Market Updates – Issue 4, 2017

By gofb-adm on Monday, January 15th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Market Briefs No Comments

By gofb-adm on Monday, January 15th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Market Briefs No Comments

Summary

Indonesian biodiesel consumption to drop in H2 2017?

Dono Boestami, chief executive at the government agency Indonesia Estate Crop Fund, expects a slowdown in domestic biodiesel consumption in the last six months of 2017 due to “some technical difficulties”.

In the first six months, domestic biodiesel consumption reached 1.7 million kilolitres. However, this is expected to fall to 0.9 million kilolitres in the second half of the year, resulting in an estimated total of 2.5 million kilolitres in 2017. In the near future, Boestami wants to boost the consumption volume to 3.5 million kilolitres per year.

Through government sponsored programmes, local authorities encourage the production (and consumption) of biodiesel. Considering that Indonesia – which is Southeast Asia’s largest economy –is also the world’s biggest palm oil producer, it can produce palm biodiesel in a relatively cheap way.

Moreover, biodiesel consumption eases Indonesia’s rising reliance on imports of crude oil-based fuel and curbs the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. In the B20 biofuels programme that was launched in 2016, the government set a minimum 20% blend of bio-content in diesel fuel, up from 15% in 2015.

Meanwhile, Fadhil Hasan, board member of the Indonesian Palm Oil Association, said palm oil production will increase to 38.5 million tonnes in 2018, up from an expected 36.5 million tonnes in 2017.

Indonesia’s palm oil exports are expected to rise to 29 million tonnes in 2018, from an expected 28 million tonnes in 2017. Crude palm oil prices are likely to average between US$700 and $710 per tonne in 2017 on a CIF Rotterdam basis.

Source: www.indonesia-investments.com, Nov 3, 2017

US anti-subsidy duties hit biodiesel imports

In a final ruling released on Nov 9, the US Commerce Department set anti-subsidy rates in the range of 34.45-64.73% for palm biodiesel imports originating from Indonesia. This was slightly lighter than the preliminary 41.06-68.28% range set in August 2017.

The final duties for soybean-based biodiesel from Argentina were set in the range of 71.45-72.28%, higher than the preliminary countervailing rates set in August 2017. The government of Argentina said it may take the dispute to the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

The issue arose when US biodiesel producers complained about the ‘dumping’ of biodiesel in the domestic market by Indonesian and Argentine exporters. They were alleged to even sell their products below the market value.

Indonesian exporters are able to sell cheap palm biodiesel in the US because the government subsidises production through its B10, B15 and B20 programmes. Under these programmes, diesel is blended with a mandatory amount of fatty acid methyl ester (derived from palm oil). The programmes aim at limiting imports of fuel into Indonesia.

The Trade Ministry of Indonesia had earlier emphasised that the subsidy programme is only meant for biodiesel sold in the domestic market.

Also on Nov 9, Indonesia lost an appeal ruling at the WTO in a dispute with the US and New Zealand over restrictions on imports of food and animal products, such as meat and poultry. Indonesia had been setting import barriers due to health concerns, halal food standards, and to deal with a temporary surplus in the domestic market.

New Zealand and the US took the case to the WTO panel, claiming Indonesia’s move was a violation of their trade agreements. In December 2016, a panel of adjudicators faulted Indonesia, leading to the appeal and the ruling.

Source: www.indonesia-investments.com, Nov 10, 2017

India hikes import tax on edible oils to 10-year high

India, the world’s biggest edible oils importer, has raised the import tax on these products to the highest level in more than a decade, to try and support its farmers. The duty increase will lift oilseed prices and their availability for crushing in the domestic market, helping the country in capping edible oil imports in the 2017/18 marketing year, which started on Nov 1.

India doubled the import tax on crude palm oil to 30%, while the duty on refined palm oil has been raised to 40% from 25% earlier, the government said in an order. The import tax on crude soybean oil was increased to 30% from 17.5%, while on refined soybean oil it was raised to 35% from 20%.

