Palm Oil and the Circular Economy

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Techonology No Comments

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Techonology No Comments

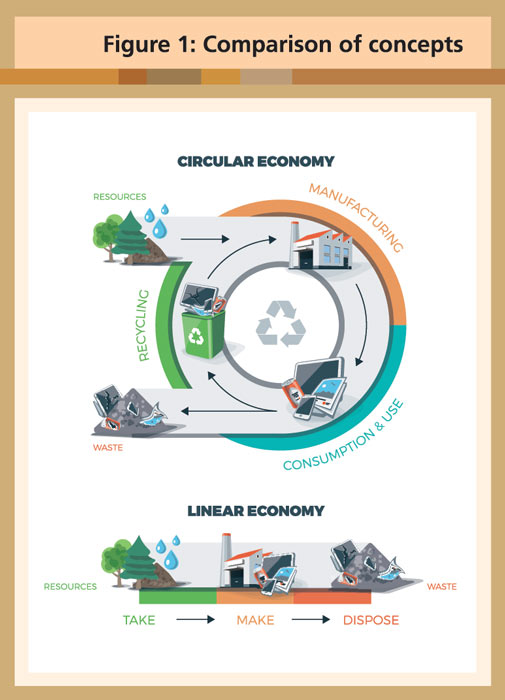

The circular economy (CE) – as opposed to a linear one – describes a regenerative system in which resource use and waste production, emissions and energy waste are minimised by slowing, reducing and closing the energy and material cycles.

This can be achieved through durable design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing and recycling. In practice, recycling – i.e. bringing waste products back into the cycle as secondary raw materials – plays the key role in the CE. This is of particular importance to the palm oil industry.

The linear economy, also known as the ‘throwaway economy’, is the current dominant principle of industrial production. A large part of the raw materials used is deposited or burned according to the life cycle of the products. Only a small proportion is reused.

Expressed as a simple formula, the antagonism between the two concepts is described as take-make-dispose (linear model) vs reduce-reuse-recycle (circular model).

Source: © petovarga/fotolia.com

However, it emerges that there are different schools of thought on the CE. They go by names like cradle-to-cradle, performance economy, biomimicry, industrial ecology or natural capitalism. What all of them have in common, though, is that they aim to:

The CE concept has gained traction in recent years with policy makers and business operators alike. While some researchers caution that it may be just another passing fad, there is no mistaking that the underlying assumptions are here to stay.

The assumptions have been around since the beginning of human economic activity. For instance, traditional agriculture has always been circular. The production energy in the form of human or animal muscle power was fed directly from the cultivated area. Waste like excretions or kitchen litter, and production residues such as straw or ashes from clearing land with fire, were returned directly to production.

Business entities and governments are therefore well advised to take a closer look at the CE. Some countries have already done so. China has had a CE Promotion Law since 2009. The indicator system used to measure its CE is an altered version of the EU´s material flow analysis, which the Chinese have studied extensively and adapted to their own needs.

The European Commission (EC), in its efforts to make Europe’s economy more sustainable, adopted a new set of measures in January 2018, called the CE package. It includes actions on plastics, waste legislation, critical raw materials and a monitoring framework. The EC’s work on the CE is influenced by the International Resource Panel established in 2007 by the United Nations Environment Programme.

In October 2018, the EC’s Directorate General for the Environment organised a CE Mission to Indonesia. This was to ‘build bridges between European institutions, NGOs and companies, as well as the relevant stakeholders in Indonesia interested in the opportunities that the transition to the circular economy brings’. With that, the CE reached the world’s biggest producer of palm oil.

There is not only an environmental case to be made for the CE, but an economic one as well. As British weekly The Economist writes: ‘Environmental problems, such as biodiversity loss, water, air, and soil pollution, resource depletion and excessive land use are increasingly jeopardising the earth’s life-support systems.’

The Economist also observes that more governments have come to realise that investing in sustainability and the CE, in fact, saves money. Take the example of public health: avoiding respiratory diseases by taking measures to improve air quality in cities may turn out cheaper than treating those affected.

The same is true at the corporate level. An increasing number of companies, investment funds and banks, especially in Europe, now accepts that the CE is not a costly fad or simply a way to satisfy the green lobby. Rather, it will improve the bottom line in the long run.

