The Flood, Part 2

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2018, Publication No Comments

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2018, Publication No Comments

From 1965 to 1967, in addition to bringing to completion our programmes for planting, roads and buildings, we were also very preoccupied with the erection of our factory. At that time, the only company which could build a standard turn-key palm oil mill on contract, was Messrs Stork of Amsterdam.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2018, Markets No Comments

In the wake of the financial crisis in 2008, it emerged that the Greek economy was in much worse shape than anyone had thought. Foreign debt that was out of control, plenty of red tape and profligate spending on welfare, alongside poor tax collection, were the factors behind this.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2018, Markets No Comments

Hungary, with a population of 10 million, is a landlocked country in central Europe. Nearly one-fifth of the population lives in Budapest, the capital city.

A few years after Hungary joined the European Union (EU) in 2004, declining exports, reduced consumption and fixed asset accumulation hit its economy hard. During the 2008 financial crisis, the country entered a severe recession, with its economy shrinking by 6.4% – one of the worst contractions in its history.

A downward spiral set in. Banks gave out fewer loans and investment activity plummeted. This, along with growing price sensitivity of the consumer, caused a decline in consumption, resulting in job losses and further reduction of economic activity. Inflation did not rise significantly, but real wages dropped.

After the 2010 election, the economy began to recover with a big boost from exports, especially to Germany. In 2011, a growth rate of about 1.7% was achieved. At the end of the year, the government turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the EU for financial support, to refinance its foreign currency debt and future bond obligations. When Hungary rejected the economic policy recommendations favoured by the EU and IMF, talks broke down in late 2012.

In 2016, the Hungarian economy grew by 2%. The government is pursuing two goals in its economic policy: the creation of one million new jobs over the next 10 years; and the transformation of the legal framework to make Hungary ‘the most competitive economy in Europe’.

Pushing on

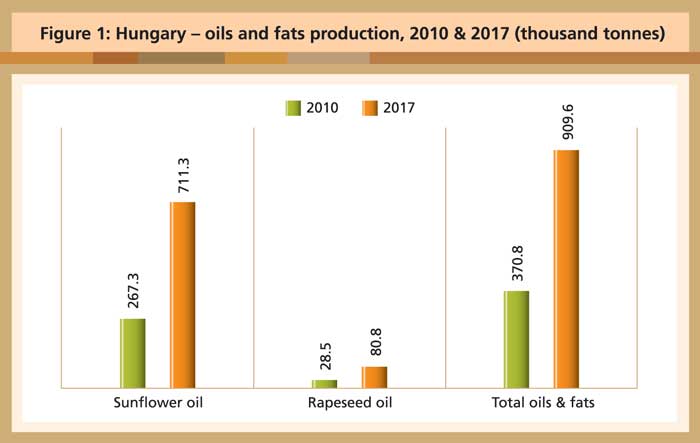

Of Hungary’s production of oils and fats in 2016, 75% comprised sunflower oil. It is interesting to note that domestic production, in general, has been growing significantly in recent years (Figure 1).

Source: Oil World

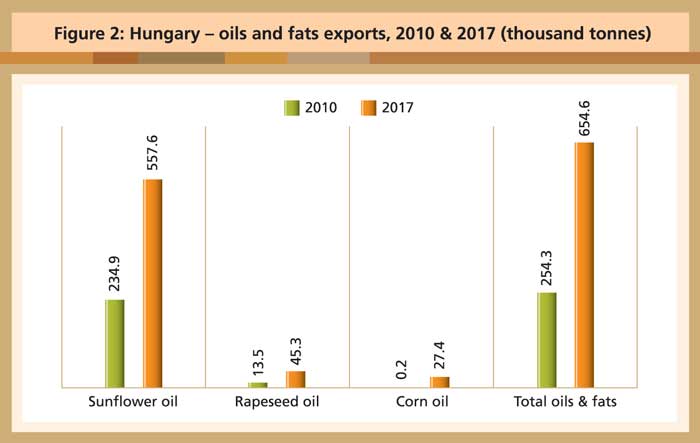

In line with the political goals to push the economy forward, exports have seen impressive growth since 2010. Oils and fats exports more than doubled during this period (Figure 2), carried mainly by sunflower oil.

