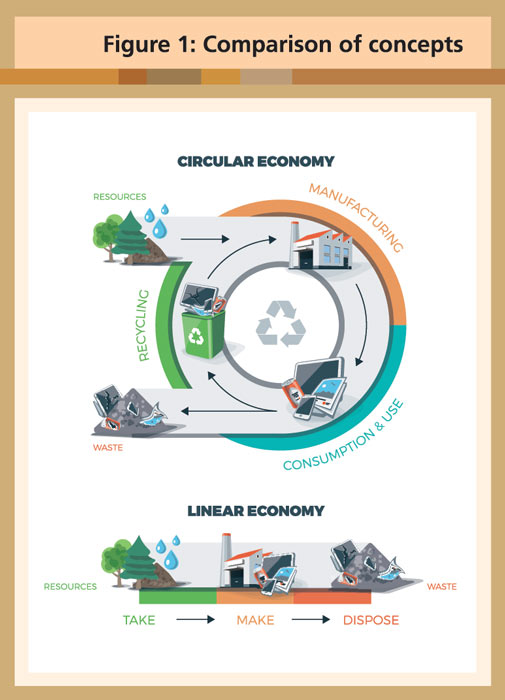

The circular economy (CE) – as opposed to a linear one – describes a regenerative system in which resource use and waste production, emissions and energy waste are minimised by slowing, reducing and closing the energy and material cycles.

This can be achieved through durable design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing and recycling. In practice, recycling – i.e. bringing waste products back into the cycle as secondary raw materials – plays the key role in the CE. This is of particular importance to the palm oil industry.

The linear economy, also known as the ‘throwaway economy’, is the current dominant principle of industrial production. A large part of the raw materials used is deposited or burned according to the life cycle of the products. Only a small proportion is reused.

Expressed as a simple formula, the antagonism between the two concepts is described as take-make-dispose (linear model) vs reduce-reuse-recycle (circular model).

Source: © petovarga/fotolia.com

However, it emerges that there are different schools of thought on the CE. They go by names like cradle-to-cradle, performance economy, biomimicry, industrial ecology or natural capitalism. What all of them have in common, though, is that they aim to:

The CE concept has gained traction in recent years with policy makers and business operators alike. While some researchers caution that it may be just another passing fad, there is no mistaking that the underlying assumptions are here to stay.

The assumptions have been around since the beginning of human economic activity. For instance, traditional agriculture has always been circular. The production energy in the form of human or animal muscle power was fed directly from the cultivated area. Waste like excretions or kitchen litter, and production residues such as straw or ashes from clearing land with fire, were returned directly to production.

Business entities and governments are therefore well advised to take a closer look at the CE. Some countries have already done so. China has had a CE Promotion Law since 2009. The indicator system used to measure its CE is an altered version of the EU´s material flow analysis, which the Chinese have studied extensively and adapted to their own needs.

The European Commission (EC), in its efforts to make Europe’s economy more sustainable, adopted a new set of measures in January 2018, called the CE package. It includes actions on plastics, waste legislation, critical raw materials and a monitoring framework. The EC’s work on the CE is influenced by the International Resource Panel established in 2007 by the United Nations Environment Programme.

In October 2018, the EC’s Directorate General for the Environment organised a CE Mission to Indonesia. This was to ‘build bridges between European institutions, NGOs and companies, as well as the relevant stakeholders in Indonesia interested in the opportunities that the transition to the circular economy brings’. With that, the CE reached the world’s biggest producer of palm oil.

There is not only an environmental case to be made for the CE, but an economic one as well. As British weekly The Economist writes: ‘Environmental problems, such as biodiversity loss, water, air, and soil pollution, resource depletion and excessive land use are increasingly jeopardising the earth’s life-support systems.’

The Economist also observes that more governments have come to realise that investing in sustainability and the CE, in fact, saves money. Take the example of public health: avoiding respiratory diseases by taking measures to improve air quality in cities may turn out cheaper than treating those affected.

The same is true at the corporate level. An increasing number of companies, investment funds and banks, especially in Europe, now accepts that the CE is not a costly fad or simply a way to satisfy the green lobby. Rather, it will improve the bottom line in the long run.