Optimism for palm oil in the CE

The production of palm oil results in enormous quantities of secondary products – palm oil mill effluent (POME), empty fruit bunches (EFB), palm oil mill sludge, oil palm fronds, oil palm trunks, decanter cake, seed shells and palm pressed fibres. The biomass has massive economic potential:

However, to make a financially feasible shift towards the CE is tricky. A vicious cycle must be overcome. Recycled materials must compete with virgin ones. A successful recycling industry must operate on scale. This would encourage investments in technology and efficiency to make recycling more competitive, and to provide a supply steady enough to create demand.

In a look at why businesses are trying to reduce, reuse and recycle, The Economist points out: ‘Things such as glass, paper and many metals have broken out of this vicious circle, typically once economies spewed out enough of them to make it worthwhile to recycle. Reprocessing technology had often been around for a while – paper was being recycled in the 19th century – but greater availability of source materials encouraged efficiencies. That in turn spurred demand for these materials and itself encouraged further improvements in recovery. In other words, a vicious cycle turned virtuous.’

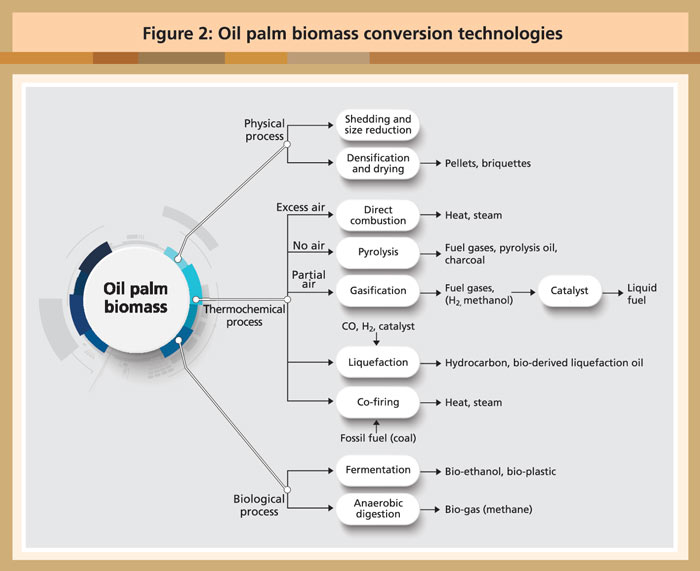

Given the abundance of recyclable biomass in the palm oil industry, plus the competitiveness of the resulting products, there is ample reason to be optimistic about the potential of the CE approach. There are many different use scenarios on the plantation and at the mill (Figure 2).

Source: Shuit, SH et al.; Oil palm biomass as a sustainable energy source: A Malaysian case study, in Energy 34(2009)

The expansion of palm oil production partly caused the tightening of environmental legislation screws in Europe. The next few years will show if this proves to be a happy coincidence for the palm oil industry after all.

Europe is decarbonising its economy. This means phasing out not only fossil fuels in the long run, but also moving away from first-generation biofuels. Electrical power will not be able to fill the gap, given the scarcity of the natural resources needed to build batteries and the environmental havoc caused by mining them.

Enter second-generation biofuels. European broker Greenea´s vision for the immediate future of biofuels is this:

Malaysia is in the midst of coming on board. Reports indicate that the Malaysian biogas market aims to equip all 447 palm oil mills in the country with biogas plants by 2020. That would be a momentous step forward. And who knows what other opportunities technological innovation might bring?

Just to give an example, the Malaysian Palm Oil Board has been experimenting with microwaves to sterilise fresh fruit bunches instead of using steam. On the one hand, this would eliminate POME (and the chance to capture methane); on the other, it would reduce the water content in empty fruit bunches, thus improving their suitability for use as fuel.

Prospects for palm oil in the energy sector seem promising. Rating agency Fitch has noted that incentives for advanced biofuels under the 2021-30 phase of the EU Renewable Energy Directive would boost demand for recycled palm oil and palm oil waste products, including mill effluent and EFB.

Other opportunities like the collection of used cooking oil (UCO) have not reached the mainstream of the palm oil industry. The European Union already imports UCO at scale. For the first eight months of 2018 alone, industry analyst Argus Media reports imports of more than 235,000 tonnes, four times the 2017 total. Similar developments are observable for biodiesel made from UCO.