Indian oilseed crushers have been struggling to compete with cheap imports from Indonesia, Malaysia, Brazil and Argentina that have reduced demand for local rapeseed and soybean, even after a steep fall in oilseed prices.

The second increase in import tax in less than three months will push up domestic edible oil prices and support prices of local oilseeds like soybean and rapeseed, said BV Mehta, executive director of the Mumbai-based Solvent Extractors’ Association.

Soybean and rapeseed prices have been trading below the government-set price level in the physical market, angering farmers. India relies on imports for 70% of its edible oils consumption, up from 44% in 2001/02.

Even after the duty increase, India will need to import about 15.5 million tonnes in 2017/18, down from earlier estimate of 15.9 million tonnes, but higher than last year’s 15 million tonnes, said Sandeep Bajoria, chief executive of the Sunvin Group, a vegetable oil importer.

“The duty hike will have marginal impact on imports. India has to import due to huge demand,” Bajoria said.

The government also raised the import duty on soybean, canola oil and sunflower oil.

Source: Reuters, Nov 17, 2017

By gofb-adm on Monday, January 15th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Advertorial No Comments

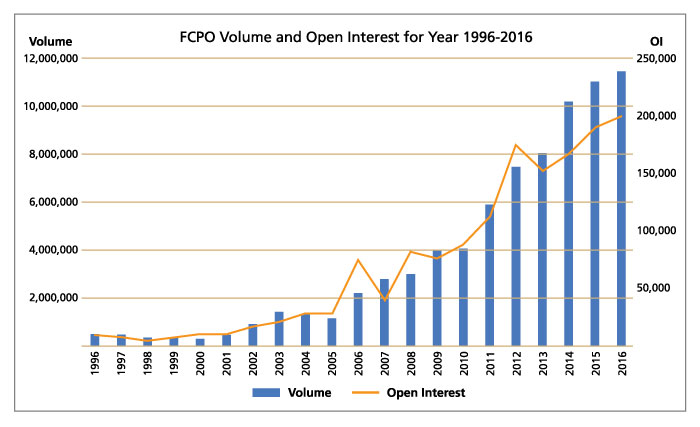

Bursa Malaysia Derivatives (BMD) Malaysia Ringgit (MYR) denominated Crude Palm Oil Futures (FCPO) contract is a global benchmark pricing of Crude Palm Oil market. Since its launch in October 1980, it has become the reference point for major global vegetable oils and fats market players.

The trading volume had increased more than 4 times in 10 years from 2.8mil contracts / 70mil MT in 2007 to 11.4mil contracts / 285 mil MT in 2016. In January – September 2017, we have seen a 4% increase in contracts traded compared to January-September 2016. The market segment trading FCPO consist of 56% institutions, 28% Professional Traders, and 16% retailers.

To compliment FCPO contract, Bursa Malaysia Derivatives had launched the Options on Crude Palm Oil Futures (FCPO) on 16 July 2012. Options are highly versatile instruments that allow a myriad of trading strategies which satisfy different risks appetites and hedging requirements.

In Year 2016, OCPO trading volume was at the historical high. A total of 40,120 lots / 1mil MT was traded. Majority of the trades are done by Institutional Clients through our Negotiable Large Trade (NLT) Facility. The Exchange is actively sourcing for market makers to provide on screen liquidity. With market makers on board, we do foresee that most of the trades will eventually translate into on screen trading and these will then attract the professional traders and retailers to trade OCPO.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, January 14th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Editorial No Comments

2017 has been a busy year thus far for palm oil especially in Europe. Led by health and environmental claims leveled against palm oil, Europe has launched multiple policy threats, which serve possibly to restrict trade in this important commodity.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, January 14th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Publication No Comments

From 1965 to 1967, in addition to bringing to completion our programmes for planting, roads and buildings, we were also very preoccupied with the erection of our factory. At that time, the only company which could build a standard turn-key palm oil mill on contract, was Messrs Stork of Amsterdam.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, January 14th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Branding No Comments

One of the most important questions in branding generally, and particularly so for the edible oils and fats business with its limited branding budget, is: how do I get the biggest impact for my marketing dollars?

