Aftermath of the Flood, Part1

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Publication No Comments

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Publication No Comments

From 1965 to 1967, in addition to bringing to completion our programmes for planting, roads and buildings, we were also very preoccupied with the erection of our factory. At that time, the only company which could build a standard turn-key palm oil mill on contract, was Messrs Stork of Amsterdam.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Planter's Diary No Comments

By 1951, Borge Bek-Nielsen (Bek) had completed his engineering degree in Denmark and military service, and was reviewing job prospects. His application to United Plantations (UP) at Ulu Bernam Estate in Perak, caught the eye of Chief Engineer Axel Linquist.

UP had palm oil mills in Ulu Bernam and Jendarata Estate in Teluk Intan, Perak. These were two of 18 palm oil mills in then Malaya. All of them used machinery – and sometimes engineers – supplied by the marine engineering firm Gebr. Stork Apparatenfabriek of Amsterdam, Holland. After World War I, Stork had diversified into the design and manufacture of palm oil mills, many of which were sited along rivers for ease of transporting produce.

Stork’s offshoot expanded rapidly to become a global monopoly. Its customer relations were handled by Jan Olie, a big, genial Dutchman with a great flair for salesmanship. There were no competitors. The world’s big five plantation companies – United Fruit-Central America; Socfin- West Africa; Harrisons and Crosfield; Guthrie; and Barlows-Southeast Asia – were captured one by one.

Unilever Group in West Africa, the Belgian Congo and Malaya was the world’s largest user of crude palm oil – mainly for its soap factories – and provided its own engineering services. But the times were ready for change. UP’s decision to enter the palm oil machinery market was prompted by the retirement of Linquist. His successor as Chief Engineer was Bek, who promptly coined the slogan ‘Made at Ulu Bernam’.

The first company to commission Bek to design and build a palm oil mill was in Kedah. If he left Ulu Bernam by 4pm in his two-seater Citabria plane, he could inspect progress on the ground and return before dark. He designed and erected his second mill near Port Klang with the help of Danish palm oil engineer Worm Sorensen.

Dick Walsh, Senior Assistant at Harrisons and Crosfield’s Sungei Samak Estate, lived on the opposite side of the Bernam River from Bek’s house. Dick resigned from Sungei Samak in 1961 to pioneer an oil palm plantation investment at Tomanggong Estate on Sabah’s Segama River. He sought Bek’s help to build a palm oil mill.

Access to Tomanggong Estate from Sandakan harbour was an overnight journey through the Trusan Duyong, by sea across the delta of the Kinabatangan River, and then up the Segama River. Alternatively, a daily afternoon flight by Borneo Airways Twin Pioneer via Jesselton-Sandakan-Lahad Datu, followed by a short drive to the upper Segama River, allowed one to go down the river for three hours before reaching Tomanggong Estate.

Mill designed in Malaysia

Bek needed to assess the proposed mill requirements through a personal site review. One morning in 1964, he arrived in Jesselton from Kuala Lumpur in time to catch the Borneo Airways’ flight to Lahad Datu. The northeast monsoon was blowing hard down Sabah’s east coast. The weather had somewhat delayed the airline’s schedules, so it was almost dark before he set off downriver.

Tomanggong’s best passenger canoe crew faced rain squalls sweeping up the river. At one point, the canoe rounded a bend to be confronted by a family of wild boar swimming across the river. A passenger grabbed a piglet’s ear and dragged it aboard the canoe. The bowman’s torch reflected continuously off driftwood in the river.

Bek’s fingers grew numb from gripping the side of the canoe as it swerved on its way downstream. The rain didn’t let up. From his seat, Bek periodically bailed the bilge of the canoe’s centre section. He leaned forward out of the canopy to enquire “Berapa jauh lagi, encik?” to be told “Tidak jauh lagi, tuan” and the endless wet journey continued.

At the next bend of the river, the canoe was turned under a large fig tree to answer urgent requests for a relief stop. Everyone stretched stiff limbs. Shortly after, as if by the turn of a switch, the rain died away. Bek’s watch registered almost 10pm. Its luminous paint had all but given up the struggle. The bowman shivered but ventured, “Lima minute lagi, tuan”.

Ghostly shapes of riverside shacks, some with small lamps flickering, showed up in the light of the bowman’s powerful torch. The boat performed a U-turn to tie up at a simple jetty. Passengers scrambled out with wet suitcases and words of thanks. The bowman shook the fuel tank – which swished reassuringly – saying “Satu minute lagi, tuan” before casting off again.

The canoe rounded a final bend, towards a Petromax pressure lamp lighting up a jetty. A figure stood there under an umbrella. The piglet woke up and squealed. “What have you got there, Bek?” called Dick. “Your dinner,” replied Bek. “Next time, can you please make sure I arrive in daylight…”

The next morning, Bek toured Tomanggong’s undulating site comprising fertile volcanic tuff. He collected data on the number of staff and workers’ houses to be served by the mill’s water supply; the electricity and workshop facilities to service the land and tugboat transport services; and the number of palm oil storage tanks required. The situation was not unlike that of a brand-new Ulu Bernam Estate.

Bek’s Tomanggong mill layout would have allowed 5-a-side football to be played around the process floor. It is still there. Bek’s next two factories, at Sabahpalm Estate on the Labuk River and Lai Fook Kim Estate at the Sandakan Peninsula Scheme, were built around modest floor areas.

The Segama mill was Malaysia’s first to be built around two Usine de Wecker, Luxemburg winepresses. These were modified by Bek at Ulu Bernam to double the oil palm fruit throughput of the predecessors, Stork’s 4.5-ton FFB/hour automatic press.

Vickers Hoskins of Perth, Western Australia, provided the smoke tube boilers at half the price of Stork. A Singapore foundry provided the cast steel steriliser dished ends; British factories the compound steam alternator by Belliss Morcom; Switzerland the three-phase gear-motors which powered every machine; Sweden the oil clarification and sludge centrifuges; and Germany the Demag hoists. The Malaysian designed and built palm oil mill had arrived.

The day that Tomanggong’s mill entered service in 1969, Stork closed its Harrisons and Crosfield agency offices, never to sell another boiler, steriliser, automatic press or nutcracker in Malaysia.

In the early 1970s, Bek took over as General Manager of UP from fellow-Danes Ole and Mette Svenssen. He moved into Ole’s newly-completed bungalow at Jendarata Estate, across the road from the UP corporate offices.

He devoted time over the next two decades to design and build another 30 palm oil mills. These included three for UP in Perak. The first was at Seri Pelangi, Bidor, and the final pair – twins, each with a capacity of 100 tons FFB/hour – at UIE, the former Gula Perak, in Tanjung Malim. A replacement unit, six times larger than the original, was built at Ladang Basir, the renamed Ulu Bernam Estate.