Source: Oil World

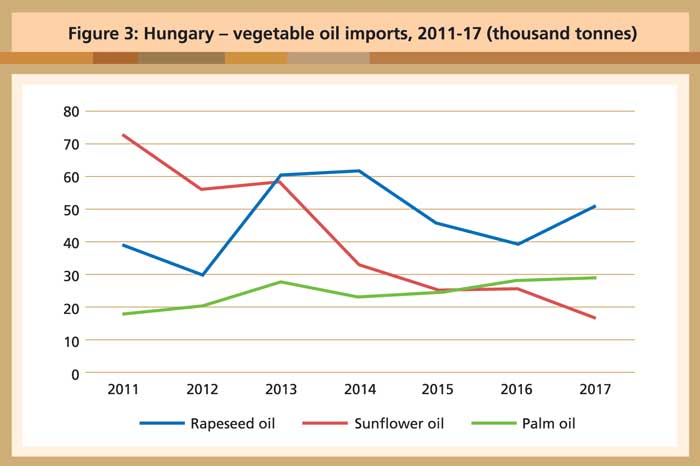

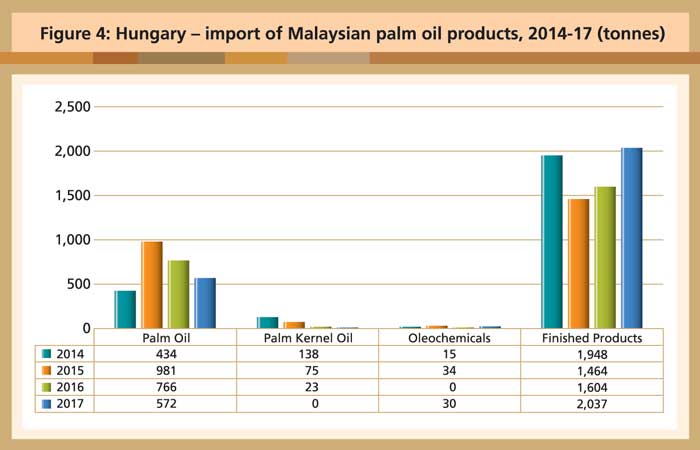

Imports are moving at a much lower level. Intake of rapeseed oil and sunflower oil has fallen in the long-term trend (Figure 3). Only palm oil imports have grown over the last couple of years, with finished products topping the list (Figure 4).

Source: Oil World

Source: MPOB

Hungary’s economic policy appears to be aimed at supporting export industries and substituting imports where possible. At the same time, there is an effort to attract foreign direct investment to grow the employment base.

This approach is manifested in the oils and fats sector as well – domestic production and exports have expanded, while imports have remained relatively lacklustre. With Hungary trying to shape itself into an export base for the EU and eastern European neighbours, there may be a role for palm oil in supplying inputs to processing industries.

MPOC Brussels

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Plantation, Issue 4 - 2018 No Comments

From the 1960s, Malaysia’s oil palm plantations commenced planting with higher-yielding Tenera palms which yielded up to 30% more palm oil per planted ha. At the same time, a new domestic industry sprang up – production of palm oil mill machinery.

By 1974, a further advance had emerged by licensing in-house palm oil refining, fractionating and bleaching. In the 1980s, technology had been developed to transform palm oil mill liquid waste from a costly effluent to a profitable feedstock to generate electrical energy. Production research took a further leap forward by the multiplication of selected palms through clonal technology in the 1990s.