The first, and most obvious, answer is to target your marketing strategy. In other words, don’t spend all your efforts on broad and general marketing projects. Instead, target your resources to where your message can have its most useful impact.

In many ways, the rise of targeted marketing in the world of communication parallels technology development in military circles. One example would be the development of gun technology over the past few centuries.

In the 1700s, guns and muskets were not very accurate, with the result being that many shots would be fired, with only a tiny number of bullets doing anything useful for the attacking force. Then came better technology in the later part of the 1800s, in the form of rifles such as the Springfield in the US and the Lee Enfield in the UK.

The latter had a training standard of hitting a 12-inch target at a distance of 300 yards with 15 rounds in the space of 60 seconds (a tactic that became known as ‘the mad minute’). And in post-World War II battles, snipers have achieved targeted kills in excess of 2,000 metres.

What has changed during that time? Human eyesight is the same. The steadiness of the hand of the shooter is the same. The observation ability of the shooter is the same. All that has changed is the technology.

It’s the same kind of story in branding, but swapping rifles for the printing press. A few centuries ago, a basic printing press could produce leaflets, but very few would get to the people who were really interested in their message.

Next came the advanced printing press that produced newspapers in mass quantities and with advertisements. This was an upgrade in terms of cheapness of production relative to the old printing press, but still most advertisements were not going to audiences that were motivated to read them.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, January 14th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Markets No Comments

Malaysia’s small oil palm farmers have combined forces to contest another EU attempt to ban palm oil biofuels. A new campaign has released a digital advertisement to appear across Europe in December, to reject an unjust and discriminatory move to ban palm oil biofuels under the Renewable Energy Directive.

The ban would sentence 3.2 million Malaysians to renewed poverty, noted Faces of Palm Oil, a grouping of agencies that advocate the cause of oil palm smallholders. It comprises the National Association of Smallholders (NASH), Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA), Sarawak Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority (SALCRA), Dayak Oil Palm Planters Association (DOPPA) and the Malaysian Palm Oil Council.

Faces of Palm Oil demands that the European Council rejects the proposal of the European Parliament, and reaffirms Europe’s commitment to Southeast Asia, Malaysia and small oil palm farmers.

NASH president Dato’ Haji Aliasak Haji Ambia said: “Palm oil has allowed us, the rural poor, to develop our own land, lift ourselves and our families out of poverty, and take control of our own economic destiny. A ban on palm oil biofuels would be an all-out assault against the hundreds of thousands of small farmers across Malaysia. The EU will force farmers back into poverty if it bans palm oil.

“NASH and Malaysia’s small farmers will not stand by while Europeans sell commercial products to Malaysians on the one hand, and cut our economic lifeline on the other. It is unacceptable behaviour: the move to ban palm oil biofuels must be stopped immediately.”

FELDA chairman Tan Sri Shahrir Abdul Samad said: “The proposed ban is discriminatory and must be removed. The 112,635 FELDA small farmers and their families demand clear and direct clarification from the EU that palm oil biofuels will not be banned. The Malaysian palm oil industry is an economic lifeline for small farmers; it has lifted their families from poverty to prosperity. I will continue to defend their interests and ensure justice for them in the global markets.”

SALCRA chairman Datuk Amar Douglas Uggah Embas said: “It is unacceptable that European politicians are preparing to put at risk the prosperity, safety and health of 3.2 million Malaysians. Tens of thousands of SALCRA small farmers and their rural communities will suffer if the EU bans palm oil biofuels. We will not allow this to happen.”