Against this backdrop, the time has come for the Malaysian palm oil industry to think harder about the products it could sell. Investment in efficient processes will pay off not only in the production of palm oil, but also in processing the associated biomass.

MPOC Brussels

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Techonology No Comments

Each year, mobile phone brands hold launch events to unveil the latest version of their products and related features. These flashy events are designed to entice users into replacing their devices prematurely. Globally, on average, smartphone owners upgrade their devices within two years. Today, 69% of the world’s population uses smartphones and annual spending on new hardware exceeds US$370 billion.

We are increasingly being propelled into a digital world where new technologies are adopted almost as quickly as these hit the market. However, this situation accelerates the take-make-dispose cycle of the linear economy that has been dominant since the existence of the Industrial Age.

In the linear economy, raw materials are used to make products and discarded as waste after use, without much regard for Nature or the depleting supply of natural raw materials. For example, a company producing light bulbs takes raw materials such as glass or metal to manufacture its products. Light bulbs are sold to customers, who use it until these burn out. After that, the bulbs are disposed as waste.

In order to be profitable, such companies need to produce goods at the lowest cost possible or sell large quantities of the goods. The linear economy does not take into consideration the limited amount of resources available or the output of waste products through creation and use of the goods.

In contrast, the circular economy treats resources as if these are finite, and focuses on building sustainable economic health. The inherent restorative and regenerative design of the circular economy minimises or even eliminates waste, shifting towards the cradle-to-cradle production cycles. This means that product lifetimes are extended by offering options for used items to be returned and component parts repurposed into new products.

Beyond addressing the negative impacts of the linear economic models, the circular economy represents a shift towards a sustainable, resilient business and economic landscape that benefits the environment and society in its entirety. In reference to light bulbs, Phillips now offers the opportunity for companies to lease, rather than acquire, light bulbs over a longer period of time. This creates an incentive for Phillips to produce energy efficient lights, while companies save money on fixed office lighting costs and maintenance.

Traditional companies are attempting to move towards the circular economy. H&M, one of the world’s largest clothing retailers, is working on a strategy to become 100% circular by collecting old clothing in stores for recycling. Since 2013, H&M reports to have gathered more than 55,000 tonnes of fabric.

Disruptive technologies also support the transition to a circular economy by radically increasing virtualisation, de-materialisation, transparency and feedback-driven intelligence. In addition, the shift to a circular economy requires innovative business models that either replace existing ones or seize new opportunities.

The increasing popularity of access-over-ownership business models has been accelerated by the capabilities offered by disruptive technologies. A new generation of consumers places less emphasis on owning and more on sharing, bartering and renting goods. This shift in consumer behaviour, coupled with the capabilities of emerging technologies, has propelled an entirely new range of businesses – from shared car rides offered by companies like BlaBlaCar, to sharing accommodation on holiday via the likes of Airbnb.

Advancements in 3D printing technology are similarly paving the way for innovative manufacturing and production approaches. This enables the circular economy by disrupting the existing materials value chain and increasing the efficiency of the production process.

With the gradual reduction in price and improvements in quality, 3D printers could become commonplace in each home, similar to other household electronics. The option to acquire designs online and print our own products, from clothing to electronic parts and even food, could become routine. This sort of on-demand, hyper-personalised production could mean significant reductions in waste and increased efficiencies.

Governments and regulators are actively trying to support the circular economy. The European Parliament recently backed several laws that support the shift in EU policy towards a circular economy. According to the laws, by 2025, at least 55% of municipal waste should be recycled and 65% of packaging material will have to be recycled. In addition, the European Parliament has overwhelmingly backed a wide-ranging ban on single-use plastics. The benefits of a circular economy to the environment, climate and human health are widely recognised and accepted.

However, a majority of the regulatory environment, as well as economic incentives, still favour linear business practices. The current inability of supply chain stakeholders to track the provenance of materials, components and products throughout the value chain prevents assertion of their circularity – from extraction or creation, all the way through the many life cycle stages. In this respect, application of blockchain technology will have a transformative impact and enable a circular economy.