Source:

* https://data.world bank.org/indicator/AG.LND.AGRI.ZS,2015

** https://world bank.org/indicator/AG/LND.FRST.ZS,2015

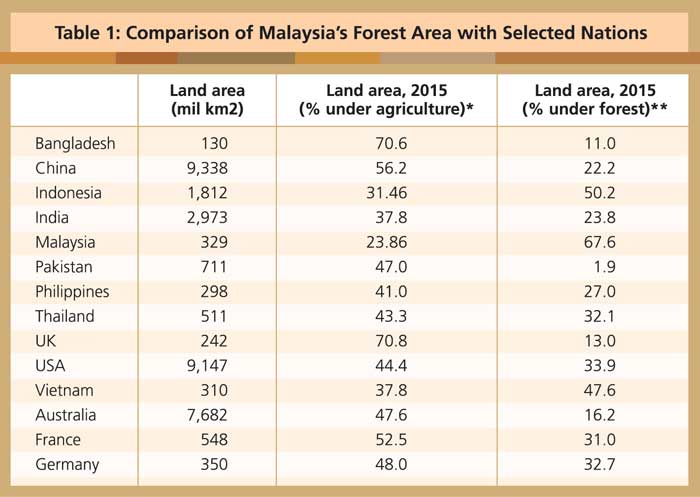

Forest cover

Indonesia, as at 2017, has maintained 50.2% of its land area under forest cover. Malaysia appears to have maintained 67.6% natural forest cover (World Bank data, 2015). Currently, 17.6% of Malaysia’s landmass, or 5.7 million ha, remains undeveloped – less than the existing oil palm planted area of 5.8 million ha (MPOB, Dec 31, 2017).

A Malaysian national policy to preserve 50% (16.4 million ha) of natural forest cover would allow licensing of 11.4 million ha (35% of the landmass) for oil palm plantations, while preserving status quo with Indonesia in relation to Malaysia’s 1992 Earth Summit pledge of 50% forest cover. Malaysia’s all-important plantation economy has consistently emphasised its commitment to reducing carbon emissions and maintaining biodiversity.

The developed world (with some notable exceptions) records about a third of its land area devoted to forestry; the developing world in Southeast Asia records up to half of its land area devoted to forestry. The exception is Malaysia where, in 2015, 67.6% of its land area was shown to be under forest. Have Malaysian land-use policies been targeted by foreign NGOs financed or subsidised by nations which prop up domestic production of oilseeds?

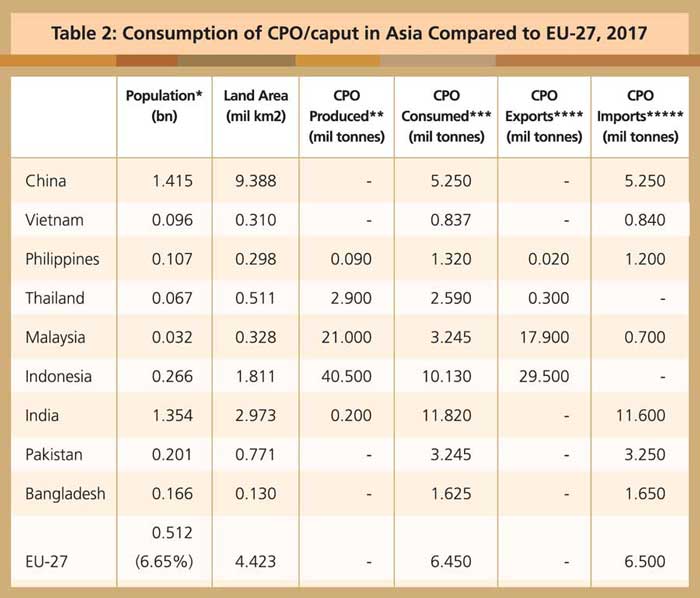

CPO consumption

Halting the 1981-2018 ‘oil palm fever’ has refocused national priorities from plantation investment to maximising the fresh fruit bunch (FFB) and crude palm oil (CPO) production per planted ha, with strong emphasis on product quality and marketing. It marks the end of a 37-year bull run which has seen palm oil increase from 7.8% of worldwide supplies of edible oils in 1980 to 35% in 2017.

CPO consumption/caput/annum was 101kg/caput in Malaysia, 38kg/caput in Indonesia and 13kg/caput in EU-27 in 2017 (Table 2). These figures contrast sharply with the average annual consumption (7.2kg/CPO/caput for the rest of Southeast Asia).