DOPPA president Dr Richard Mani said: “Indigenous peoples in Malaysia will suffer if the EU bans palm oil biofuels. Indigenous communities have used palm oil to lift ourselves and our families out of poverty, and build new hope for the future. The EU proposal puts all of that at risk and undermines the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. On behalf of the Dayak planters of Malaysian Borneo, I urge the European Council to abandon this cruel and heartless plan that will only bring poverty back to Malaysia.”

Source: Faces of Palm Oil, edited press release, Dec 19, 2017

By gofb-adm on Sunday, January 14th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Markets No Comments

The job scope and responsibilities of planters have increased dramatically in recent years – all too often, they have to manage a big land area, with lower skilled and less experienced workers. They also have to satisfy the interests of stakeholders, cope with social welfare issues, respond to Environment Safety Health and sustainability auditors, and attend meetings regularly.

As a result, millennials – identified as those born between 1980 and 1995 – are not generally attracted to plantation jobs, with the demanding workload and challenges of multitasking in an outdoors environment.

However, the use of technology and smart phones could counter such reluctance, and enable them to work effectively and efficiently. Tools such as Apps, sensor technology and intelligent logarithm software will assist in quick reference and swift decision-making in daily estate operations.

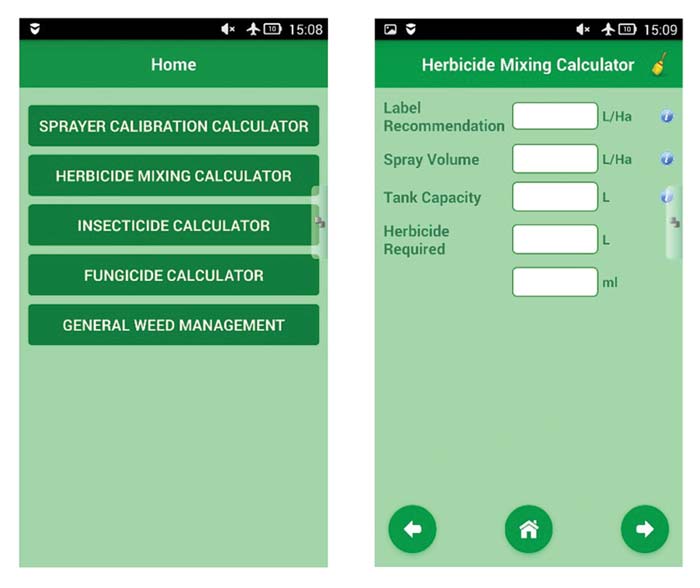

To help with weed management and Pest and Disease (P&D) issues, for example, I have developed an Oil Palm Pesticides Calculator App. This is available free of charge in the Google Play Store. Just search for ‘Oil Palm Pesticides Calculator App’, click on it and download.

The App can be used even when there is no data or Internet connection. It is divided into five sections. The first four are separate calculators for Sprayer Calibration (add the required information to the column in the blue icon); Herbicide Mixing, Insecticide Mixing and Fungicide Mixing.

Calibration of spray equipment and application of the correct dose of pesticides are important for a satisfactory ‘kill’. This will not only reduce over-use of pesticides, but will save costs as well.

The final section in the App is a guide to weeds and P&D management, with the recommended rate being based on general conditions. To control tough problems, the user should consult the R&D department, General Manager or Plantation Advisors.

Devarajen Rajagopal

Developer, Oil Palm Pesticides Calculator

The author is not responsible for any liability, loss of profit or other damage caused directly or indirectly by the guidelines, techniques, recommendations or information in this article.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, January 14th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Markets No Comments

In 1862, the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia formally united under the name ‘Romania’. The country gained Independence in 1878. In 1947, however, a Communist ‘people’s republic’ was formed during Soviet occupation after the Second World War.

In 1965, the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu took power. After he was overthrown in 1989, former Communists dominated the government until 1996, when they were swept from power. Romania joined NATO in 2004 and the EU in 2007.

