Solidaridad: Invest in Sustainability of Oil Palm Smallholdings

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, October 18th, 2022 in Sustainability No Comments

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, October 18th, 2022 in Sustainability No Comments

While oil palm smallholders risk living in poverty, the US$282 billion palm oil industry creates huge profits for companies. The pivotal role of smallholders, currently contributing to about 30% of global production, is often overlooked in the sustainability agenda, as policies tend to focus on large industrial plantations. And with their contribution to palm oil production expected to grow, smallholders play an increasingly central role in rural economic development and preserving biodiversity.

With palm oil as a crucial ingredient in the diet of the poorest people on earth, and its widespread presence in products like margarine, shampoo and biodiesel, it’s here to stay. Supply chain-wide smallholder inclusion is crucial for sustainable palm oil production.

The first global Palm Oil Barometer by Solidaridad and smallholder producer organisations in Asia, Africa and Latin-America, gives a new perspective on the largely negative public debate around palm oil in western countries. This crop presents more issues and more opportunities than many people realise.

Deforestation and poverty are interlinked

Palm oil production features prominently in the media as a cause of deforestation, biodiversity loss and climate change. However, by isolating its impact on the environment from the poverty crisis, to which it is directly linked, it is easy to overlook the vital role smallholders play in palm oil production.

Although the image of large companies growing vast expanses of oil palm as a monoculture holds true, more than three million smallholders and their families produce roughly 30% of the world’s palm oil. And a multitude of workers find jobs in oil palm cultivation. In Indonesia alone, there are around 16 million workers in the sector, the majority of whom are employed by smallholders. The contribution of smallholders in the overall supply of palm oil is only expected to increase, as industrial-scale companies are forced to limit expansion due to zero-deforestation commitments.

Shatadru Chattopadhayay, Managing Director of Solidaridad Asia, reflects: “Smallholders produce not even 2% of certified sustainable palm oil on the market, while contributing 30% of the world’s supply. Governments and businesses must make smallholder inclusion part of their sustainability criteria.”

Smallholders do not get their fair share

Smallholders generated US$17 billion of the palm oil industry’s US$282 billion turnover in 2020, yet many did not earn enough to cover their family’s essential living costs. Despite this, many smallholders prefer growing oil palm to other crops like rubber or coffee, because they earn a higher and more consistent income throughout the year. For many smallholders, growing oil palm gives them better prospects and alleviates poverty.

Multiple factors can influence a farm’s profitability, including its size, labour and fertiliser costs, market access and prices. Volatile market prices squeeze smallholder margins that are already narrow.

“It’s getting more and more difficult for farmers with all these changes in the prices. Some feel as if 50% of their livelihood has been lost as the prices of the fresh fruit bunches have been slashed and, at the same time, the price of fertilisers and pesticides have risen by more than 100%,” said Valens Andi, head of a farmers’ cooperative in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, to Al-Jazeera.

Faced with these precarious conditions, many smallholders are unable to invest in farm-level innovations or adhere to sustainability standards. By 2030, smallholdings will account for around 60% of Indonesia’s oil palm area. Supporting these smallholders to produce sustainably will be a key challenge in the coming years.

Fair value distribution is at the heart of sustainable palm oil production

At the other end of the chain, food manufacturers, consumer goods companies and retailers take 66% of the gross profits on palm oil in food, household and body care products. The focus on cost-cutting to optimise profits contrasts starkly with individual companies’ sustainability commitments, as well as the global climate and UN Sustainable Development Goal agendas.

The concern is that global palm oil buyers show little willingness to compensate small producers for operating sustainably, for example, by paying a fair price and investing in long-term trading relationships. A fairer value and risk distribution across the palm oil value chain enables farmers to both produce sustainably and make an income that sustains their family’s livelihood.

Stop boycotting and start investing in good palm oil production

Smallholder interests are not only overlooked in the value chain, but their role and interests are also ignored in the public debate. Campaigns by NGOs and commercial brands call for a palm oil boycott to combat biodiversity loss. Many academics and conservation organisations agree that banning palm oil would simply shift the problem elsewhere, threatening other habitats and species.

Oil palm is far more productive than any other vegetable oil crop. On average, it is five times more productive than soybean. Replacing oil palm with alternatives would intensify the battle for scarce farmland. Instead of boycotting palm oil, the industry should invest in sustainable production by smallholders.

Bring smallholder voices to the fore

Farmers’ organisations should play a key role in the debate on the future of palm oil. Focusing on fair value distribution and minimising environmental degradation is key. The private sector and governments need to move from technical assistance to programmes that address the structural disadvantages at smallholder level. Solutions will not be the same everywhere and have to be found in a combination of voluntary and mandatory approaches.

Heske Verburg, Managing Director of Solidaridad Europe, recommends: “Companies and governments in consuming and producing regions [should] include smallholders’ interests when developing and implementing policies. The EU should ensure that smallholders will be supported to meet the requirements of the EU Regulation on deforestation-free products and, in partnership with producing countries, tackle the root causes of deforestation, including poverty.”

Source: Solidaridad Network

By gofb-adm on Saturday, August 20th, 2022 in Issue 2 - 2022, Sustainability No Comments

Compared to its predecessor, the MS 2530:2022 standard was developed with a very different industry baseline knowledge on sustainable oil palm management practices. In 2013, sustainable certification of oil palm was only implemented by large industry players.

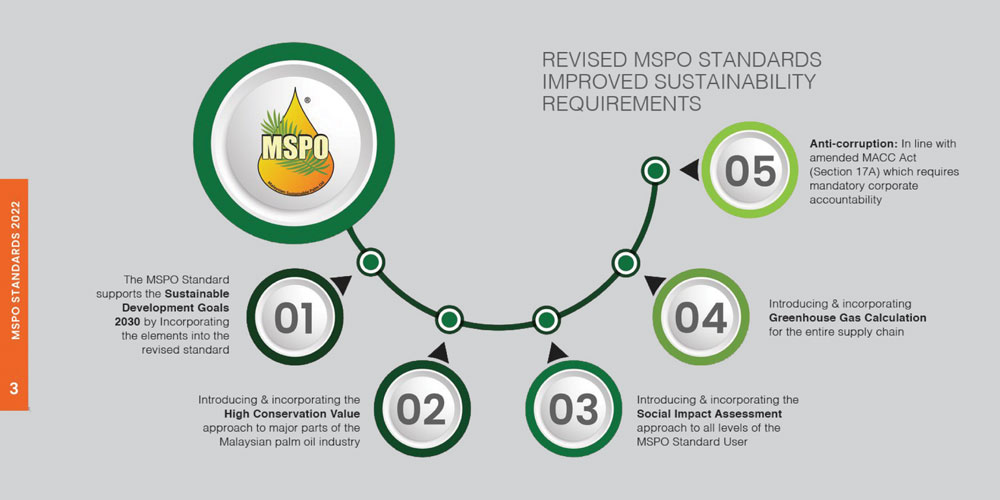

Based on groundwork established by the MS 2530:2013 standard, revised Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) standards were launched in March 2022 with more awareness about sustainable practices and the capacity to implement them, which was not previously present.

The MS 2530:2022 standard retains the four main parts, but is further divided into eight separate parts. This is to cater to differences in capacity and scale of the implementers of the MSPO.

Scope of the MS 2530:2022 standard

MS 2530-1:2022 – MSPO Part 1: General Principles

Part 1 lists the general principles of the standard. It provides the framework for the other parts and includes terms and definitions used throughout the standard. Part 1 does not contain requirements used to assess conformity.

MS 2530-2-1:2022 – MSPO Part 2-1: General Principles for Independent Smallholders (less than 40.46 ha)

Part 2-1 contains requirements used to assess conformity for independent smallholders against the MSPO. Independent smallholders are categorised as individual farmers who own or lease less than 40.46 ha (100 acres) of an oil palm smallholding and manage the smallholding themselves.