‘Made at Ulu Bernam’ – and Malaysia’s first palm oil mill engineer – had come of age!

Moray K Graham

Retired Planter

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Plantation, Issue 1 - 2019 No Comments

A university graduate today has many choices in selecting a career. One of the best would be to work in the plantations industry, which offers a variety of jobs. A long time ago, estates in Malaysia mainly grew rubber, but have since replaced this with oil palm. Most of the plantations are now operated by government investment agencies or family holdings.

To date, oil palm has been planted on about 5.8 million ha in Malaysia, and produces about 20 million tonnes of crude palm oil (CPO) and about 5 million tonnes of palm kernel a year. CPO fetches an average price of RM2,400-2,500 per tonne, while palm kernel has an average price of RM1,800 per tonne. This generates total revenue of about RM60 billion per year. In a good year, the revenue and profit will be higher, as the price can exceed RM3,000 per tonne for CPO and more than RM2,000 per tonne for palm kernel. The kernel is crushed to get oil and cake.

In Malaysia, the yield of the oil palm tree is high, helped by high rainfall of over 2,000mm per year and fertile soils. When mature at about three years old, the oil palm gives an average of one fresh fruit bunch a month, valued at about RM8 per bunch. An efficient management team will try to get the trees to double the number of bunches; this adds to income, while sharply reducing the costs of production per tonne.

At the mill, the palm fruit is cooked and pressed for oil. Again, an efficient management team and workforce will try to increase the extraction rate. The CPO and palm kernel oil are then processed in a refinery and sold to manufacturers of edible and non-edible products.

Buyers use palm oil products in the manufacture of foods, oleochemicals, medicine and cosmetics. Scientists are constantly finding new uses for palm oil in biscuits, chocolate, margarine, medicine, food supplements and detergents, as well as in biofuels.

Manager’s duties

Let’s take a look at the manager’s duties on an oil palm estate of, say, 3,000 ha. Typically, his day starts before dawn, when a driver takes him to the muster ground. The manager stands behind the three assistants and six supervisors, while the 20 mandors read out the workers’ names to take attendance.

The manager looks at the workers in several lines to see if they have turned out with the right shoes and equipment. After receiving quick instructions, they spread out to their areas of work. In the silence of the muster ground, now empty, the manager has a chat with the remaining assistants and supervisors, so all know what they have to do. He always tries to strengthen his team.

As the sun begins to rise, he goes to see the new plantings where the dew is still on the low fronds of young oil palm trees. The rows stretch to the far end and he takes a walk, checking on the circle-weeding done some days ago. Then he is off to see the harvesting. The manager must ensure that harvesting gangs achieve the estimated daily production; he checks for absenteeism, but it is usually low.

He watches a harvester with a sickle at the end of a long aluminum pole, raising it to reach a ripe fruit bunch over six meters above the ground. The harvester slips the blade to the bunch stalk; he steps back, yanks twice and the bunch detaches from the trunk, crashing to the ground. It weighs about 20kg and is worth about RM10. That harvester will cut about 120 bunches a day. That is skilled work.

The manager also inspects other activities around the estate. It could be the manual application of fertiliser. There is a technique to this – the container is swung from waist level towards the back, so that the fertiliser granules spread out in an arc. However, more areas are now being converted to mechanised application using tractors and spreaders. They work faster and help to reduce the need for labour.

Feeder roots take up the nutrients to speed up the growth of the trunk, leaves, flowers and fruit bunches. Fertilisers help increase bunch production and weight. With correct nutrient applications, the trees bear more female flowers. These turn into bunches that are ready for harvest in five to six months.

Such matters are on the manager’s mind as he goes home for breakfast. Yet it would only be 9am, with most of the day still ahead of him. He may again go to the harvesting area or meet the supervisors to hear what they have to say about raising the crop production.

Driving back to the field, he thinks of how the production costs can be reduced if he obtains a higher tonnage of fruit. The figures work in his head, even as his eyes miss nothing. If, for instance, a bridge shows signs of erosion, he gets out of the vehicle and peers under the bridge to assess what it would take to repair it. There is nothing like attending to details.

Once a week, he calls a meeting with the assistants and the chief clerk to review the work done and to check on crop production for the rest of the month. Other matters discussed could be the progress of capital expenditure on new workers’ quarters and the purchase of a road grader and a roller. They have to arrive in time to repair the roads before heavy rains set in. They discuss the date of the next payroll, but this must be kept confidential to ensure security of the cash delivery.

In the evening, the manager may attend a football match between divisions of his estate or against other estates. He may do the kick-off and then watch the game, looking for players who show fighting spirit or leadership qualities. He makes a mental note of their names. They will be on his shortlist for promotion.

By the time he heads home, it is nearly dusk. After a bath and dinner, he reads the newspapers or The Planter magazine published by the Incorporated Society of Planters. He may find scientific, technical and general articles of interest, as well as keep up with the movements of fellow-planters. Today, the news gets to him in many more ways. The fax and the telex have been replaced by the computer, handphone, email and WhatsApp messages.

He must work as a part of a team. For example, he works closely with research scientists as they choose areas for trial plots of new palm progenies and clones. They also look for ways to improve the yield and oil quality, in order to obtain a premium price.

In addition, the manager must know the requirements of sustainable practices as set by the rules of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil and the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil standard. Implementing these might be part of his Key Performance Indicators.

He has many more things to remember and must have updates ready for regular meetings at the head office, which provides support services in accountancy, marketing and sales, human resource management and research.

Before going to bed, he watches the late-night business news on TV. Palm oil prices are moving again. He checks his handphone one last time. There is a request from Marketing for his crop forecast, as well as a question about how much oil and kernel to sell. He notes the urgency, and will reply first thing in the morning. The manager’s views are important for the business.

Mahbob Abdullah,

Director, IPC Services Sdn Bhd

This is an edited version of a paper written for university students.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Techonology No Comments

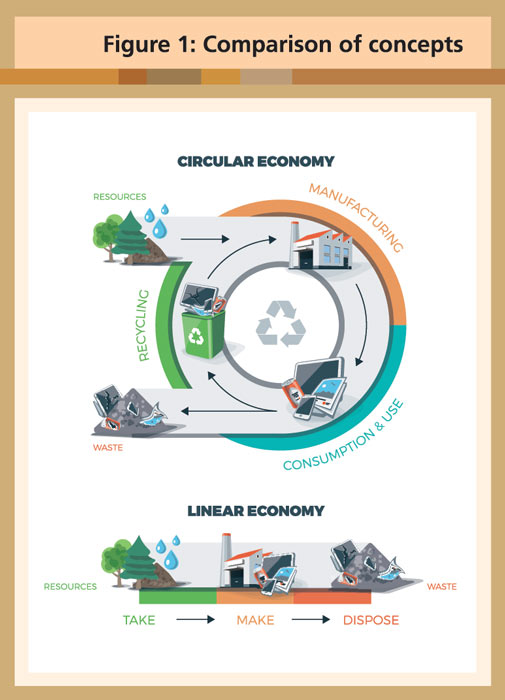

The circular economy (CE) – as opposed to a linear one – describes a regenerative system in which resource use and waste production, emissions and energy waste are minimised by slowing, reducing and closing the energy and material cycles.