Essentially a distributed digital ledger system, blockchain was originally developed to record transactions for bitcoin, a well-known digital currency. Although digital currencies face scepticism and volatility in the global market, the underlying blockchain technology has grown in terms of credibility as more potential applications are developed across various industries.

Uses of blockchain technology

Supply chain management has emerged as one of the major use cases for blockchain technology, offering an efficient and almost fully tamper-proof way of tracking the cradle-to-cradle life cycle of goods. The blockchain translates chain of custody across the value chain into a distributed, immutable, digital trail that asserts the circularity of products.

For example, Bext360 combines several disruptive technologies, such as the Internet of Things, blockchain and artificial intelligence (AI), to create a fair and transparent coffee supply chain:

Since the Industrial Age, supply chains have followed a competitive business model that limits opportunities to create and leverage synergies. In addition, intermediaries continue to benefit from the lack of trust between supply chain stakeholders who are reluctant to share information and compete on costs.

In order to enable and engage in a circular economy, stakeholders need to be able to collect, process and share data within a trustworthy and secure environment. Blockchain technology, in combination with AI systems and the Internet of Things, could help establish a trust economy that lowers collusion between centralised parties, while also making them accountable.

Blockchain technology enables stakeholders to gather more knowledge on material cycles and processes throughout the value chain and to share data securely.

For instance, the startup Provenance intends to design a blockchain system that is able to track all used materials, including the dimensions of quality, quantity and ownership, over the whole supply chain in real-time. Basically, Provenance is trying to achieve a digital passport for any product, which enables consumers and producers to track the whole production process.

Foundation for success

Based on the current development trajectory of blockchain technology, it would be possible to establish a macro-economic incentive system that promotes transformation to a circular economy.

Within the linear economic system, raw materials are extracted from Nature, transformed into products and, finally, disposed back to Nature. Although the linear model could incorporate recycling, most of the components within this system have not been designed for reuse or regeneration, resulting in significant material degradation and accumulation of waste in the environment.

For example, the world today generates around 40 million tonnes of electronic waste each year. Even when recycled, a significant amount of electronic materials cannot be recovered. Conversely, the circular model aims to achieve a waste-free system – an economy which functions in loops and maintains the ecological value of materials over time.

With the application of blockchain technology, it will become possible to unambiguously identify a product’s inputs, including the quantity, quality and origin of materials. In addition, information regarding a product’s biological or technical components could be tracked on a blockchain. A blockchain-based system which is able to track product attributes would make it possible to adjust taxes according to the level of material degradation.

Ultimately, the application of blockchain technology could potentially enable transparency and traceability across end-to-end value chains, as well as crate a macro-economic incentive system that promotes the transformation to a circular economy.

Kamales Lardi

Digital Transformation Strategist

Lardi & Partner Consulting GmbH, Switzerland

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Techonology No Comments

The future of the palm oil industry has become uncertain in Europe. Last year, the European Parliament came close to a ban on palm oil imports in the region. The vote in favour of the revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) proposed to remove biofuels made from palm oil from the list of biofuels that counts towards the EU’s renewables target for 2021. The ramifications would have been significant, not only for palm methyl ester imports, but also for future hydro-treated vegetable oil (which uses palm oil as feedstock).

I have attended several biofuels conferences where the RED II and its potential impact on the industry were discussed in depth. As an objective external observer, I’ve found that the discussions tended to be emotionally charged, and based on perceived environmental and human rights violations by the industry.

Today, the dissemination of inaccurate information or ‘fake news’ is a challenge faced by many industries. Distorted information is able to directly shape public perception and even impact the direction of policy development across regions. As such, building an ecosystem of trust between palm oil producers, regulators, companies, environmentalists and end consumers will be pivotal in ensuring that the industry continues to thrive, particularly in the European market.

Social media and digital marketing channels have proven to be powerful and efficient tools for disseminating information and shaping public opinions. Over 50% of the European population actively uses social media channels. By launching strong promotions and campaigns focused on countering inaccurate information with facts on these channels, Malaysian palm oil could create a direct line of communication with the end consumer.