MS 2530-2-2:2022 – MSPO Part 2-2: General Principles for Organised Smallholders (less than 40.46 ha)

Part 2-2 contains requirements used to assess conformity for organised smallholders against the MSPO. This refers to individual farmers who own or lease less than 40.46 ha of an oil palm smallholding, and the holdings are managed by government agencies such as FELDA, RISDA, FELCRA, SALCRA and SLDB.

MS 2530-3-1:2022 – MSPO Part 3-1: General Principles for Oil Palm Plantations (40.46 ha to 500 ha)

Part 3-1 contains requirements used to assess conformity against the MSPO for small oil palm estates between 40.46 ha and 500 ha.

MS 2530-3-2:2022 – MSPO Part 3-2: General Principles for Oil Palm Plantations (more than 500 ha)

Part 3-2 contains requirements used to assess conformity against the MSPO for large oil palm estates/plantations with areas of more than 500 ha.

MS 2530-4-1:2022 – MSPO Part 4-1: General Principles for Palm Oil Mills including Supply Chain Requirements

Part 4-1 contains requirements used to assess conformity for palm oil mills against the MSPO. This standard contains requirements for sustainable management, as well as supply chain requirements.

MS 2530-4-2:2022 – MSPO Part 4-2: General Principles for Palm Oil Processing Facilities including Supply Chain Requirements

Part 4-2 contains requirements used to assess conformity for palm oil processing facilities – such as for crude palm oil and palm kernel – against the MSPO. This standard contains requirements for supply chain requirements, as well as introduces requirements for sustainable management practices.

MS 2530-4-3:2022 – MSPO Part 4-3: General Principles for Dealers including Supply Chain Requirements

Part 4-3 contains requirements used to assess conformity for fresh fruit bunch dealers and palm oil traders against the MSPO. The category includes all types of dealers under MPOB licensing, including exporters and importers that purchase and sell oil palm products without changing the chemical properties of the materials. This standard contains requirements for sustainable management, as well as supply chain requirements.

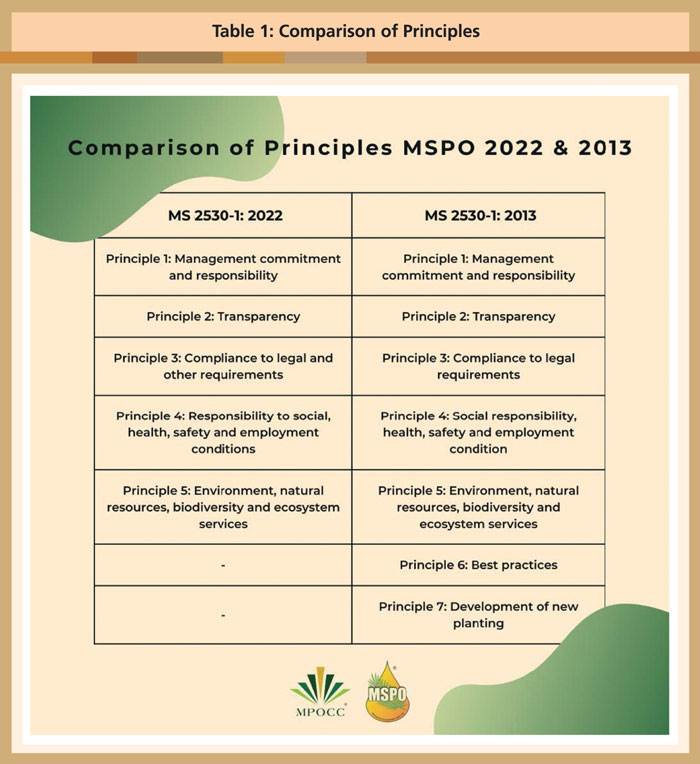

The new framework for MSPO Standards has only five principles compared to the previous version of seven principles (Table 1). This was decided by the Technical Committee on MSPO to further streamline the requirements to be consistent with the overall flow.

Principles 1-5 are very similar between the MS 2530:2013 and the MS 2530:2022 standards. Principle 6 of MSPO 2013 has been amalgamated into Principles 1, 2, 4 and 5. The requirements for new plantings have been strengthened and incorporated mainly into Principle 1, with supporting requirements appearing in Principle 4 and Principle 5.

Cheah Chi Ern

Systems Management Manager

Malaysian Palm Oil Certification Council

By gofb-adm on Saturday, August 20th, 2022 in Issue 2 - 2022, Sustainability No Comments

The MS 2530:2013 series of standards under the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) scheme has driven sustainability initiatives since implementation began in 2013. This has contributed to the transformation of the Malaysian industry in producing sustainable palm oil. The amount of human and financial investment in industry development has been massive, especially in ensuring continuous compliance by users of the standard. The impact has been extensive on both business standards and national policies on the commodity.

However, the Malaysian Palm Oil Certification Council (MPOCC) understands the need to further address market destination requirements, business and consumer needs, as well as the trajectory of certified sustainable palm oil. The MSPO 2022 version (MS 2530:2022 series of standards) – derived through a credible consultative process – will address all those concerns. The revisions have been based on international practices and are in accordance with the Standard Setting Process of the Department of Standards Malaysia (Standards Malaysia).

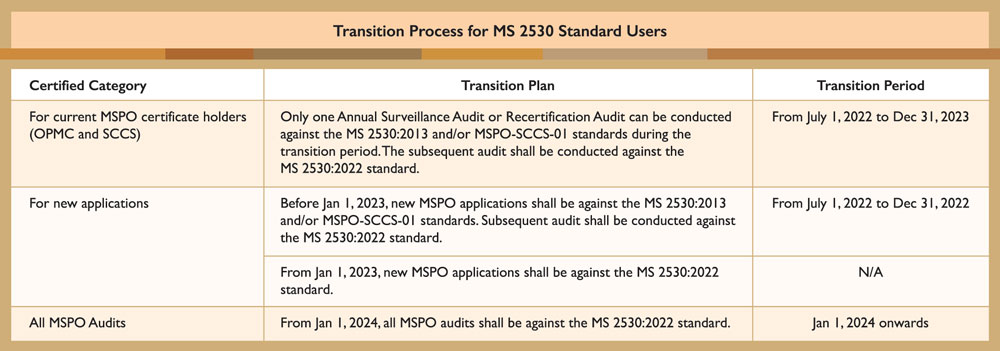

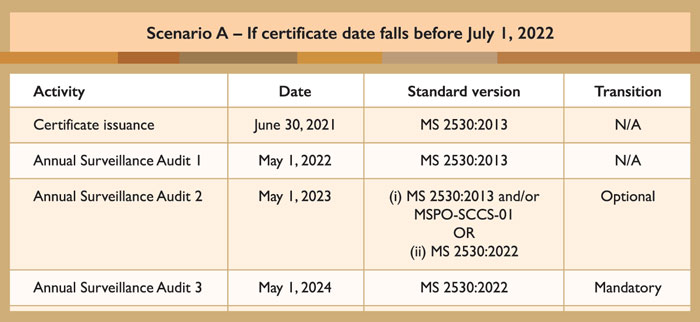

The MS 2530:2022 standard series were launched on March 22, 2022, following approval by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry on Jan 27, 2022. It will replace the MS 2530:2013 series and the Supply Chain Certification Standard (MSPO-SCCS-01).