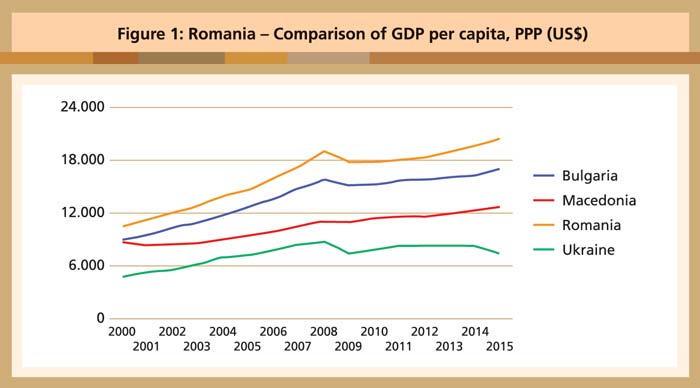

By the end of the Ceausescu dictatorship, the Romanian economy was in extremely poor shape. But, thanks to the support of international donors such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the EU, Romania has succeeded in revitalising its economy. It achieved 3.7% growth in 2015 and 4.8% in 2016. Still, with 55% of the average EU per capita income (2014), it is the EU’s second-poorest country after Bulgaria (Figure 1).

Source: World Bank

Vegetable oils market

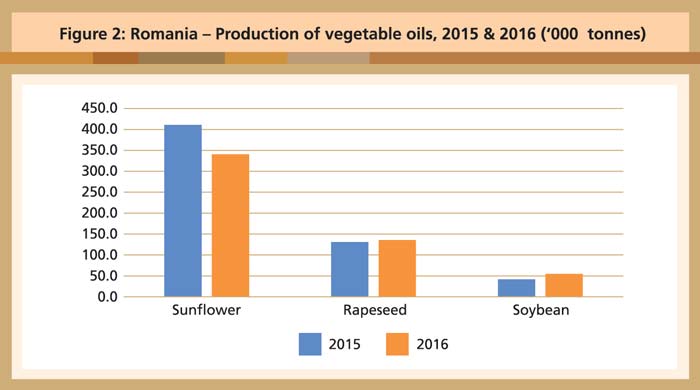

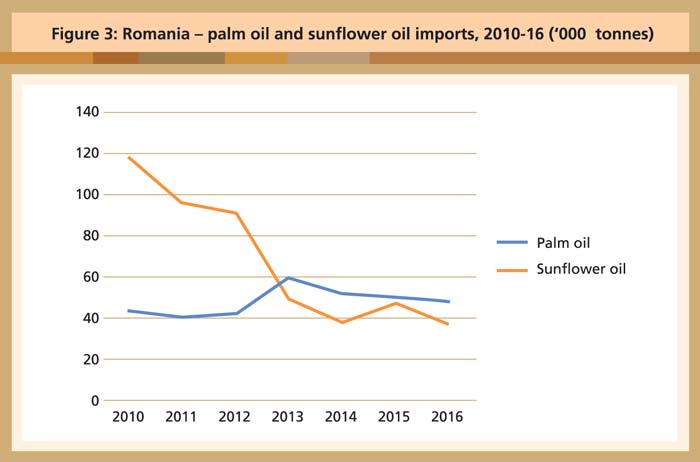

Sunflower oil is by far the dominant commodity in the Romanian market (Figure 2). It is a staple in every kitchen. Palm oil is a major import, surpassing sunflower oil in 2013 (Figure 3).

Source: Oil World Annual 2017

Source: Oil World Annual 2017

By gofb-adm on Sunday, January 14th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Markets No Comments

Poland has come a long way since 1989, when its first free elections were held since the Second World War. With a population of close to 40 million and the GDP at purchasing power parity of around US$800 billion (equivalent to US$21,000 per capita, according to 2012 estimates), the country is ranked sixth in Europe in terms of population and economic prowess.