This can be achieved through durable design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing and recycling. In practice, recycling – i.e. bringing waste products back into the cycle as secondary raw materials – plays the key role in the CE. This is of particular importance to the palm oil industry.

The linear economy, also known as the ‘throwaway economy’, is the current dominant principle of industrial production. A large part of the raw materials used is deposited or burned according to the life cycle of the products. Only a small proportion is reused.

Expressed as a simple formula, the antagonism between the two concepts is described as take-make-dispose (linear model) vs reduce-reuse-recycle (circular model).

Source: © petovarga/fotolia.com

However, it emerges that there are different schools of thought on the CE. They go by names like cradle-to-cradle, performance economy, biomimicry, industrial ecology or natural capitalism. What all of them have in common, though, is that they aim to:

The CE concept has gained traction in recent years with policy makers and business operators alike. While some researchers caution that it may be just another passing fad, there is no mistaking that the underlying assumptions are here to stay.

The assumptions have been around since the beginning of human economic activity. For instance, traditional agriculture has always been circular. The production energy in the form of human or animal muscle power was fed directly from the cultivated area. Waste like excretions or kitchen litter, and production residues such as straw or ashes from clearing land with fire, were returned directly to production.

Business entities and governments are therefore well advised to take a closer look at the CE. Some countries have already done so. China has had a CE Promotion Law since 2009. The indicator system used to measure its CE is an altered version of the EU´s material flow analysis, which the Chinese have studied extensively and adapted to their own needs.

The European Commission (EC), in its efforts to make Europe’s economy more sustainable, adopted a new set of measures in January 2018, called the CE package. It includes actions on plastics, waste legislation, critical raw materials and a monitoring framework. The EC’s work on the CE is influenced by the International Resource Panel established in 2007 by the United Nations Environment Programme.

In October 2018, the EC’s Directorate General for the Environment organised a CE Mission to Indonesia. This was to ‘build bridges between European institutions, NGOs and companies, as well as the relevant stakeholders in Indonesia interested in the opportunities that the transition to the circular economy brings’. With that, the CE reached the world’s biggest producer of palm oil.

There is not only an environmental case to be made for the CE, but an economic one as well. As British weekly The Economist writes: ‘Environmental problems, such as biodiversity loss, water, air, and soil pollution, resource depletion and excessive land use are increasingly jeopardising the earth’s life-support systems.’

The Economist also observes that more governments have come to realise that investing in sustainability and the CE, in fact, saves money. Take the example of public health: avoiding respiratory diseases by taking measures to improve air quality in cities may turn out cheaper than treating those affected.

The same is true at the corporate level. An increasing number of companies, investment funds and banks, especially in Europe, now accepts that the CE is not a costly fad or simply a way to satisfy the green lobby. Rather, it will improve the bottom line in the long run.

Optimism for palm oil in the CE

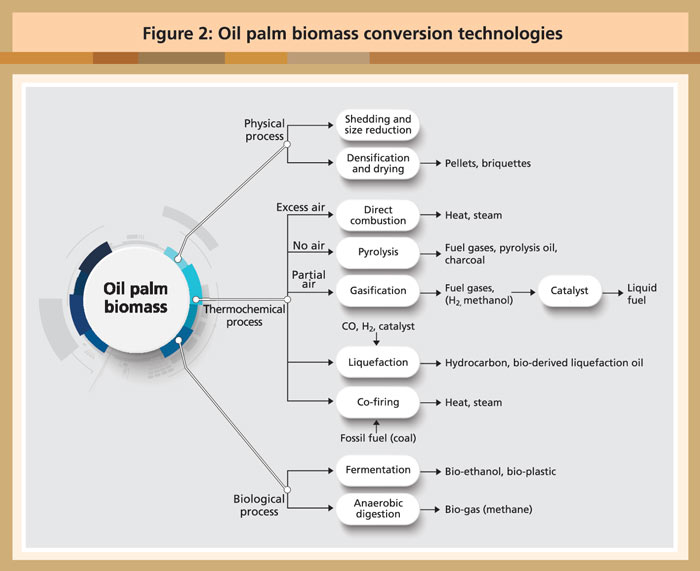

The production of palm oil results in enormous quantities of secondary products – palm oil mill effluent (POME), empty fruit bunches (EFB), palm oil mill sludge, oil palm fronds, oil palm trunks, decanter cake, seed shells and palm pressed fibres. The biomass has massive economic potential:

However, to make a financially feasible shift towards the CE is tricky. A vicious cycle must be overcome. Recycled materials must compete with virgin ones. A successful recycling industry must operate on scale. This would encourage investments in technology and efficiency to make recycling more competitive, and to provide a supply steady enough to create demand.

In a look at why businesses are trying to reduce, reuse and recycle, The Economist points out: ‘Things such as glass, paper and many metals have broken out of this vicious circle, typically once economies spewed out enough of them to make it worthwhile to recycle. Reprocessing technology had often been around for a while – paper was being recycled in the 19th century – but greater availability of source materials encouraged efficiencies. That in turn spurred demand for these materials and itself encouraged further improvements in recovery. In other words, a vicious cycle turned virtuous.’

Given the abundance of recyclable biomass in the palm oil industry, plus the competitiveness of the resulting products, there is ample reason to be optimistic about the potential of the CE approach. There are many different use scenarios on the plantation and at the mill (Figure 2).

Source: Shuit, SH et al.; Oil palm biomass as a sustainable energy source: A Malaysian case study, in Energy 34(2009)

The expansion of palm oil production partly caused the tightening of environmental legislation screws in Europe. The next few years will show if this proves to be a happy coincidence for the palm oil industry after all.

Europe is decarbonising its economy. This means phasing out not only fossil fuels in the long run, but also moving away from first-generation biofuels. Electrical power will not be able to fill the gap, given the scarcity of the natural resources needed to build batteries and the environmental havoc caused by mining them.

Enter second-generation biofuels. European broker Greenea´s vision for the immediate future of biofuels is this:

Malaysia is in the midst of coming on board. Reports indicate that the Malaysian biogas market aims to equip all 447 palm oil mills in the country with biogas plants by 2020. That would be a momentous step forward. And who knows what other opportunities technological innovation might bring?