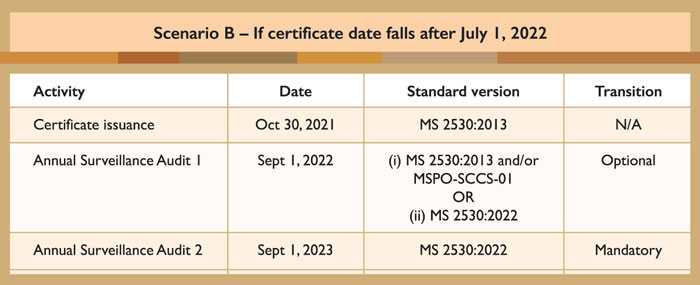

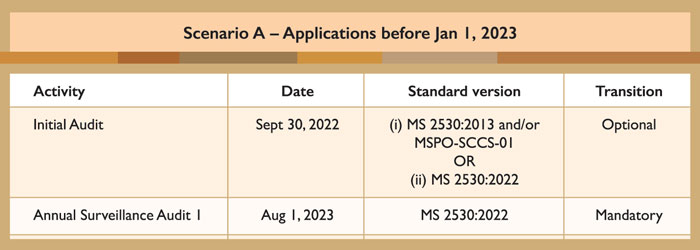

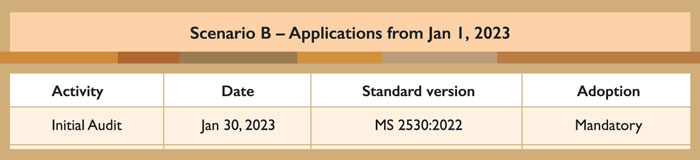

A systematic approach is now required to enable smooth implementation, taking into account new actors within the palm oil value chain, and additional needs in meeting environment, social and governance issues. For this, a feasible transition roadmap has been established. The English Language version will be applied over 18 months from July 1, 2022 to Dec 31, 2023. All audits from Jan 1, 2024 will be carried out against the MS 2530:2022 standard.

Accredited Certification Bodies

All accredited certification bodies (ACBs) are required to adhere to the following:

Note: Only CBs accredited to that particular scope can conduct audits for these parts.

Certificate holders and new applications

Current certificate holders

New Applications

Malaysian Palm Oil Certification Council

By gofb-adm on Sunday, May 1st, 2022 in Issue 1 - 2022, Sustainability No Comments

The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries (CPOPC) has developed and launched the Global Framework Principles of Sustainable Palm Oil (GFP-SPO), which aims to provide a common language across different certification schemes being applied to palm oil production. It is anchored in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as its base.

The framework can also be used to value the contribution of palm oil toward achieving sustainable development in all producing countries, and to lay the foundations for the establishment of sustainability of a vegetable oils platform. This important document was adopted and approved by Ministers of CPOPC member-countries at their 9th Ministerial Meeting on Dec 4, 2021.

The GFP-SPO was officially launched on Feb 16, 2022, via a webinar. In attendance were representatives of CPOPC member-countries and observer countries – Indonesia, Malaysia, Colombia, Thailand, Ghana, Honduras, the Philippines, Sierra Leone and Papua New Guinea – as well as stakeholders in palm oil sustainability schemes.

At the launch, CPOPC Executive Director Tan Sri Dr Yusof Basiron asserted that palm oil contributes to the SDGs: “CPOPC believes that palm oil is a sustainable alternative to other vegetable oils such as soybean, rapeseed and sunflower across all the three SDG focus areas – social, economic and environmental.

“Therefore, the GFP will be used as a reference because its principles will draw and expand upon the current sustainable palm oil certification schemes, such the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) and Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil, and provide guidance to future ones.”

Indonesia’s Deputy Minister for Food and Agribusiness, Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs, Dr Musdhalifah Machmud, emphasised: “In collaboration and support of the current certification schemes, the GFP-SPO can provide a common language across systems and benchmarks. It is worth noting that this framework is voluntary and is not intended to be a new palm oil certification scheme but rather, a critical reference applicable to existing and future schemes.”

Malaysian Ministry of Plantation Industries and Commodities Secretary-General Datuk Ravi Muthayah said: “The GFP-SPO is important in ensuring that palm oil is able to meet world demand in a sustainable and productive way by adhering to the SDG principles. The principles are global in nature and universally applicable, taking into account different national realities and levels of development.”

Platform for producers

Presenting an overview of the global demand of palm oil and the framework, Sustainability Consultant Ziv Ragowsky reaffirmed that the GFP-SPO is a platform of collaboration among the producers of vegetable oils.

The idea of having the framework is to have discussions between palm oil producing countries, other stakeholders and the UN; and to have a positive discourse that avoids difficulties and frictions in pitting one stakeholder against another, he said.

Team Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil Secretariat Coordinator Dr Herdradjat Natawidjaja connected the GFP-SPO and ISPO in covering the 7 Principles towards achieving the global SDGs.

The principles are compliance with regulations; implementation of good agricultural practices; management of the environment, natural resources and biodiversity; responsibility to workers; social responsibility and community economic empowerment; application of transparency; and sustainable business improvement.

Malaysian Palm Oil Certification Council representative, System Management Department Senior Manager Simon Selvaraj, shared that the framework would be useful in coordinating Indonesian and Malaysian sustainability efforts from the economic, environmental and social aspects.

The framework has elevated the bar in sustainability requirements because it is able to holistically measure the UN SDGs, he noted, adding that the GFP-SPO would play a wider role in addressing sustainability issues with early adoption. This will significantly help everyone in the supply chain.

CPOPC Deputy Executive Director Dupito Simamora concluded the webinar by affirming the continued efforts of palm oil producing countries to attain a sustainable supply chain, “Palm oil has led by examples to continuously improve the sustainability framework, which should be emulated by producers of other vegetable oils. International support would be required from other palm oil producing countries, relevant organisations, as well as UN bodies for the framework to be extrapolated to all oils,” he said.

Co-creating solutions

The second introductory webinar on March 4, 2022, was well attended by participants from palm oil producing countries in the Asia Pacific, Latin America and Africa; UN agencies; the private sector; associations of smallholders; scientists; producers of other major vegetable oils; media; national and international NGOs; and major palm oil consuming countries.

The main focus was the visible progress recorded by the palm oil industry on sustainability. As it is not meant to be a certification scheme, the framework is to act as the primary reference for the palm oil sector, led by the CPOPC.

Another important aspect highlighted steps to make this framework a basis for better governance of the palm oil sector; a foundation for transformative dialogue on sustainability for all vegetable oils; and collaboration needed at regional and global levels.

UNDP Indonesia’s Senior Management Advisor/Head of Environment Unit Dr Agus Prabowo emphasised the contribution of sustainable palm oil in transforming the food system. He observed that the framework reflects the excellent work of CPOPC as an example of the transformation that the world needs to improve the state of the food system.

He recalled the message of the UN World Food Summit – ‘making our food system more sustainable’ – and said the framework is a powerful way to change course and make progress towards all 17 SDGs. He added that this distinctive approach and perspective in specifically addressing the SDGs is greatly appreciated.

Solidaridad Managing Director Dr Shatadru Chattopadhayay expressed strong support for the framework. He suggested two pathways for the common framework to go further, by taking the government to government and business to business approach respectively.

He underscored that it is important to have a level playing field for all oils and fats industries and oleochemicals in Asia, to prevent discrimination against palm oil. In this respect, the framework could provide a platform for dialogue with India, China, the European Union, Africa and South America.

The CPOPC Secretariat will continue to strive for the ultimate goal of the GFP-SPO – to start a collaboration with relevant stakeholders, including other producers of vegetable oils, to make sustainability the norm.

The way forward is to co-create solutions by strengthening sustainability standards for the palm oil sector and other vegetable oils in a spirit of partnership, while rejecting any unilateral decision on what is considered sustainable or not.

As the framework is centred in the UN SDGs, there is a clear need to introduce it to all relevant UN bodies and agencies, and to forge further dialogue with all parties to realise a global standard for all oils.