Source:

* www.worldometeters.info/world-population/population-by-country, 2017

** www.indexmundi.com/agriculture/?commodity=palmoil&graph=production, 2017

*** www.indexmundi.com/agriculture/?commodity=palmoil&graph=consumption, 2017

**** www.indexmundi.com/agriculture/?commodity=palmoil&graph=exports, 2017

***** www.indexmundi.com/agriculture/?commodity=palmoil&graph=imports, 2017

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2018, Comment No Comments

With the debate on biofuels recently having taken centre stage, the continued discrimination and denigration of palm oil in retail and by food business operators has shifted a bit out of the focus. It does not mean, however, that the issues have gone away.

In April, Iceland Foods Ltd, the UK’s leading frozen food company and retailer, announced that it would stop using palm oil as an ingredient in its own label food by the end of this year. Iceland linked this to a ‘collapse in orang utan population’ claim. Palm oil has already been removed from 50% of Iceland’s own label range and 130 products are to be reformulated by the end of 2018.

Iceland’s simplistic and deceptive view falls short of addressing the many environmental questions that undoubtedly must be addressed on a global level. Singling out and discriminating against palm oil alone appears to be a marketing stunt, diverting attention from the real issues and based on a number of misleading assumptions.

Earlier this year, Iceland’s decision was immediately criticised by researchers from the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Biology (DICE) of the University of Kent. The researchers underlined that banning palm oil from products was actually a step backwards in the effort to prevent deforestation and to promote sustainability.

The researchers at DICE are working with palm oil certification bodies and companies to improve the way in which oil palm cultivation interacts with the environment. The work at DICE aims at demonstrating the advantages of connecting high-quality rainforest patches in oil palm plantations to allow wildlife to move freely. If the sustainability certification of palm oil became more widespread, this would benefit the environment more than switching to other vegetable oils.

According to the researchers, Iceland should work with the industry to find sustainably sourced solutions, highlighting that ‘environmentally conscious consumers should demand palm oil from certified sources, but avoiding it altogether runs the risk of putting pressure on other crops that are equally to blame for the world’s environmental problems’, such as soybean.

In principle, businesses are free to decide which kind of raw materials they use in their products, and are also free to choose whether or not to use palm oil. However, waging denigrating marketing campaigns and attaching unauthorised labels to food products arguably violates EU law, in particular the Food Information Regulation.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2018, Nutrition No Comments

On Oct 4, 2018, the European Commission (EC) published a draft Commission Regulation amending Annex III to Regulation (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to trans fats, other than trans fats naturally occurring in animal fat, in foods intended for the final consumer. Stakeholders were invited to submit their comments.

The Draft Regulation proposes a maximum limit of trans fats, other than those naturally occurring in animal fat, in food which is intended for the final consumer, of 2g per 100g of fat. Food which does not comply may continue to be placed on the market until April 1, 2021

Trans fats are a particular type of unsaturated fatty acids. In Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 they are defined as ‘fatty acids with at least one non-conjugated (namely interrupted by at least one methylene group) carbon-carbon double bond in the trans configuration’.

Some trans fats are produced industrially. The primary dietary source of industrial trans fats is partially hydrogenated oils. These generally contain saturated and unsaturated fats, among them trans fats in variable proportions (ranging up to more than 50%), according to the production technology used. Trans fats can also be naturally present in food products derived from ruminant animals, such as dairy products or meat from cattle, sheep or goat.

Timeline and details

Article 1

The following conditions shall apply:

Article 2

– This Regulation shall enter into force on the 20th day following that of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.

– Food which does not comply with this Regulation may continue to be placed on the market until April 1, 2021.

– This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all member-states.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2018, Sustainability No Comments

In his closing speech at the 16th meeting of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), held in Sabah on Nov 15, Co-Chair Dato’ Carl Bek-Nielsen issued a call to industry to rise to the challenge of bringing about market transformation.

“Just over 300 years ago, on a foggy night in 1707, English naval officer Admiral Cloudesley Shovell grounded four British warships on the rocks of Scilly. Two thousand lives were lost – they had fallen victim to faulty navigation.