Optimism for palm oil in the CE

The production of palm oil results in enormous quantities of secondary products – palm oil mill effluent (POME), empty fruit bunches (EFB), palm oil mill sludge, oil palm fronds, oil palm trunks, decanter cake, seed shells and palm pressed fibres. The biomass has massive economic potential:

However, to make a financially feasible shift towards the CE is tricky. A vicious cycle must be overcome. Recycled materials must compete with virgin ones. A successful recycling industry must operate on scale. This would encourage investments in technology and efficiency to make recycling more competitive, and to provide a supply steady enough to create demand.

In a look at why businesses are trying to reduce, reuse and recycle, The Economist points out: ‘Things such as glass, paper and many metals have broken out of this vicious circle, typically once economies spewed out enough of them to make it worthwhile to recycle. Reprocessing technology had often been around for a while – paper was being recycled in the 19th century – but greater availability of source materials encouraged efficiencies. That in turn spurred demand for these materials and itself encouraged further improvements in recovery. In other words, a vicious cycle turned virtuous.’

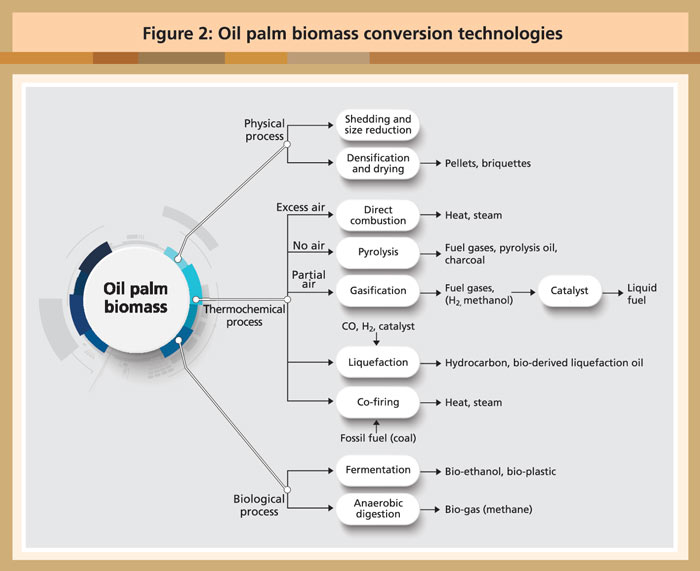

Given the abundance of recyclable biomass in the palm oil industry, plus the competitiveness of the resulting products, there is ample reason to be optimistic about the potential of the CE approach. There are many different use scenarios on the plantation and at the mill (Figure 2).

Source: Shuit, SH et al.; Oil palm biomass as a sustainable energy source: A Malaysian case study, in Energy 34(2009)

The expansion of palm oil production partly caused the tightening of environmental legislation screws in Europe. The next few years will show if this proves to be a happy coincidence for the palm oil industry after all.

Europe is decarbonising its economy. This means phasing out not only fossil fuels in the long run, but also moving away from first-generation biofuels. Electrical power will not be able to fill the gap, given the scarcity of the natural resources needed to build batteries and the environmental havoc caused by mining them.

Enter second-generation biofuels. European broker Greenea´s vision for the immediate future of biofuels is this:

Malaysia is in the midst of coming on board. Reports indicate that the Malaysian biogas market aims to equip all 447 palm oil mills in the country with biogas plants by 2020. That would be a momentous step forward. And who knows what other opportunities technological innovation might bring?

Just to give an example, the Malaysian Palm Oil Board has been experimenting with microwaves to sterilise fresh fruit bunches instead of using steam. On the one hand, this would eliminate POME (and the chance to capture methane); on the other, it would reduce the water content in empty fruit bunches, thus improving their suitability for use as fuel.

Prospects for palm oil in the energy sector seem promising. Rating agency Fitch has noted that incentives for advanced biofuels under the 2021-30 phase of the EU Renewable Energy Directive would boost demand for recycled palm oil and palm oil waste products, including mill effluent and EFB.

Other opportunities like the collection of used cooking oil (UCO) have not reached the mainstream of the palm oil industry. The European Union already imports UCO at scale. For the first eight months of 2018 alone, industry analyst Argus Media reports imports of more than 235,000 tonnes, four times the 2017 total. Similar developments are observable for biodiesel made from UCO.

Against this backdrop, the time has come for the Malaysian palm oil industry to think harder about the products it could sell. Investment in efficient processes will pay off not only in the production of palm oil, but also in processing the associated biomass.

MPOC Brussels