CPOPC

Jakarta, Indonesia

This edited version was compiled from reports posted at:

– https://www.cpopc.org/the-launching-of-global-framework-principles-of-sustainable-palm-oil/

– https://www.cpopc.org/category/pressroom/

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 19th, 2021 in Issue 4 – 2021, Sustainability No Comments

Musim Mas has partnered with Nestlé and AAK to address deforestation in Aceh, Indonesia. Such multi-stakeholder collaborations are essential for achieving the transformational change necessary to foster a deforestation-free supply chain.

Creating meaningful change will require Musim Mas to navigate some of the challenges that come with a vast supply base. But doing so will unveil best practices that can be shared with peers – furthering industry-wide efforts to make sustainable palm oil the norm.

Efforts are being made to engage independent smallholders in this process. They join private sector actors, NGOs, suppliers, financial institutions and the local government in playing a key role in supporting a forest-positive future.

About 40% of Indonesia’s palm oil is produced by smallholders. As the biggest and fastest growing group of producers, they are expected to occupy more than 60% of the cultivated area by 2030. Therefore, achieving ambitious deforestation and sustainability goals would be impossible without engaging them.

To further its own traceability efforts, Musim Mas has prioritised collaboration with smallholders, who provide 40% of its production volume. It is estimated that up to one million farmers currently participate in the company’s supply chain.

The Musim Mas Sustainability Policy – which lies at the heart of its endeavours – was updated in September 2020 to reflect a strict stance on the 2025 targets of NDPE – No Deforestation, No Peat and No Exploitation. The policy also lays out a renewed social commitment to improve the livelihood of smallholders and their communities.

Above all, palm oil production is a people business. Implementing the Supplier NDPE Roadmap has already facilitated engagement with more than 32,000 independent smallholders, with more to take place in the coming years. Prioritising multi-stakeholder collaboration in the Aceh-Leuser Ecosystem, Siak and Pelalawan regions, Musim Mas is supporting smallholders and their livelihood, while targeting a more sustainable palm oil future.

However, there are several obstacles to overcome. Most smallholders have inaccurate land titles or lack them altogether. Because they are not bound by contracts or they do not have a permanent relationship with continuous sales to mills, data collection on this group has proven to be a challenge.

Smallholders are farmers with less than 25 ha of planted oil palm. In Indonesia, they only manage 2 ha per household on average, often relying on family to fulfil labour demands. While scheme smallholders are bound by contracts and don’t have the autonomy to work with a mill operator or agent of their choice, they do have a high level of access to assistance from government agencies, businesses or cooperative societies.

This level of access to assistance schemes is uncommon for independent smallholders. They are also associated with smaller yields and less regulatory adherence to certification schemes like those of the RSPO and ISPO. Without government or organisational assistance, they face a lack of access to technical advice and market data. All these factors compromise productivity and sustainability efforts.

Perhaps most importantly, independent smallholders face difficulty in securing loans or capital. With such resources not readily available, smallholders are less likely to achieve – or even want to achieve – sustainability certification. Musim Mas has recognised that it is best to focus efforts on livelihood and people, so that sustainability improvements may follow.

Solutions to problems

With productivity rates as much as 45% below company production levels and their distance from supply chain sustainability efforts, smallholders require much support when it comes to sustainable palm oil production.

When they face concurrent issues like poverty, gender inequality, limited education and a lack of resources, sustainability isn’t often a top priority for smallholders. As such, Musim Mas’ solutions are oriented around independent smallholder success, with the understanding that this forms a basis for improvements to come.

Partnership with IFC

This understanding was the catalyst for Musim Mas’ partnership with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group. Following a 2013 diagnostic study on smallholders, a pilot programme was launched in 2015.

The project initially engaged smallholders who supply the company’s mills, assisting them to overcome issues faced in their journey towards sustainable palm oil production. Centred on the pillars of environmental, business management and social support, the programme has provided smallholders with invaluable knowledge and has taught them new ways to secure financial assistance.

The success of the pilot programme led to a modified version being implemented in several mills and supplier mills in Riau, one of the top supplier provinces with 23% of total crude palm oil procurement. The company has since extended the programme to include independent smallholders in the neighbouring areas of Aceh and South Sumatra.

Priority landscapes

Musim Mas has further identified four priority landscapes, where projects have been implemented to support the intersections between biodiversity, food security, livelihood and forest well-being.

In Aceh, Riau, South Sumatra and West Kalimantan, support is being provided to smallholders who do not have the resources and capacity to make sustainability improvements. This includes those who have limited access to knowledge, are uncertain of land legality, and are unable to access government support.

In South Sumatra, an Extension Services Programme has engaged 395 smallholders for training on Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) since December 2017. Separately, in partnership with Rainforest Alliance, a project was completed in 2019 to address sustainability issues common to independent smallholders. This in turn paved the way for a jurisdictional approach and future sustainability efforts for the regency in North Sumatra. This programme, also conducted with Rainforest Alliance, has trained 525 smallholders.

While it only makes up 5% of Musim Mas’ supply base, West Kalimantan was selected for the establishment of a Smallholder Programme in November 2019. In addition, the company facilitated a partnership with Earthqualizer on an agroforestry training project in 2021. Helping to balance forest conservation with economic development, the project has educated suppliers, smallholders and local communities on land legalisation, forest management practices and sustainable land-use business models.

Smallholder Hubs

With the awareness that smallholders are indispensable when it comes to achieving sustainable production goals, Musim Mas has built upon the partnership with IFC to establish Smallholder Hubs since 2020. To date, these have been set up in Aceh Tamiang, Aceh Singkil and Dayun, Siak. The Smallholder Hub is a platform where palm oil companies can share their expertise and resources to train independent smallholders, regardless of who they sell to, within a specific district.

Designed to address some of the constraints faced by smallholders, these hubs work to advance GAPs, facilitate sustainable plantation management, and enable access to financial and market opportunities. To date, this programme – Indonesia’s largest and most ambitious initiative – has reached more than 35,000 independent smallholders.

Due to its unique history, biodiversity and the fact that Aceh contains 87% of the Aceh-Leuser Ecosystem, the province has been prioritised for Smallholder Hubs. Ongoing deforestation has signified a high-risk landscape, further demonstrating the need for intervention. With risk comes potential for opportunity, which is why one Smallholder Hub was launched in Aceh Tamiang and another in Aceh Singkil, in collaboration with General Mills.

The Smallholder Hub in Aceh Tamiang has trained more than 73 village agriculture officers and 95 smallholders. Consistent with that of other Hubs, the curriculum covers GAPs (such as fertiliser management and integrated pest management); financial literacy; and NDPE. As part of the Inisiatif Dagang Hijau (Sustainable Trade Initiative) in Indonesia, the multi-stakeholder partnership has played a key role in the implementation of the Green Growth Plan across commodities in Aceh.

Similarly, in Aceh Singkil, the Smallholder Hub has produced 75 trained village officers and 310 smallholders. With the local government and General Mills as partners, the Hub has provided insight into the importance of land legality, and demonstrated how permits, land title certificates and Surat Tanda Daftar Budidaya (Cultivation Registration Letters) are essential for sustainable management of oil palm farms.

In spite of complications brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic, the Hub and support from the Earthworm Foundation have still been able to engage smallholders, hold multi-stakeholder workshops, and promote best practices to address deforestation as well as labour and social issues.

The third and most recent Smallholder Hub was a result of Musim Mas’ partnership with AAK and Nestlé. Funding during the first two years of the five-year project from these companies will enable about 1,000 independent oil palm smallholders to enrol in the programme and access training on sustainable agricultural practices. While helping smallholders increase their yield and earnings in existing areas of production, the programme will also reduce encroachment into protected areas.

Nestlé has committed to a deforestation-free palm oil supply chain by 2022; therefore, this partnership is essential in keeping planting within concession areas, minimising deforestation and protecting Aceh’s rainforests. Furthermore, it supplements governmental efforts to curb deforestation rates in the Leuser Ecosystem – the rate has already dropped sharply by this year, by more than 81% of the 2018/19 level.

