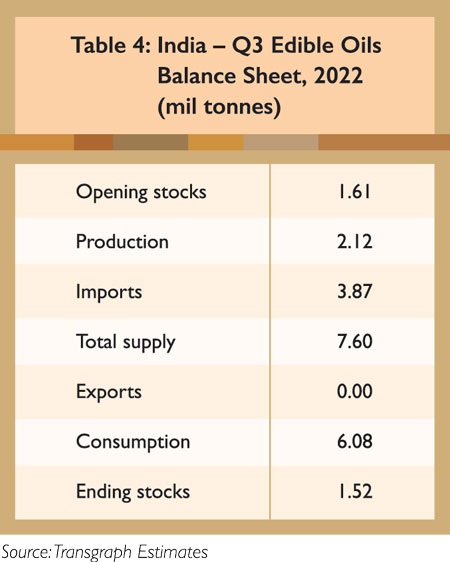

Domestic edible oil production in the third quarter of 2022 is projected at 2.1 million tonnes (Table 4), with imports estimated at 3.9 million tonnes (monthly average of about 1.3 million tonnes) in anticipation of escalated demand for festivals. Existing stocks stand at 1.6 million tonnes. Consumption is estimated at 6.1 million tonnes, compared to 5.7 million tonnes in the second quarter of the year.

MPOC India

On Nov 17, 2021, the European Commission (EC) published its draft proposal for a regulation on the import and export of commodities and products associated with deforestation and forest degradation (Draft Regulation), as well as a number of accompanying documents.

The rules are expected to cover six commodities – cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, soybean and wood. Annex 1 lists specific products – namely those that contain, have been fed with, or have been made using the commodities – to which the regulation will also apply.

The Draft Regulation will prohibit the import of the six commodities and their export from the EU market ‘unless they are deforestation-free and have been produced in accordance with the relevant legislation of the country of production’.

On June 28, 2022, the Council of the EU adopted its position regarding the Draft Regulation. The European Parliament’s Committee on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI Committee) had presented a Draft Report on April 20, introducing Compromise Amendments to the Draft Regulation. On July 12, the ENVI Committee adopted the Draft Report with 60 votes in favour, 2 against and 13 abstentions.

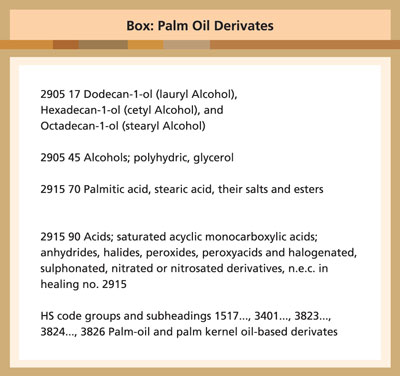

The Compromise Amendments will expand the scope of commodities covered by the Draft Regulation, adding swine, sheep and goats; poultry; palm-oil based derivates (see Box); maize; rubber; and other products, including charcoal and printed paper products, to the list.

Significant proposals

The ENVI Committee’s Draft Report further proposes a change to the meaning of the concept of ‘deforestation’, with four new definitions: ‘ecosystem conversion’, ‘agricultural use’, ‘other wooded land’ and ‘natural ecosystem’. The intention is to ensure that the Draft Regulation will cover not only land classified as ‘forest’, but also other land and ecosystems that are not classified as ‘forest’.

Currently, the definition of ‘deforestation’ in the Draft Regulation states that it ‘means the conversion of forest to agricultural use, whether human-induced or not’. This definition has been criticised by various organisations for being vague and not covering other ecosystems.

Therefore, the ENVI Committee proposes to define ‘deforestation’ as the ‘conversion, whether human-induced or not, of forests or other wooded land to agricultural use or to plantation forest’ (emphasis added).

The definition of ‘other wooded land’ means ‘land not classified as forest, spanning more than 0.5 ha, with trees higher than 5 metres and a canopy cover of 5-10%, or trees able to reach these thresholds in situ, or with a combined cover of shrubs, bushes and trees above 10%, excluding land that is predominantly under agricultural or urban use’.