Legend has it that a sailor had warned the Admiral earlier that day that his fleet was dangerously off course. Shovell hanged the sailor on the spot for mutiny. A few hours later, the ships ran aground and Shovell and his men perished in the cold waters. The incident was recorded as one of the greatest maritime disasters in British history.

However, this tragedy inspired a tremendous leap forward in terms of innovation. Just seven years later, it resulted in solving the conundrum of longitude. So, from 1714, both longitude and latitude could be determined, thus minimising the risk of faulty navigation.

Many of us who have come together here in Sabah see the RSPO as a journey of innovation by ‘sustainabilising’ an important commodity.

When consumers, NGOs and public opinion turned to the palm oil industry and said ‘your navigation is faulty – you are off course!’, we could have closed our eyes, blocked our ears and looked the other way. Or like Admiral Shovell, we could have hanged those who spoke up. However, those behind the formation of the RSPO acted differently – they listened.

They took the first difficult steps to acknowledge that change was not just required, it was necessary. Status quo was no longer tolerable. The rest is history, as they say, and here we are 14 years later, with more than 4,000 members committed to this multi-stakeholder approach.

But the RSPO must continue to evolve if it is to remain relevant and achieve market transformation, all the while stimulating the spirit of inclusivity and continuous improvement. With this in mind, I want to touch on the recent Principles & Criteria (P&C) review.

First, a vote of congratulations to all stakeholders who have been involved in this process, for much work, time and effort has gone into this – 18 face-to-face events in 13 countries, six physical Task Force meetings and over 11,500 individual stakeholder comments received.

What’s the net result?

Halting deforestation, protecting and conserving peatland, mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, strengthening human rights, labour rights and obtaining of free, prior and informed consent – these are just some of the key improvements implemented in the draft P&C 2018.

However, much more needs to be done. To be credible and remain relevant, we must also be realistic and not shy away from the fact that we still have a long way to go if we’re to achieve market transformation.

For a moment I therefore wish to be the ‘canary in the coal mine’, so to say – and, like the sailor on Admiral Shovell’s ship, warn all on board this ‘RSPO ship’ that there are signs of us falling victim to faulty navigation.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2018, Sustainability No Comments

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was established in 2004, in response to attacks on the industry on environmental and social grounds. Members include growers, traders, financiers and end users, as well as concerned NGOs. Its aim is to ‘transform markets to make sustainable palm oil the norm’ and to ‘advance the production, procurement, finance and use of sustainable palm oil products’.

The objectives are admirable, but palm oil certified as sustainable by the RSPO constitutes less than 20% of world production, and users have failed to take up more than half the certified oil. Here, I give an outsider’s view on the RSPO’s development, and what the future may hold for the RSPO.

A set of Principles and Criteria (P&C) was adopted by the RSPO General Assembly in 2007, and has been revised twice since then (this paper was written before the 2018 revision was published). Individual plantations and mills are audited against these criteria and, if they meet the requirements, their annual production is certified as sustainable. RSPO membership is voluntary, but on joining, growers have to agree to a ‘time-bound plan’ to become fully certified. Palm oil users can buy certified oil, and mark their products as ‘containing certified sustainable palm oil’ (CSPO).

In 2009, the RSPO adopted a New Planting Procedure (NPP), which requires social impact, environmental impact, high conservation value (HCV) and greenhouse gas (GHG) assessments to be undertaken before a new development. Free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) by local communities to any development is essential.

For sustainable palm oil to become ‘the norm’ a major proportion of palm oil must be sustainably produced and, if the RSPO is to be the vehicle for this, the majority of producers should be members. The reality is that the certified area peaked at 2.77 million ha in 2015 (just under 20% of the global oil palm area), but has since declined. In 2017, the RSPO had 170 member-growers but only 76 were certified.

When the RSPO was established, growers expected that demand for CSPO would be high, and that it would therefore command a premium price. However, in 2014, the premium was only about US$2 per tonne, about 0.3% of the selling price. In 2016, 12.1 million tonnes of palm oil was RSPO-certified, equivalent to 18.3% of world production; but less than half (5.6 million tonnes, 8.5% of world production) was actually taken up. Thus it appears that more than half of the CSPO would have incurred all the costs of certification, but had to be sold without earning even the very small price premium.