Social and sustainability benefits

Indonesia is home to more than 2 million smallholders. The formation of cooperative societies has enabled them to benefit from support from other farmers, as well as to enhanced access to superior seeds and governmental replanting subsidies. This has pushed the best interests of the smallholders forward, while contributing to Musim Mas’ sustainability goals.

In the Aceh region alone, 100% of suppliers have an NDPE policy or have adopted the Musim Mas Sustainability Policy. Several of the UN Sustainable Development Goals are also supported in these efforts:

On the ground, these benefits are evidenced by stories like those of Heddie Munthe, a smallholder who accessed microfinancing to support her fertiliser purchases; or Lagut, a smallholder worried about seed purchases, who obtained governmental replanting subsidies.

Whether it is finding support to broker a deal with Unilever, implementing GAPs to increase yields and income, or encouraging female farmers to take on decision-making roles in a male-dominated industry, there is no shortage of successful case studies in the Musim Mas programmes.

If Musim Mas is to achieve NDPE compliance and a more sustainable palm oil supply base by 2025, it is crucial that no stakeholder group gets left behind. Efforts to engage smallholders are essential, as these bring together multiple players within a landscape – buyers, suppliers, brands, NGOs and civil society organisations. More importantly, synching industry efforts with local government initiatives ensures the best outcomes.

Ultimately, by supporting a diverse group of smallholders and their needs, Musim Mas will be one step closer to a fully traceable supply chain, while helping the industry to make sustainable palm oil production the norm.

Musim Mas

Headquartered in Singapore, Musim Mas is a privately owned, vertically integrated company involved in each point of the palm oil value chain.

By gofb-adm on Wednesday, September 29th, 2021 in Issue 3 - 2021, Sustainability No Comments

Palm oil production forms the backbone of economic activity in many Indonesian communities today. The sector holds vast potential to alleviate poverty by providing employment and raising income levels, thereby improving living standards.

With increasing scrutiny of human rights and labour issues in the palm oil industry, it is crucial for producers to assume full responsibility for sustainable practices, including improvements to social infrastructure in smallholder communities. There is also a need to measure and validate the progress made.

Musim Mas, one of the largest palm oil corporations globally, has long worked on improving the social needs of smallholders in Indonesia, including those in remote areas. The community development programmes cover education, healthcare services, infrastructure, disaster relief measures and environmental conservation. This has benefited farmers, children and teachers, as well as the environment.

The company has also been collecting vital data to measure the efficacy of its social development programmes, based on its updated Sustainability Policy launched last year. Its inaugural Social Impact Report (SIR), released in May this year, includes a comprehensive Social Impact Framework (Figure 1). The SIR will serve as a guide in reviewing strategies and efficiently focusing resources on programmes that have the biggest impact on improving quality of life.

The success of the programmes is indicated by these main findings of the SIR:

Supporting smallholders

A key aspect of the SIR was to look at the impact of the programmes on smallholders, who play a pivotal role in the company’s supply chain. Smallholders, defined as individuals with farms smaller than 25 ha, are estimated to cultivate around 40% of Indonesia’s oil palm planted area.

Musim Mas works with more than 1 million independent smallholders; its scheme smallholders were also the first to be RSPO-certified in 2010. The company has implemented two programmes for this group – Koperasi Kredit Primer Anggota (KKPA, or Smallholders’ Oil Palm Development Programme) in 1996; and Kebun Kas Desa (KKD, or Village Oil Palm Development Programme) in 2000.

The KKPA is a primary cooperative credit scheme that provides smallholders with practical support, including bank loan guarantees, agricultural training, and the transfer of quality seeds and fertilisers. The scheme targets individual smallholder family units that manage 2 ha of land or less. To get farmers on board, Musim Mas staff went from house to house to explain the benefits of the scheme. They also helped with administrative requirements to obtain land legally, including applications for identity cards.

The KKD, meanwhile, is tailored for holdings under communal ownership and partnership. This outreach initiative promotes economic independence in villages involved in oil palm cultivation; it also aims to improve social conditions in communities in surrounding areas.

Training is provided to growers – both men and women – as part of the KKPA and KKD programmes. In 2019, Musim Mas conducted 132 training sessions to enhance skills and knowledge. With this, as well as access to higher quality seeds, smallholders have been able to increase the yield of fresh fruit bunches. In 2019, farmers involved in both programmes produced an average of 22.9 tonnes/ha/year – or 22.2% higher than the average RSPO-certified smallholder at 18.8 tonnes/ha/year.

Smallholders under the Musim Mas programmes also enjoy an average wage of 4,343,773 Rupiah (~US$310) per person/month. This is more than 60% higher than the minimum wage in Riau Province of 2,662,026 Rupiah (~US$190). With better income, many farmers have been able to ensure that their children complete higher education.

Rural development measures

Education is fundamental in paving the way to improved livelihoods and social mobility. Since 2002, Musim Mas has been supporting children’s education across Indonesia through the Yayasan Anwar Karim (YAK, or Anwar Karim Foundation); this was set up in memory of the late founder of Musim Mas. The YAK has facilitated his passion for providing quality education to children and youth, among other social welfare activities. In 2019, the operating costs of Anwar Karim schools exceeded 16 million Rupiah.

To date, Musim Mas has built and funded 20 learning units, comprising nine kindergartens, nine primary schools and two secondary schools. Of the 5,983 students enrolled, 47% are girls. In 2013, Musim Mas built the first secondary school at PT Guntung Indamannusa; construction of the second school was completed in 2019 at PT Musim Mas.

Quality teaching jobs are also offered, especially to those from the local community. The schools have received an ‘A’ grade from the Education Ministry. Musim Mas takes pride in providing education for rural children and improving the welfare of teachers, thereby creating a positive learning environment.

Musim Mas is further dedicated to improving infrastructure in remote communities and workers’ compounds. Projects to date include access to utility supplies for more than 13,000 households; construction of roads, mosques and religious centres; provision of free healthcare services at 26 clinics; and upholding of food security.

Fire prevention strategies

Musim Mas takes a serious stance on fire prevention and a deforestation-free supply chain. Forest fires and haze pollution have been a long-standing problem in Indonesia. Musim Mas has therefore rolled out special programmes on sustainable farming policies and fire-free villages. It operates a strict zero-burning policy at all new developments and during replanting, and maintains teams of highly-trained firefighters at each of its plantations. The company’s fire patrol teams and fire monitoring towers enable the early detection of fires.

As part of its Fire-free Village Programme, Musim Mas conducted 148 training sessions at 74 villages covering 458,361 ha in 2019. The topics included alternative land clearing methods and fire prevention, monitoring and suppression. The SIR found that local communities have adopted non-fire farming methods, ever since they began to understand the impact and danger of forest fires. Over the years, there has been an 85% drop in the number of fire incidents within Musim Mas’ concessions – from 89 in 2015 to 16 in 2019.

To combat forest fires beyond its concession areas, the company sees the importance of working with other stakeholders and supporting local communities in adopting alternatives to the slash-and-burn method for land clearing. As a founding member of the Fire-free Alliance – a multi-stakeholder platform set up in 2016 to support the commitment to a haze-free ASEAN by 2020 – Musim Mas has shared information and resources toward a lasting solution.

As a leading sustainable palm oil player, Musim Mas recognises its responsibility and influence in continuing to improve the social and labour conditions of local communities and workers within the industry. The impact can be widened through multi-stakeholder initiatives with government bodies, industry stakeholders and civil society organisations.

Musim Mas

Headquartered in Singapore, Musim Mas is a privately owned, vertically integrated company involved in each point of the palm oil value chain.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Sustainability No Comments

The release early in March of Greenpeace’s report ‘Certified: Destruction’, which was critical of the certification systems for forest and ecosystem risk commodities, has shifted the focus to the role of certification on the sustainability agenda.