Poland’s economy is considered to be one of the healthiest of the former Eastern Bloc countries. Its growth rates over the past few years have been among the highest in the EU.

There remains room for improvement, of course. Per capita income is still below the EU average. Other problems persist, including an inefficient commercial court system, rigid labour laws and heavy taxes.

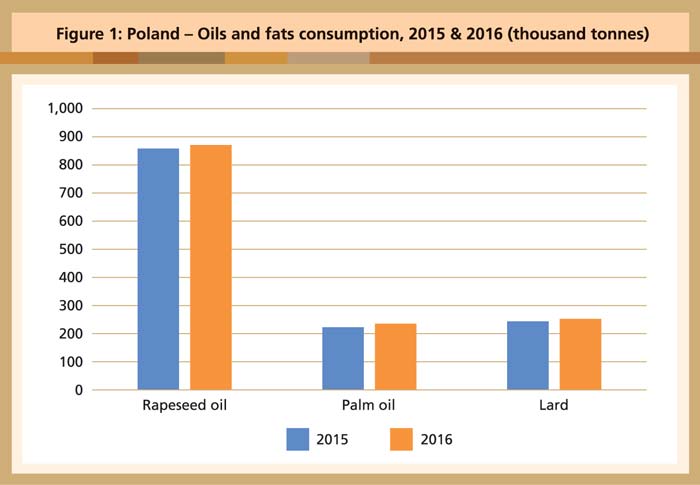

A look at the oils and fats sector reveals that rapeseed oil is the frontrunner in terms of production and consumption in Poland. According to Oil World, the country consumed more than 870,000 tonnes of rapeseed oil in 2016 (Figure 1). Palm oil contributed almost 253,000 tonnes in 2016 – on par with lard, which has traditionally been second-highest in the domestic consumption rankings.

Source: World Bank

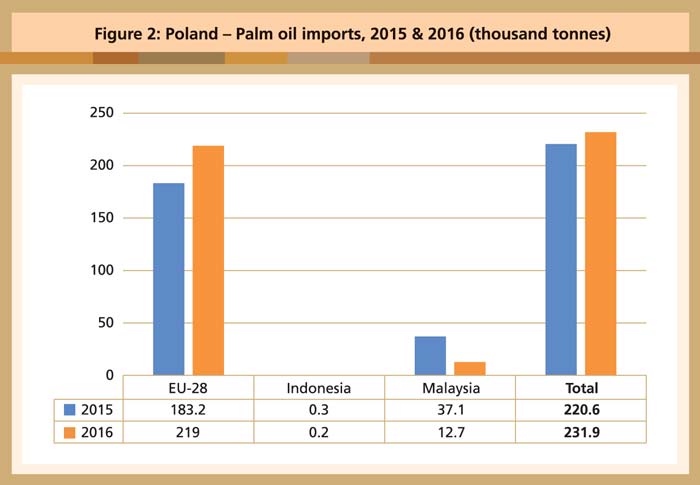

Palm oil is also the primary vegetable oil import into Poland, with Malaysia being the leading exporter. While the bulk of the palm oil imports appear in Oil World statistics as originating in the EU-28 (mainly Germany and the Netherlands), Malaysia is the only producer that also plays a role as direct exporter to Poland (Figure 2). However, recorded quantities in 2016 were only a third of the 2015 figures.