With certified area static or declining, and less than 10% of world palm oil production actually being sold as certified, the RSPO has not so far been very successful in transforming the market. Many companies have not joined because they see certification as a cost, without corresponding benefits. Costs have been estimated at US$4-10 per tonne of oil, much more than the current price premium. Several companies have claimed to see increased yields and improved profitability as a result of adopting the RSPO ‘best practices’. However, these practices could be adopted and the improvements obtained without the costs of membership and certification.

Difficulties for smallholders

Globally some 40% of palm oil comes from smallholders, and smallholder development has been a major contributor to poverty reduction in many countries. The RSPO has developed specific smallholder certification procedures, but these were something of an afterthought to the P&C, and independent smallholders in particular are not well catered for. The RSPO has recognised this, and is working on a simplified standard. Worldwide, a total of 295,000 ha of smallholdings have been certified; the majority are in Southeast Asia but, as Table 1 shows, certified smallholders constitute only 3% of the total smallholder area in this region.

Source:

1 www.rspo.org, Nov 2017

2 2016, including Felda – www.mpob.org.my

3 From Corley & Tinker, 2016

4 JH Clendon, pers. comm. , 2017

RSPO member-companies involved in ‘nucleus estate’ schemes are obliged to help the associated smallholders become certified, but many smallholders are not in such schemes. In Malaysia, over 40% are independent. In Thailand, the vast majority of the 300,000 smallholders are independent.

Independent smallholders are supposed to be covered by ‘group certification’. This requires the formation of a group or cooperative, with the RSPO specifying that there must be a group manager who is responsible for certification. This adds a significant cost, but the RSPO operates a ‘smallholder support fund’, and companies buying smallholder fruit may contribute. One study found that independent smallholders in Malaysia were keen to participate in a certification scheme, provided that there was a price premium and the costs were reasonable.

Problems with certification for independent smallholders in Indonesia include lack of land titles, difficulty obtaining good quality seedlings, safe storage and use of pesticides, lack of finance for fertilisers and of knowledge about best use, and inadequate documentation.

The NPP is a significant problem for independent smallholders, as it requires social impact, environmental impact, HCV and GHG assessments. The assumption is that smallholders will be in organised groups or in company schemes, in which case the group manager will arrange the NPP, but not all smallholders are organised in this way.

The NPP must be applied to conversion from other crops (e.g. rubber), as well as from forest. This seems quite unnecessary; any adverse effects of replacing a few hectares of rubber with oil palm will be trivial. An area limit could relieve the majority of individual smallholders of the need to follow the NPP.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2018, Sustainability No Comments

“Judging from the presence of participants from many parts of Europe and Asia, this is indeed a hallmark platform for a balanced debate on the many challenges associated with palm oil today. It is encouraging to see various stakeholders present, and I am glad to be in your esteemed company.

In Malaysia, we are in the midst of creating a new, more dynamic and sustainable era supported by new governance policies, and with many areas being redefined by the current popular government. Among items with top billing is palm oil, a major commodity and a significant contributor to annual GDP.

The organisers suggested that my address should dwell on sustainability goals and challenges, not only within Malaysia and its palm oil industry, but also incorporating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

As a nation, we have already expressed our SDG commitments on issues ranging from climate change and poverty eradication to women’s empowerment. On this note, I am proud to say that these goals are intricately woven into our palm oil industry.

Malaysia has been proactive about sustainability in the palm oil supply chain. One of our plantations was the first to achieve RSPO certification, in August 2008. Malaysia currently accounts for nearly 42% of global production of certified palm oil. This has been volunteered generously by industry members; but, despite our best efforts, the noise of anti-palm oil sentiments continues to ring loudly throughout Europe.

We have stepped up the game and are now marching towards the goal of mandatory certification of our entire palm oil supply chain by end 2019, using the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil certification scheme as the national standard. So, when the Amsterdam Declaration kicks in from early 2020, I hope you will look to Malaysian palm oil for your needs.