Just to give an example, the Malaysian Palm Oil Board has been experimenting with microwaves to sterilise fresh fruit bunches instead of using steam. On the one hand, this would eliminate POME (and the chance to capture methane); on the other, it would reduce the water content in empty fruit bunches, thus improving their suitability for use as fuel.

Prospects for palm oil in the energy sector seem promising. Rating agency Fitch has noted that incentives for advanced biofuels under the 2021-30 phase of the EU Renewable Energy Directive would boost demand for recycled palm oil and palm oil waste products, including mill effluent and EFB.

Other opportunities like the collection of used cooking oil (UCO) have not reached the mainstream of the palm oil industry. The European Union already imports UCO at scale. For the first eight months of 2018 alone, industry analyst Argus Media reports imports of more than 235,000 tonnes, four times the 2017 total. Similar developments are observable for biodiesel made from UCO.

Against this backdrop, the time has come for the Malaysian palm oil industry to think harder about the products it could sell. Investment in efficient processes will pay off not only in the production of palm oil, but also in processing the associated biomass.

MPOC Brussels

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Techonology No Comments

Each year, mobile phone brands hold launch events to unveil the latest version of their products and related features. These flashy events are designed to entice users into replacing their devices prematurely. Globally, on average, smartphone owners upgrade their devices within two years. Today, 69% of the world’s population uses smartphones and annual spending on new hardware exceeds US$370 billion.

We are increasingly being propelled into a digital world where new technologies are adopted almost as quickly as these hit the market. However, this situation accelerates the take-make-dispose cycle of the linear economy that has been dominant since the existence of the Industrial Age.

In the linear economy, raw materials are used to make products and discarded as waste after use, without much regard for Nature or the depleting supply of natural raw materials. For example, a company producing light bulbs takes raw materials such as glass or metal to manufacture its products. Light bulbs are sold to customers, who use it until these burn out. After that, the bulbs are disposed as waste.

In order to be profitable, such companies need to produce goods at the lowest cost possible or sell large quantities of the goods. The linear economy does not take into consideration the limited amount of resources available or the output of waste products through creation and use of the goods.

In contrast, the circular economy treats resources as if these are finite, and focuses on building sustainable economic health. The inherent restorative and regenerative design of the circular economy minimises or even eliminates waste, shifting towards the cradle-to-cradle production cycles. This means that product lifetimes are extended by offering options for used items to be returned and component parts repurposed into new products.

Beyond addressing the negative impacts of the linear economic models, the circular economy represents a shift towards a sustainable, resilient business and economic landscape that benefits the environment and society in its entirety. In reference to light bulbs, Phillips now offers the opportunity for companies to lease, rather than acquire, light bulbs over a longer period of time. This creates an incentive for Phillips to produce energy efficient lights, while companies save money on fixed office lighting costs and maintenance.

Traditional companies are attempting to move towards the circular economy. H&M, one of the world’s largest clothing retailers, is working on a strategy to become 100% circular by collecting old clothing in stores for recycling. Since 2013, H&M reports to have gathered more than 55,000 tonnes of fabric.

Disruptive technologies also support the transition to a circular economy by radically increasing virtualisation, de-materialisation, transparency and feedback-driven intelligence. In addition, the shift to a circular economy requires innovative business models that either replace existing ones or seize new opportunities.

The increasing popularity of access-over-ownership business models has been accelerated by the capabilities offered by disruptive technologies. A new generation of consumers places less emphasis on owning and more on sharing, bartering and renting goods. This shift in consumer behaviour, coupled with the capabilities of emerging technologies, has propelled an entirely new range of businesses – from shared car rides offered by companies like BlaBlaCar, to sharing accommodation on holiday via the likes of Airbnb.

Advancements in 3D printing technology are similarly paving the way for innovative manufacturing and production approaches. This enables the circular economy by disrupting the existing materials value chain and increasing the efficiency of the production process.

With the gradual reduction in price and improvements in quality, 3D printers could become commonplace in each home, similar to other household electronics. The option to acquire designs online and print our own products, from clothing to electronic parts and even food, could become routine. This sort of on-demand, hyper-personalised production could mean significant reductions in waste and increased efficiencies.

Governments and regulators are actively trying to support the circular economy. The European Parliament recently backed several laws that support the shift in EU policy towards a circular economy. According to the laws, by 2025, at least 55% of municipal waste should be recycled and 65% of packaging material will have to be recycled. In addition, the European Parliament has overwhelmingly backed a wide-ranging ban on single-use plastics. The benefits of a circular economy to the environment, climate and human health are widely recognised and accepted.

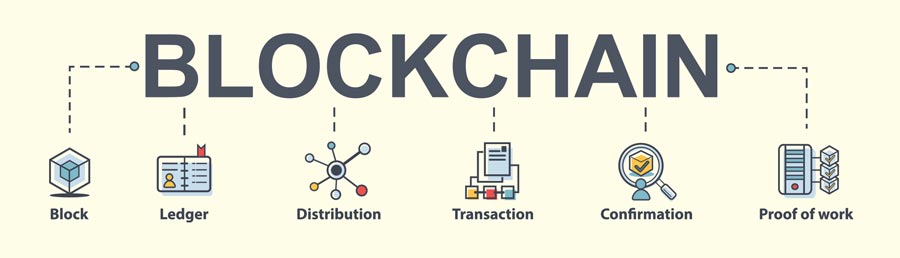

However, a majority of the regulatory environment, as well as economic incentives, still favour linear business practices. The current inability of supply chain stakeholders to track the provenance of materials, components and products throughout the value chain prevents assertion of their circularity – from extraction or creation, all the way through the many life cycle stages. In this respect, application of blockchain technology will have a transformative impact and enable a circular economy.

Essentially a distributed digital ledger system, blockchain was originally developed to record transactions for bitcoin, a well-known digital currency. Although digital currencies face scepticism and volatility in the global market, the underlying blockchain technology has grown in terms of credibility as more potential applications are developed across various industries.

Uses of blockchain technology

Supply chain management has emerged as one of the major use cases for blockchain technology, offering an efficient and almost fully tamper-proof way of tracking the cradle-to-cradle life cycle of goods. The blockchain translates chain of custody across the value chain into a distributed, immutable, digital trail that asserts the circularity of products.

For example, Bext360 combines several disruptive technologies, such as the Internet of Things, blockchain and artificial intelligence (AI), to create a fair and transparent coffee supply chain:

Since the Industrial Age, supply chains have followed a competitive business model that limits opportunities to create and leverage synergies. In addition, intermediaries continue to benefit from the lack of trust between supply chain stakeholders who are reluctant to share information and compete on costs.

In order to enable and engage in a circular economy, stakeholders need to be able to collect, process and share data within a trustworthy and secure environment. Blockchain technology, in combination with AI systems and the Internet of Things, could help establish a trust economy that lowers collusion between centralised parties, while also making them accountable.