Source: Oil World Annual 2017

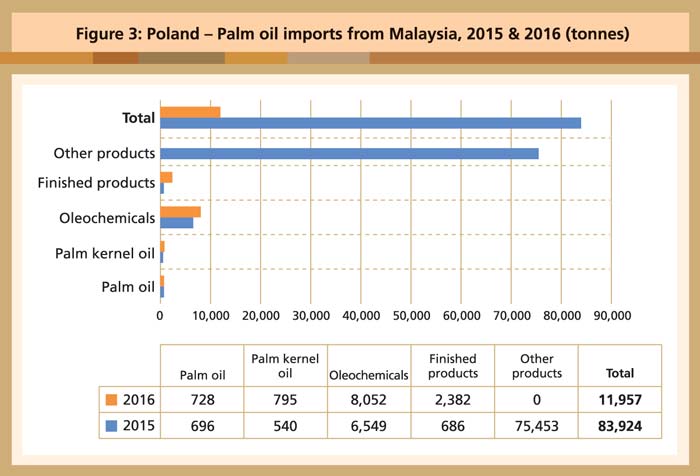

MPOB numbers show a decline in trade activity as well (Figure 3). However, the much lower 2016 total is due to the disappearance of the ‘other products’ category in 2016. The rest grew year-on-year.

Source: MPOB

Good position

Poland´s generally good infrastructure makes it a preferred place for international trade. In particular, the large and modern port of Gdansk on the Baltic Sea is in a position to play a vital role. Strategically located at the centre of Europe, this port lends itself to being the gateway for palm oil imports – not only to Eastern and Central Europe, but to the EU as well. Its neighbour to the west is Germany, the European economic powerhouse. The distance between the two capitals – Berlin and Warsaw – is a mere 550km.

Poland is a potentially lucrative market for Malaysian palm oil, although the commodity faces stiff competition from rapeseed oil and sunflower oil. Other hurdles to overcome are the poor awareness of the Polish consumer regarding the benefits of palm oil; as well as apprehensions connected to environmental issues. Malaysian companies stand to benefit by stressing the positive aspects of palm oil with regard to both nutrition and sustainability.

Poland’s success in its journey towards joining the ranks of modern, market-based economies over the past 25 years has been remarkable. Much has been achieved, and there are no current signs of the country slipping back into economic turmoil.

The incomes and appetites of citizens are growing. The country’s geopolitical positioning between the East and West is ideal. The image of Malaysia is positive, and the relationship between the two governments is good. Opportunities therefore abound for palm oil to reinforce itself as a serious rival to the conventional oils and fats consumed in Poland.

MPOC Brussels

By gofb-adm on Sunday, January 14th, 2018 in Issue 4 - 2017, Markets No Comments

Norway, with a population of about 5.2 million, is bordered to the east by Sweden and on the northeast by Finland and Russia. The Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Programme has classified Norway for many years as the world’s most advanced country. According to the Democracy Index of the British magazine The Economist, it is also the most democratic state.

Norway enjoys a prosperous mixed economy with a vibrant private sector, a large state sector, and an extensive social safety net. Through comprehensive regulation and large-scale public enterprises, the government controls key areas, like the petroleum industry.

Norway is the world’s third-largest exporter of natural gas and the seventh-largest exporter of oil. The latter commodity provides the lion´s share of export revenue and represents about 30% of government revenue. The country is also richly endowed with natural resources such as hydropower, fish, forests and minerals.

After solid GDP growth from 2004-07, the economy slowed in 2008, and contracted in 2009, before returning to positive growth from 2010-14. The government budget remains in surplus.

However, lower oil prices in 2015 may cause the economy to contract as higher production costs in the North Sea deter investment. In anticipation of an eventual decline in oil and gas production, Norway saves state revenue from the petroleum sector in the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund – the Government Pension Fund Global. In early 2017, it was valued at over US$900 billion.

The fund is managed by Norges Bank Investment Management. In its 2016 Fund Report, published in March 2017, it states: ‘The production of palm oil in Malaysia and Indonesia is widely recognised as a major contributor to tropical deforestation. Our initial analysis of the sector resulted in divestments from a total of 29 palm oil companies between 2012 and 2015. The divested companies were considered to produce palm oil unsustainably.’

In 2016, the decision to stay divested was confirmed. The move may have an adverse impact on use of conventionally produced palm oil.

As a country surrounded by the North Sea, Norway differs from other European countries through the dominant role fish oil plays in the economy. Its production volume is second to soybean oil. Moreover, after rapeseed oil, fish oil is the second-biggest import.