Such definitions are particularly relevant as the ENVI Committee also proposes to include the assessment of forest conversion as part of the criteria to classify countries in ‘low’, ‘standard’, or ‘high-risk’ categories. If adopted in the final text, the definitions will have an impact on the classification of countries, as one criterion will be the ‘rate of deforestation, forest degradation and forest conversion’.

With respect to due diligence and enforcement, the ENVI Committee’s Draft Report notes that ‘while no country or commodity will be banned, companies placing products on the EU market would be obliged to exercise due diligence to evaluate risks in their supply chain’.

Importantly, the due diligence requirements will be derived from the ‘country benchmarking system’. In other words, obligations for operators and authorities in EU member-states will vary depending on the classification given to each country.

Notably, operators from ‘low-risk’ countries will have less onerous due diligence obligations, compared to those in ‘high-risk’ countries. The latter would have to provide, inter alia, a risk assessment to establish whether the relevant commodities and products are non-compliant with the requirements of the proposed regulation.

Under the EC’s Draft Regulation, such due diligence obligations only relate to deforestation and forest degradation or the production of products in accordance with ‘relevant legislation of the country of production’.

However, the ENVI Committee’s Draft Report proposes to amend the definition of ‘non-compliant’ to include the notion that a product must be also produced in accordance with ‘relevant laws and standards, including the rights of indigenous people, tenure rights of local communities, and the right to free, prior and informed consent, and which were not covered by an accurate due diligence statement’.

For example, traders and operators would need to provide information that the production of palm oil and derived products does not cause deforestation and forest degradation, and that it also complies with laws and standards regarding indigenous peoples’ rights.

Unless operators are able to prove that these products come from deforestation-free areas when originating in countries labelled as ‘standard’ or ‘high-risk’, the products look poised to be banned from the EU market.

Implications for palm oil

The Draft Report proposes to include specific palm oil and palm kernel oil-based derivatives within the scope of the Draft Regulation. These include ‘palmitic acid, stearic acid, their salts and esters’, which are used in food production.

While this could provide some clarity on the palm oil products to be covered, it is worth noting that there is no similar amendment regarding soybean derivatives, for example. Once again, a different approach towards palm oil can be observed. This appears to be discretionary and discriminatory in nature.

It would be in Malaysia’s interests to call upon the EC to classify countries according to transparent, science-based and objective criteria, with datasets gathered and verified with respect to all the commodities covered by the Draft Regulation.

This process of classification must also recognise Malaysia’s efforts and commitments towards the environment and sustainable production of palm oil and of all other commodities, whether or not they fall within the scope of the Draft Regulation.

Additionally, it should be emphasised that under the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil certification scheme, mandatory rules already confirm product compliance with a number of social and environmental standards. These should be counter-checked with the social and environmental elements referenced in the Draft Regulation.

The European Parliament is scheduled to vote on its Draft Report in September 2022. When it is adopted by the plenary, it will become the European Parliament’s position for the inter-institutional ‘trilogue’ negotiations with the Council and the EC, scheduled to begin after the summer recess.

The three institutions must agree on the text of the Draft Regulation, which will then have to be approved by the European Parliament’s plenary and by the Council. The EC will publish the measure in the EU’s Official Journal for adoption and implementation.