Blockchain technology enables stakeholders to gather more knowledge on material cycles and processes throughout the value chain and to share data securely.

For instance, the startup Provenance intends to design a blockchain system that is able to track all used materials, including the dimensions of quality, quantity and ownership, over the whole supply chain in real-time. Basically, Provenance is trying to achieve a digital passport for any product, which enables consumers and producers to track the whole production process.

Foundation for success

Based on the current development trajectory of blockchain technology, it would be possible to establish a macro-economic incentive system that promotes transformation to a circular economy.

Within the linear economic system, raw materials are extracted from Nature, transformed into products and, finally, disposed back to Nature. Although the linear model could incorporate recycling, most of the components within this system have not been designed for reuse or regeneration, resulting in significant material degradation and accumulation of waste in the environment.

For example, the world today generates around 40 million tonnes of electronic waste each year. Even when recycled, a significant amount of electronic materials cannot be recovered. Conversely, the circular model aims to achieve a waste-free system – an economy which functions in loops and maintains the ecological value of materials over time.

With the application of blockchain technology, it will become possible to unambiguously identify a product’s inputs, including the quantity, quality and origin of materials. In addition, information regarding a product’s biological or technical components could be tracked on a blockchain. A blockchain-based system which is able to track product attributes would make it possible to adjust taxes according to the level of material degradation.

Ultimately, the application of blockchain technology could potentially enable transparency and traceability across end-to-end value chains, as well as crate a macro-economic incentive system that promotes the transformation to a circular economy.

Kamales Lardi

Digital Transformation Strategist

Lardi & Partner Consulting GmbH, Switzerland

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Techonology No Comments

The future of the palm oil industry has become uncertain in Europe. Last year, the European Parliament came close to a ban on palm oil imports in the region. The vote in favour of the revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) proposed to remove biofuels made from palm oil from the list of biofuels that counts towards the EU’s renewables target for 2021. The ramifications would have been significant, not only for palm methyl ester imports, but also for future hydro-treated vegetable oil (which uses palm oil as feedstock).

I have attended several biofuels conferences where the RED II and its potential impact on the industry were discussed in depth. As an objective external observer, I’ve found that the discussions tended to be emotionally charged, and based on perceived environmental and human rights violations by the industry.

Today, the dissemination of inaccurate information or ‘fake news’ is a challenge faced by many industries. Distorted information is able to directly shape public perception and even impact the direction of policy development across regions. As such, building an ecosystem of trust between palm oil producers, regulators, companies, environmentalists and end consumers will be pivotal in ensuring that the industry continues to thrive, particularly in the European market.

Social media and digital marketing channels have proven to be powerful and efficient tools for disseminating information and shaping public opinions. Over 50% of the European population actively uses social media channels. By launching strong promotions and campaigns focused on countering inaccurate information with facts on these channels, Malaysian palm oil could create a direct line of communication with the end consumer.

In addition, the application of blockchain technology could have a transformative impact on the palm oil industry by creating an auditable and traceable end-to-end supply chain. Imagine a customer in a store looking to buy a bottle of shampoo that has a ‘deforestation-free’ label on it. With a simple mobile app, the customer is able to see where the palm oil used in the shampoo originates, including a video that shows the plantation where the fresh fruit bunches and oil palm tree were grown, and how exactly the palm oil ended up in the shampoo production. These palm kernels have been tracked across the globe with blockchain technology.

Blockchain is essentially a distributed digital ledger system. It was originally developed to record transactions for bitcoin, a well-known digital currency. Although digital currencies face scepticism in the global market, the underlying blockchain technology has grown in terms of credibility as more potential applications across various industries are developed.

Supply chain management has emerged as a legitimate use case for blockchain technology, tracking raw materials through production and allowing everyone in the supply chain to know where a shipment is located.

So, what makes blockchain unique? The digital ledger records transactions in a series of blocks, and exists as multiple copies spread over multiple computers. The ledger is secure because each new block of transaction is linked back to the previous block in a way that makes tampering practically impossible.

Each time new data is added, all copies of the ledger are updated and validated simultaneously, while previous data records cannot be altered. This decentralised structure means that no single person or group has full control over the data.

Blockchain technology is applicable in any business or industry, to record transactions of almost anything of value. Emerging applications for blockchain technology are geared to improve business operations in numerous ways, including supply chain transparency and credibility for all kinds of products.

Last year, for example, shipping conglomerate Maersk deployed a blockchain-based electronic shipping system to digitise supply chains and track international cargo in real time. The advantage of blockchain technology is the immutable records of data and the trust people can have in it.

Infallible validation system

In the palm oil industry, the use of blockchain technology combined with mobile apps and other related technology, such as QR Codes, RFID tags and Internet-connected sensors, could result in near-perfect sustainability records.

Malaysia is currently working to certify the sustainability of its palm oil through a mandatory programme for the entire production and supply chain by Jan 1, 2020. The Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil standard is aimed at offsetting negative perceptions about the industry and `fake news’ that has been misleading consumers, particularly in Europe.

At its core, existing certification schemes still depend on some form of manual Chain of Custody systems. In other words, doubts about the validity of the certification schemes may be related to the dependency on human intervention and paper-based processes that may be subject to errors or malicious activities.

The application of blockchain technology in the Malaysian palm oil industry has the potential to alleviate any doubts, by creating greater transparency and auditability across the entire supply chain. Instead of having to trust the elements of a certification process where doubt may be cast due to paper-based or human error, blockchain technology offers an infallible validation system that secures trust.

This not only provides an unprecedented level of transparency, but also contributes to protecting the working conditions and legal employment of field workers, and gives plantations rich data on crop harvesting.

With the use of geolocation features, farmers, governments, certification authorities and producers can maintain digital inventories of the plantations, and implement sustainable land usage planning policy. Additionally, use of sensor technology could minimise spoilage by monitoring temperature and humidity during processing, storage and transport, and integrating this data on the blockchain.

The oil palm industry in Southeast Asia is a saving grace for many small farming families. In addition, growing oil palm requires less land and results in higher yield than other vegetable oil crops. In May 2018, a study by researchers at Imperial College London revealed some of the challenges faced by companies in guaranteeing products labelled as ‘deforestation-free’.

The lead author of the study, Joss Lyons-White of the Grantham Institute – Climate Change and the Environment and the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial said: ‘Deforestation-free palm oil is possible, but our study found it is very challenging for companies to guarantee at present.

‘For example, supply chains are so complex that tracing palm oil back to source is very difficult – lots of trade may occur between different parties before manufacturing, where the palm oil is used in many different products for different purposes. This makes it hard to know exactly where the original oil was from – and whether it was linked to deforestation or not. However, simply banning palm oil is unlikely to be the answer. Instead, we need to find ways to ensure commitments can be implemented more effectively.’