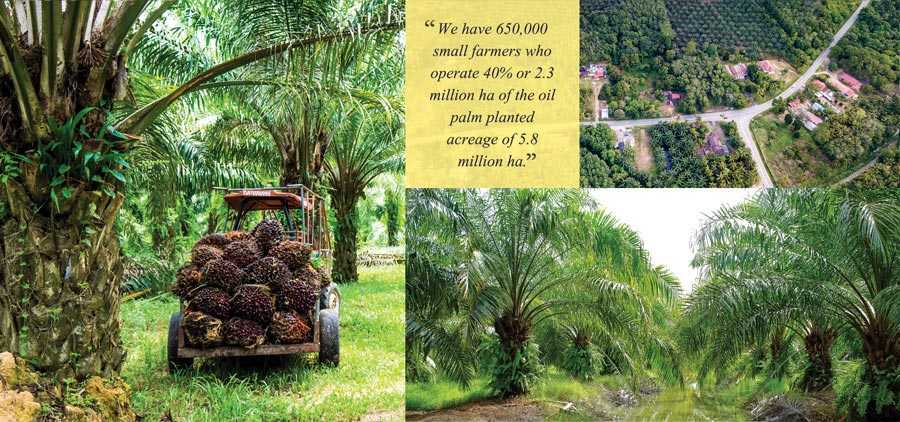

The SDGs do not mince words when they prioritise poverty eradication. In Malaysia, we could not imagine achieving this primary sustainability goal without palm oil. We have 650,000 small farmers who operate 40% or 2.3 million ha of the oil palm planted acreage of 5.8 million ha. This surprises most people, who assume that the Malaysian palm oil industry is run by business corporations.

Our small farmers depend on oil palm for their livelihood and to meet basic needs. They face a very grim future when NGOs like Greenpeace brand palm oil as ‘dirty’. Many activists also have a tendency to tar all sources of palm oil with the same brush.

To the government, oil palm cultivation is synonymous with poverty eradication. Since Malaysia’s independence in 1957, the poverty rate has fallen from over 50% to below 5%. According to the World Bank, less than 1% of Malaysian households live in extreme poverty.

We plan to support the communities and businesses that have made this a reality over the past 60 years. There is more to do. Thus we ask you, especially end users in Europe, to join us in the poverty eradication goals by using sustainable Malaysian palm oil.

How do we achieve this?

Please work with us to improve the productivity of small farms, and adopt small palm oil cluster certifications as part of your corporate social responsibility. When productivity increases within the small farmers’ community, there will be little need to expand into new land for oil palm cultivation. I know that Europe is passionate about rainforests and their mega biodiversity. Being passionate alone will not save these forests – actionable activities will.

Malaysia is talking with the European community, and many positive programmes should fall in place soon. As such, I urge continuous support and collaboration from all – don’t hamper our genuine efforts toward the sustainability of palm oil.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, December 30th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2018, Cover Story No Comments

A controversial Greenpeace film about the ‘plight’ of the orang utan in Indonesia and Malaysia completely ignores the reality on the ground and is actually counter-productive.

I HATE to have to say this but James Corden and Bill Bailey have allowed themselves to be duped by an unholy combination of NGOs and naïve retailers.

I’m referring, of course, to the controversy over a recent film made by Greenpeace to highlight the continuing plight of the orang utan in Indonesia and Malaysia, if land is cleared for new oil palm development.

It’s now getting a huge amount of airtime, as Greenpeace offered the use of the film to British supermarket chain Iceland for its Christmas advert.

Greenpeace has a strong relationship with Iceland, the only UK retailer which has committed to phasing out the use of palm oil in all its own products by the end of the year, on the grounds that its CEO Richard Walker doesn’t know how to tell the difference between certified sustainable palm oil and uncertified palm oil.

(By the way, it’s not difficult, Richard. You just have to pay slightly more for the certified oil than for the uncertified oil – but then your customers wouldn’t like that, would they? And it would be really good if you made sure that the 500 tonnes a month you need were certified as sustainable, not least because a lot of certified oil doesn’t find a buyer at the moment, and is sold as uncertified oil!)