The report had sought to ‘assess the effectiveness of (mainly voluntary) certification for land-based commodities as an instrument to address global deforestation, forest degradation and other ecosystem conversion and associated human rights abuses (including violations of indigenous rights and labour rights)’.

The certification schemes Greenpeace reviewed included the International Sustainability & Carbon Certification; Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance and UTZ; Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO); Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO); Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO); Roundtable for Responsible Soy; ProTerra, Forest Stewardship Council; and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification.

Greenpeace concluded that, while some certification schemes have strong standards, implementation has been weak, having failed to address deforestation and ecosystem destruction, and resulted in the ‘greenwashing’ of products.

‘The weaknesses and flaws identified in the certification schemes assessed in the report make it clear that certification should not be relied on to deliver change in the commodity sector. At best, it has a limited role to play as a supplement to more comprehensive and binding measures,’ it said.

Is Greenpeace throwing the baby out with the bathwater?

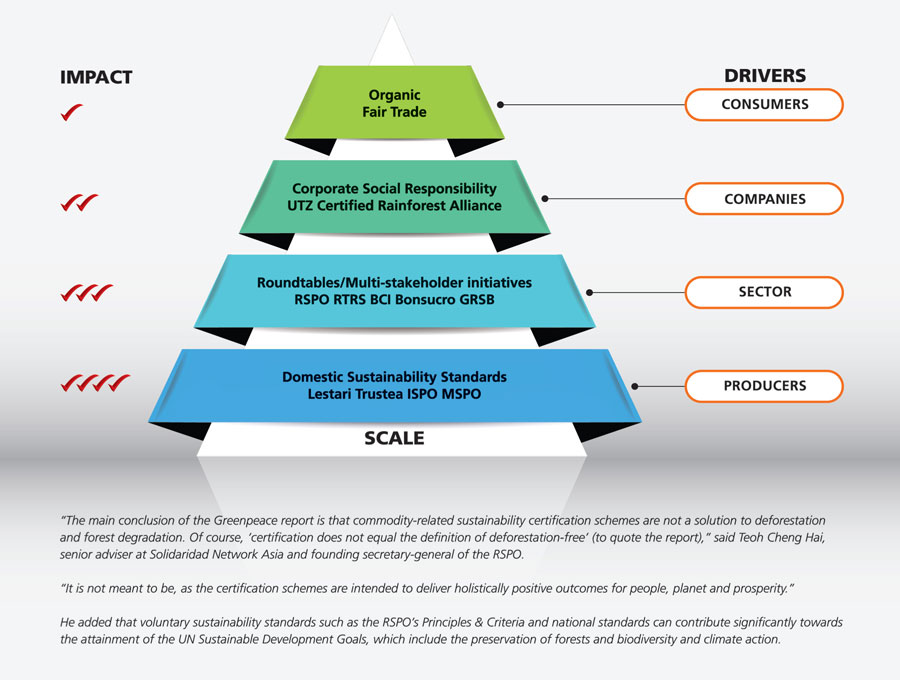

“The main conclusion of the Greenpeace report is that commodity-related sustainability certification schemes are not a solution to deforestation and forest degradation. Of course, ‘certification does not equal the definition of deforestation-free’ (to quote the report). It is not meant to be, as the certification schemes are intended to deliver holistically positive outcomes for people, planet and prosperity,” said Teoh Cheng Hai, senior adviser at Solidaridad Network Asia and founding secretary-general of the RSPO.

He added that voluntary sustainability standards such as the RSPO’s Principles & Criteria and national standards can contribute significantly towards the attainment of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, which include the preservation of forests and biodiversity and climate action.

Development of concepts

Global civil society organisation Solidaridad Network subscribes to the view that certification alone is insufficient to achieve sustainability goals. In a 2017 article, Honorary President Nicolaas Roozen had noted that many farmers and companies were already moving beyond certification towards more ambitious post-certification approaches, as the concept had turned out to be an expensive affair with low premiums that often did not reach farmers.

He explained that the sector-wide engagement process of certification – often called roundtables – is but one layer in the “pyramid of change” towards sustainability (see diagram).

The pyramid is a visual representation of the history of the certification process, which had started in the 1980s with consumers driving the demand for certification for organic products, followed by the fair trade system – initiated by Roozen – to improve terms of trade for farmers in developing countries. Both concepts were successful in raising awareness, but the market segments for fair trade and organic were limited at just 3-5%.

“From the perspective of transformative change in the sector, they didn’t make a difference … I think the main obstacle is, of course, the higher price for the consumer,” said Roozen.

Next came the corporate social responsibility (CSR) concept, driven by companies instead of consumers. Companies rebranded their products by adding a sustainable, social and ecological dimension to their marketing and sourcing. Examples include Rainforest Alliance and UTZ, which merged in 2017.

The third layer in the pyramid is the voluntary roundtable process involving sector-wide engagement, which saw the emergence of various roundtables for palm oil, soybean, beef and other commodities.

“The characteristic of a roundtable process is that the sector as a whole is engaged with a sustainability agenda and creates a platform for creating criteria and practices for sustainable sourcing and production. This is an even higher level of commitment and goes deeper into the supply chain [with] a sector commitment expressed by the relevant players of a specific supply chain,” Roozen explained.

“This concept of a roundtable, of stakeholder engagement, offers the opportunity to create scale because the big companies are on the table and are trying to improve and create better practices for the supply chain – not for a specific segment of the product but for the entire sector.”

At the bottom of the pyramid is the development of national standards (such as the MSPO and ISPO), which has made Roozen most excited, as it involves a commitment to sustainability by producer countries and producers.

“What started small scale with consumer preferences could expand its impact through the CSR and roundtable processes. My understanding is that the real change-maker that leads to transformative change is the national standard. Decisive for upscaling sustainability is local ownership and the commitment of local governments to transform the sector to move to more sustainable production, addressing domestic issues and challenges,” he said.

However, national standards are often seen as lower than Western standards.

To this, Roozen put forward Solidaridad’s twofold strategy of “raising the bar, raising the floor”, which is a smart mix of intervention. To illustrate, raising the bar here refers to extending support to smallholders to be included in the RSPO, while raising the floor refers to having the European Commission recognise the importance of national standards such as the ISPO and MSPO.

“One commitment for now is to switch from one-sided focus on the RSPO and give more value and importance to national standards, starting from these keywords. It starts with the recognition that, at the end, national governments have the authority, capacity and responsibility to address issues in their own sector. This is not a foreign agenda but a domestic one. It starts with the acknowledgment of the relevance of the national standards,” he added.

Furthermore, Europe’s imports of palm oil represent only 6% of global production and consumption, making it highly unlikely for this market to effect sector-wide transformation.

“The differentiator for successful transformation will be local ownership and engagement of the main – the most important – consumer countries. In the case of palm oil, they are India and China,” said Roozen, stressing that it is crucial to move from a Western-dominated agenda to local ownership and commitment, supported by demand for sustainable products in the global market.

Common agenda?

India and China are the world’s leading buyers of palm oil.

In 2020, India and China took up 31.4% of Malaysia’s palm oil exports. The EU followed in third place with 11.2%.

“If you don’t get a commitment from India and China to a sustainability agenda for palm oil production, then it’s a lost cause. That’s the way of thinking,” said Roozen.

The good news is, China and India are looking at the sustainability agenda.

India is the first country to recognise the MSPO as equivalent to sustainable, says Shatadru Chattopadhayay, Managing Director of Solidaridad Asia. The country has also set up the Indian Palm Oil Sustainability framework to create social, economic, environmental and agronomic guidelines for palm oil production and trade.

Similarly, interest in and awareness of sustainable palm oil is growing in China, not just because it buys a lot of the commodity but because of its investments in oil palm planting in Africa, said Teoh.