Establishing sustainable practices in the palm oil industry needs to strike a balance between several aspects – human rights, environmental impact and economic contributions. The application of blockchain technology could be a solution that would enable Malaysia to utilise the existing palm oil infrastructure and guarantee that sustainable practices are implemented and continuously tracked.

Kamales Lardi

Digital Transformation Strategist

Lardi & Partner Consulting GmbH

Switzerland

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Markets No Comments

Uzbekistan is Central Asia’s biggest economy and a trade hub for the region. The country has a land border stretching over 6,893km, which is shared with Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

Uzbekistan is home to more than 32 million people, with about 40% of them based in urban areas in Tashkent, Navoi and Samarkand. Population growth has been steady at an annual average of 1.5%. At this rate, the population could exceed 35 million in 2025 and 41 million in 2050.

From Independence in 1991, the government led by President Islam Karimov had controlled the economy, especially sectors like banking services and the production of oil and gas, minerals and food products. Despite entry and operational barriers, the economy grew respectably. However, it failed to inspire the confidence of foreign investors and big corporations.

Many feared that, after the death of President Karimov in September 2016, the country would descend into chaos. But the new president, Shavkat Mirziyaev, who had been the Prime Minister for 13 years, adopted a balanced policy on both the foreign and domestic fronts. He has introduced a wide range of economic reforms since 2017:

Source: The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics

Source: The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics

Source: The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics

Overall, the improvements have had a positive effect on the economy and restored investor confidence. Since January 2017, more than 32,000 new small and medium business entities have been registered; of these, about 27% are engaged in industrial production and manufacturing. Uzbekistan’s overall trade showed an increase of 7.7% in 2017, compared to 2016.

Oils and fats market

Uzbekistan is emerging as the leading consumer of oils and fats in the Central Asian Region. Total consumption currently stands at about 556,000 tonnes, of which 52% is met by locally produced oils and fats.

The edible oils industry is dominated by domestic cotton seed oil and imported sunflower oil from Russia and neighbouring countries. Cotton seed is the largest oilseed crop in Uzbekistan, with a share of about 50% of total consumption of oils and fats. However, production is declining due to a government policy to shift the focus away from the textile industry. The reduction in the supply of cotton seed oil and increase in overall consumption will widen the gap between supply and demand – this will have to be bridged by imports.

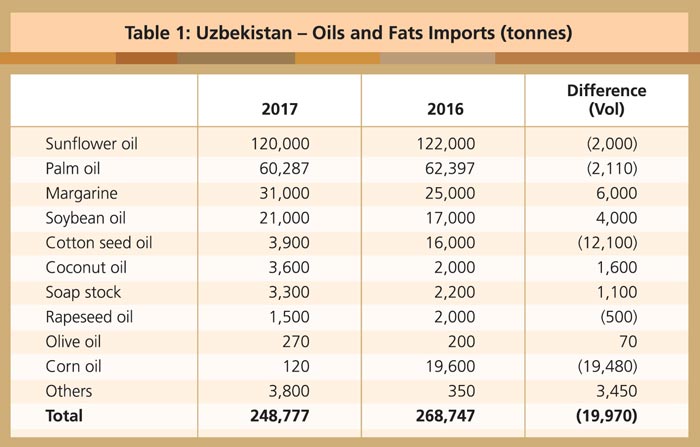

Edible oil imports in 2017 registered 248,777 tonnes (Table 1), or 7.5% lower compared to 2016. The decline was mainly due to the currency rate adjustment in September 2017, which resulted in devaluation of more than 90%. This increased the cost of imports out of proportion and many contracts were cancelled. After the initial shock, the import market settled in the following months and picked up from January 2018.

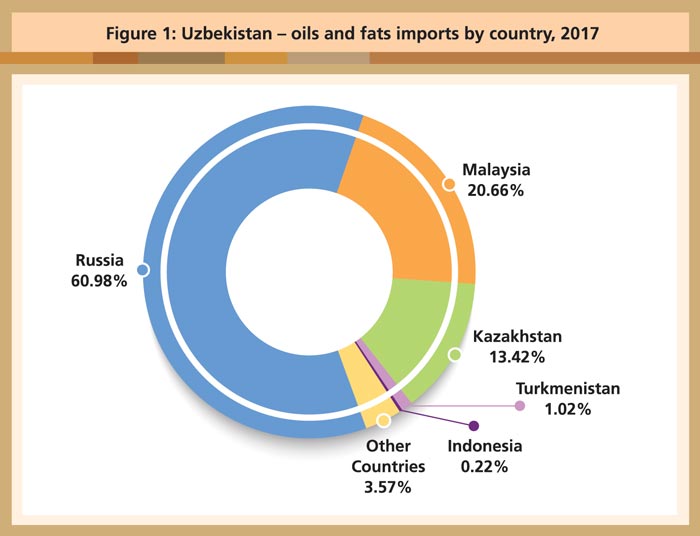

Imports are dominated by sunflower oil which accounts for 48% of the total volume. Primarily used as a premium cooking oil, it is imported from Russia, Kazakhstan and other CIS countries. Palm oil is the second-largest import and is fast becoming a key ingredient in the confectionery and food industries.

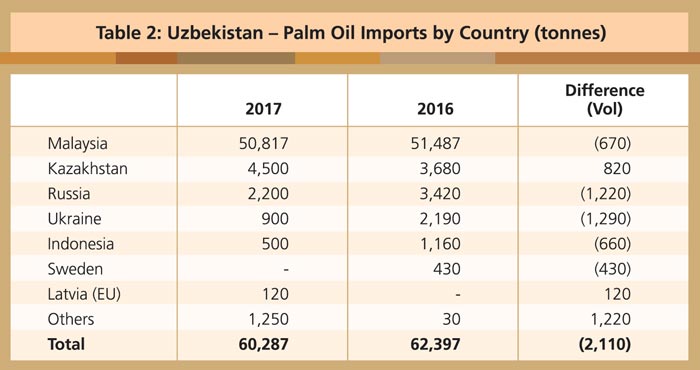

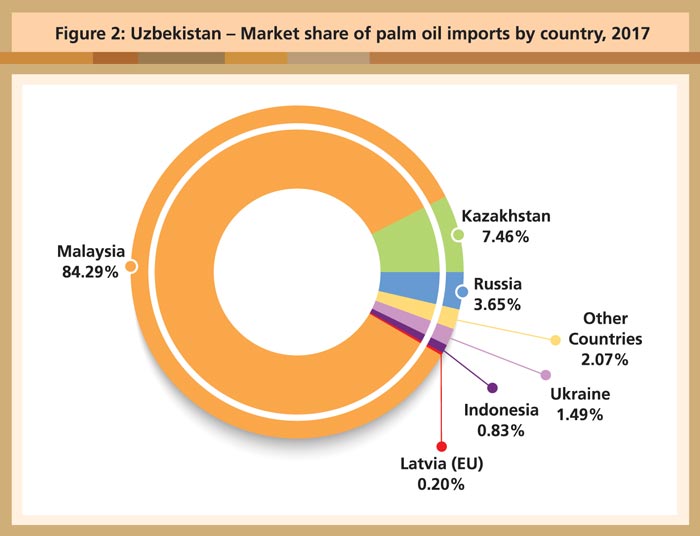

Uzbekistan imports most of its oils and fats from the neighbouring CIS countries as they have open borders and a preferred duty structure. Malaysia is the only country which has managed to secure a sizeable market share in this double landlocked country. In 2017, Malaysia held a market share of 84.3% in palm oil imports (Figure 2), and 21% of total oils and fats imports.