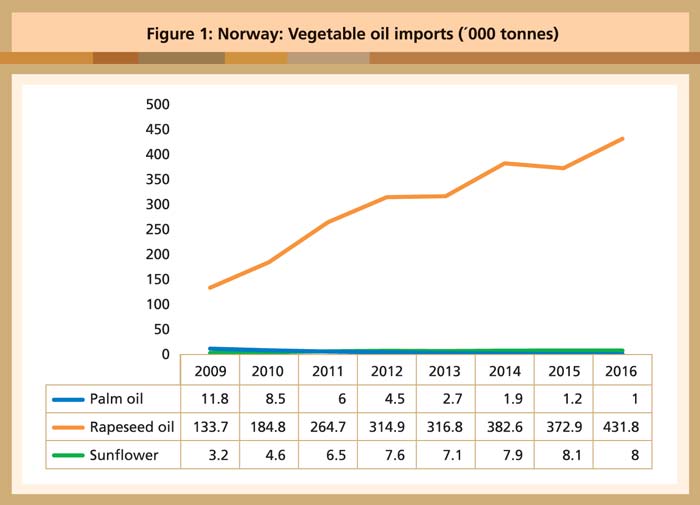

However, the real news regarding the domestic oils and fats sector is the huge drop in palm oil imports. In 2016, the import volume was just a fraction of the 2009 level. This development must be interpreted as a manifestation of the green conscience of Norwegians, who believe the claim that palm oil is ‘bad for the natural environment’. Over the same period, rapeseed imports more than tripled (Figure 1).

Source: Oil World 2017

As a result, the use of palm oil has all but disappeared in Norway.

‘Greener’ Norway

Norwegians are proud of their country´s pristine environment, in particular the fjords and waterfalls. They have a high regard for preserving the global environment as well. The observation that Norway is even ‘greener’ than the Netherlands or France has been borne out in the active anti-palm oil stance that has been adopted.

For example, Clarion Hotels has declared itself “100% palm oil-free”. It is part of the Nordic Choice Hotels Group headquartered in Oslo and operating more than 180 hotels across Scandinavia and the Baltics.

Under the headline ‘Bye, bye palm oil!’ an article on its website quotes Katalin Paldeak, the Group Director of Clarion Hotels in the North, as saying: “… since the 1st of May 2013, all 23 Clarion Hotels in the Nordic region are palm oil-free with regard to restaurant items and products for sale. The reason for this is the increasingly widespread devastation and destruction of the rainforest as [sic] the production of palm oil causes.

“We cannot in good conscience offer our guests food that is made from products that contribute to the devastation of rainforests and people being driven from their homes. Until we can ensure that [what] the palm oil suppliers are seeking to provide us with is being produced in using conscientious and responsible methods, we will pull the emergency brake and remove it from our restaurants, from our sales and from our mini-bars.”

Likewise, the industry news service Food Navigator reported on June 15, 2016, that Norway has become the latest country to sign the Amsterdam Declaration of December 2015. Under this, several European countries have pledged to switch to 100% sustainable palm oil by 2020.

The preamble of the Declaration states in part: ‘Europe is the second-largest global import market for palm oil and home to some of the world’s biggest brands and companies. Europe can be an important ‘game changer’ when it comes to a sustainable palm oil supply chain for the world.’

All this goes far beyond symbolism and must be taken seriously, as the divestments of the Government Pension Fund Global make painfully clear. The Fund has already ended its engagement at Korean conglomerate Posco, owner of Daewoo International, on the basis that Daewoo owns an Indonesian company that is ‘cutting down tropical forests’ to plant oil palm.

If Norway provides any indication, the time when consumers and corporations across Europe start boycotting conventionally produced palm oil on a massive scale may not be far away. The palm oil industry should take heed of this.

MPOC Brussels