When they checked the film, the regulator of broadcast advertising intervened to stop Iceland from using the film on the grounds that it was “too political”.

And that’s because it was made by Greenpeace for specifically “political” reasons, with no requirement on it whatsoever to worry about being “fair, decent, honest and true”.

This has prompted a massive social media campaign, supported by Corden, Bailey and dozens of equally ill-advised celebs calling for the Rang-tan to be “liberated” from this wicked attempt to curtail freedom of speech.

To be honest, that’s a laugh. The film is unashamedly propagandistic and emotional – as John Sauven, CEO of Greenpeace UK, has explicitly acknowledged.

It focuses on a young girl discovering a baby orang utan in her bedroom after it had been driven out of his forest home. They both have huge, dark brown eyes. It’s well-made, and effective – but deeply manipulative. Why?

Four big, fat, completely mendacious implications. Greenpeace does a lot of good work on palm oil issues in all sorts of different ways, but the story of sustainable palm oil is a complicated one, and it is not helped by willful misrepresentations of this kind.

Bizarrely, Greenpeace knows this as well as anyone. Earlier in November, Greenpeace UK released a video which explicitly acknowledges that boycotting palm oil is the wrong thing to do; that switching from palm oil to other oils can be the wrong thing to do, since palm oil is so much more productive per hectare; and that “growing palm oil without deforestation is possible, and there are growers working that way”.

It then turns up the heat in its campaign against Asia’s leading agribusiness group Wilmar, but does so within the kind of proper contextual background that is so seriously absent in the Rang-tan film. Will the real Greenpeace stand up, please?

More than a million people have signed up to the Rang-tan campaign since then. But it would be so good if we could help deepen their awareness here, bearing in mind that:

At which point, I have to make a declaration of personal and professional interest.

In the first place, Forum for the Future does a lot of work with the oil palm industry, for which we are paid.

Our most important project is based in Indonesia where we’re working with five large palm oil companies as well as a wide range of NGOs and international organisations to address complex labour rights challenges within the sector.

But this is also personal. I act as the independent sustainability adviser on behalf of Forum for the Future to Sime Darby Plantation – the largest producer of certified palm oil in the world.

I’ve watched Sime Darby Plantation in particular, together with other big players in the industry, incrementally get its house in order, in order to be able to sell genuinely sustainable palm oil in Europe and elsewhere, as certified by the RSPO.

None of these companies is perfect. Indeed, I remain a fierce critic of just how long it has taken to sort out some of the legacy issues. There are still far too many laggards in the industry, and a lot of environmental damage is still being done.

But to go on vilifying and demonising such a critically important industry, which continues to move forward on challenges like deforestation and better working conditions, makes no sense whatsoever.

The process of certification through the RSPO is indeed not perfect but it’s the best way we have of sorting out the good stuff from the not-good-enough stuff – even if people like Richard Walker don’t understand that basic reality.

So don’t give in to emotion here. Stick to the facts, difficult and messy as they inevitably are.

Just as you should support the good guys in the oil palm industry, and criticise the bad guys, so you should support Greenpeace in the good work it does, but criticise it when it gets it wrong.

This write up published on 22 November 2018 by Sir Jonathon Porritt* in his blog (www.jonathonporritt.com) was in response to a campaign against the alleged refusal of the broadcasting authority to allow a Christmas TV advert by UK retailer Iceland, from being aired on mainstream channels.

The advert, originally produced as an animated short story by Greenpeace UK and narrated by celebrity, Emma Thompson, tells the story of an orang utan ‘forced from her forest home to make way for palm oil production’. Two other UK celebrities James Corden and Bill Bailey also joined the campaign to lift the alleged TV ban.

*Sir Jonathon Porritt is the Co-Founder of Forum for the Future, UK’s leading sustainable development charity, with over 100 partner organisations including some of the world’s leading companies. He is an eminent writer, broadcaster and commentator on sustainable development, as well as the Independent Sustainability Advisor to Sime Darby Plantation Berhad, the world’s no. 1 producer of certified sustainable palm oil.