In addition, the application of blockchain technology could have a transformative impact on the palm oil industry by creating an auditable and traceable end-to-end supply chain. Imagine a customer in a store looking to buy a bottle of shampoo that has a ‘deforestation-free’ label on it. With a simple mobile app, the customer is able to see where the palm oil used in the shampoo originates, including a video that shows the plantation where the fresh fruit bunches and oil palm tree were grown, and how exactly the palm oil ended up in the shampoo production. These palm kernels have been tracked across the globe with blockchain technology.

Blockchain is essentially a distributed digital ledger system. It was originally developed to record transactions for bitcoin, a well-known digital currency. Although digital currencies face scepticism in the global market, the underlying blockchain technology has grown in terms of credibility as more potential applications across various industries are developed.

Supply chain management has emerged as a legitimate use case for blockchain technology, tracking raw materials through production and allowing everyone in the supply chain to know where a shipment is located.

So, what makes blockchain unique? The digital ledger records transactions in a series of blocks, and exists as multiple copies spread over multiple computers. The ledger is secure because each new block of transaction is linked back to the previous block in a way that makes tampering practically impossible.

Each time new data is added, all copies of the ledger are updated and validated simultaneously, while previous data records cannot be altered. This decentralised structure means that no single person or group has full control over the data.

Blockchain technology is applicable in any business or industry, to record transactions of almost anything of value. Emerging applications for blockchain technology are geared to improve business operations in numerous ways, including supply chain transparency and credibility for all kinds of products.

Last year, for example, shipping conglomerate Maersk deployed a blockchain-based electronic shipping system to digitise supply chains and track international cargo in real time. The advantage of blockchain technology is the immutable records of data and the trust people can have in it.

Infallible validation system

In the palm oil industry, the use of blockchain technology combined with mobile apps and other related technology, such as QR Codes, RFID tags and Internet-connected sensors, could result in near-perfect sustainability records.

Malaysia is currently working to certify the sustainability of its palm oil through a mandatory programme for the entire production and supply chain by Jan 1, 2020. The Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil standard is aimed at offsetting negative perceptions about the industry and `fake news’ that has been misleading consumers, particularly in Europe.

At its core, existing certification schemes still depend on some form of manual Chain of Custody systems. In other words, doubts about the validity of the certification schemes may be related to the dependency on human intervention and paper-based processes that may be subject to errors or malicious activities.

The application of blockchain technology in the Malaysian palm oil industry has the potential to alleviate any doubts, by creating greater transparency and auditability across the entire supply chain. Instead of having to trust the elements of a certification process where doubt may be cast due to paper-based or human error, blockchain technology offers an infallible validation system that secures trust.

This not only provides an unprecedented level of transparency, but also contributes to protecting the working conditions and legal employment of field workers, and gives plantations rich data on crop harvesting.

With the use of geolocation features, farmers, governments, certification authorities and producers can maintain digital inventories of the plantations, and implement sustainable land usage planning policy. Additionally, use of sensor technology could minimise spoilage by monitoring temperature and humidity during processing, storage and transport, and integrating this data on the blockchain.

The oil palm industry in Southeast Asia is a saving grace for many small farming families. In addition, growing oil palm requires less land and results in higher yield than other vegetable oil crops. In May 2018, a study by researchers at Imperial College London revealed some of the challenges faced by companies in guaranteeing products labelled as ‘deforestation-free’.

The lead author of the study, Joss Lyons-White of the Grantham Institute – Climate Change and the Environment and the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial said: ‘Deforestation-free palm oil is possible, but our study found it is very challenging for companies to guarantee at present.

‘For example, supply chains are so complex that tracing palm oil back to source is very difficult – lots of trade may occur between different parties before manufacturing, where the palm oil is used in many different products for different purposes. This makes it hard to know exactly where the original oil was from – and whether it was linked to deforestation or not. However, simply banning palm oil is unlikely to be the answer. Instead, we need to find ways to ensure commitments can be implemented more effectively.’

Establishing sustainable practices in the palm oil industry needs to strike a balance between several aspects – human rights, environmental impact and economic contributions. The application of blockchain technology could be a solution that would enable Malaysia to utilise the existing palm oil infrastructure and guarantee that sustainable practices are implemented and continuously tracked.

Kamales Lardi

Digital Transformation Strategist

Lardi & Partner Consulting GmbH

Switzerland