MPOC Brussels

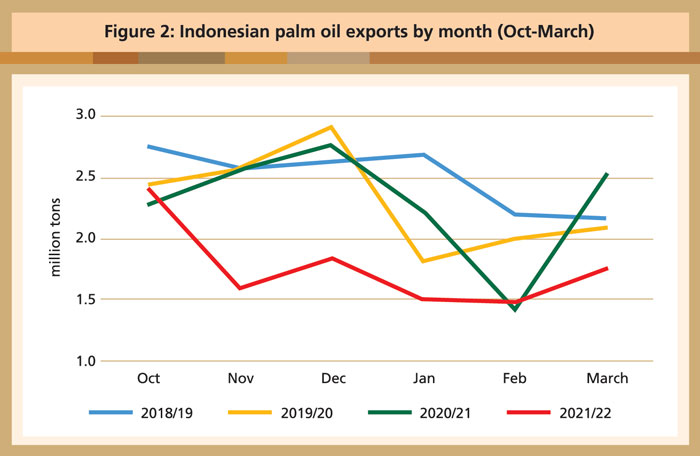

In marketing year 2021/22 (October to September), Indonesian palm oil exports were lower by 3 million tons [as at May 2022], down to a 12-year low of 25 million tons. The forecast is reduced on Indonesia’s slow export pace through the first six months of MY 2021/22 and various palm oil export policies in effect since November 2021. Although the government of Indonesia implemented a palm oil export ban on April 28, 2022, industry sources expect it to be short-lived and therefore have a limited impact on trade.

Cumulative shipments from October 2021 to March 2022 declined over 30% compared to the same period in MY 2020/21. Exports plunged after export taxes increased in November 2021. This reduced pace is expected to continue into May as Indonesia continues its restrictive export policies.

A stronger export pace is anticipated for the remainder of the marketing year. The current slow pace of exports is leading to a build-up of supplies that will need to be cleared from storage facilities to accommodate future production.

Market features

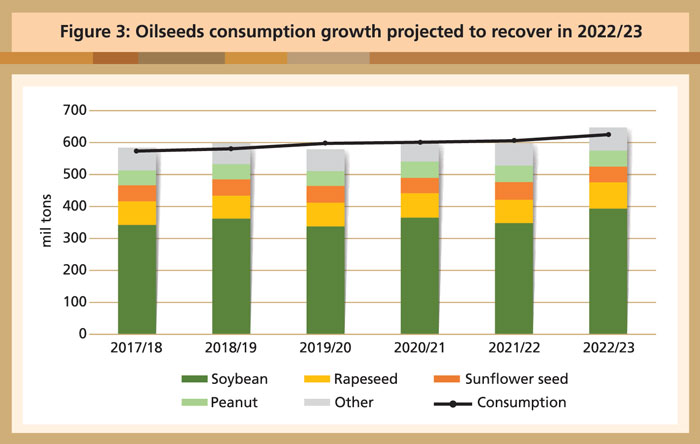

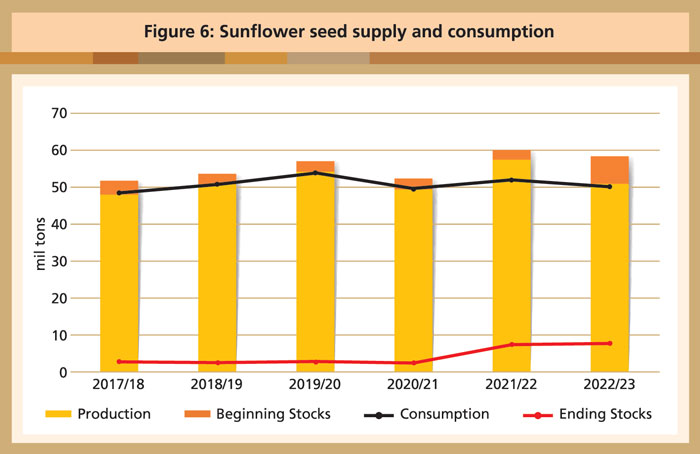

Global oilseed production is forecast to grow 8% in 2022/23, primarily on growth in soybean output in South America and the US, as well as rapeseed production in Canada and the European Union (EU), more than offsetting loses of sunflower seed output in Ukraine and Russia.

Global oilseed production is projected to reach 647 million tons, with soybean production forecast to rise 45 million tons to nearly 395 million, up 13%.

Global oilseed consumption is forecast to rise 3% in 2022/23, driven by higher China soybean demand as a result of a recovery from a decline seen in the last marketing year. Soybean crush and consumption are projected to account for most of the growth in global oilseed use. Sunflower seed consumption is projected down 3%, while rapeseed consumption is up 7%.