Apart from having national standards, there is also a need to rethink the earnings model of farmers as the way forward in upscaling sustainable agribusiness, said Roozen.

“What changes the world, if you look at the history of addressing social issues, is creating a business case for farmers that enables them to produce in a sustainable way and earn a living,” he said.

For example, the main driver of child and forced labour is the farmer’s inability to afford higher cost of labour.

“If you change the earnings model, he can have better return and income, he can have mechanisation and replace child labour with machinery and technology.”

In changing the perception of palm oil, Roozen said producers and naysayers must define a common agenda, starting with two statements. First, the contribution of the palm oil sector in eliminating poverty. And second, the commodity’s relevance as an affordable cooking oil for the poorest segments of consumers, owing to its high levels of productivity.

“Greenpeace has never made those statements … On those two basic elements, you can define a common agenda. Otherwise, you will always have discussions that are fruitless and will not connect people to address a common agenda,” he added.

Source: The Edge Malaysia Weekly,

March 29 – April 4, 2021

By gofb-adm on Sunday, July 18th, 2021 in Issue 2 - 2021, Sustainability No Comments

A new United Nations report warns that 12.5% of all plant and animal species face extinction because of a systemic failure to address climate change. A separate report from the UN flatly states that nations are ‘nowhere close’ to the level of action needed to fight global warming.

Scientists have weighed in on the issues and warned of a ghastly future and identified the problems as being ‘compounded by ignorance and short-term self-interest, with the pursuit of wealth and political interests stymying the action that is crucial for survival’.

These reports are hardly surprising. Over the past 40 years, wildlife populations have declined by an astonishing 60% as the world’s richest countries continue to fail the fight against climate change.

A historic ruling by a Paris court could, however, set a precedent for climate action. The court convicted the French state of failing to address the climate crisis and not keeping its promises to tackle greenhouse gas emissions.

France is the perfect example of a country’s failure to address climate change and biodiversity despite big pledges and commitments on paper. No other country exemplifies this ‘ghastly future’ where short-term self-interest is placed before the good of the common.

As a political and economic powerhouse within the European Union (EU), its failure to meet previous commitments presents a challenge to the EU, as the union makes new commitments towards fighting climate change and protecting biodiversity.

In a nutshell, France capitulated to the demands of its rapeseed farmers and decided to ban palm oil as a feedstock for renewable energy. This should have been a warning for conservationists as France, the second-largest domestic producer of rapeseed oil, has seen dozens of native bird species decline up to 66%.

The threat of extinction in the EU due to agricultural activities is not confined to France. The environmental impact of pesticides on biodiversity had been pointed out by the Pesticide Action Network-Europe in its report from 2010. Renewed calls for the EU to act against pesticides have been ignored even as information links the decline of insects to the future of our planet.

Pesticide use in French agriculture ‘has meanwhile exploded’ over the past decade. But rather than address its accountability for biodiversity in member-states, the EU is extending the self-interest of its members by picking on imported commodities through de facto bans on these commodities, including the plan to phase out palm oil for biofuels.

The move was decried as discriminatory by palm oil producing countries and quite frankly, will prove to be an inconsequential move towards fighting climate change or protecting biodiversity in Southeast Asia.

The problem with the EU’s proposal to phase out palm oil as a biofuel is that a mere 4% of global palm oil production is used as EU biofuels. The European Parliament has grossly over-estimated its influence in protecting tropical forests in the top palm oil producing countries, Indonesia and Malaysia.

EU conundrum on imported rapeseed

Meanwhile, the focus of the EU on palm oil as a scapegoat for climate change and biodiversity is a dangerous distraction which should be blamed for the union’s failure to address both meaningfully.

The EU has only recently acknowledged that the popular replacement for palm oil, which is soybean, as having a devastating impact on diverse and carbon- rich regions in South America.

For example, one-fifth of EU soybean imports originate from razed forests in Brazil, where deforestation has risen to a 12-year high. Although the EU is slowly admitting that soybean imports must be scrutinised, it also plans to enact the controversial EU-Mercosur free trade pact which will heighten imports from the region.

The fact is, climate change and biodiversity do not hinge on single commodities. While it can be argued that soybean or palm oil producing countries face high rates of deforestation and biodiversity loss, the same can be said for other nations which produce vegetable oils.

If all vegetable oils were to be included in the EU’s assessment of biofuels for sustainability, the inclusion of rapeseed or its GMO version, canola, would drastically change the dynamics of these conversations.

For instance, Canada and the EU lead the world in rapeseed production. Both these nations, and countries like Australia which contribute 53% of EU rapeseed imports for biofuels, are encountering extreme rates of deforestation and biodiversity loss.

Australia, the only ‘developed’ nation to feature on WWF’s most recent deforestation report is also home to the ‘functionally extinct’ koala bear. According to conservationists, the iconic marsupial’s population is so low it cannot survive another generation in the wild. In Canada, a report detailing the threats of its endemic species highlighted that 40% of the 308 plants, animals and fungi are imperilled, with eight already extinct.

Ultimately, the EU’s phase-out of palm oil for biofuels will increase pressure on feedstocks, as the reliance on agricultural products like rapeseed accelerates biodiversity loss and emissions in countries at home and abroad.

Considering the call of the various bodies at the UN, it is encouraging to see the EU, as the global antagonist against palm oil as food and fuel, backpedal its position.

The EU-ASEAN Joint Working Group on Palm Oil seems to have agreed for the moment, that the environmental impact of all vegetable oil crops, whether for food or fuel or cattle feed, needs to be addressed in a global standard for sustainability. This approach is long overdue.

The latest statement from COCERAL, FEDIOL and FEFAC, which collectively represent EU grains and oilseed trades, nailed the historical problems on the head when they said: ‘Stigmatising and discriminating a specific commodity or origin has not shown so far to be effective for reducing deforestation. Complex situations cannot be tackled with oversimplification, false or inaccurate allegations.’

This fact should dominate the next discussion of the EU-ASEAN Joint Working Group. The livelihoods of French rapeseed farmers and those of oil palm farmers can hopefully be seen in a holistic context that includes birdlife in Europe and orangutan in Southeast Asia, as part of a global drive to fight climate change.

Robert Hii

Source: Global Policy Journal, March 15, 2021

This is a slightly edited version of the article, which is available at: https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/ 15/03/2021/case-global-sustainability-standards-vegetable-oils

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Sustainability No Comments

The palm oil industry has become a major contributor to the economies of Indonesia and Malaysia over the past few years. In Indonesia alone, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics, 48.4 million tonnes of palm oil were produced in 2019, approximately 60% of the world’s supply. More than 60% of the palm oil was exported, valued at almost US$16 billion.

Further, according to the Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs, the expansion of oil palm plantations has helped lift more than 10 million Indonesians out of poverty since 2000. The industry supported the livelihoods of 23 million people in 2018, 4.6 million of whom are involved in independent smallholdings across the country.

However, along with other agricultural commodities, such as rubber, soybean, coffee and cocoa, palm oil production has been linked to legal and illegal deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss, greenhouse gas emissions, and violations of labour and community rights. Consuming countries as importers of ‘forest risk commodities’ have frequently been held responsible for driving these impacts and for importing deforestation through commodity supply chains.

Stakeholders along the supply chain have responded via various means, including through policy measures to reduce deforestation, forest degradation and associated emissions. As an example, through its second Renewable Energy Directive (RED II), the European Union (EU) plans to phase out eligibility of biofuel feedstock to EU renewable energy targets where they are assessed to be the cause of high indirect land use change.

Palm oil is currently classified in this category and since around half of the EU’s palm oil imports are for biofuel, the regulation could affect a significant proportion of palm oil exports to the EU from Indonesia. The Indonesian government is currently challenging the RED II in the World Trade Organisation.