Source: The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics

Prospects for palm oil

Palm oil has become an important ingredient in Uzbekistan’s food industry, with its use and consumption having risen consistently. The food industry has registered double-digit growth over the past three years and this is expected to continue. Margarine, confectionery and ice cream are the main industries that use palm oil and its various fractions.

Palm oil distribution has been controlled by several importers who obtain supply from Malaysia, Ukraine and Russia, and then distribute it locally. Most industries have not bought palm oil directly, mainly due to foreign currency restrictions up to 2017. However, there is now keen interest in buying direct from suppliers in order to obtain a better price, consistent quality and after-sales support.

Until recently, the import duty on palm oil had been higher if supply was obtained from Malaysia and Indonesia, compared to the CIS countries. A significant volume of imports had therefore shifted to suppliers from Ukraine and Russia.

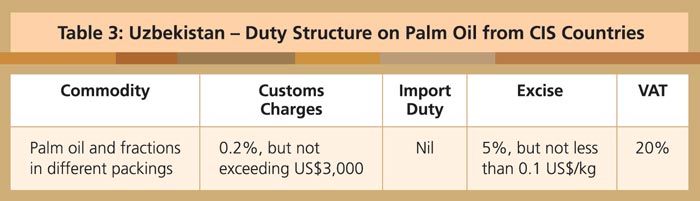

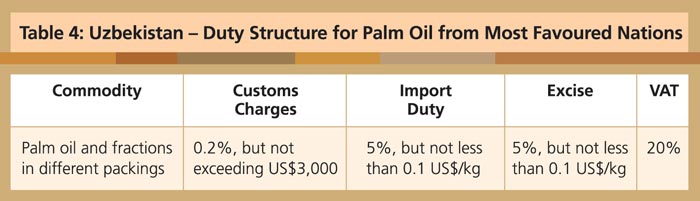

Oils and fats have been subjected to very high import duty and taxes. The total tariff on oils and fats imported from CIS countries came up to 26%, compared to 31% from Malaysia and Indonesia and other countries with Most Favoured Nations status. Under the reforms, however, the government pledged to reduce the import duty and VAT on imports including palm oil, and to provide a level playing field for all countries.

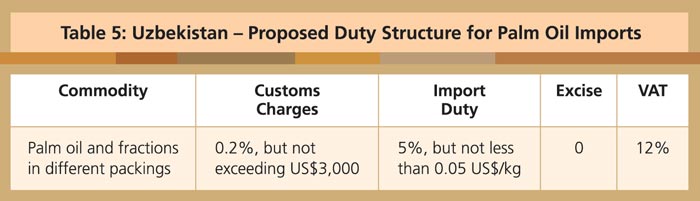

The government’s decision to reduce the duty and tariffs from 31% to 18% has been applauded, as this will not only bring down retail prices but will also enable industries to step up their production capacity.

This duty structure is due to take effect from January 2019, and is expected to boost palm oil supply from Malaysia, while encouraging industry members to import directly. The potential for growth in the import of palm oil has never been better.

Faisal Iqbal

MPOC Pakistan

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Environment No Comments

Palm oil production has often been blamed for deforestation in Southeast Asia. However, this does not do any justice to ongoing conservation efforts in Malaysia by both the authorities and non-governmental entities, as well as regional and international organisations.

Read more »By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Comment No Comments

The World Health Organisation (WHO), in a recent article, turned its sights on the palm oil sector. The article is riddled with errors, omissions, assumptions and other evidence of bias. The fact that such bias exists is a major issue, but this is not the only problem.

The WHO takes issue with the palm oil industry for making use of ‘lobbying to the detriment of scientific evidence’. In doing so, the WHO itself regurgitates the talking points of anti-palm oil lobbyists, while ignoring voluminous scientific evidence on the benefits of palm oil. This lack of self-awareness is painful.

Are the WHO’s claims substantiated? Let’s start by looking at the issue of poverty.

The authors complain that the palm oil sector relies on ‘poverty alleviation arguments’. In this, the WHO is correct. Oil palm cultivation has lifted millions out of poverty by providing a regular income for small farmers and rural communities. It has helped Africans, Asians and others build better, healthier lives for themselves and their children.

Is the WHO saying that this is a bad thing? If so, it needs reminding that poverty is one of the most significant drivers of poor health. As the World Bank notes: ‘Poverty is a major cause of ill health and a barrier to accessing health care.’

Palm oil offers a unique dual benefit to producers and consumers, many of whom are based in the developing world. The producers include small farmers who can make a living and attain better quality of life. Consumers – including the poor – receive key nutrients including Vitamin E tocotrienols and tocopherols from consuming palm oil. In both instances, the main benefit is better health.

Lifting millions of people out of poverty has done more to improve global health than the WHO could visualise. But perhaps the real criticism is that palm oil producing countries ‘talk too much’ about poverty alleviation. In this respect, the Malaysian palm oil sector is guilty as charged.

For years, Malaysia has provided data, studies and articles that highlighted how the country has built successful rural communities and derived economic growth based on oil palm cultivation. Malaysia was able to reduce poverty from 50% to less than 5% within a few decades. As a result, its model of oil palm cultivation is being studied and replicated in many poor countries.

Surely, this should be celebrated by the WHO? Sharing knowledge on proven poverty alleviation efforts leads to better health conditions in poor countries. Instead, the WHO chooses to fall back on wearisome attacks on palm oil.

Repeat of allegations

The WHO next criticises palm oil in the context of trans fats. Just to be clear, trans fats have been universally condemned as deleterious to human health. In its natural state, palm oil has zero trans fats, while serving the required functions in food preparation. Again, the simplest answer is the correct one: this is a clear win for human health.

The WHO article ignores this positive as well. Instead, it asserts that ‘the palm oil industry may benefit from increased sales’. Are the authors claiming they would prefer lower health outcomes or a reintroduction of trans fats into the food supply chain?

