For Malaysia's palm oil sector

October, 2018 in Issue 3 - 2018, Comment

The oil palm industry in Malaysia is at a tipping point. It is faced with multi-dimensional challenges that need action and long-term vision. The exponential growth in the cultivation of oil palm has helped feed the world’s growing demand for food, feed, fuel and fibre, and brought about many economic benefits.

However, the success story of the oil palm has raised its international profile, resulting in heightened public scrutiny and criticism. Detractors claim that the success of oil palm has come at a huge cost in terms of the environmental and social damage. Oil palm cultivation has been associated with problems linked to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, human rights breaches, and land and labour issues. Palm oil also has to contend with quality issues like process contaminants.

In addition to these challenges, climate change resulting in fluctuation of precipitation and increasing frequency of floods and droughts adds another layer of complexity. Tackling the complex environmental, social and technical issues in the palm oil supply chain requires transformation of the entire industry. Transformation is contingent upon concerted action by all stakeholders and committed work on the ground.

The EU challenge

On account of the perceived negative impacts of the oil palm, there have been repeated threats of boycott of palm oil. In April 2017, the European Union (EU) passed a resolution banning the use of palm oil in various products including palm oil biofuels after 2020. The self-interest of the European agricultural sector lies at the core of the ban, as palm oil competes with European-grown rapeseed as a feedstock.

In August 2017, the EU launched the ‘International Palm Oil Free Certification Accreditation Programme’ in efforts to discourage the use of palm oil in food products. Fortunately the EU recently softened its stand and the European Parliament plans to retract its demand for post-2020 restrictions on palm oil, proposing instead to cap the use of biofuels from food or feed crops.

Such actions would adversely affect Malaysia’s balance of trade, given the central importance of palm oil as a commodity export. Simply banning or capping the use of palm oil is not the answer. It is more important to ensure commitments to sustainability are implemented more effectively.

The industry cannot be in denial mode. It must acknowledge existing problems and forge a positive narrative for change. It needs to seriously change and adopt stringent standards. There is an urgent need for engagement with stakeholders and the international public to show the obtuseness of proposed bans against palm oil. Emotive outbursts among concerned European consumers need to be offset by a more mature response that acknowledges the concerns, but also explains the benefits and opportunities.

Increasing environmental activism and actions like those of the EU articulate the need for sustainable practice. The financial payoff of a proactive sustainability strategy can be substantial as it will improve international competitiveness, social and environmental performance, and increased profitability.

A commitment to sustainability will catalyse closer examination of production processes, resulting in improved product designs, product quality, production efficiency and yields in tandem with environmental improvements. This would increase global exports over the longer term. It is thus important to have a credible framework for sustainability.

Mechanisation the way forward

The oil palm industry is highly labour-intensive. All its operations, from planting to processing, are highly dependent on manual labour and this is especially so in the plantation sector. Although this creates job opportunities, it does not appeal to local workers because of the 3D perception – that the work is dangerous, demeaning and difficult.

Instead, we have become reliant on foreign workers. As at May last year, there is an estimated 427,000 workers in the Malaysian oil palm plantation sector; about 77% are foreign workers employed largely in high labour demand operations, especially crop harvesting and replanting.

Over-dependence on foreign workers creates risk to the oil palm industry. This is especially so when there is a policy change in their home country or they are no longer interested in working in Malaysia. Competition from Indonesia, which has larger land and labour reserves, emphasises the importance of reducing dependence on foreign workers. Any disruption to the labour force would have a significant impact on the industry.

The new Malaysian government had set the minimum wage at RM1,500 in its election manifesto, and the new minimum wage for the private sector is undergoing a review process. The proposed minimum wage will still hurt the oil palm industry as it will significantly increase the cost of production. It was estimated that it would translate into an additional cost of RM185 per tonne of crude palm oil.

Mechanisation of the oil palm plantation sector is thus not a luxury; it is an imperative. It cuts dependence on foreign labour and costs, including foreign exchange losses as a significant portion of wages are repatriated out of the country. Sustainability and competitiveness of Malaysia’s oil palm industry hinges on extensive mechanisation in all the field operations.

Biotechnology revolution

Biotechnology has revolutionised agriculture and transformed the global economy into a bio-based economy. While we develop tools to fit the oil palm, genomics is opening new horizons for breeding and developing palms to fit the tools available. With the sharing of the genome sequence by MPOB, industry is directing efforts on genomic selection for short palms to mitigate harvesting problems associated with tall palms. Planting virescens palms – the fruits of which have a distinct colour change on ripening – will also improve harvesting standards. The discovery of the virescens gene by MPOB allows for the selection of virescens at the seed or nursery stage.