Global oilseed trade is forecast higher mostly on higher soybean demand from China. Trade in soybean, rapeseed, sunflower seed and peanuts is expected to rise, while cotton seed exports are forecast lower.

Global ending stocks are projected to rise on growing soybean production and stocks in South America and the US.

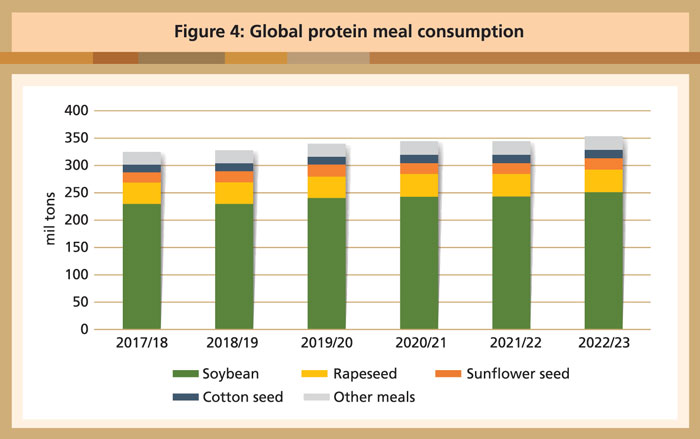

Global oilseed meal production is forecast to grow in 2022/23, led by soybean and rapeseed meal. Global consumption is expected to climb, mostly on robust demand from China. Trade in protein meal is expected to grow with higher soybean meal and rapeseed meal imports.

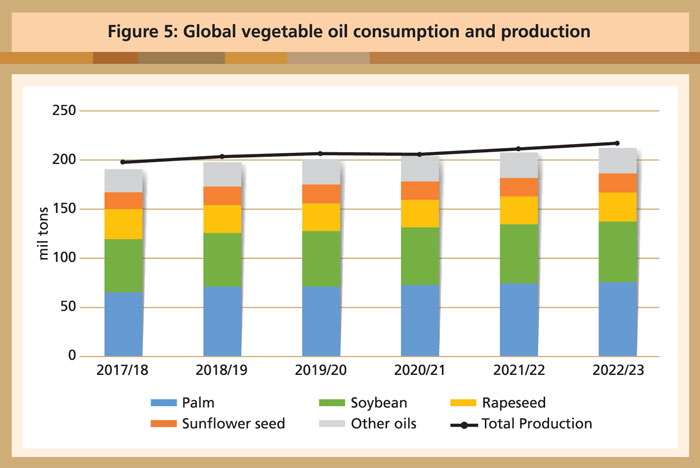

Global vegetable oil production is expected to grow by 3%, with major gains for soybean, rapeseed and palm oil, more than offsetting losses for sunflower seed and olive oil. Global consumption is forecast to expand by nearly 4.6 million tons (2%), primarily driven by palm and soybean oil growth in China.

Global vegetable oil trade will strengthen in 2022/23, owing to strong recovery in palm oil and rapeseed oil import growth. Global vegetable oil ending stocks are projected to grow by 4% to over 28 million tons.

2022/23 commodities outlook

Soybean

Global soybean production in 2022/23 is forecast at a record 394.7 million tons, up 13% from 2021/22. Likewise, soybean production in Brazil and the US is forecast at a record, continuing the trend of higher-concentrated production in exporting countries. If realised, year-over-year soybean production will expand by the largest amount in over a decade, predominantly on higher yields in South America following this year’s drought.

Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay account for more than 85% of production gains on both expanded planted area and higher yields. Soybean planted acres in Brazil are expected to grow for the 17th consecutive year, as high prices and a favourable exchange rate enhance producer returns despite high fertiliser prices. Plantings in the US are currently forecast to be a record as some farmers displace corn plantings due to high input costs.