The article moves on to adopt a copy-paste version of extremist NGO attacks on palm oil, even though these have been repeatedly debunked. If the authors had done basic research, they could have easily discovered the facts:

The article is at least honest about its bias. Throughout, it quotes anti-palm oil rhetoric approvingly and at length, despite the absence of scientific verification. At the same time, it condemns published research with even the smallest link to the palm oil sector. This is a classic case of judgment based not on evidence, but on pre-existing prejudice (‘NGOs good; palm oil bad’).

Any balanced evaluation would conclude that the oil palm is a valuable crop. It uses less land (meaning more can be kept for conservation); fewer pesticides (which the WHO has acknowledged is a good thing); and less fertiliser.

The article compares scientific research on palm oil to studies sponsored by alcohol and tobacco companies to promote their products. When it is established, for example, that the tocotrientols in red palm oil provide essential vitamins to nutrient-deprived communities across the developing world, it is bizarre that the WHO lazily compares this to cigarettes or liquor. This would be laughable if it were not so irresponsible.

But if there is one saving grace, it is this: The WHO authors admit that ‘we need to better understand … palm oil products’. Yes, it is clear that they do.

Faces of Palm Oil

This is an edited version of a blog-post. Faces of Palm Oil is a joint project of the National Association of Small Holders, Federal Land Development Authority, Dayak Oil Palm Planters Association, Sarawak Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority and MPOC. It advocates on behalf of Malaysian small farmers.

By gofb-adm on Sunday, March 31st, 2019 in Issue 1 - 2019, Comment No Comments

The world’s population stands at 7.6 billion today and is expected to reach nine billion by 2050. At the same time, the availability of arable land remains roughly the same. In fact, arable land is becoming scarcer, relative to the number of people who have to be fed.

According to UN figures, an additional 2.7-4.9 million ha of cropland will be required every year to feed the world’s population. But climate change, urban development and rural population migration affect agriculture directly.

Every year, between one million and two million ha of land become unsuitable for cultivation due to land degradation. Efforts to rehabilitate such land are extremely expensive. Therefore, more innovative and efficient agricultural land use policies are needed to step up food supply.

The first fact to recognise when considering food security is that the world is not homogeneous. Global food production is not evenly distributed among all countries.

Countries with a conducive climate and human capacity have surplus food production and will not encounter food security issues. Those that are less well-endowed will encounter food security issues. Very often, they are countries with large populations. This, clearly, is a potential cause of significant economic and social instability.

By 2050, an additional 35 million tonnes of oils and fats will be needed every year around the world. This posts a major challenge in that large areas of land will be required to meet the additional demand.

In order to produce 35 million tonnes of oils and fats, 88 million ha of land would be required for soybean cultivation or 58 million ha for sunflower. In contrast, only nine million ha of oil palm would be needed to produce the same volume of food – the actual area may be smaller due to productivity improvements over time.

Realising this, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation has recognised the importance of planting oil palm for food security, especially in developing countries. Although oil palm occupies only 0.3% of total agricultural land, the crop contributes more than 30% of the world’s supply of oils and fats.

Sustainability certification

World-leading efficiency on its own has not been sufficient to lead palm oil into the good graces of decision-makers. Consistent negative campaigns about palm oil’s alleged environmental impact have damaged its image and forced the industry to respond to prove its sustainability credentials.

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) is today the most widely accepted sustainability certification scheme for palm oil, particularly for use in food and chemicals. Indeed, the RSPO has made significant progress and impact in promoting the production, supply and use of sustainable palm oil.

However, there are signs that the RSPO is increasingly alienating oil palm growers; they have become disillusioned by the continuously shifting sustainability criteria or application of these during audits.

Let’s look at the statistics of membership. In 2008, four years after the RSPO’s formation, member-growers made up 19.1% of membership; 10 years later, a mere 4.4% of the total membership comprised member-growers. These statistics showing a gross under-representation of growers should be a wake-up call for the RSPO and the advocates for sustainable palm oil.

Growers are the ones who bear the brunt of the hard work, undergoing regular audits involving almost 100 criteria. They form the source of the palm oil supply chain on which the very existence of the RSPO depends. If the goose that lays the golden eggs disappears or shrinks substantially, it would be meaningless for the remaining members – food companies, retailers and NGOs among other stakeholders – to talk about promoting the use of sustainable palm oil.

The RSPO’s core objective is to ‘promote’ the production, supply and use of sustainable palm oil. ‘Promote’ means ‘encourage’ and has an underlying tone of voluntary effort and incentives.

However, membership for growers has turned into an avalanche of complaints against their production practices, and hardly any complaint against other member-groups. With this – coupled with the less than 50% uptake of the certified production volume as well as the fast-declining RSPO premium – it is not surprising that expansion of the growers’ membership is so slow and that under-representation of member-growers is so stark.

Due to the stringent RSPO criteria and significant certification costs, there is a real need for other schemes that are cheaper, less complex and more broad-based. The Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil standard, for example, is a much-welcomed certification scheme which is backed by the government and can be adopted by a much wider spectrum of growers, including smallholders.

Negative activism

The era of the Internet and social media has proved a boon to environmental NGOs from western countries, as they are able to reach out to netizens around the world and garner a strong following to promote their causes. Palm oil has become a favourite target of these NGOs.

Armed with academic knowledge gained from western institutions, as well as information extracted from studies based on dubious science, activists who are mostly in their 20s and 30s have a tendency to exert their opinions on oil palm growers who have spent many years practising their trade.

The NGOs are relatively small in size, with manpower as low as five for the smallest to perhaps a few hundred for the bigger ones. However, with clever use of social media and shrewd propaganda tactics, they are able to sway consumer perception. They also dictate to oil palm grower communities, which total several million people, on how environmental conservation should be carried out in less developed countries.

It is acknowledged that activist groups play an important role by providing alternative views and serving as a check-and-balance on matters of interest. However, in many instances, their approach to resolving issues could be less confrontational, more sympathetic and more collaborative. The fact is that growers are the ones who do the tough job of ensuring that oil palm is grown in an economically, socially and environmentally sustainable manner.

The campaigns by activist groups in restricting oil palm planting have been effective, as seen from the much slower expansion of the planted area over the last few years. The Indonesian government has extended a moratorium on approving new land for oil palm planting. Recently, the Malaysian government also announced a restriction on oil palm expansion.

These are good short-term measures that allow proper environmental protection to be implemented effectively on the ground, and to moderate the growth of palm oil supply in the global vegetable oil market.

However, a proper balance should be struck to avoid other socio-economic problems such as food insecurity, food price inflation and an imbalance in rural development from surfacing in the longer term.

Dato’ Lee Yeow Chor,

Chairman, MPOC

This is an edited version of an article published in the Star on Jan 7.