Sustainability entails efficiency along the entire supply chain. High-yielding planting material is a critical component of sustainable oil palm production. This is especially so since the oil palm is a perennial crop with a replanting cycle of 20-25 years. The importance of eliminating dura and pisifera contamination in nurseries and subsequent commercial plantings cannot be over-emphasised. Dura and pisifera palms yield 30% and 100% less oil respectively than tenera palms and, if not removed early, will be out in the field for the 25-year duration of their economic life span. Getting it wrong at the upstream affects the entire value chain.

Although most of industry insists that the level of non-tenera contamination is less than 2%, the discovery of the SHELL gene by MPOB and subsequent availability of a SHELL gene assay for identifying tenera, dura and pisifera have unequivocally confirmed that this is not the case; the non-tenera contamination in Malaysia is around 10% across all sectors and not just smallholdings.

Missed opportunities

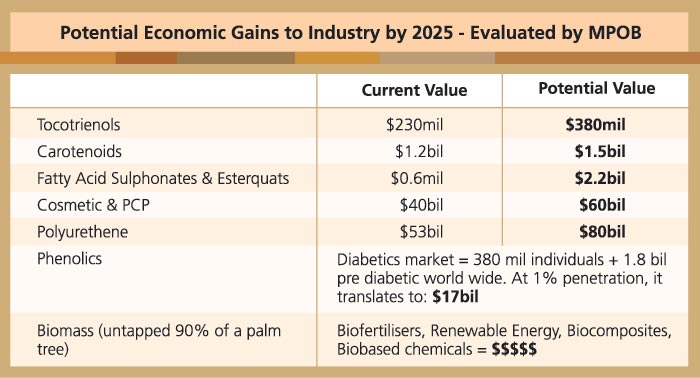

Valorisation of palm oil mill by-products, an example of extraction of natural products from agro- industrial waste, is attractive from both the socio-environmental and economic aspects. The extraction of phenolics from the aqueous waste stream of palm oil milling is one example which integrates health with socio-environmental and economic aspects. It is heartening that this innovative technology developed by MPOB caught the attention of Mexican investors; the world’s first commercial oil palm phenolics production plant is currently under construction in Mexico.

The absence of buy-in of this technology by players in the Malaysian oil palm industry shows the risk averseness of the industry to new home-grown technologies and reluctance to do things differently. In general, the downstream value addition technologies developed locally by MPOB and others is an area that the industry has failed to fully capitalise on and may be a missed opportunity. Income growth from oil palm can mainly come from price increase or downstream value addition. While technology initiatives continue to intensify, they are often thwarted by a lack of adoption rather than the merits of the technology. Change is a significant hurdle.

Source: MPOB

There is also the need for the government to review current tax incentives for pioneer manufacturers to register patents because the process to protect their intellectual property (IP) rights can be time consuming and costly. This is perhaps one of the key reasons why a great deal of research and innovation is not commercialised within Malaysia.

There is no specific tax incentive in Malaysia for registering IP protection on a worldwide basis. There is also no government funding for commercialisation of research in pilot testing and field/clinical trials. It is a long and winding process to bring an idea to the drawing board and eventually commercialise it. This is costly because experimentation involves heavy upfront investments.

In summary, major transformations leveraging scientific knowledge and policy changes are imperative along the entire supply chain of the oil palm industry to meet the multiple challenges. The volatility of the market and tariff and non-tariff barriers emphasise the fact that just producing palm oil as a commodity is no longer enough.

Value addition through innovative downstream activities is imperative. Continuous improvement and innovation are essential, as the market becomes more complex and competitive with escalation of market access barriers, policy barriers, and technical and non-technical barriers. Sustainable development calls for long-term actions and requires ownership, capacity and consensus.

We are way off the RM178 billion revenue targeted by 2020 under the National Key Economic Area for the oil palm industry. Government-initiated total restructuring of the industry may be necessary in order to realise the economic potential and for it to be the global stalwart for the food, feed, fibre and fuel industries. Therefore, ‘business as usual’ is NOT an option anymore.

M R Chandran

Director & Past National Chairman,

The Incorporated Society of Planters

This is an abridged version of the Keynote Address presented at the 14th ISP National Seminar, held from July 16-17 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.