Indeed, in recent years, importing countries, consumers and NGOs have been pressuring palm oil companies and producing countries, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, to step up their sustainability game. Many stakeholders have responded with efforts to show that a sustainable palm oil industry, which provides win-win outcomes for markets and the environment, is not only possible but also constitutes the ambition moving forward.

The Indonesian government, for example, has accelerated the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification in the past couple of years. In addition, the government has issued a national action plan for sustainable palm oil and adopted a moratorium policy banning new expansion of oil palm plantations. Based on an analysis by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Indonesia’s total deforestation fell by 20% following the launch of the moratorium policy in 2011.

Subnational jurisdictions at the forefront

In Indonesia, some subnational governments have been very active in supporting the national government’s policies on sustainable palm oil. According to the Civil Society Coalition for Improving Palm Oil Governance, up to December 2019, six provinces and eight districts have responded positively to the national government’s policies by issuing bylaws or making public commitments about the moratorium.

A few subnational governments have also been embracing the jurisdictional approach, which seeks to address palm oil and deforestation related issues at the subnational level by involving all relevant stakeholders. For example, Seruyan District in Central Kalimantan is working with the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to ensure all palm oil producers in the district comply with RSPO Principles & Criteria.

This approach is also pursued by the state of Sabah in Malaysia, which aims to be 100% RSPO certified by 2025. In East Kalimantan, the Berau District Government is collaborating with the Nature Conservancy, Climate Policy Initiative, and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit on a low-emission oil palm development programme. In North Sumatra, the South Tapanuli District Government is collaborating with the United Nations Development Programme and Conservation International Indonesia to form a multi-stakeholder forum on sustainable palm oil.

These subnational initiatives, led by the provincial/state and district-level governments, hinge on the role local governments can play given their authority and legitimacy to promulgate regulations and policies for sustainability. The subnational governments, for example, have the authority to issue certain permits on the use of land and establishment of plantations, and to monitor and enforce laws and regulations underpinning the transition of the entire jurisdiction towards sustainability.

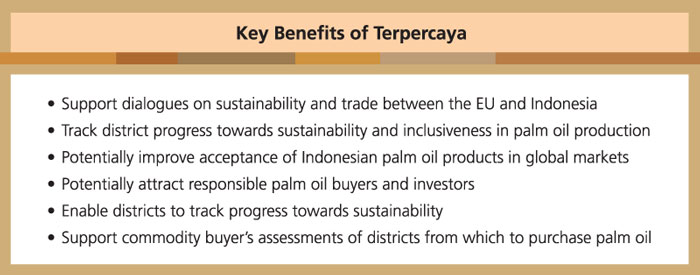

Further, the subnational initiatives can potentially bring in multiple benefits – not only by attracting palm oil buyers and investors who care about sustainability, but also by supporting national and subnational governments in making progress towards development targets and international commitments, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement.

Tracking jurisdictional sustainability

With support from the EU, the Indonesian Ministry of National Development Planning (Bappenas), which coordinates the planning and monitoring of the nation’s development and SDG implementation, is spearheading an initiative to implement a framework to monitor and measure the performance of districts in achieving national priorities and the SDGs.

The framework resulted from an initial 2018-19 study, led by the European Forest Institute (EFI) and the Indonesian NGO Inobu, which assessed the feasibility of mapping and screening Indonesian districts based on their commitment and performance regarding sustainability of forest and agricultural production, especially palm oil.

The framework, known as the Terpercaya approach, takes its name from an Indonesian word meaning ‘trustworthy’, as it aims to generate objective and transparent information and analysis. Through a collaborative process involving the multi-stakeholder Terpercaya Advisory Committee, composed of the government, private sector and civil society stakeholders, the initial Terpercaya study developed 22 indicators.

The indicators, covering environmental, social, economic and governance aspects, are based on Indonesian laws and regulations, aligned with national priorities and the SDGs, and supportive of the national policies to promote a sustainable palm oil industry, such as the ISPO standard.

By covering entire districts, the Terpercaya approach should help create a level playing field for all producers, including certified and non-certified actors, companies with and without sustainability commitments, and smallholders of all types.

The approach will be particularly advantageous to smallholders, as it provides them with the chance to better access the markets for sustainably produced palm oil. At a broader scale, the Terpercaya approach should also assist the districts’ efforts to increase competitiveness and attract sustainable, green investment.

Terpercaya data platform

In 2020, Bappenas, EFI, Inobu and several other partner organisations collected data for the 22 agreed indicators and established a national database containing information on the sustainability of Indonesian districts.

A user-friendly public Terpercaya data platform showcasing this information will be launched soon. It will monitor and measure sustainability progress against baseline data and allow users to compare district progress in various dimensions of sustainability. Linking the platform to supply chain information to help commodity buyers assess districts from which they are purchasing palm oil will also be possible.

The platform will benefit different users. At the subnational level, the platform will enable district authorities to track progress towards sustainability and inclusiveness in palm oil production. For example, it could encourage district authorities to resolve land tenure issues and accelerate ISPO certification for smallholders, thus complementing existing commodity-based certification systems.

At the same time, the central government can use the monitoring system to programme incentives and support for local governments to achieve sustainable and inclusive agricultural development and SDGs. In this context, Bappenas plans to use the Terpercaya framework to guide fiscal transfers to districts under the special allocation fund for agriculture.

Further, the Terpercaya platform could help improve acceptance of Indonesian palm oil products in global markets and ensure that civil society, consumer countries, investors and commodity buyers are well informed about the progress made by Indonesian districts. The Terpercaya platform could also serve to contribute to constructive and open dialogue.

The Terpercaya platform could additionally support the private sector in meeting their sustainability commitments. For example, international buyers of palm oil and investors could use the information presented in their sustainability due diligence assessment, to help determine with which districts to interact.

At its core, the Terpercaya approach aims to help resolve trade-offs between palm oil production and environmental protection by promoting market access for sustainable palm oil, utilising government capacity, and supporting broad-scale achievement of national priorities and internationally agreed SDGs.

The approach’s unique selling points include the objective information it showcases, the collaborative development of indicators, and its alignment with the national context, especially the existing policy and legal frameworks. In principle, such an approach could be easily implemented in countries other than Indonesia.

For now, the primary focus is to build a larger and stronger collaboration around Terpercaya, involving a broader range of stakeholders in Indonesia and beyond. This is needed to ensure that the approach reaches its maximum potential in advancing sustainability in the palm oil industry and maintaining benefits from production and trade of a valuable commodity.

In this context, the recently initiated EU-funded Keberlanjutan sAwit Malaysia dan Indonesia (KAMI) or ‘sustainability of Malaysian and Indonesian palm oil’ project aims to support policy dialogue between relevant stakeholders in the EU, Indonesia and Malaysia on the sustainable use of palm oil.

The project also encompasses support for collection and dissemination of agreed, objective information on subnational level sustainability performance to reinforce dialogue and better communicate on the production of palm oil.

Through KAMI, support for Terpercaya will continue and experience gained over past years will be built upon in developing jurisdictional indicators of sustainability performance aligned to EU policy. Through collection and dissemination of associated information, Terpercaya will transition from a national to an international approach.

Satrio Wicaksono

Forest and Land Use Governance Expert, EFI

Anang Noegroho

Director of Food and Agriculture

Ministry of National Development Planning, Indonesia

Silvia Irawan

Executive Director, Inobu

Josi Khatarina

Senior Advisor, Inobu

Jeremy Broadhead

KAMI Project Manager, EFI

By gofb-adm on Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 in Issue 1 - 2021, Sustainability No Comments

Malaysia has succeeded in uplifting the lives of people in rural communities through oil palm cultivation. It has also put in place legal, financial, environmental and social measures to ensure that production of its palm oil meets the principles and criteria of sustainable palm oil, under the framework of a national certification scheme.

Read more »