Driven by expanding production, global soybean supplies will likely reach record levels. Export demand will continue to be led by China, which is projected to account for more than 50% of global trade growth while rebounding from this year’s slowing imports.

Export growth is forecast to outpace crush in the top three exporter countries in 2022/23 for the first time in three years on larger supplies and demand from China. Ample supplies are expected in exporter countries in 2022/23 and are responsible for the stronger growth in disappearance. Soybean stocks in the top three exporter countries on Sept 30, 2023 are expected to rise by 30% versus the previous year but remain well below the five-year average. China ending stocks are expected to grow much more modestly but remain at record levels.

Global soybean meal consumption is projected to rise 3% in 2022/23, a recovery from the slight downtick forecast for this year. China is expected to account for half of global consumption growth after a year of weaker soybean meal consumption. Exports are set to rise in line with consumption on a rebound in South America crush following improved soybean production prospects and higher US supplies.

Argentina’s share of global trade is projected to fall in 2022/23, while Paraguay, China and the US are forecast to see the largest growth in exports. Meal exports from Brazil and the US are forecast well above the five-year average as production gains are forecast to outpace domestic demand growth.

Soybean oil consumption is projected to rise 2%, mostly on the strength of China food use demand and higher US renewable diesel production. Global exports are forecast to rise 4% in 2022/23 with total global volume projected at a record 12.7 million tons.

Export growth is likely to be driven by South America on production gains outpacing domestic consumption growth and reduced competition from the US due to high domestic industrial usage. Remaining export growth is likely to come from European countries to offset reduced sunflower seed oil trade in the region due to the conflict in Ukraine.

Highlights

US soybean exports are projected to rise 1.6 million tons to 59.9 million tons on larger supplies and expected reduced export competition from Brazil at the start of the US harvest.Soybean supplies in 2022/23 are up on both higher carry-in and a larger crop, driven primarily by increased plantings. Soybean crush is forecast to rise at a slower pace than the previous year. Soybean meal exports are forecast to be a record, but strong domestic demand for soybean oil for renewable biodiesel will tighten exportable supplies and boost prices.

Argentina soybean production is projected to rise to 51 million tons on better weather and increased plantings. Trade is expected to recover from the current year with exports, mostly to China, at 4.7 million tons and imports, primarily from Paraguay, at 4.8 million. Strong demand for products and larger supplies will boost crush; however, increased competition from Paraguay, Brazil and the US will dampen meal and oil export growth. Soybean meal exports are forecast to rebound to 28.5 million tons, and soybean oil is projected to rise to 5.9 million tons.

Brazil soybean production is forecast to rise 24 million tons to 149 million tons on expected higher yields due to more favourable weather coupled with expanded planting in 2022/23.This will be the 17th straight year of expanded soybean plantings driven by strong export demand and excellent grower returns. Exports are projected to rise to 88.5 million tons, 5.8 million tons above the 2021/22 forecast. Crush is forecast to rise 1.3 million tons driven by strong crush margins and growing domestic meal and oil demand, leaving exports of soybean meal marginally higher and oil flat.

Rapeseed

Global rapeseed supplies in 2022/23 are projected to rise 10% to a record 100.5 million tons as production in Canada recovers from last year’s devastating drought. Both global harvested area and production are projected to be records. Reduced carryover, the smallest in nearly 20 years, will necessitate some stock-building in the coming year and provide a measure of price support.

Exports are projected to rise significantly above this year’s current forecast but will fall short of the 2020/21 record volume as stock building and strong crush recovery in Canada restrict exportable supplies. Global rapeseed crush is forecast to reach a record 75.1 million tons.

Global rapeseed meal production is forecast up 7% to a record in 2022/23. Canada leads the way in production growth as seed supplies rebound. Larger seed supplies in the EU and China, driven by larger production and seed imports, will facilitate crush and meal production growth in the coming year. Global rapeseed meal trade is projected to rise nearly 1 million tons as importers push purchases to near 2020/21 levels. Much of this is driven by increased exports from Canada. Higher meal production and increased trade will support record global consumption.